This blog is written after seeing Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull as adapted by Michael Poulton at The Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh on Wednesday 29th October at 2.30 p.m.

Let’s start with the fact that John Poulton calls this version of The Seagull not a translation but an adaption. Nevertheless in his programme note he makes it quite clear that he had not intended in adapting Chekhov to make an ‘unwise attempt to “modernise” his settings’ nor the ‘fatuous attempt to make his plays “relevant”’. The hallmark he gives his adaption is that it ‘trusts’ Chekhov. I cannot judge the success of his attempt for I have no reading knowledge of Russian, nevertheless there are interpretations I give of the play in my earlier preview blog (accessible at this link) based on reading Constance Garnett’s aged translation that are not sustainable in the words of this adaption, for the characters, especially Mina, brilliantly performed by Harmony Rose-Bremner, that are much more nuanced than Garnett suggests, or at least I think so. Nevertheless Nina sustains the potential of development mainly because she survives and refuses to be tied up again with Treplev. Nor can I, with any confidence, guess at what made the text feel so much stronger and more living than Garnett’s having no access to it except an unreliable memory of hearing its words spoken and embodied. In some ways I balk at this because I have no great empathy with Poulton’s critical take on Chekhov drama as he explains it in the theatre programme at least. In Poulton’s words:

I hope we come out of a Chekhov play feeling that we love him and his characters for all their adversities, pitiful ambitions, and foibles. Chekhov is easy to translate because human nature never changes and his focus on humanity is so sharp and truthful.

I can’t agree that ‘human nature’ is such a constant as Poulton argues and that the relation of character to the specific determiners of time and space do not play a part in mould constructs of what we call ‘human nature’, not least because for me – even without Russian – Chekhov is as much as Shakespeare a dramatist who sees the moulding of each characteristic of a created human being as being at some level the product, if never totally, of history and political geography. And, paradoxically enough, the demonstration of this writerly characteristic emerged more strongly from this production and the text commissioned for it from Poulton.

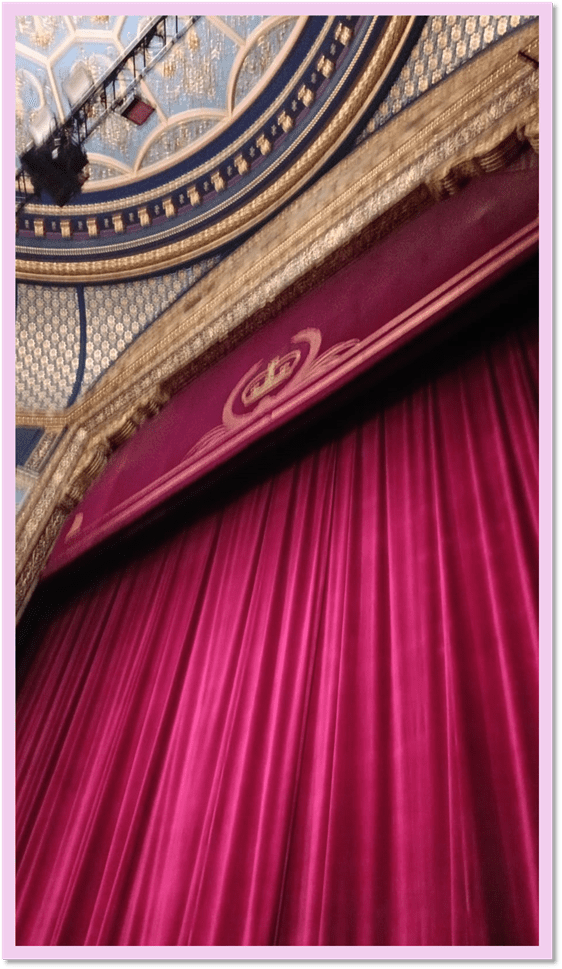

But Poulton’s take is so like the Lyceum; an old-fashioned theatre that still believes in the need to sustain a curtain to hide its sets before the play begins, as if theatre were a temple to the ‘revelation’ of humanity – a never-changing humanity but nevertheless one that reveals itself only in ritual – here the ritual of the theatre. But even though Stanislavski did the same in his naturalist theatre in Moscow does not suggest that we need the ritual theatre of the machinery of illusion as a revelation (raising curtains, sets and costumes that wind their own evocation of the real) in the theatre today as it is today to be the means of access to the crafted representation of the human and natura reality. Yet the Lyceum oft gives us that, though it varies by virtue of the particular production. We ought to be used now to the fact that artifice and nature are not binaries but combined across a range of differing possibilities. Why then, use a huge satin curtain, especially in a play that has a curtained stage as part of its first Act setting.

After all there is more than ‘character’ in a play – even in social comedy. Character, as such often reveals itself after all in terms of attitudes to categories of life’s sustenance that everyone recognises as ‘real’, such as the possession and use of money. Vital to the play is its setting is the decline and relative poverty of the great feudal estates of Russia – of the many great houses on the edge of the lake on which Sorin’s estate itself stands that no longer play music in the evenings and can no longer sustain the domestic economy of their houses with their parties for the urban elite who can be put up in them. Sorin can no longer sustain even carriage horses that are not absorbed into the agricultural economy that was once the unseen work of the estate. Arkadina cannot be taken to town at harvest time for that reason – estate managers have to exert power to remind great landowners of the basis of their present wealth in land.

The new generation of aristocrats like Konstantin can no longer assume the entitlement to write in a theatre governed by money and the sale of theatre tickets in the urban centres, and Konstantin, Sorin tells us has not even got a great coat to face he Russian winter or more than one pair of shoes. But likewise, those that have money, like Arkadina, have it and refuse to acknowledge that they have it, as if she were owed a living from the old order she came from one not the new one in which she is a saleable commodity on the stage. None of this is simply about ‘human nature’ but the construction of the concept of ‘human nature’.

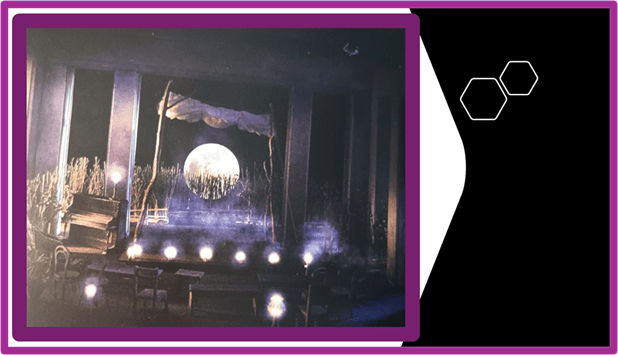

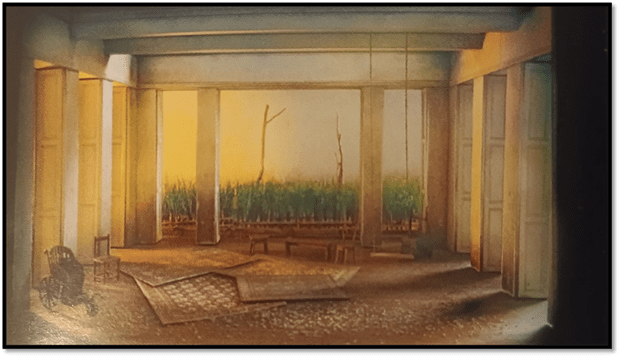

Yet the trapping of aristocratic wealth continue at Sorin’s estate, though the natural world therein is no longer subject to its owners, but a thing to be preserved in itself. Hence the care taken to focus the proscenium stage in the estate in which Konstantin will stage his play. It is a framework only – its setting real nature, though ironically this can only be represented by artifice. Here is the designers’ (Colin Richmond & Anna Kelsey) model set for Act 1, in which a huge moon, created by stage lighting, represents the night setting of the play and its reproduction. The whole thing is an ironic take on Stanislavskian naturalism. But when the play was staged the curtain was no longer the drop down one shown here but a white version of the huge satin curtain of the Lyceum, hiding the glories it will later reveal.

Speaking of which ‘glories’ I have a story to tell. I was sat in Row A of the Stalls and because the cast sat as audience to the play within a play on the stage itself, the action on the stage was occluded. The seats next to me were empty in Part One, that was because their occupants were late and sat further back in the theatre to avoid disruption. During the interval I mentioned that they had a better view of the inner stage than we did. ‘You mean’, a rather pleasant lady said to me, ‘that you did not see Yakov naked on the stage’. Yakov is a serf on the estate, who takes a swim in the lake before the production but is called forth by Konstantin as the play is in preparation and is, for a brief time, fully frontally naked before both the audience on and off the stage. I blushed rather that this lady felt I might have been disappointed not to see this, Yakov being played by a young martial arts instructor from Falkirk, Kristian Lustre, whom nobody, I gathered from this lady, was going to tell him that, in this play, ‘he only had a small part’.

The point of a play within a play is of course (it is so in Hamlet too) to play off the idea of human against artificial performance but in doing so to use the fact that they are not binaries – all action is in some way performative, in a theatre or not. In the company stills, Nina’s enactment of Konstantin’s lines about a nature robbed of animal animate life pits Nina against Arkadin, who sits on the front row on stage pouring scorn on the immature enactment and tedious amateurism of the concepts in her son’s play. However, we know that she misses the point. Konstantin is emphasising that the world trapped by the forms of the old arts is itself a confining thing – even concepts like character and settings in domestic spaces recreated. His theatre wants to take in the world and its soul.

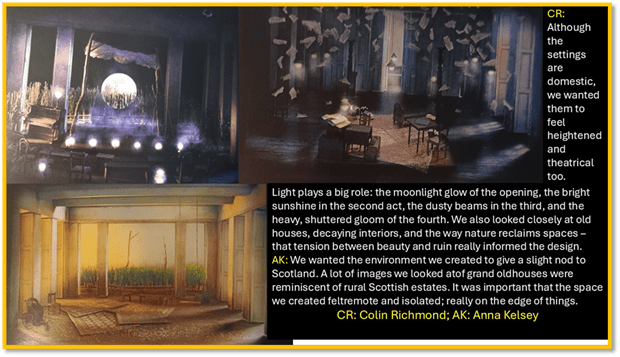

What is domestic and what is not, what is a home and what is not – all of these things help construct ‘human nature’, and yet they are constructions not of human psychology but of politics, economics and social ideologies. The designers made this important in their production, saying of the settings;

What matters is not a contrast of human nature and artifice but the fact that each interacts with the other in interpreting time and space and scene settings are an ideal way of showing that. Look again at these act 2 designs in which the ruination of the state is made analogous to the physical decline of Sorin, whose ‘bath chair’ increasingly spends much time on the stage.

One of the theatre stills shows how that is realised and characters and manufactured artefacts melded, ‘nature’ showing itself intrusively as intruding in to the construction, awaiting reconfiguration into a new ideology of human nature. This is performative of convention still – while the estate manager Shamrayev shows he has a right now to challenge aristocracy, serf Yakov still maintains a social role at the back of events: Nevertheless the configuration of roles on the stage make the lower class Shamrayev the focus of attention, even of Arkadina, who still thinks she is better than to be dependent on his economic role of maintaining the estate. but the a

She has still the right to play, as a swing on set shows, and to do this with style – and still not use any of her personal wealth to sustain it.

Arkadina is a great role and a tragic one, but I think I was wrong to ask to see the tragic dimension of her enacted and performed in this play, other than in her constant references to Shakespeare. Poulton increases these in his text – Arkadina even quoting Lear’s words on mortality as about ‘we unburden’d’ who ‘crawl towards death’. But human nature for Arkadina is never seen other than enacted, even in her most moving scenes with young men who challenge the limits of her power – Konstantin by evoking his ability to die before her or younger lover Grigorin to play with other younger women. When the play ends, she dies ignorant of Konstantin’s suicide.

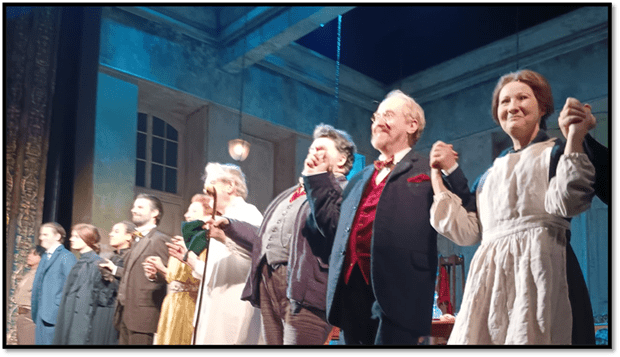

All that remains is for the grand actress, and Quentin does it brilliantly, to enact her curtain-call reception. But in Act IV, Arkadina twice makes reference to the wonder of her life being in such public receptions of her acting skill – in the theatre at Kharkov in fact. We should not ask the actress playing her to provide a picture of ‘natural’ grief – for her tragedy is that all is stylised and conventionally performed – in ways that make for ironic humour in a great actor – so that even in the Lyceum curtain call above I was moved.

But what a splendid ensemble company. When the stage goes dark Dr Dorn has just told Grigorin to ensure Arkadina has no knowledge of her son’s suicide- not in the enacted publicity of that final scene. And yet – all we see of her when the light lifts is the curtain call reception she embraces. The life of an actor!

I have a dreadful cold and have messed up the stuff above. But that will have to do. All for now, until I start something else.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxx