Though I do not, some queer people need God to validate their being and their capacity for love! It has taken me decades to understand and accept that. This is a blog on Harry Tanner (2025) The Queer Thing About Sin: Why the West Came to Hate Queer Love, London, Bloomsbury Continuum. It’s a book about a lot more than than that, however.

Dr Harry James Tanner is, it appears, a freelance scholar – not hampered by institutional definition by a university – as well as an attractive young Irishman. The independence of his scholarship from academic bondage to any one theory (even queer theory) for this book is more personal than to which queer theory lends credence – and, moreover, uses the word ‘homosexual’ as if it had more than meaningful content than as a concept situated in late Western European psychiatric thought, though loosely as if it might mean merely ‘men who have sex with men’.

However, whilst being truly scholarly, his debut book shows, in its readable style and generosity of address, even in its almost missionary tone of explaining g a problem in the history of Western Christianity, and its formative concepts in the Ancient worlds it succeeded. It’s called The Queer Thing About Sin: Why the West Came to Hate Queer Love. No book is mentioned within rhis one that is not fully explained and then contextualised according to the needs of his argument, but also with respect to its author’s possible and probable intentions.

But here’s the rub: Harry Tanner wants and needs God again now as an adult as much as he did as a teenager scarred by the Evangelical Protestantism he inherited and his book is premised on the view that God loves people who loves and has loving sex with other people, and that it is possible to explain why so many people believe that it is not the case. Indeed, as the book shows queer sex has in the Western world been equated with sin, at its most heinous, but that that view of is a highly nuanced one relating to the economies of persons, families, groups, societies, nations and supranational institutional groupings such as Churches, from Byzantine Christianity to the most splintered of ecumenical organisations.

The point of joining what I have to say about this beautiful book to the prompt question is that it surprises me that I even wanted to read it, for I have given up belief and even the want fo believe in God or Gods, spiritual, rather than human redemption and, perhaps first to go, was any relatipnship to the peculiar concept of Sin. Sin, when personified, and certainly in Milton, is always a woman, though a woman carnal as animals are carnal – more symbolised by liminal fantasy than the feel of a real body. No doubt Milton’s Sin in Paradise Lost with snakes guarding its lower half owes much to Edmund Spenser. Milton imagines her having sex with Satan to give birth to Death. All three personified allegorical figures were painted dramatically by William Hogarth, at the point when both male persons bristle with the pricking of deadly weapons, stopped only by industence to Satan that he is bearing arms against his son:

Consciousness of sin, of course, was part of my psychosocial growth development – how could it be avoided – even if not insistently so from family, vehemently so through Church Sunday school, institutional early education, and general culture (the latter in watered down forms). Like most shadow remnants of old structures of more intense feeling in our predecessors, the shadow persists to validate the ‘reality’ of the paradigm casting it. Perhaps its lack of grip on my working class family is what saved me from really taking Sin seriously as a concept, though I would not say the same of ‘evil’ and suffering as some did – such as Tanner in his reference to his teenage Evangelical Christian beliefs. Tanner’s father was a pastor and beloved; through their mutual love, he absorbed the guilt that focused on the fact that some behaviours, thoughts, values, and feelings were not just unhelpful but sinful, and a denial of God’s intention. He dropped Sin from his life at university, as a result of immersion in archaic, classical and New Testament Greek, and the access that gave him to the multivariate interpretations possible of Ancient texts of all Ancient cultures; multivariance found in the smallest units of language upwards to the genre and material form they take, with the cultural additions born of all these.

However it does it, this book represents a path of return to the concept of a loving God but a path built out of a convincing explanation as to why Ancient cultures might err in determining that sex between people of the same sex/gender was so much the worst of all Sins that even Dante’s Lucifer finds it abhorrent, even if Dante’s readers feel empathy for some of those sinning in that manner.

The examples I give above are not those used by Tanner. His take is entirely original, where mine above is not – he re-reads some of the great texts not only of art, drama and other literature but products of thought covering many disciplines from philosophy, politics. economics, psychology, and history, as well as, of course, the criss-crossing of these disciplines with theology and the business of the administration of ecumenical governance. And the reason for the innovation of his approach, certainly in terms of the Gay Liberation reading of history that I was brought to believe in the 1970s and 1980s was that the villain of the piece is no longer the Western Judaeo-Christian tradition, though Pauline theology remains a possible major enemy of non-reproductive body pleasure, if some of Tanner’s more subtle approaches to these texts, down to the minutest detail, are not given credence. This sentence feels crucial:

Gay sex had become, thanks to the work of generations of Greek and Roman philosophers, a sign of disordered nature. [1]

Of course,’disordered nature’ is not the necessary and sufficient condition of ‘sin’ nor does it necessarily contradict the will of the God’s, since they themselves sourced stories of both gay love, sex, and even paedophilic ‘rape’ in the case of Zeus’s abduction of Ganymede. The Gods understood desire and the variety of combinations of objects and subjects of desire involved, but the fulfillment of desire, without regard to consequences is precisely what humans feared would happen if desire led to a eastern of mortal resources, precisely because the were mortal and not, like the Gods, immortal with resources of time, energy and space without limitation. Of the sequelae of this (cultures afraid of excessive expenditure and debt, fear of debt’s consequences and the need for self-control, I will deal with later. This is because, despite the fact that they are inherited by Greek leaning Christianity, and thereafter Christianity generally, these are themes directly found in Archaic, Classical and Hellenic Greece, the Roman Empire as well as indirectly in Post-Ancient worldviews after the waning of Greek hegemony of thought. These ideas fuel the way sin is interpreted in Christianity, though they did not emerge from thought about it(its analogies being largely matters of accident, as in the story of Pandora).

In the Judaeo-Christian model course a ‘disordered nature’ was precisely the consequence of the Fall. It was this that made it necessary to watch for its continuing effects in the nature they lived in and which they manifested in themselves for its deviations from God’s original intentions for humankind who did not know sin, and how it differed from an established order. This was the means of entry into Christian thought of the thought in the Classical world about dealing with human responsibility for scarce resources. One of the funniest versions of the idea of a postlapsarian need for human watchfulness over the excesses possible in nature is in a story told by Tanner as deriving from contemporaries of St. Augustine that insisted that in prelapsarian nature:

Spontaneous erections could never take place in paradise. … This ‘perfect’ world was shattered when adam and Eve ate the Forbidden fruit, … Thereafter, man lost power over the penis and it began to rule him. [2]

We must return to this world where sins of the body were an effect of nature that no longer worked to God’s plan, in the eyes of medieval clerics at leas, later, but the key idea to get about Tanner is about how it was that sin tied itself to gay sex in particular, if not exclusively, and that Tanner insists as we have seen lay in accidents in the history of the Ancient World. In that world, Tanner seeks to discover what are the possible causes of the exception taken by complex social organisations to gay sex, when there is no concept of original sin to account for it, over the course of his history-telling in largely chronological sequence (if we discount the leaps back necessitated when Christianity brought with it to the West, the combinations of history and myth in the Old Testament, the Jewish texts of their faith). Though Immortal Gods could make space , time and resources inconsequential because they are immortal and potent over nature, Mortal humans worked with nature, asserting rule over its excesses – in the animal and vegetable domain too – by managing its scarce (and death-bound) resources with some sense of prudent economy.

Of course I concentrate this argument in one place from a mere serial expression of it in tanner’s beautiful book, which thereby has a readability I cannot aspire to in this commentary based on the needs of my own learning. However, it seems to me that Tanner tells us, over the continuous stories he tells, that the Ancient World employed a combination of networked and interactive ideas, or more accurately schemas, of patterned thought, feeling and action scripts to understand the vulnerability they felt in the face of a nature that must be ordered by some body (whether an individual person, human group or divinity in its more human-friendly mode) if it is to be ordered at all. The things that militated against natural scarcity were patterns of excessive use and / or waste of these resources, all of which can be prompted in the very nature of mortals as immoderate appetites for things that are necessary but also are pleasurable. Let’s spell out in a list – so unlike Tanner’s lovely prose – what these elements of mental schemas involved set out as themes (for all of these themes are associated – and perhaps causally connected Tanner implies – to times when Ancient societies varied from well-evidenced acceptance that sex between people of the same sex/gender was not only tolerable but clearly understood by everyone as a legitimate human fulfillment of natural desire. The necessary and sufficient condition for the triggering of these schemas is the existence of marked inequalities of income, power and accumulated wealth and the prevalence of debt accrued by those attempting to meet their needs.

- First, there must be a perception of the issue of debt as being caused by waste and excess consumption by those unable to afford these things that over-rides the important fact of inequalities that fuel it, amongst those with sufficient resources. This must be so whatever the real cause of an economy based on debt. Secondly, there may be a perception amongst those with few resources that those who do have those resources consume them themselves to excess and without consideration of the needs of other but themselves. In both case greed and excessive appetite comes to be the reason given for failure to thrive, or for failure.

- There is a general fear and anxiety of the consequences of debt, not just in terms of distress at wastage or the ill-effects of over-consumption, but of the possibility of slavery should a person or family fail to meet their debts and have nothing to sell but themselves and their former right to paid employment.

- The necessity of a strategy targeted against the fear of fear of excess and its consequences that is rooted in the concept of self-control.

Tanner everywhere implies these conditions as being seen as analogous and symbolised by sexual excess, of which sex between people of the same sex/gender is the ultimate example or symbol. This applied most strongly to males who were in charge of two important resources, in the view of the period – the wherewithal to father the future with their semen and their role as protectors of the most dependent of family members, and secondly the resources of male hardness sufficient to protect, guard families and nations and fight for the defence of present and acquisition of future resources. The most wasteful action this mind-set is the loss of semen to another man and the softening of masculine hardness in the competition for resources and defence of the necessary soft core of the family and nation – its women and children.

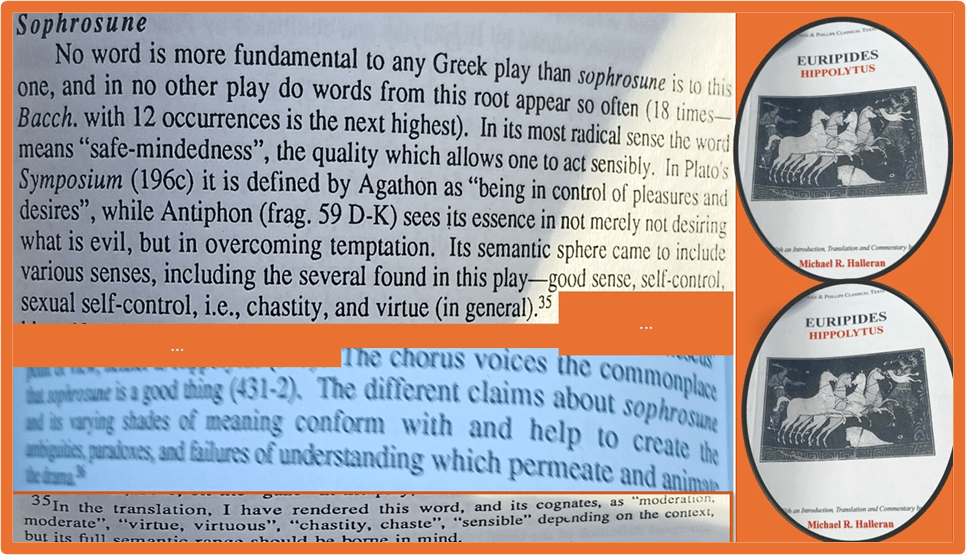

In Greek tragedy, there is a word for self-control, transliterated as sophrusune and it is applied particularly to the problematic young male Hippolytus. According to Michael R. Halleran in his introduction to his parallel Greek-English edition of Hippolytus, it is a word used 18 times therein, in comparison with 13 appearances in The Bacchae, which is the Euripides play Tanner deals with. It is fairly clear that Phaedra’s sexual desire for her young son-in-law shows somewhat of a lack of self-control. Indeed, in order to exert self-control over herself, all Phaedra can do is kill herself. But before doing so, she says that it will help Hippolytus learn that same virtue too, implying his desire to stay narcissistically as a boy amongst boys also lacks self-control. The words in Greek which suggest that both are equally lacking in self-control are:

Κοιν̃ηι μεταϲχ̀ων ϲωρονε̃ιν μαθ́ηϲεται. ('in common with me he will learn to be moderate {sophron}) [5]

Halleran, whose translation I use above, develops the issue around sophrune more in the passage below from his introduction from the play: [6]

What this emphasises with Tanner’s more excitingly written and contextualised examples (which need to be read and enjoyed) is that the stress on sophrunuse in Greek culture (Tanner just says simply ‘self-control’) may have had as much sway on creating a negative attitude to gay sex – to seeing it as the most uncontrolled, unregulated, wasteful and excessive of behaviours, in Euripides Bacchae it is the very essence of the Bacchic (see if you wish my blog on this play recently at this link. It refers to this book warmly too).

I state all this far too crudely but that interpretation, which I do that in order to stress, seems to what this book implies in pursuing the association between negative attitudes towards sex between men in particular and the wider political economy of families and nations in times of actual or believed scarcity. In classical times, Tanner traces these associations to various places in time and space – in Sparta for instance, Athens after the drain of resources caused by the Peloponesian War and the Roman Empire. [3] In none of these cases was there not a continuation of queer behaviour that continued alongside a public, and sometimes hypocritical, theorisation of it as the extreme of excess and the sign of poor self-control in an individual, city, nation or other group. Moreover, in the height of the prosperity of the city state of Athens, and its hinterlands, called collectively Attica there was the reverse not only of the conditions we have seen as primarily psychological reactions to the economy and the prevalence of debt, but also positive belief in the beauty and truth embodied by queer partners according to Tanner. It was in the failure of wealth finding its way back from the settler colonies, harvest failures and the depression of the silver market and production in Attica that reproduced there the conditions of Sparta, represented in writing by Xenophon’s Oeconomicus, the only substantial surviving work by a philosopher of the political economy of scarcity, but representing many such works that have been lost. [4]

When Tanner looks for Christian or post-Christian examples of excess, coupled somehow – and sometimes quite without perceptible reason – to gay sex. For example, famine in Palestine just preceding the birth of Christ and the continuing prevalence of a people ‘desperately poor, indebted, underfed, unemployed and burdened by an oppressive dual taxation system from Rome and the Jewish authorities’, unleashed a rebellious spirit and a whole group of popular moralists, also often miracle-workers and very much like some aspects of Jesus’ mission and also preaching an Armageddon, accusing rulers of excessive appetite that was feeding off the poor as reported by the later Christian writer, Origen [8]. The sin was interpreted in terms of the economic and rulers were accused particularly of licence that easily fitted, they thought, to the license leading to sodomy. But the sin and the clampdown on queerness is generalised to everyone in every class. Tanner finds another example from the way revolutionary moralists looked at the aristocracy focused around the palace of Versailles in the eighteenth century, for whom the Ancien Régime was aptly represented, A notorious party in July 1722 scandalized everyone, but the reaction of bourgeois moralists was to seek out the sin not amongst the aristocracy but the profligates they believed to be meeting for sex in the Jardins des Tuileries and police were posted there as agent provocateurs , apparently seeking sex but locking anyone who responded to them in the Bastille. [9]

I could pick out so many instances of clever re-readings of history that make the case that the characterisation of gay sex was primarily based on the feeling that it was par excellence, a failure of self-control, but the book does so much more than that, but one very interesting application of that idea is to show that St. Paul may have inherited his fervour against gay sex from his immersion in Hellenist period Greek culture, as well as Judaic, thought and that the former source may have been most influential in this regard. Tanner describes him as ‘steeped in Stoic and Platonic teaching, and was implacably opposed to all sex’. [10] He cites a lesson that could well be one given by Zeno the Stoic. [11] It is from I Thessalonians:

“[You must] hold yourselves from sexual immorality, everyone of you [must] know [how to] control your own body in accordance with holiness and honour'” [cited 10, again]

It is hard to say enough to show how rich this book is, but my aim anyway is not to do that but to show how the book relates to me ‘having changed my mind’ (as per the prompt question) about other people’s professed need for God. This book is a generous book. It is aimed at queer people who need explanation of. why they need not feel God ‘hates’ them unless they hide or subdue their queerness. His book intends to look at why when gay rights appear to have become established, they can in times of economic and social crisis, like that upon us now, they can be attacked again. His aim is particularly to arm those needing God with foreknowledge that armours them and helps to deal with the ideologies now beginning to spring down upon us again from the political right in USA and UK:

In understanding the connection between these crises and the rise of political ideologies that target queer people, we have more chance of understanding where this hatred came from, noting it and stepping over it. [12]

But what is beautiful do is the means by which Tanner begins a potential ideological cleansing of the Christian tradition, making it less unfriendly in its face towards us a community, and addressing those misconceptions about ourselves – also often taken from Greek culture – that have been used to persuade us that we are rightly targeted – the belief for instance in the stereotype of the predatory older queer male feeding off innocent youth. Let’s look at how he does this last thing first, and perhaps why he does it.I end with asking why he does it because it was often in the days of GLF (Gay Liberation Front) and GAA ( Gay Activists Alliance) thought to be a mistake to address false accusations made about queer people in general based on false stereotypes. One such stereotype was that of the person attracted only to children regardless of consent and the validity of that consent.

Yet as Tanner shows the pantheon of gay martyrs and heroes include people who themselves were ready to peddle such stereotypes and to naturalised them by using the example Greek homo-eroticism, not least John Dover Wilson in his classic text Greek Homosexuality. And at the root of the misunderstanding peddled by Wilson was the same myth of universal pederasty supposed to be the proven nature of male queer love in Greek life and literature (and one emphasised by Oscar Wilde perhaps for reasons that were not as pure as he presented, Tanner argues), despite the fact that Homer’ s example of the love between Achilles and Patroclus was not one between man and boy. Tanner addresses first the linked error about the nature of Greek male to male love once implied as universal (amongst participating males at least) and the continuation of a stereotype allied to notions of the rape of minors, which Tanner rightly condemns. One of his methods of doing so is characteristic. It queries the interpretations of particular words both in their original texts, for he does the same with the Hebrew Old Testament, the Greek New Testament and even the Ancient Sumerian epic Gilgamesh (for my blog on this see this link). But he sees other problems here, such as the troubled meaning of the usages of the term ‘boy’ in queer context, often carrying assumptions of tenderness in some cases as adult men consider their beloved in the stereotype of youth or od power – and certainly most queer relationships in Classical literature bear this power differential, even Achilles and Patroclus as Aeschylus’ play The Myrmidons supposedly emphasises. But the relationship is not therefore seen as based on control – as is emphasised in the poetry whereof Theognis, who calls his lover pais (which can mean ‘boy’) but shows their demands to be the dominant not the subordinate ones. [13]

But the best queries on words do wonderful things in making us question assumptions about historical beings, or people presented as such – for Tanner admits that the evidence for a historical Jesus is far from rooted in solid evidence – use of words and text genres to prove that their supposed antagonism to queer people may be ill founded. There is a beautiful section of the book that shows that the evidence, read properly, may show Jesus himself to be an ally of queer men. The section on this is fascinating, not least the role of the Church Fathers in removing any claim to canonical status of a version of the Gospel of Mark promoted by the Carpocratians, wherein Christ raises a young man from the dead and sleeps with him on the night of his rising. However, best of all is the discussion of ambiguous Greek terms in the canonical New Testament. In a passage at the root of the notion of the dogma of priestly celibacy, Jesus uses the word eunochoi, which Tanner argues may refer to a group of people exempt from proving their worth as Christians by only having sex with their wives [14]. Tanner makes no commitment other than saying ‘had the writers of the of the Gospels and Jesus himself wanted to give the impression they were staunchly opposed to queer identities, this is a very difficult to explain’ (read it for yourself in the book). [14]

And even more amazing are those discussions in the book of Pauline theology that express the possibility that even St. Paul might, as some Christians hope, have been less virulently homophobic than thought. There are two parts of the argument that stand out for me. First the discussion of Paul’s Greek terminology usually thought to relate to queer men in the list of those ‘unrighteous’ who will not ‘inherit the kingdom of God’. These words are (transliterated) malikoi (usually thought to translate as ‘soft men’) and the unfortunate Greek term, arsenokoitai. Neither are easy to translate but Tanner niftily shows not only why it is likely that the latter term means ‘men who have sex with men’ but cleverly suggests that it refers to the men who were ‘tops’ (ready to fuck any hole) given that ‘soft men’ is likely o refer to bottoms – passive sexual partners. So Paul is not redeemed here, thought some Christians want this. Tanner does not give in. His next argument is that the text in which Paul speaks this is in fact dialogicand that he answers those who condemn with more tolerance. In showing how the text can be read thus he uses the evidence of how Paul is likely to have written in the same fashion as the texts of Plato, which in dialogue identify no single speaker as that speaker, other than as a assumption from the way the interactors name each other in their speeches. Was Paul actually arguing against homophobes ‘rather than being homophobic himself’ in dialogue form he guesses. The question can’t be decided but were it the case, that ‘would be more logically consistent with Jesus’ position on … queer identities’. [15]

Perhaps there is a degree of special pleading here, but it would be necessary if Christian theology and its sequelae for communities were to be as ‘inclusive’ as some argue it is. As a man without the belief or want for it, It matters not for me, but I am struck by the sadness of humans who need to believe in a living God who cares, mediated by the human voice of a Redeemer and so honour this queer project to give people succour. Those are the people who Browning may have characterised in his wonderful Epistle of Karshish, which ends as the Speaker, Karshish, the ‘Arab physician’ refers back to his correspondent Abib about rumours he has heard of Christ’s mission from a world that has seemed weary, flat and unprofitable to him otherwise:

The very God! think, Abib; dost thou think?

So, the All-Great, were the All-Loving too—

So, through the thunder comes a human voice

Saying, "O heart I made, a heart beats here!

Face, my hands fashioned, see it in myself!

Thou hast no power nor mayst conceive of mine,

But love I gave thee, with myself to love,

And thou must love me who have died for thee!"

The madman saith He said so: it is strange.

The same human impulse that makes me love this – A.S. Byatt when she lectured on the poem when I was a student at UCL said that this was Browning thinking subtly about the view of religion in Feuerbach’s The Essence of Christianity, which derived religion back to the need for a likeness to exist that felt for, and loved, the subject who longed for that love. I think she was right and in this view is an empathy for others who don’t think and feel as I do, or Byatt did, that matters. Harry Tanner addresses this, not least in his treatment of the harshest homophobic church structure that of Byzantium, which still harboured trans monks (and we have the documentary evidence) and had an institution for monks called, in transliterated Greek, adelphopoesis (the making of brothers) – a ceremony like marriage. The discussion on it is subtle, nuanced and beautiful. [16]

That’s all I have to say, but I worry that I have not done Tanner justice. This book springs from a beauty of soul (another concept I reject) and reflection (which I don’t). Read it.

With all my love

Steven xxxxxxx

___________________

[1] Harry Tanner (2025; 178) The Queer Thing About Sin: Why the West Came to Hate Queer Love, London, Bloomsbury Continuum.

[2] ibid: 186f.

[3] See ibid respectively 33f., 55ff (especially on Demosthenes), 133ff.

[4] See ibid 76 – 79.

[5] Euripides (ed, trans Michael R. Halleran) (1995: 103, line 731) Hippolytus Oxford, Aries & Phillips

[6] Michael R. Halleran (1995: 45f.) ‘Introduction “The play”‘ in Euripides ibid.

[8] Harry Tanner, op.cit: 161ff.(quote from 166).

[9] ibid: 196

[10] ibid: 177

[11] ibid: 91ff.

[12] ibid: 202

[13] ibid: 12, see page 33 for The Myrmidons

[14] ibid: see the section from ibid: 171ff., last section 171f, the Carpocratians are on pages 173f. (for the possibility of a mythical Jesus see ibid: 158)

[15] ibid: 179-181

[16] ibid: 189f.