Today’s task ought to be why I want so much to do the blog I plan for tomorrow: the first draft of the start of which in Word I have screenshot above. I wince a bit that it feels necessary for me to pick up what in Damian Barr’s novel is weak in the second paragraph but I promise the rest will be laudatory (it just felt like it needed saying). The novel is about the queer artists, Robert MacBryde and Robert Colqhoun, who.lived as an open couple in London: open that is to sex with other men and known as queer amongst their friendship group and, accidentally, to a Colonel Blimp whose windows across the street on Bedford Street accessed sights in number 22, where the young men lived, and to sights Barr has describing as ‘orgies’.

It is a period in art I love and blog about – notably about people (artists and artist subjects) known to the lads in this book – and sort of figured thinly in it; Peter Watson, Lucien Freud, Francis Bacon, Muriel Belcher, John Minton and Keirh Vaughan, as well as numerous sailors and soldiers ready to exchange sex (as long usually as their role was the ‘male’ one ) for a place to stay overnight in London. But though this attracted me to it at first, I can’t say that this feature of the subject matter kept me reading it because the information in the book about theze collatera lives is less interesting and less the stuff of the kind of truth that fiction ought to deal with.

So why did this book hold me. This is for reasons I want to deal with in the blog and that lie behind the fictive inventions, like the character of Morris, the unauthorised schedules of the lads’ first meeting on the train towards their joint first day at the Glasgow School of Art, the invented letters and so much more circumstantial detail that make it a successful novel and not a lazy form of queer biography.

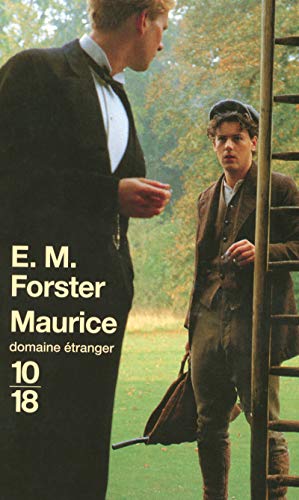

But today, what concerns me is why someone living in the dire times we are when the space for inventive forms of living is shrinking, as witnessed by a novel like the recent Nova Scotia House (for the blog on that use this link), we need to return to the way men who form loving relationships to each other during the forties and fifties of the last century. I think this is because living as a couple was a difficult choice for men even imaginatively, as E. M. Forster showed by the improbability of the escapist ending, either of them as described by an AI engine below summarising material from the variorum Abinger edition of the novel, of his 1914 manuscript eventually published in 1972 as Maurice.

The Original Epilogue (Discarded): Details: In the epilogue, Maurice and Alec Scudder are working as woodcutters many years later.

Plot: Maurice’s sister, Kitty, encounters them, and it is revealed that she is shocked to learn that Maurice has been in a relationship with a working-class man.

Reason for Removal: Forster removed this epilogue after receiving negative feedback from his friends to whom he showed the manuscript.

The Revised Ending: The “Greenwood” Ending: The final version of Maurice ends with Maurice and Alec’s decision to leave for the “greenwood,” a symbolic representation of their commitment to each other outside the constraints of society.

In truth, the unlikelihood of either ending reprezenring social realitiez rarher rhan romantic symbols is as much prompted by consideration of the transgression of boundaries between social classes as the fact that both lovers are men, a factor in the reaction to the heteronormative relationship in D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, too.

The issue about the two artists, both with the first name Robert, was not the relatively minor difference in class status, though Barr makes this matter in the novel where novelists not of working class origin would not have noticed that thwre could be such a difference, but the awareness in borh that to choose to live together was to choose visibility as queer men each emotionally and practically [even if not sexually] committed to the other as much as in more open heterosexual marriages.

Most of the fictional invention of the beautiful first half of the novel is about the fear of detection and the suppression of behaviours that render queer love more visible, audible, or guessable. and makes it very moving. Robert (Barr reserves the name for Colqhoun only) hates it that he is ‘accidentally’ aligned with Bobby (used exclusively for MacBryde) as a result of both being late for their induction into the School of Art. Yet the affinity seems both to stick and become subjectively fixed so that Robert cringes when Bobby touches the cold stone arse of a statue of Saint Sebastisn without caution or shame.

The need not to be seen together, or at least at less than formal distance from each other, let alone decide to set up a sort of ‘home’ together in a rented attic, meditates the transitions of their relationship eventually, negotiated by the acceptance of the ‘fictional’lie’ that they live together as flatmates only, impoverished students at that aiming at finding space for their common role as painters. Should they be seen with girls they ponder – negotiating specific instances with less than open discussion of the reasons that might suggest not? Should Bobby be seen with the very visible cross-dressing Morris and his partner, the latters’ relationship semi-hidden by a common trade interest in The Barras market.

More disturbingly, the men learn that, even at the cost of life, they must neither seek the advice of legal authority or the guardianship provided by their surveillance. Even at the threat of violence and / or death, they learn to run from, rather than confront, the challenge It is for this reason that they mistake Morris for dead when his house and stock-in-trade is violently robbed leaving behind a dead body that they assume to be his, but is not.

At the end of the novel, when the lads’ art tutor, Ian Fleming, and the painter of the most famous portrait of the duo, is consulted after their death he says that they were not ‘homosexual’ in Scotland, though we know from his coded comments in the novel that Barr felt that Fleming knew but would not in public acknowledge the nature of their association. It is a knowledge that speaks out to queer men even in the coded nuance of the portrait, where the young men ‘nearly’ touch each other but not quite and whose facial expression and body language negotiate.mutual desire very differently.

Yet the novel is also very good in showing that coupledom and exclusivity are not synonymous for these early pioneers of living openly together. These inclusions of otherness did not stop at sex since they included relations that felt loving as well as sexual, if at a differing degree, such as that between Robert and John Minton, although the latter’s boundaries were almost non-existent when it czme to male-on-male bonding types. The one story that is told better than I have seen it told before is of the origin, continuance, and memorialising of the couple’s collection of buttons from the uniforms and clothing of men they both formed threesomes with.

My interest in this is deep because it forms part of the joint history of the discusussion of the desirability, viability, and ethics of exclusion in couple relationships. No queer man who had passed the history of the movement both myself and my husband encountered would not have come across characterisation of couple relationships as the goal of all gay love, or at the other extreme, rhe most likely reason of its non-endurance. When we said in the nineteen-sixties that ‘politics is personal’, we debated whether loving bonds would not also be bonds of possession and control rather than of liberation of self and other.

Longer life than we thought has not meant this question is closed for Geoff and me though our commitment to each other has proven absolute. The Two Roberts allows you to feel the tensions in coupledom again as if you were living them in the reading, and, for me, this makes it a valuable, honest, and special book

I am sure my review won’t open the personal side of the memories it helped to be articulated inside me but it is worth knowing that we read for much more than an impersonal appreciation of art, and that perhaps any such impersonal appreciation would be a myth that entirely degraded art to another commodity: a very special commodity, whose values pretend to transcendence perhaps, but a commodity nevertheless. Not for me, please.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxx

One thought on “To work out why I want to do tomorrow’s blog on post war queer coupledom and the ambition to make art matter.”