Geoff and I see a performance of a contemporary version of Indian classical dance at Bishop Auckland Town Hall on Wednesday 15th October, 7.30 p.m. It is on a vitally important theme of the moment: family and distance in migrant experience Fatherhood

Imagine a performance in which one man invests himself in the personality of three embodied men and many more unembodied roles conjured by interaction with their absence, through gestural proxemics – embodied actions which conjure the proximity or otherwise of the other, including the use of writing over distances. And voice appears to animate others suppressed from realisation, sometimes in oral language and the suppression of language in some excluded forms. Sometimes that language, from a letter takes a role, or when a greater psychic distance yet – absent selves speaking to absent selves – in a poem projected on the screen and itself acting up by its mode of transcription and motion – lives waves made up of language we expect to be linear and undulating – sometimes in multiple directions, sometimes overlaid as if in a projected palimpsest. There you have a taste of Fatherhood, a multi-generic performance-art form. Where the distance between dance and other human motion and gesture is a porous line, and where dance is or maybe ritualistic and coded or indeed not.

When Katie Ryan saw this work in Birmingham in 2022, she made much of the fact that the actor/dancer of the performance Shane Sambhu was trained and practised in the ancient form of narrative dance called Bharatanatyam, Ryan speaking of his ‘natural confidence in the form – he trained in it from the age of 10. Bharatanatyam was devised (Shane told us in an after-performance chat with his audience) from the powerful traditions of the courtesans of the courts of and religious places of Tamil Nadu from a semi-divine and semi-profane form or erotic body expression. But Ryan’s point – I think because she never elaborates it or says more about the transliterated Malayalam words she uses – was that that though clearly a highly coded ritual dance form, its meanings were never fixed (a point emphasised by Sambhu at the after-show talk) but rather suggestive of meaning. Ryan merely gives us the term to describe this expressive ambition in South Indian art which leads or guides to a mode of feeling through different simultaneous media, abhinaya. Wikipedia further glosses this term by pointing to its four interacting and interrelated aspects of expressive media (material and otherwise): ‘angika (the body), vacika (the voice), aharya (costumes, make-up, scenery), and sattvika (mental states)’. The point is that there is no given meaning to a dance sequence’s expression but one emergent from the attentive watching of the performance, and its life in its witness (cognitive, emotional, visceral …) thereafter. That came home to me when I asked Shane about a particular dance sequence associated with his unseen father on stage, involve movements of body that seemed to expand the dancing form by drawing out mental viscera from the transforming body shape. Shane said this was not to be mistaken as an orientalised meaning code but a mediation of what the father-son relationship felt like that transnational and trans paradigmatic – he even invoked notions of the Oedipal struggle within male identity as a possibility within it.

Ryan expresses all that thus in a delightfully chatty style I envy, despite the lack of gloss on the Malayalam terms:

With the natural confidence of a Bharatanatyam soloist switching between roles in an abhinayapresentation, Shambhu’s great skill is to slide between characters with total conviction. Watching the instant transformation of physical and vocal personality is mesmerising. Peppered with comic moments, the pace of change keeps the audience engaged and working to fit the fragments of narrative together. Shambhu juxtaposes moments of light and dark, tenderness and rage in a striking way: the tiny fluffy lamb becomes a bullied child as three toy dogs surround it ominously, the roar of a man protecting his assaulted wife morphs into the roar of a father in a game of chase with his toddler. We are both moved and shaken by the emotional rollercoaster of the life of a father.

But let’s not stop there with Ryan for her overall summary too is invaluable, describing the multiple integrated ‘plots’ of the piece Thus:

Altered Skin’s latest work centres on the stories of three fathers, separated by space and time yet connected by the common experience of navigating their role within the South Indian diaspora.[1]

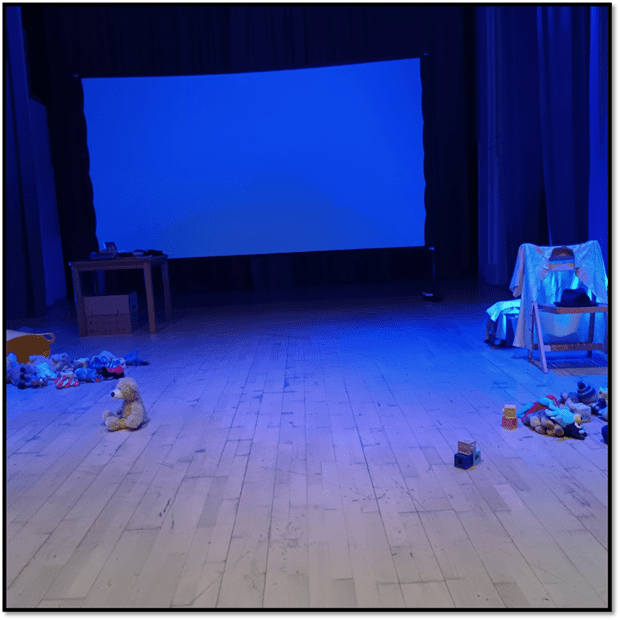

Before the performance starts we can not imagine the richness to be achieved by its base materials, as in my photograph below:

Simple materials! That screen allowed words in different languages not only to be read but to use their shaping and manipulations to dance, particularly wonderful when the written form of Malayalam, with its rounded script and flowing elaboration was used (see the word Malayalam in its own script (from Wikipedia of course) below.

Scattered chairs and tables could house other characters or become a mountain from which to view the meeting of three oceans from the tip of the Indian sub-continental peninsula, discarded shirts and hats make for character transformation markers. Toys make for wonderful means of demonstrating abuse with no lack of emotional reaction and little of what we like to call catharsis, so instinct are they with the life of childhood. Toy baskets could become modes of transition by boat (either real or metaphorical) – inhabitants sometimes played by the toys of the 21 months old child imagined on the stage from absence – in migrations other than ones, but including them – of cognitive and emotional time and space. And we remember that not all languages are divorced from gestural coded embodied forms, such as the Indian sign language used by one of the fathers played by Shane, described by Ryan well as ‘Raghavan, whose life journey, narrated in voiceover by his daughter, traces through Tamil Nadu, Singapore and Great Britain at the end of the British Empire’, a man who also signs for himself that he is alienated from Indians by his reliance on signs and from deaf people by being Indian in that historical conjuncture and phase of global migrations.

The stress on fatherhood is not though borne out by the fact of three fathers in one, but in the work’s insistence of how and why ‘fatherhood’ and its authorities, or lack thereof, is transmitted laterally down lines of both descent, culture and language – the processes of selection in that transition that occur being highlighted. This is so particularly in the crux conflict between Hariharan, who everybody even himself until the awakening at the end Anglicises as ‘Hari’, blames his father for not passing on his Tamil culture and Malayalam as language to his son in his inability to do so – for his father never passed on these objects of inheritance to him.

There are necessary selections in that passage of supposed heredity, of course. As Ryan says:

Shambhu questions how best to raise his son, rejecting the traditional gender roles of his parents. He muses on the migrant experience common to both his father and father-in-law, and the rich yet complex multi-lingual heritage of his son. Language in all its forms, as a connector and barrier, is a central theme. English, Malayalam, Persian, German, Tamil, sign language, live speech, recorded speech, written text, Bharatanatyam…the multiplicity is beguiling and overwhelming.

I didn’t find the overlay of languages ‘overwhelming’ because I accepted the barriers to full communion as part of the experience of communion. Moreover, it emphasised how much of the history I have lived through, and that has shaped me in the world is neither mine nor that of a family purely biologically considered. It must speak and be written through cultures that I can never fully understand, even that of deaf communities, as well as ones that I think, though I am not necessarily correct in my thinking, I DO UNDERSTAND.

That is because the subjectivity I am must be reducible to, at some level of analysis, must bear the benefits and deficits of the colonial exploitation of my ‘race’ and culture. The working class in England is currently at its most ignorant rejection of migration, but that ignorance was in-formed in the class and me by the leisure of being complicit in exploitative colonisation. The ignorance structured within us included Malayalam and the cultural products of it that we shaped in order not to threaten us. Bharatanatyam is a case in point – robbed of its power, especially that was female in origin and eroticism. Instead it is exoticised (orientalised) in order to look safe to us, as an aesthetic minor and local form not an exploration of social and cultural power that privileges domestic aspects of identity and makes others part of an.oppressed, marginalised silence.

In my primary school days, because textbooks were old, the world was still coloured pink in school atlases. By this device, we were taught subliminally that we were fortunate to require only English in order to speak at others, for speaking to or listening was not required. In the disgraceful state of our education, this may be all the culture the working classes were ever offered systematically, with some pockets of exception.

We are necessarily cut off from some traditions, which ought to be part of our memories. And we must struggle to win back these memories. Which are ours by virtue of being those of significant others, without, of course, appropriating those memories as solely ours. It is thus that I read Ryan’s rather lovely summary of her impressions of this work:

Although each narrative thread has some sense of resolution, this is incomplete, and rightly so – these are challenges and stories that continue from generation to generation. Clearly inspired by the deep love of his son, in Fatherhood, Shambu puts the challenges of modern parenting and the complexities of the migrant experience in the spotlight it deserves, and does so with intelligence, humanity and compassion. Touring widely in 2022 and 2023 I have no doubt this work will resonate with audiences across the country.

But resonance is not proven. There were at lost only ten couples at this performance in a town which has recently hosted small but noisy semi-fascist rallies [one last weekend in Crook]. The issues seem today more urgent than art alone will be able to address. Yet current politicians are happy to see culturally critical multicultural education die in order to bow to voting expressions of ignorance that it seems in no person ruling in the status quo to challenge.

All for now

With Love

Steven xxxxxxxxx

[1] Katie Ryan ‘Review of performance with Shane Shambhu at Patrick Studio, Birmingham 27 October 2022: Fatherhood- Altered Skin’ in Pulse (online) [10/31/2022], available at: http://pulseconnects.com/fatherhood-altered-skin