‘Be near me’: A good neighbour is one of those near to me who are willing to be still closer.

I will keep the English spelling of neighbour that is not used in the prompt question, that question having come from the United States who dropped the ‘u’ in words ending ‘-our’ long ago. However, I don’t do that with any sense of possession of that spelling as authoritative, for etymonline.com gives the same etymological history for both spellings with an explanation of the origin of the difference.

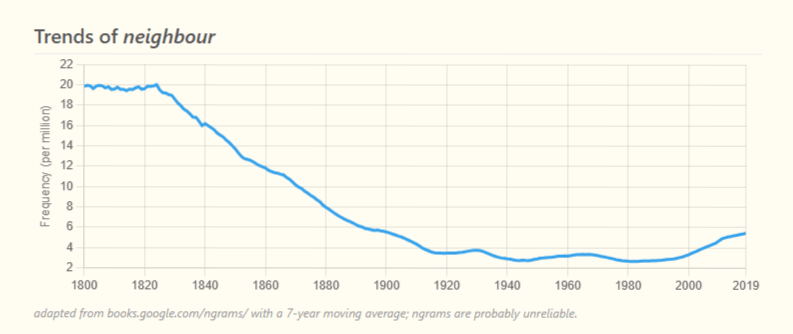

It would appear, however you spell it, that the word ‘neighbour’ is not used as frequently as was once the case (their n-gram starts at 1800) and this may reflect an increasing sense of the role of distance in interpersonal relationships, where ‘nearness’ is not a requisite of attachment. Nearness has always been a word with stretch in different emotional reactions to it, which is perhaps even more the case with the word ‘close’ or closeness. When people are asked to list the people nearest to them, they don’t start by measuring the distance from what they consider their significant boundary of self to that of another. In fact, as I increasingly think as I think about it, the ideal meaning of neighbour seems to many to being people who ‘keep themselves to themselves’.

The etymology is clear, a neighbour is one who lives near you: (here from etymonline. com, as the n-gram above). We speak of a next-door neighbour and some people only use this appellation of the person next door, whilst to others it denotes a community – linked by proximity and a dwelling area held in common – a street (Ramsey Street in my lead picture) or avenue, perhaps, in common with all others. in that street or avenue.

neighbor (n.): “one who lives near another,” Middle English neighebor, from Old English neahgebur (West Saxon), nehebur (Anglian) “one who dwells nearby,” from neah “near” (see nigh) + gebur “dweller,” related to bur “dwelling,” from Proto-Germanic *(ga)būraz (from PIE root *bheue- “to be, exist, grow”). A common Germanic compound (cognates: Old Saxon nabur, Middle Dutch naghebuur, Dutch (na)bur, Old High German nahgibur, Middle High German nachgebur, German Nachbar).

But for most English speakers, the word neighbour is a word that has equates proximity with likeness and sharing as well, and often becomes – too often in my view – a means of evaluating a neighbour for being or not being enough ‘like’ oneself and using unlikeness to prompt being ready to close the gap that leads from us to them in a way that resembles physical distance – because it makes each inaccessible to the other.

A good neighbour is a close neighbour in more than one way of being close in some communities – although I sense the trend is for a neighbour to be one who keeps ‘themselves to themselves’ as I said above and allows one space from their intrusion. Sometimes, these inversions of evaluation around the idea of community are linked to identity issues – class, culture, race, sex/gender, and sometimes skin colour. Do you remember the appalling racist 70s comedy Love Thy Neighbour, made into an even more appalling racist film?

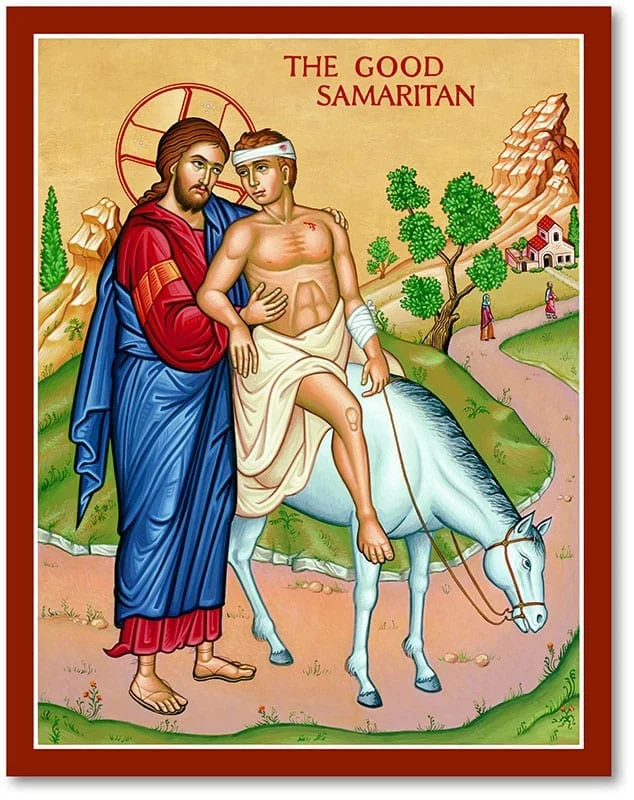

However, issues of ethnic culture are present even in the most famous story in which a neighbour is defined – Jesus’s parable of the Good Samaritan in the Gospel of Luke chapter 10, here in the King James version:

25And, behold, a certain lawyer stood up, and tempted him, saying, Master, what shall I do to inherit eternal life? 26He said unto him, What is written in the law? how readest thou? 27And he answering said, Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy strength, and with all thy mind; and thy neighbour as thyself. 28And he said unto him, Thou hast answered right: this do, and thou shalt live. 29But he, willing to justify himself, said unto Jesus, And who is my neighbour? 30And Jesus answering said, A certain man went down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and fell among thieves, which stripped him of his raiment, and wounded him, and departed, leaving him half dead. 31And by chance there came down a certain priest that way: and when he saw him, he passed by on the other side. 32And likewise a Levite, when he was at the place, came and looked on him, and passed by on the other side. 33But a certain Samaritan, as he journeyed, came where he was: and when he saw him, he had compassion on him, 34And went to him, and bound up his wounds, pouring in oil and wine, and set him on his own beast, and brought him to an inn, and took care of him. 35And on the morrow when he departed, he took out two pence, and gave them to the host, and said unto him, Take care of him; and whatsoever thou spendest more, when I come again, I will repay thee. 36Which now of these three, thinkest thou, was neighbour unto him that fell among the thieves? 37And he said, He that shewed mercy on him. Then said Jesus unto him, Go, and do thou likewise.

It is a difficult example tbis to weigh against our understanding of the English word neighbour, used in this translation, in part because in it who lives nearest is barely an issue since the story takes place in transit between places. Moreover, though the ‘priest’ and the ‘Levite’ are clearly orthodox Jews, and the Samaritan is not considered orthodox, place of dwelling is not the issue, except that we knew there was prejudice against Samaritans from orthodox Jews. But the real point is that Jesus defines the neighbour implicitly in the story by what they do in contrast to what the priest and Levite do.

The easy distinction to make in their behaviours is that the Jewish religious don’t give help and the Samaritan does, but what is a better distinction is that the former both ‘passed by on the other side’, whilst the Samaritan cane near to the beaten, wounded and naked man: ‘went to him, and bound up his wounds, pouring in oil and wine, and set him on his own beast, and brought him to an inn, and took care of him’.

I have always puzzled about this until I read this very fine analysis in a webpage of the Greek Linguistics website from May 2012 (see it properly at this link), entitled WHO IS MY NEIGHBOUR?:

Suppose my house is in a remote area with no one in sight to call my neighbor. Or that my neighborhood is spread over a wide metropolitan area. Would one living two miles away from my house be less my neighbor than my next-door neighbor? Jesus commanded us, You shall love your neighbor as yourself (Matthew 22:39, Mark 12:31, etc.). But who is really my neighbor?

This question echoes what an expert of the Jewish law posed to Jesus during a dialogue he was having with Him in public: And who is my neighbor? the man asked sanctimoniously (Luke 10:29), at which point the Master responded in the form of the parable of the good Samaritan. At the end of the parable, Jesus asked the law expert which of the three men in the story had been neighborly to the victim in need, and the law expert pointed out the Samaritan. Jesus commended him for responding correctly and advised him to follow the Samaritan’s example (Luke 10:37).

But the question Jesus asked of the law expert had nothing whatsoever to do with one’s house being near or far from a neighbor’s house. So how can we know how the law expert perceived Jesus’ use of the Greek term for neighbor ? For that, we need to examine two key parts of the Greek text that contain that term (given below in bold print):

1. Jesus’ challenger asks, Καὶ τίς ἐστί μου πλησίον; And who is near me? (Luke 10:29b).

2. At the end of the parable, Jesus asks, Τίς οὖν τούτων τῶν τριῶν δοκεῖ σοι πλησίον γεγονέναι; Which then of these three do you consider to have become near? (Luke 10:36).

Greek πλησίον [plision] near is an adverb that is commonly translated neighbor, a noun. It is a form of the adjective πλησίος (-α, -ον) which means one near, one close by. Though indeclinable, this adverb may be used with the definite article substantivally in reference to a person, e.g., τοῦ πλησίον (Eph. 4:25), τῷ πλησίον Rom. 3:10), τὸν πλησίον (Jam. 2:8), meaning the (one) near, nearby—that is, the near for short.

Like the law expert, we hear the Master say that nearness and proximity to another person is relevant only in terms of the action we take in the face of that person’s need. Jesus’ question was not whether the victim was near the three men passing by, but rather which of the three had become near to him (Luke 10:36). The Samaritan saw the victim and ἐσπλαχνίσθη [esplahnisthi] was moved by compassion (Luke 10:33). That means that we become near the moment we act with compassion toward anyone in need whom we accost in our daily path regardless of where we are or where we live.

The good Samaritan is in harmony with the Golden Rule (albeit this name is not in the Bible): Do unto others as you would have them do unto you (Matthew 7:12); and with James’ Royal Law: If you really fulfill the royal law according to the Scripture, ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself,’ you are doing well (James 2:8). Collectively, these and a good number of other scripture references both in the New and in the Old Testament portray a panoramic view of neighbor as one who, moved by compassion, pleases heaven by becoming near to someone in need.

Incidentally, Greek for neighbor is γείτων [yiton] one living in the same land (Luke 14:12, 15:6, 9; John 9:8) or περίοικος [periikos] one dwelling around (Luke 1:58, 65). Today these three New Testament words—πλησίον, γείτων, περίοικος—are spelled, used, and according to historical evidence pronounced the same way in Modern Greek.

Let’s linger a little while on the fact that had the Gospel writer meant merely to talk about people who live near to each other, he had other, less ambiguous choices in Greek than to use the term πλησίον, which is an adverb meaning ‘near’ but often understood to to mean neighbour by extrapolation. However, the Gospel writer chose the word carefully, for it gives away the kernel truth of the parable.

A good person approaches nearly to you, even to your brpken skin, and is not afraid of the boundaries that make you different from themselves. They share of themselves – their warmth and care. This answers all my problems about this long known story, but it also brings the emotions and sense responses of nearness as well as the physical contact to bear.

In the head, at this point, a lyric [number 50] from In Memoriam pours its evocation of the senses over me. It is a lyric full of visceral sensation – you feel the edges of the body, and it defines the neighbour who will come near to the lyric voice at his lowest – neighbour, friend, the dead man Arthur Hallam whom he loved, who once wrote a paper ‘On Sympathy’ to read to the Cambridge Apostles when both he and Tennyson were members. This lyric is the meaning of ‘sympathy’, taken from Adam Smith’s views on it (see my blog that mentions this at this link).

Be near me when my light is low,

When the blood creeps, and the nerves prick

And tingle; and the heart is sick,

And all the wheels of Being slow.

Be near me when the sensuous frame

Is rack'd with pangs that conquer trust;

And Time, a maniac scattering dust,

And Life, a Fury slinging flame.

Be near me when my faith is dry,

And men the flies of latter spring,

That lay their eggs, and sting and sing

And weave their petty cells and die.

Be near me when I fade away,

To point the term of human strife,

And on the low dark verge of lifeThe twilight of eternal day

Maybe I reflect on nearness and closeness too much, but more people than myself find it a puzzle, although the word associated with closeness may be lover, partner, spouse. We hate to be apart from someone who ought to be close to us? And when we are we feel viscerally the distances involved, but sometimes these feeling come to roost in an understanding that perhaps wven when we were close, we might really have been distant: neither neighbours, lovers, partners …

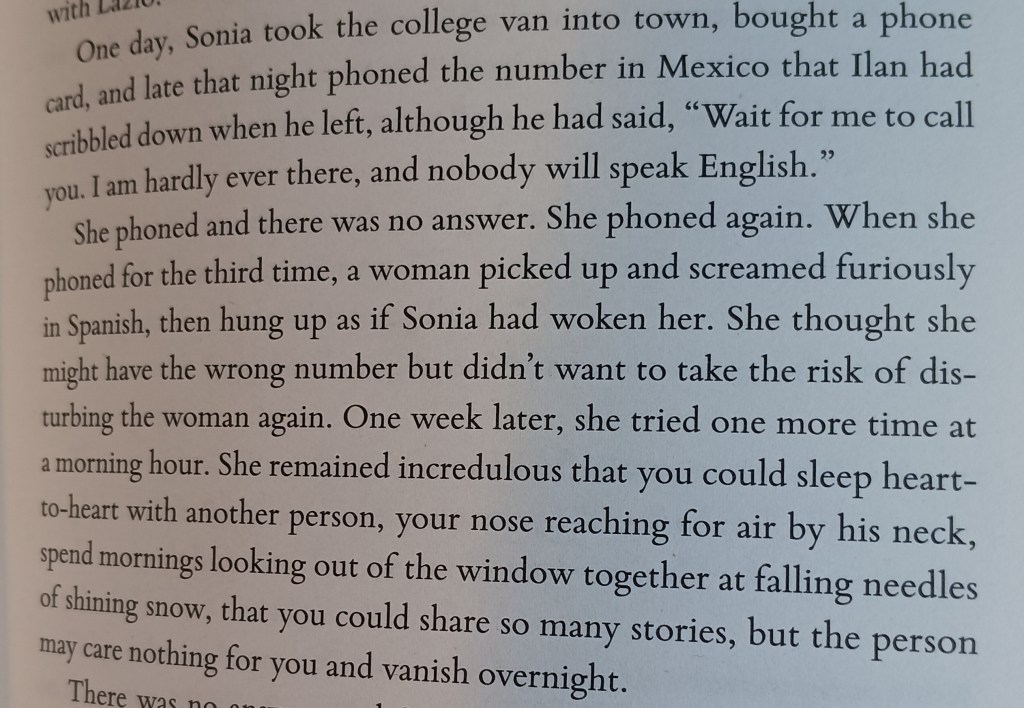

I am currently reading Kiran Desai’s The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny. It is 700 pages long, so it will be some time before I am ready to blog. But I just read this at the end of a chapter. Sonia – horribly lonely, having been left over the winter at her college in the USA (Vermont) in the snow, a thing she has never seen or felt before, forms a relationship with an East European origin neurotic artist, Ilan, who goes away one day, leaving no easy contacts. We get this:

I find the last sentence of the last paragraph simply heartbreaking, triggering all kinds of memories of folly-bound relationships with people not even a neighbour, but also turning nearness into something you sense when at your most lonely – when the fundamental barriers between separate selves are felt most, whether they apply to the thoughts prompting those feelings or not.

All from me today

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxx