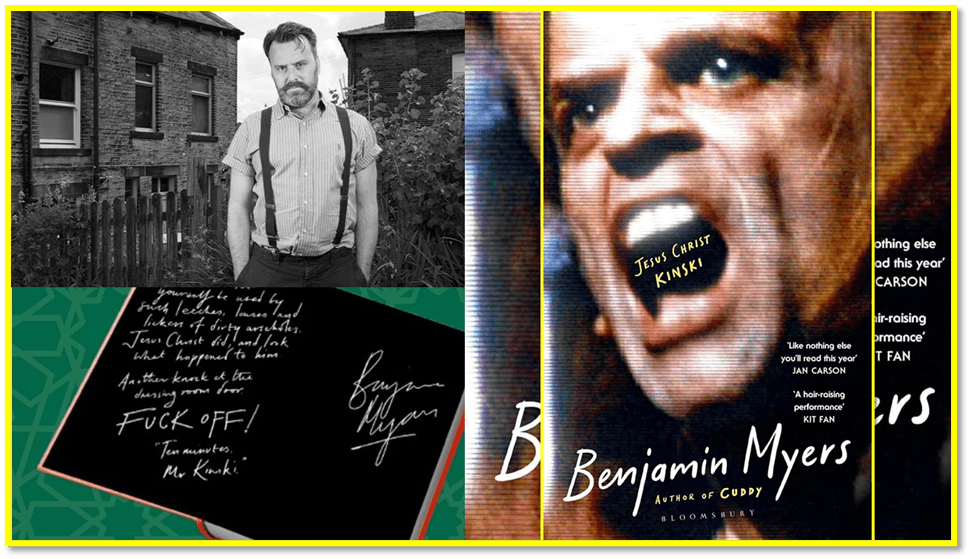

Making your mark from the offset: the fallacy of control. This blog is a reflection on Benjamin Myers’ new work, ‘Jesus Christ Kinski: A Novel about a Film about a Performance about Jesus‘.

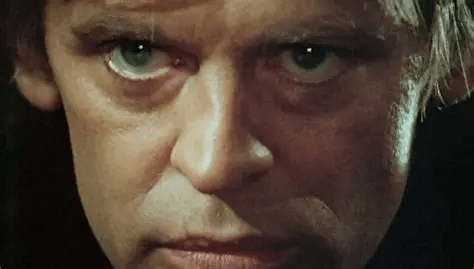

A quiet man reflects on a loud one, whose mouth is full of hubristic pretension and loudly scored swear words. How does each make their first impression?

There are endless tips available online on the ‘first impression you should ‘want to give’ people when you first meet them, as you debut in an interview, on stage in a new role, give a speech about some item that ought to matter very much, or write a new book. They whole talk about making a good first impression and sometimes cite the evidence from experimental cognitive psychology for the importance of primacy effects in making one’s contribution memorable. But let’s linger on the semantics on the word ‘impression’ itself, which relates to the temporary (or permanent) mark left on a receptive surface – and the receptivity of the surface matters a lot – by the imposition of external pressure. As I squeeze your hand, or any other part of your body, your impression of my touch will relate to the physical interaction of the skin and its underlying structures and the energy that determines the pressure made on those things. A smack from the hand on a child’s bottom by its parent, a kiss on or between the lips or even the ink staining cut under the first layers of the skin by a tattoo needle can leave a mark – it will be more or less permanent dependent of the effect of stains that are applied at the same time as the pressure, either by the internal substances of the body impressed upon or dyes (their colour and potential to permanence, co-applied with the thing making the impression.

After a fall or a fight where a blow has been received we worry about whether the impact of the impression will leave a mark as the soft skin remoulds into its original form, with or without bruising, or contamination by things accompanying the blow. Abusive parents worry more than others and not just because the child might be damaged by violence but because that violence having occurred will be readable on the skin by a safeguarding professional. Tattoos gained while in a state of intoxication may oft too need examination to see if the impression or ‘mark’ has a time-limited effect or is remediable. Great fun can be had with this effect at stag or hen nights I am told, as we inform the bride-to-be that the evidence of her pre-nuptial misdemeanors are written on her skin forever, whereas we have only faked the impression of the tattooists needle.

We all like to ‘make a mark’, and this is what, I think Benjamin Myers novel Jesus Christ Kinski is really about – how impressions are made, sustained if we want them or removed, or modified if we don’t. Some people have little enough capacity for making a mark, either because their resources for implementing a mark lack power or capacity to stay in the memory of those who witness that mark or because they are trying to project themselves onto a medium that is heavily resistant to receiving impressions. Nevertheless strange effects can occur through over-control of the means of making your first impression.

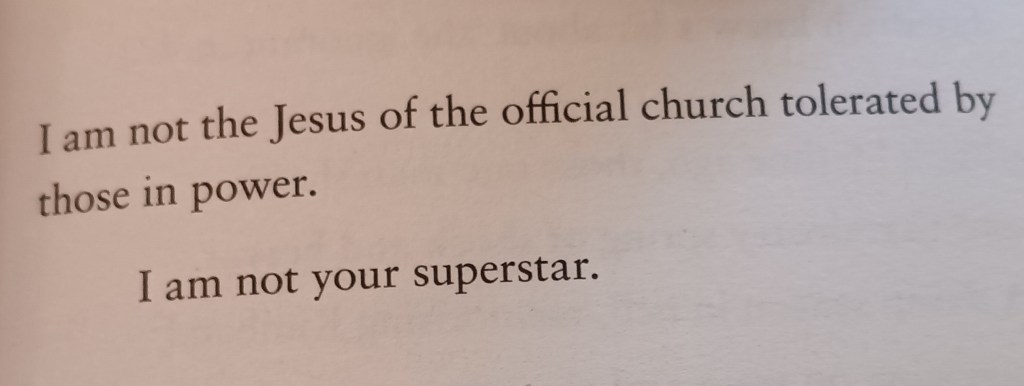

This novel concerns Kinski’s performance of a monologue, which is also filmed, written by himself in which he narrates and enacts the fate of Jesus Christ but is also an opportunity to rehearse how other figures who have needed to make an impression, place a mark on history, have done it. Kinski aligns himself not only with Jesus Christ but the virtuoso violinist performer Paganini and Adolf Hitler. He performs on the 22nd November 1971 for his recalcitrant audience in the Deutschlandhalle in West Berlin, built to celebrate events marking the expected long duration of the the Third Reich, and where Hitler himself made a debut speech, though Kinski relishes that the accomplishment of the Imperial impression Hitler favoured required very large enhancements, devised by other hands, of Adolf’s audible and visible presence. As Kinski thinks this he is aware too that his 1970s audience will see him as a ‘fascist’, a ‘Hitler’, a mark of identity he both does, does not, or does not care whether it is true or that he wants it or not, all simultaneously. But he knows he could, should he wish, outperform Hitler on making his impressive mark on this stage

The Führer spoke right here on this stage, though they had to turn him up to be heard – the little man never could project without trickery – and deck the place in gaudy banners and all that horse crap. None of that is needed for Kinski, no, not when the words themselves are enough. A microphone and a spotlight are all you need. [1]

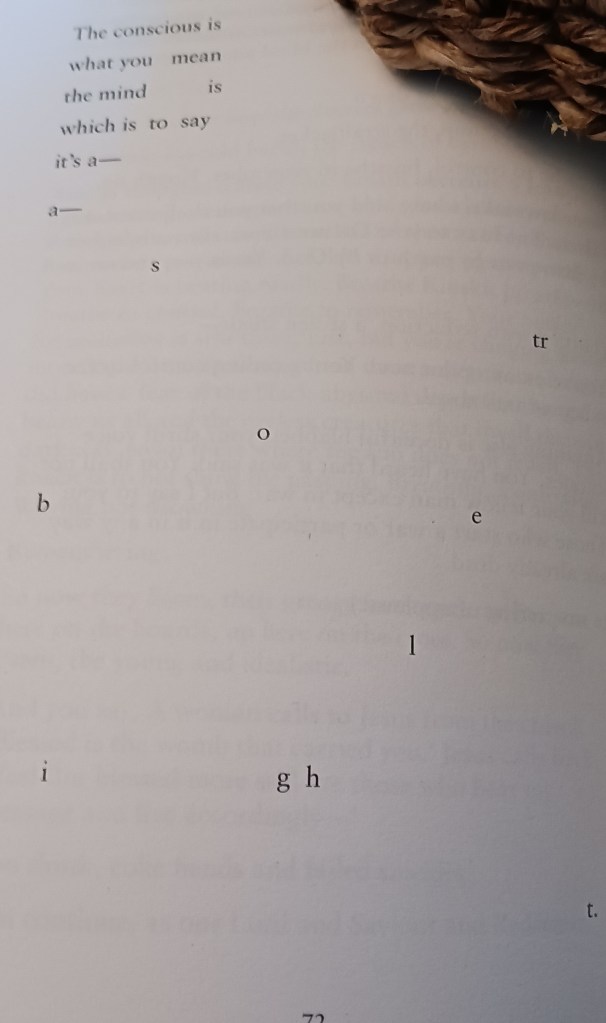

Kinski thinks this at this early point, but is soon disabused of his control of the impression that he is able to make, at one point seeing it dissolve in theatrical technique through his experience of using a strobe light, which in the sparking into his monologue on stage becomes a metaphor for the conscious mind lighting up across vast spaces of the unreadable unconscious. And the page opens up what it means again to ‘make an impression’ – in this case a printed impression, a ‘mark’ of ink of uncertain meaning.

For Kinski, Myers might think the conscious mind only highlights fragments of sense (in the page above these fragments are single or sequenced letters). Why else organize the ‘written’ word in this random spacing that makes it difficult to reintegrate it into a word, against the background of a vast unknown – to which there are no clues – metaphorically as a blank page interrupted by single marks, none of which is meaningful in itself. Kinski, in this book, lives in the random recollection interspersed into the present script – the script he enacted at the scene of Hitler’s triumph – of his supposed voice and which has found its way into the novel through the ‘authorial persona’, that one who might be Myers, having an obsession with Kinski’s impact.

Now, the impact of a man like Kinski, who is not a writer, or whose writing is ‘boring’ as Myers’ persona says the script of Jesus Christ Redeemer is (a script written by Kinski himself) is in performance or in the manner of mediating that performance – hence the long subtitle of this ‘novel’ – and that performance the Myers’ persona says latterly as he addictively watches it on video is in fragments brilliant and riveting actor’s performance: ‘The power of the bold act, the definitive night that can shape a life’. Nevertheless an actor is not a writer – and all Kinski gives is, in the end, a version of his multiple self – keeping the body that houses those selves in the spotlight or juming into the temporary domains lighted by a strobe light. All Kinski wanted was to make visible the ‘eye’ (and ‘I)) of a storm’ that was the ‘chaos, disorder and disruption’, that was all he could see of the world, and all he needed others to see – the only mark nd impression that he needed to create:

Perhaps what he wanted all along was to provide a memorable evening for all comers, one which capitalised on his monstrous ego, years of acting experience, notoriety and mental health problems. Or maybe there was more to it than that: maybe Kinski was reaching down through the decades that were yet to come and making a bid for immortality. [2]

What kind of impression do you want to make. Do you want to lovely as a passing day Shakespeare says to his boy love in Sonnet 18 or do you want me to make you immortal – which only an artist can thus write your impression into other ‘men’s’ eyes:

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st;

Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st:

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

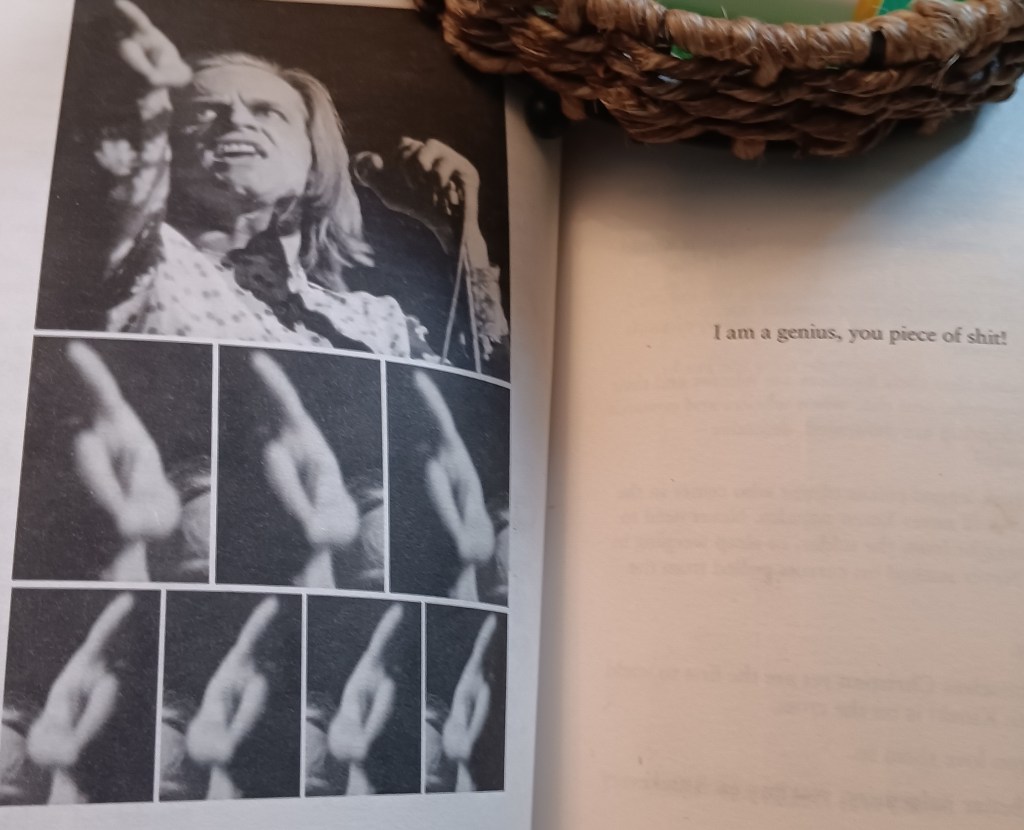

Of course Myers is not Shakespeare but the problem with Kinski as Myers shares his impact is that impacts, impressions or made marks can rely just on the volume of one’s voice (represented in font size or spatial isolation in text perhaps), the brashness of his gestures and self-statements – especially pointing fingers and sneers with over-simple short sentences – or the use of extreme swearing in place of exposition (nowadays we have Twitter/X do that for us). And you can imagine you make more of an impression by promoting yourself without much evidence of underlying talent and at the same time abusing and degrading your audience: ‘I am a genius, you piece of shit!’

I suppose this is why Kinski has so many personas. Not all of them are his – the role of Iggy Pop is thrust upon him by Myers. Hitler though he courts despite his proclaimed anti-fascism and his anger at audiences who name hi ‘fascist’ yet he insists that when he plays this impactful personae they differ from their established interpretation, despite the hand gestures (Myers book uses photographic collage brilliantly).

He is not the standard Jesus Christ in his monologue either. His Christ is not in the hock of established power and neither is his Hitler (or his Dracula or any other Herzog role):

But the puzzle of this book, as the authorial persona voice keeps telling us, is why should any author feel he can make an impression by examining someone whose impression is made mostly from such flimsy and hated materials. Myers, if it is his voice for he names neither himself nor his books in so many words, appears in parts of the book that are printed as if in newspaper columns, two columns per book-page (see one below). In the page I print below the authorial voice speaks gently of his difference to Kinski: hoping ‘to document history from the eye of the storm, as it were’ (thus quoting the very words he will have Kinski’s consciousness speak). This author has spent too long on Kinski, but in the gaps of his obsessive periods he has made some public impressions or marks himself. In the passages below he describes the novel that first made an impression – not his first – and a novel that is described as if it were, perhaps, Myers’ The Offing (see this link for my blog on this – he will later describe Cuddy which I blogged on here). [By the way, since many novels complain of the state of affairs what I think of as The Offing may have been Rare Singles – my blog here – except for the career timing and impact of the earlier novel].

Clearly if you can write something that even you can call potentially ‘twee’ (excessively or affectedly quaint, pretty, or sentimental), it is likely that you manner of making an impact or a mark will not be by the violent physical, verbal and statement-like blows of Kinski. This writer is always surprised when he makes an impression – the only one that really grabs him is that he makes on his new thick carpet he used the proceeds of surprising bestsellers to buy and mentioned near the end of the book, with a new house on the sunny side of the upper Calder Valley (those valleys are deep and dark). This writer still feels that it is likely that the impression and mark we make will not be that we intend or desire. Myers wants to warn the world of global extinction but he gets praised perhaps for appearing meekly twee but this writer is obsessed by Kinski because even the braggadocio of such a putative genius does not make the impression or mark intended but quite the reverse – or worse. Is this sentiment where we end with this novel and this writer, whom I love. Watch the world burn and its species die and then write your observations but:

… then this writing endeavour would be entirely futile anyway.

Of course, as a writer he already implicitly understood that in the grand scheme of things most endeavours were entirely futile, and that writers were no better than anyone else. Often they were worse, as they served little practical purpose beyond documenting the here and now in only slightly better grammar than those doing exactly the same on social media. No one seemed to believe the trusted narratives anymore anyway: a dire and dystopian state of affairs.

Now wouldn’t I love to make my mark – deepen an impression of my possible wisdom, by finding succour beyond this despair – in Myers’ novel or my own worse grammar – but I can’t. This novel is not for all but those who get it will adore it. We make our MARK – our IMPRESSION – anyway, but no-one can control how it is read. Note Creon to Oedipus at the end of Oedipus King of Thebes.

Seek not to be master more.

Did not thy masteries of old forsake thee when the end was near?

That’s all for now

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxx

____________________________________________________

[1] Benjamin Myers (2025: 55) ‘Jesus Christ Kinski: A Novel about a Film about a Performance about Jesus’. London, Bloomsbury Publishing.

[2] ibid: 192

[3] ibid: 104