What is the worst that might happen? Is it the fear of failure or to hope that you might eventually fail, and to dread failing to fail.

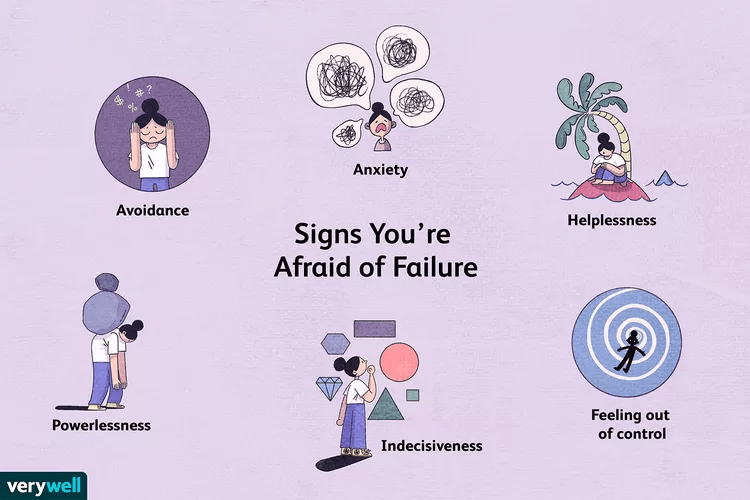

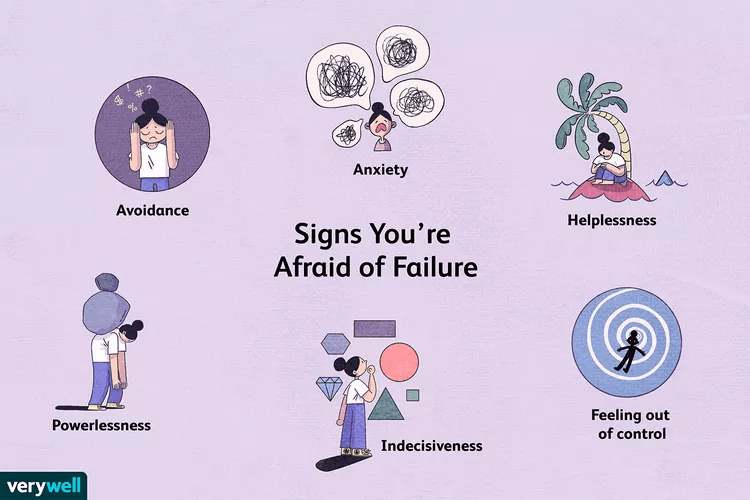

An infographic from Verywell Mind website detailing the signs and symptoms of a ‘fear of failure’: https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-the-fear-of-failure-5176202

The title I give this blog may sound like nonsense? No doubt it isn’t the first time I have invented such a title, nor will it be the last! You might read it and ask? Does anyone prefer failure to succeeding? Under what conditions or in what circumstances would it be preferable to fail than succeed? We know why we have ‘fear of failure’, but why a ‘fear of success’?

But the poet Robert Browning certainly continually imagined situations where failure seemed the goal of one’s appointed work in the world – such as in the painter Andrea Del Sarto in the eponymous dramatic dialogue representing him as its chief character and speaker. And most tellingly there is Childe Roland, the medieval night in the poem, Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came. Here are the key lines where Roland explains himself, as he turns towards what has been pointed out to him as the place where his wanderings might come to an end and his fitness for his task be finally tested:

3. ...

I did turn as he pointed; neither pride

Nor hope rekindling at the end descried,

So much as gladness that some end might be.

4.

For, what with my whole world-wide wandering,

What with my search drawn out thro' years, my hope

Dwindled into a ghost not fit to cope

With that obstreperous joy success would bring,—

I hardly tried now to rebuke the spring

My heart made, finding failure in its scope.

By this time, he seems to me to say; ‘I have sought my goal so long and so far, in time and space respectively, that just having my search end will be enough for me?’ This indifference to either success or failure as he nears the end of his quest though deepens as he wonders if psychologically his capacity to hope has turned into a weakness that might find success overwhelming. ‘Obstreperous joy’ in success may finally end his life, for his heart is weak, both physically and as a metaphor for his emotional stores. There is such lassitude here that he can not even stop himself feeling joy, dangerous to him as we know, even in ‘finding failure in its scope’.

For him, failure is not just as viable as success as the end he seeks (needing his wandering to end) but the end he prefers. Indeed, he has convinced himself that this is the end he has all along been seeking. Let’s try and feed that into a response to the prompt question, inverting its interrogative into a positive answer:

I would attempt to fail provided it was guaranteed I didn’t fail at failing too; in the worst instance, succeeding in a task where I tried to fail.

Note that you might fail at failing in a task in this formulation without actually succeeding in doing anything at all. I am imagining here shades of feelings of failure that are hard to pin down for they are not the antithesis, or binary opposite, of success exactly but an experience that I want – that feeds something in me and allows it to flourish in a scheme of things not tied down by the binaries of success and failure. There is something in failure then that promises complete rest from the aim of trying to succeed, for success in one aim just prompts the need for further conquests to prove the virtue of success on and on, again and again … where some kinds of failure ensure you are set no new tasks at all, but instead find a destiny that does not prompt ongoing agency to reach a new height higher than the last but satisfies itself with ‘gladness that some end might be’; a sense of a life completed, not forever seeking to fulfil its unfulfilled destiny onwards and upwards.

By the way, from now on in this blog I will quote huge chunks from a long epic poem by Edmund Spenser, just to show what a travesty it is that the teaching of English literature rarely these days, even in universities, includes Spenser. I often thought the secret of Browning’s Childe Roland was my favourite canto 9 from Book 1 of Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (see this link – the spelling is as in the published work), wherein as we shall many knights have gathered together and each given up success forever in future tasks by failing to fail and come to terms with it and instead have completed their self-harm in self-inflicted death (suicide).

The Red-Cross Knight (St. George for England of course) is traveling with Una (unity in religion and state) and meets the knight Sir Trevisan fleeing a great evil behind him, bare-headed (without a helmet to complete his armour) and with a rope around his neck. Trevisan had visited the cave of Suicidal Despair and tells a tale of how he with and another knight, called a ‘faire knight’, a lover have visited Despair. Despair seems much interested in manly men of arms, especially in couples, and ‘creeping close‘ to them like the Serpent to Eve in the Garden of Eden, he seems to enter them subtly. So who is Despair?

A man of hell, that cals himselfe Despaire:

Who first us greets, and after faire areedes 250

Of tydings strange, and of adventures rare:

So creeping close, as Snake in hidden weedes,

Inquireth of our states, and of our knightly deedes.

XXIX

Which when he knew, and felt our feeble harts

Embost with bale, and bitter byting griefe, 255

Which love had launched with his deadly darts,

With wounding words and termes of foule repriefe,

He pluckt from us all hope of due reliefe,

That earst us held in love of lingring life;

Then hopelesse hartlesse, gan the cunning thiefe 260

Perswade us die, to stint all further strife:

To me he lent this rope, to him a rustie knife.

But how like Browning’s Childe Roland is the effect on Trevisan and his comrade. What Despair finds underneath the tales of daring-do that the two knights tell is that same weariness of forever pursuing an end that gets no nearer – a final thing we call success, and with it completion. Spenser imagines that sidling creature coming close to outwardly tough men so that, Trevisan says, he can have ‘felt our feeble harts’ (an early version I believe of Whitman’s ‘dear love of comrades’). From thence, he persuades them that in seeking successive successes, there can never be ‘due reliefe’, and thus to instead ‘stint all further strife’.

I need to quote these lines to ask anyone who reads them here to delight in how Spenser uses his final rhyming couplets in his stanzas (always called Spenserian stanzas and with an a,b, a, b, b, c, b, c, c line-ending rhyme scheme) that use the rhyme between a line lasting ten syllables (an iambic pentameter) with one lasting twelve syllables (an iambic hexameter) to comic emotional effect. These lines bring out the humorous bathos of Despair and the very vulnerable ‘faire kight’ (the softer of the two) seeing an end in something so banal as a ‘rustie knife’. These comic effects are what make Spenser important as a poet and always make me wonder whether Milton himself was having a laugh when he called him ‘sage and serious Spenser’.

Trevisan, having escaped whilst his mate succumbs to the ‘rustie knife’, urges the Red-Cross Knight not to confront the cunning softly voiced Tempter but to flee. Suddenly, we see something more of what Despair represents as a character – he represents the art that lies in soft and soothing words offering a quick fix to doing your proper work in the world. Una believes that Red-Cross needs to confront such temptation, such art’, and Redcross complies:

XXXII Certes (said he) hence shall I never rest, 281 Till I that treacherours art have heard and tride;

There is nothing, Red-cross insists herein, that I cannot turn into a trial in which I aim to succeed and in which I dare not fail. Thence, they all go to the Cave of Despair, Trevisan guiding but fearful to go in on arrival, without Red-cross to front him, as he fronted the ‘faire knight’. The cave is a Gothic scene, noted for its lack of fertility – totally barren, a place where men do not sow seed but give up instead their ‘carcases’ in general piled array.

XXXIV

And all about old stockes and stubs of trees,

Whereon nor fruit nor leafe was ever seene, 300

Did hang upon the ragged rocky knees;

On which had many wretches hanged beene,

Whose carcases were scattered on the greene,

And throwne about the clifts. Arrived there,

That bare-head knight for dread and dolefull teene, 305

Would faine have fled, ne durst approchen neare,

But th' other forst him stay, and comforted in feare.

And though he ‘comforted’ Trevisan’ Red-Cross goes into the fray as if nothing could harm him, especially someone testing the endurance of his willingness to stand up as a man of courage. But Despair turns on Red-Cross the same tools as formerly to Trevisan, arguing that all that man-talk (‘great battels, which thou boast to win’) about always succeeding is so much rot – the more you seek to succeed the more you’d accrue error too, to proceed in ever accumulating cost to the life of others, the ‘losers’, the more you will see that sometimes failure might have been best – for in success on sucess we have ‘missed the way’ (the etymology via Latin and French of ‘error’):

error (n.) : (also, through 18c., errour😉 c. 1300, “a deviation from truth made through ignorance or inadvertence, a mistake,” also “offense against morality or justice; transgression, wrong-doing, sin;” from Old French error “mistake, flaw, defect, heresy,” from Latin errorem (nominative error) “a wandering, straying, a going astray; meandering; doubt, uncertainty;” also “a figurative going astray, mistake,” from errare “to wander; to err” (see err). From early 14c. as “state of believing or practicing what is false or heretical; false opinion or belief, heresy.” From late 14c. as “deviation from what is normal; abnormality, aberration.” From 1726 as “difference between observed value and true value.”

To this etymology Spenser chimes his verse: ‘sin’ rhymes with ‘win’, the ‘right way’ rhymes with ‘stray’ that is carried on as the first rhyme of the next stanza (XLIV – 44):

XLIII

The lenger life, I wote the greater sin, 380

The greater sin, the greater punishment:

All those great battels, which thou boasts to win,

Through strife, and blood-shed, and avengement,

Now praysd, hereafter deare thou shalt repent:

For life must life, and blood must blood repay. 385

Is not enough thy evill life forespent?

For he that once hath missed the right way,

The further he doth goe, the further he doth stray.

XLIV

Then do no further goe, no further stray,

But here lie downe, and to thy rest betake, 390

Th' ill to prevent, that life ensewen may.

For what hath life, that may it loved make,

And gives not rather cause it to forsake?

Feare, sicknesse, age, losse, labour, sorrow, strife,

Paine, hunger, cold, that makes the hart to quake; 395

And ever fickle fortune rageth rife,

All which, and thousands mo do make a loathsome life.

XLV

Thou wretched man, of death hast greatest need,

If in true ballance thou wilt weigh thy state:

For never knight, that dared warlike deede, 400

More lucklesse disaventures did amate:

Witnesse the dungeon deepe, wherein of late

Thy life shut up, for death so oft did call;

And though good lucke prolonged hath thy date,

Yet death then would the like mishaps forestall, 405

Into the which hereafter thou maiest happen fall.

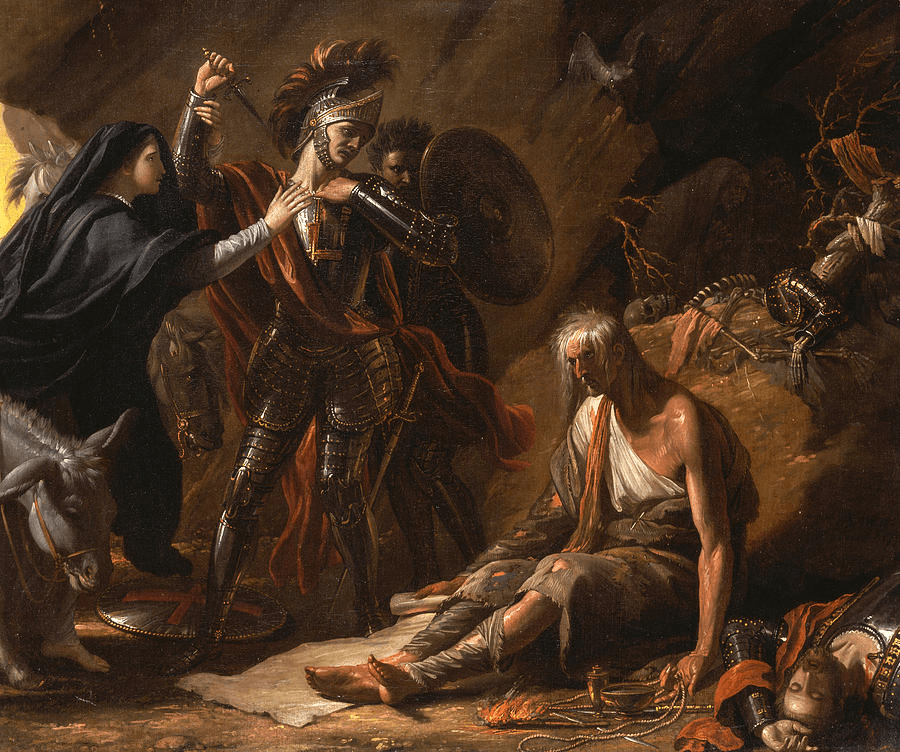

After this Red-Cross takes the proffered dagger to his own neck, as pictured below, with Una running to protect, Trevisan still masked behind Red-Cross. The lover with the ‘rustie knife’ at his neck lies to Despair’s left (our right).

But supported as he is, Red-Cross escapes and leav⁸es Despair to consume his own philosophy of Despair, that of failing to ever meet the strictures of his own arguments. The final stanza is the most wonderful one in this Canto and Book One, as Despair sees Red-Cross (‘his guest’) depart, he decides to kill himself only to realise that he can never succeed and thus never fail – he can only fail to fail and fail to succeed. His action is cyclical, ever repeating the fate of the despairing (‘hung himselfe, unbid unblest’) cyclically never to ‘doe him die’ until despair dies when all worldly things die in the eternity of the Final Revelation of truth. But this cyclical ‘failing to fail’ has a kind of music to it, as ‘die’ resounds with ‘die’ and rhymes with the final syllable of ‘eternall-eye’, as it was then pronounced in that final extended line.

LIV So up he rose, and thence amounted streight. Which when the carle beheld, and saw his guest 480 Would safe depart for all his subtill sleight, He chose an halter from among the rest, And with it hung himselfe, unbid unblest. But death he could not worke himselfe thereby; For thousand times he so himselfe had drest, 485 Yet nathelesse it could not doe him die, Till he should die his last, that is, eternally.

And this is a type of image that Browning resets, I believe with only my feelings to guide me, at the end of his poem, as his Roland realises he has played the same game as all his past peers, who have all now come to view the ‘last of him’, a lasting end they didn’t achieve himself because he only blows his horn and starts the poem again, its title also its last line, and thus its first: ‘Yet natheless it could not doe him die’.

34.

There they stood, ranged along the hill-sides—met

To view the last of me, a living frame

For one more picture! in a sheet of flame

I saw them and I knew them all. And yet

Dauntless the slug-horn to my lips I set

And blew. "Childe Roland to the Dark Tower came."

And note that, just as meeting Despair is confronting his ‘treacherous art’, so is Childe Roland arriving at the Dark Tower: it makes him art that never dies because it keeps on being repeated in the gaze of each new reader, or viewer of ‘a living frame / For one more picture!’. What were the signs of fear of failure (look again below): avoidance, anxiety, helplessness, powerlessness, indecisiveness, feeling out of control. But these are the behaviours of Despair and Childe Roland – they are the reason we have art, for in truth we control nothing, not even death – which is never the statement various notes left behind mean it to be, but just signs of fear of failing at failing and being ever nuanced.

There are worse fates. Stay alive with me as long as we can. It is so much more interesting eventually, if only cyclically, for to fail periodically is to emphasise that there is a higher power than one’s own ego, as Alcoholics Anonymous always knew.

Bye for now

Love Steven xxxxxxxxxx