What happens when artists are asked: “What have you been working on?”

What have you been working on?” is a catch-all question? Does it ask what task are you currently working towards completion. It might mean that and it might at the same time refer to a task in at your paid work role. Alternatively, it might refer to some larger DIY project in home or garden. Even so, it it is not specific to the stage of any of the pieces of work. You may, after all, not even have a task defined as such yet but be ‘working on’ defining a task for yourself or planning to define that task ‘some time’. In the latter case, the ‘what’ can be very vague indeed, for the work is precisely the work needed to clarify the aims that identify things you need or want to work on?

Moreover, sometimes to ‘work on’ is often used to mean what task or aim are you picking out for attention out of a possible repertoire of necessary or eventually-to-be-completed tasks. This is the case in the gym where people work on particular muscle groups before moving on to others, or in counselling where we work on one facet of our behaviour, feeling or thinking at a time: ‘I’m working on my feelings of inexplicable self-dissatisfaction’, for instance.

And ‘work’ is a problematic word in itself, implying a labour done in order to achieve some external object, external even if abstracted from an invisible product that defines a characteristic of ourselves like working to find some determination in a world that feels to you as if it required tou to both identify the repertoire of choices ahead of you and make one choice from that repertoire. Aren’t there also often undertones to the phrase to work on something, where some inner voice says ‘real work’ is ‘paid work’: work that has an exchange value and is productive?

However, how do artists answer the question, what are you working on now? That is a question I started to think about yesterday (the 11th of October) at my one day at the Durham Book Festival. I had booked for two events at 2.30 p.m a reading of poems written in commission to Writing North under the title Rewriting V by Paul Farley, Malika Booker, and Jo Clement, , an event chaired by the poet and novelist Andrew McMillan. I will come back to why that event seemed relevant here later. The second event, where my husband Geoff joined me, was a huge one about a work-in-progress, due out in 2027, and to be entitled Dipped in Ink and therefore obviously an answer to the question, ‘What are you working on’ given jointly by Pat Barker and her daughter, Anna. Again, I will deal with this separately later, though the event opened with Anna Barker reading out the epigram to the work, from Alexander Pope’s The Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot, in my view, his best poem and one addressed to his friend and medical physician. She read the first two lines of the episode of the poem, wherein Pope tells us that he was born singing in metre, such that the cause of his drive to being a writer could well be a deviation of his own nature or one inherited:

Why did I write? what sin to me unknown

Dipp'd me in ink, my parents', or my own?

Clearly, this idea relates so well to a memoir that dives back into Pat Barker’s family history to find the cause of her being a writer, as well as forward to the passage of the writing dis-ease to Anna, herself now poet and novelist and now co-memoirist. To see the development of that idea, we will have to wait for publication in 2027, barring another event in sequel to this one. But, for my purposes in this blog, let’s take another extract from Pope’ best poem, where he tackles the question asked, too often suggests Pope, of: “What are you working on?”

Why am I ask'd what next shall see the light?

Heav'ns! was I born for nothing but to write?

Has life no joys for me? or (to be grave)

Have I no friend to serve, no soul to save?

"I found him close with Swift" — "Indeed? no doubt",

(Cries prating Balbus) "something will come out".

'Tis all in vain, deny it as I will.

"No, such a genius never can lie still,"

And then for mine obligingly mistakes

The first lampoon Sir Will, or Bubo makes.

Pope insists that writing is not an easy thing, but one that steals time, energy, and care from life, robbing the man Alexander of a life that is sacrificed to the poet Pope. And worse still what we work on – hard gruelling work that it might be even when it feels natural – is even so ill appreciated by people, and even critics are people, that they mistake the work of fools who still got published for some reason for the masterful work of Pope himself. So, in Pope’s words, we see some reason for poets, or other artists, feeling nervous to be asked what they are working on, and trying to explain to those who do not realise the labour and cost of art the things the work-at-hand attempts beyond the superficial ideas of the mere dilettante of art appreciation. And sometimes the life expended upon, and worn down by, art – that we tend to think of as a theme by W.B Yeats, is also one that Pope does passingly, subtly well:

Heav'ns! was I born for nothing but to write?

Has life no joys for me? or (to be grave)

Have I no friend to serve, no soul to save?

To rhyme ‘light’ with ‘write, next to a couplet rhyming ‘grave’ with ‘save’, hints of the death in life, Romantic poets attributed to their experience in the service of imagination at the expense of a truly lived life in the body and with other bodies, rather than imagined ones. Well that’s my fancy anyway. And it segues into a story told by Paul Farley, when he introduced his poem written in response to Tony Harrison’s V.

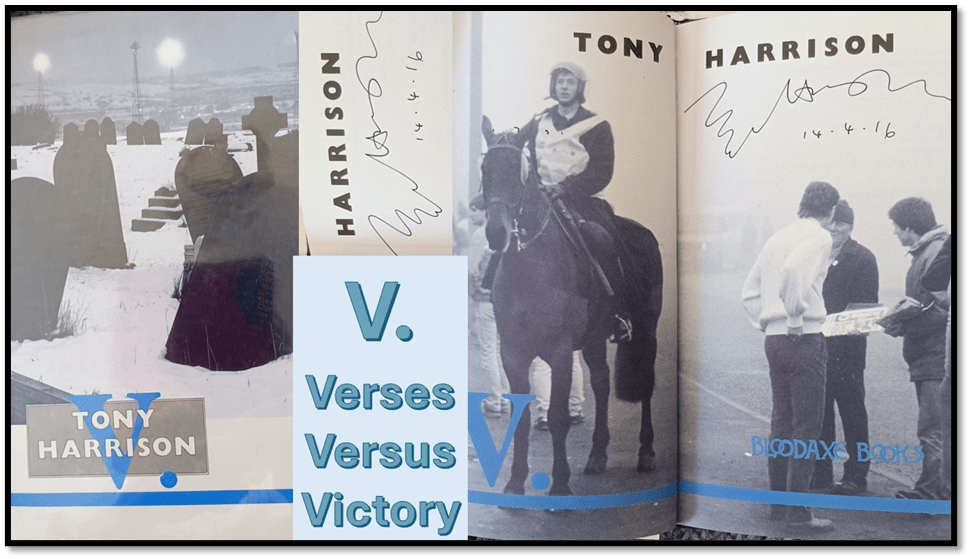

Photographs of my first edition (1985) of V, signed by Tony Harrison in 2016 on a visit to Teesside University for a reading. At the even, Andrew McMillan read from a copy signed by Harrison to Andrew’s dad, Ian McMillan, a well known Northern poet himself, and then gifted to son Andrew.

Farley introduced his ‘response to V‘ by telling a story of how in conversation with another poet (in Madeira in fact) he had answered the question of what he was working on by saying he had accepted a commission from Writing north to write a poem that responded in his terms as a poet to Harrison’s poem. “Are you fucking mad“, the unnamed poet responded. You need to get that point, to respond to Tony Harrison, and to V in particular, is to respond to one of the most singular achievements in literature. And Farley in fact rewrote the poem entirely on hearing of the death of Tony, which happened on the 26th September 2025, hardly a breath or two away from this event. Farley’s poem recalls an incident in which he stood with a poet on a visit to the cemetery in which Tony is now buried in the place he himself spoke of as his intended final place in V itself, looking at a sign in the cemetery that marked the spot, the same described in V where Tony would be buried. Harrison had expressed his feelings at having this place to relate to by a public body before he had even thought he was, in the short rather than long duration, dying. I had hoped to remember lines from this poem of friendship and comradeship in art but it has gone too much for me to be confident to get it right, though the experience and the few tears, and warm laughter (so Harrisonian), prompted are a strong memory. In the end what remains with me is V.

Jo Clement was not present at the event, and her short poem, addressing class in Tony’s memory for he understood that concept, was read by Andrew McMillan. Malika Booker used the commission to finish a poem she had been troubled by – a retelling of the story of Jonah and the Whale in a poem that paralleled the Biblical story, in the king James Version, with other stories with a diaspora Caribbean voice, and about migrancy – the theme of the day. The aim was to use the shifts between tradition and invention that V also used and it worked, and though I was sure I would confidently remember some great lines, I don’t with any confidence. The point is that, in performance poetry, Harrison was genuinely responded to in the genuine human and humane politically aware and awake voices, but again it is V that remains with me.

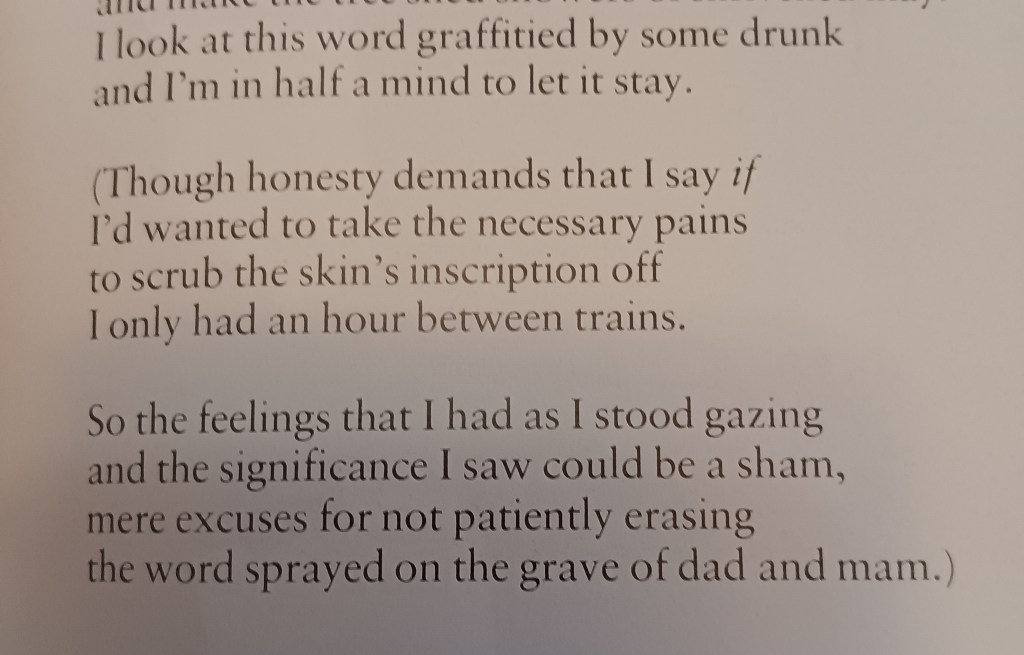

When I reread the poem myself before the event, I had Andrew McMillan and his recent turn, in his novel Pity (see my blog on this here) to the theme of leaving and returning to a Northern urban home from a city, for him the geographically proximate but socio-culturally vastly distant Manchester, in my mind for to me the poem , for that dialectic of serial leaving and returning marks a cultural experience for his, Harrison’s and, not to be compared just analogous and spoken for by them not me, my generation. It is a theme Pat Barker picked up in her event too. The fractured voice of the ‘home-returner’ is a full of a strange and queer broken emotion, divided between sorrow and relief (that escape from return is possible), fulfillment and dissatisfaction, moral achievement and grief in: ‘Flying visits once or twice a year‘. I’d found that in this section of the poem where the poet finds the word UNITED graffitied on his parents headstone but referring to the football team in Leeds not his parents reunion in death:

The verse here strains between ‘honesty’ offered almost intimately to the reader and painful awareness of the psychological awareness of the means the son turned man is cradling his independence of his parents – his ability to get away, again, replicating that first uncertain escape but now in fullness of needing it.

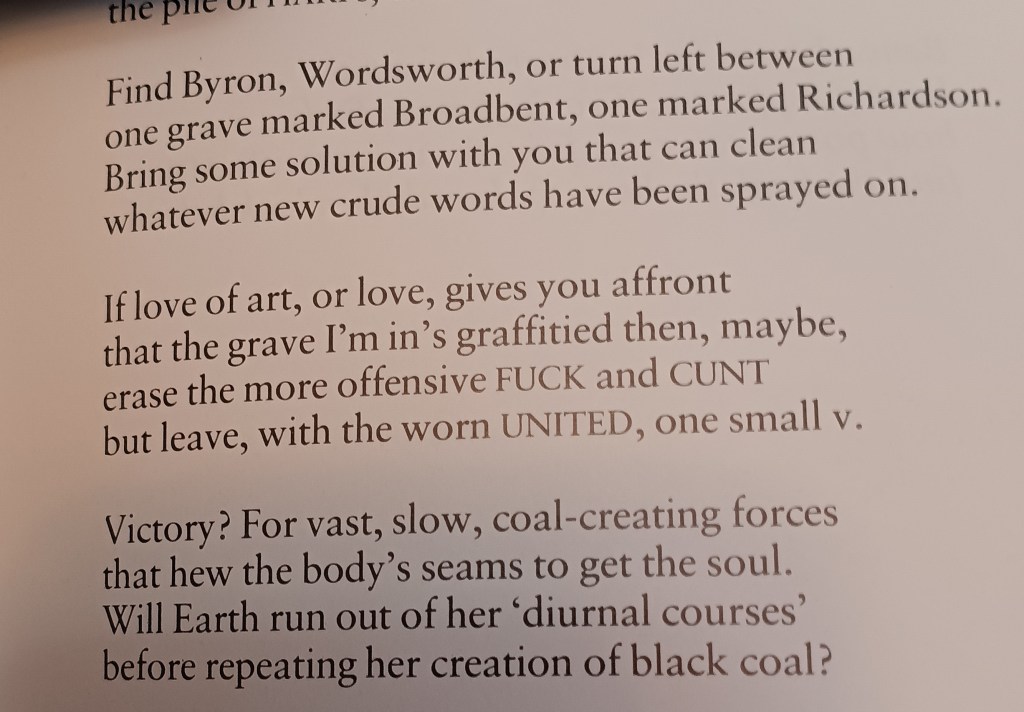

And when he does identify the place he will be buried, it is in awareness that he has achieved something greater than independence of his mum and dad, she still playing ‘Hamlet with’ him for his coarse obscenities that he calls poetry but a role in the modern pantheon, that he names, forgetting that the names are not those of poets Byron and Wordsworth, though signifying them here, but of Leeds bourgeois tradespeople no greater than ‘Broadbent’ or ‘Richardson’. And yet, as V morphs into the acronym for Victory, it is also the Vastnesses of the underground formation of coal for someone to dig it out again, only then to be thrown out of work as redundant. A poet learns he is not only less than geological forces, as Tennyson had, but of the human forces of an exploitative economy which produced the unemployed ‘skins’ Tony could have been, and imagines himself as in this poem, able to write only with a spray can, and unable to differentiate French from Greek, let alone translate Racine and Euripides as Harrison did.

And that bit there that is in scare quotes. It is a misquotation from the poet Wordsworth on the nature of deatj in eternity not the tradesman Wordsworth in the earlier reference:

All this I thought and felt, not least because suddenly I was visited by the ghost of Harrison who knew what we call ‘culture’, at least divorced and disunited by class, race and every other divider was a kind of sham. And then i thought of the artist McMillan and wished he hadn’t been so silent in his own voice – for it is a hopeful one.

Those thoughts must have scarred me for though I had my copies of Booker and farlety signed and read them both as I awaited Geoff coming to join me for Dipped in Ink, I suddenly felt ‘sham’ in that act of owning signed editions and gave them away to The People’s Bookshop in Durham so that some money might go to left causes and to Tony’s memory.

And then to the event with Pat Barker and Anna. A relaxed event where mother and daughter co-interviewed, for much was made of the difference in generation, and perhaps approach to art, as well as similarity, love and ownership of a common origination as writers, however separated its moments in time and history. See the collage of conversational poses and gestures below, for it gives a taste of the beautiful togetherness of mother and daughter.

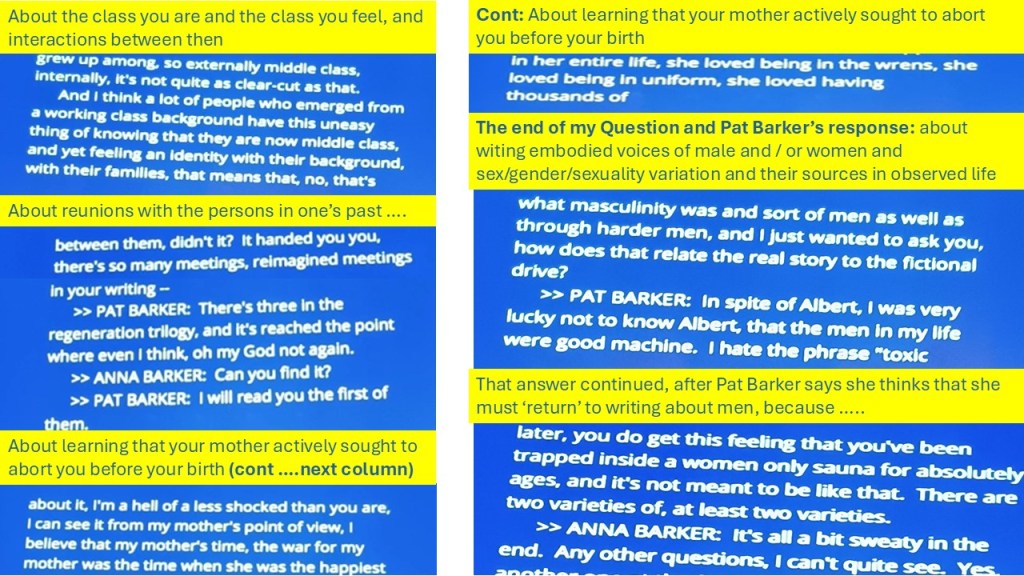

But these days, words said get transcribed (and very often mistranscribed to various effects) on screens behind speakers. So here are snippets – not always reliable. Pat Barker addresses class as if she were carrying on the conversation from the earlier event, where ‘knowing’ and ‘being’, the epistemology and ontology of if you like, being attributed to a class ‘status’ is made a problem, as it is for the characters in her fiction, from Billy Prior onwards.

How the story of a life of partings and reunions is reflected in the novels comes up too. Then came the revelation of the fact of Pat’s mother, Moira’s, betrayal by the sharp gangster called up into the army, Albert, who purposely removed his condom before ejaculation thus conceiving Pat, with no intention of being in a relationship or caring for Moira. The latter lost her place in the Wrens on her pregnancy being discovered but Pat, no friend of the ‘victim’ idea of female experience, though the stauncher feminist for it, compares her lack of shock at her mother’s attempt to abort her than Anna does, or so it is reported (Anna just brilliantly smiled). My question to Pat was about the mismatch between her awareness of the male hardness of Albert and her lifelong fictional drive to conceive of strong women in relation to softer men – not just middle class queer ones like Owen and Sassoon, but the range of Billy Prior in the Regeneration Novels and that wonderful male social worker in The Century’s Daughter (later renamed Lisa’s England). I had to laugh so much when Barker said she ought to get back to writing men (again in abandonment of that ‘victim’ woman paradigm of the ‘toxic masculinity’ analysis) because she has this feeling after her wonderful Homer Trilogy (see an example of my blogs here) ‘you’ve been trapped inside a women only sauna for absolutely ages’. as Anna says ‘all a bit sweaty in the end’.

If only you could have been there. I glowed with pleasure in the end at how wonderful Pat Barker was in her eighties. It almost wiped away my memory of having to pass through a fascist rally – in Crook of all places -on my way to the events.

Bye for now.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx