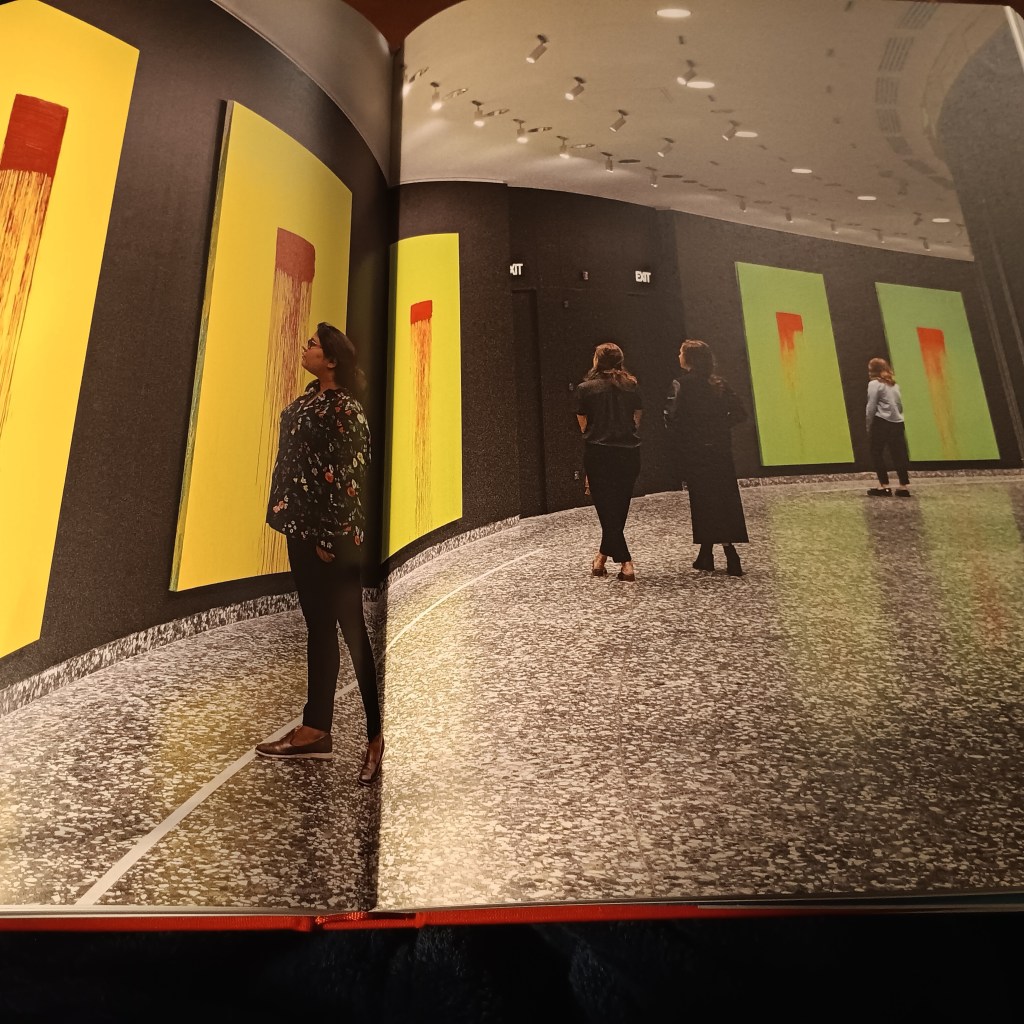

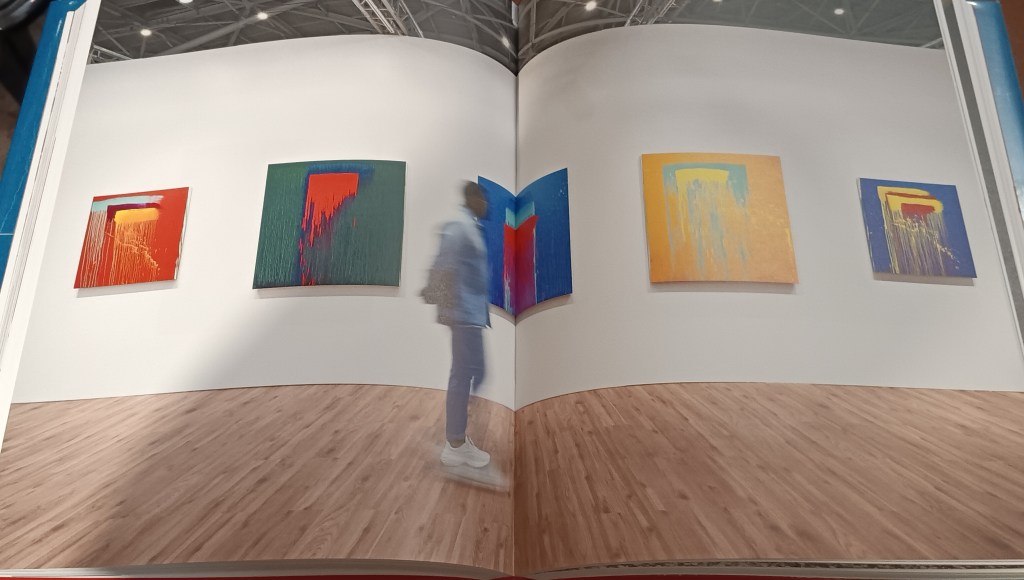

Colour Wheel Exhibition of Pat Steir Paintings at the Hirsghorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D. C. 2019.

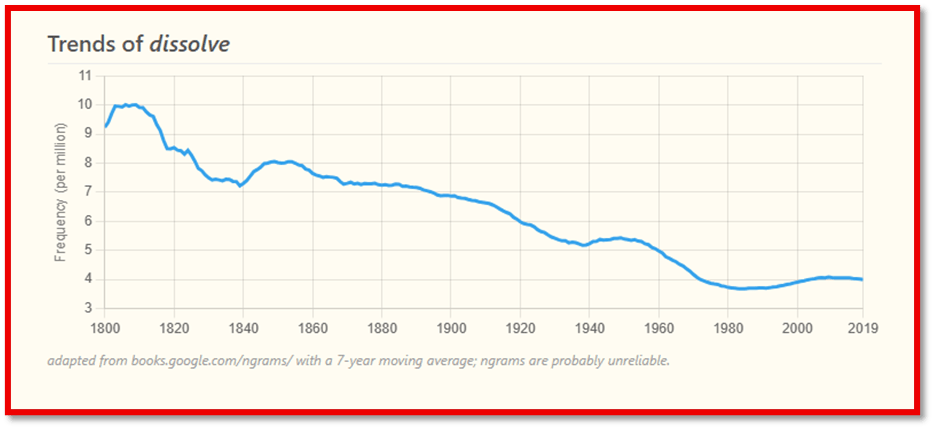

Above is the most telling of n-grams I have ever seen, for it appears (remembering of course that n-grams provide neither valid nor reliable evidence for any hypothesis in scientific terms) that the usage of the word ‘dissolve’, a word I rather favour, has been in decline in printed texts, such as those scanned in Google n-grams, since 1800. I suspect, but cannot verify that this is because the word was once used a great deal in texts aiming at the effects of poetic language, as well as in its major alternative since the fifteenth century to talk of the integrity of institutions under pressure to release their hold on certain function – as, for instance, we refer to in the term in Tudor history for the ‘Dissolution of the Monasteries’. As always etymonline.com serves us well as a guide to meaninmg and etymology, at least in a word like this:

dissolve (v.): late 14c. dissolven, “to break up, disunite, separate into parts” (transitive, of material substances), also “to liquefy by the disintegrating action of a fluid,” also intransitive, “become fluid, be converted from a solid to a liquid state,” from Latin dissolvere “to loosen up, break apart,” from dis- “apart” (see dis-) + solvere “to loosen, untie,” from PIE *se-lu-, from reflexive pronoun *s(w)e- (see idiom) + root *leu- “to loosen, divide, cut apart.” General sense of “to melt, liquefy by means of heat or moisture” is from late 14c. Meaning “to disband” (a parliament or an assembly) is attested from early 15c. Related: Dissolved; dissolving.

Now, in this respect, we only hear of parliaments get dissolved but this usually part of a routine of kinds unlike the Parliaments dissolved by Charles I that led to his fall to the forces of democracy in the Civil War. We don’t hear of it as a national drama much until weaponised by Boris Johnson to ensure the breakup of the bonds that held Britain together in alliance with the European Union by robbing Parliament of the power to divert from that dreadful outcome. From 1800, I suspect the major alternative use for the word was particularly in sciences to describe the process of turning any solid matter into a solution by dissolving it. I suspect that by then invoking the wish that the solid world or its harsh and unyielding laws of being or unavoidable but difficult ideas prompted by a hard world dissolve into something softer is no longer thought an attractive idea.

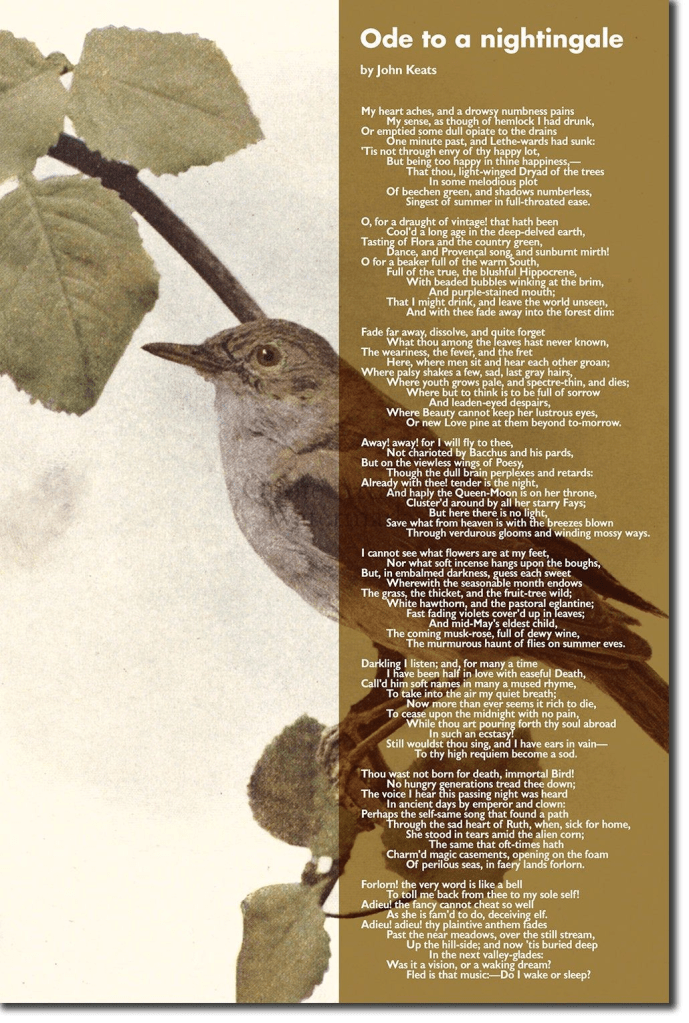

In 1819, the experience of desired dissolution of every fact about a world too hard for one or indeed all was popular enough for Keats to put it at the centre of his great Ode On A Nightingale:

....

That I might drink, and leave the world unseen,

And with thee fade away into the forest dim:

Fade far away, dissolve, and quite forget

What thou among the leaves hast never known,

The weariness, the fever, and the fret

Here, where men sit and hear each other groan;

Where palsy shakes a few, sad, last gray hairs,

Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies;

Taken on its own, the use of drink is not seen as related to the ‘hemlock’ by which Keats invites himself to drink as a means of suicide, but seems the recourse of the romantic addict – like that of De Quincey as an opium-eater, or indeed Samuel Taylor Coleridge. To dissolve merges into suggestions of disappearance – even the play on the word ‘;leave’ in ‘leave the world unseen’ and the ‘leaves’ of the trees amongst whom the nightingale flies to momentarily rest on an available tree branch. What it leaves behind is solidly visceral human experience of aging, sickness, over-labour at a task from which one is alienated. But Keats surely took this from what was his most common source, Shakespeare. Hamlet does not use the word ‘dissolve but implies it in its rhyme assonance and chiming meaning with the word ‘resolve’ when he asks that his ‘too too solid flesh’ might ‘melt’. But when Prospero in The Tempest sees his future son-in-law Ferdinand troubled by a masque created by Prospero on purpose to disturb Ferdinand and remind him that the world he comes from is a world of hard and vile politics.

Having shown the masque Prospero is as troubled if not more so by what he has done and the effect of seeing it himself, and tries to make light of the ‘art’ he uses as something that lacks any solid purpose or reality. The lines are often taken to be meta-critical commentary by Shakespeare on his own art such that when Prospero sees a word dissolving into its waters, the word ‘globe’ is also thought to refer to Shakespeare’s own favoured Bankside theatre, The Globe.

You do look, my son, in a moved sort,

As if you were dismayed. Be cheerful, sir.

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air;

And like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve,

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep. Sir, I am vexed.

Bear with my weakness.

Prospero knows that this is a charged moment, for Prospero is in process of first disinheriting Ferdinand, as son of a father who had deposed and cast off Prospero to death on the sea with his infant daughter, whilst reestablishing Ferdinand’s fortune in cementing the link to his daughter, Miranda, who will inherit that throne Ferdinand might have thought to be already his. it appears everyone has to large about the ‘large question’ of the world – of the instability of power at one level for dukes and kings but also the instability of life when preyed on by human mortality and ‘weakness’. So let’s ‘dissolve that hard world’ and its hard words – like pain, betrayal,banishment, murder, and death – and think of the world as nothing but sleep haunted by dreams, except that to dream we must sleep and, in sleep, chance can take over for those still awake in the world – as it does to many on Prospero’s island – and in the end, sleep is a metaphor for a longer, harder kid of unwaking sleep – that of death unto the decay of the body.

Why would I choose ‘dissolve’ as ‘favourite word’ then in the light of its own dissolution into a specialist word, most useful when describing a method of creating a solution of two compounds – one a liquid, the other a solid or semi-solid – in a natural science experiment of some kind with no suggestive aura around it, such as it had for Shakespeare and Keats. That is, after all, not my style – definitively thus being a lover and defender of what used to be called ‘purple prose’, a love I used to favour in a blog the wonderful novel set on a slave plantation by Robert Jones Jr, The Prophets, with its theme of defending softness in relationships from the claims of rigid and hard themes in human life reduced to basic where soft flesh is the easier to eradicate (see my blog at this link). I chose it because of encountering its use by Colm Tóibín in a beautiful prefatory essay, called Night, in reference to its primary subject matter Pat Steir’s 2021 – 22 painting of that name, to a recent book on Steir’s art from 2018 – 2025.

This essay largely constitutes an almost perfect description of Night that derives from a kind of refusal to ask of it the questions usually asked by art historians:

I wonder if it is possible to see this painting as a thing alone. … I wonder if this painting demands that we forget art history, we forget what it meant for an American woman born in 1938 to become a paqinter, what she had to learn, what strategies she had to use, what she had to shed. The painting asks all these matters to dissolve. (1)

In defying the hard traditions and rigid repertoire of art historical questions, Tóibín calls for them to ‘dissolve’, such that what matters is whatever we decide to be ‘the painting’ itself and goes about devising questions that might reveal the ontology of that painting as precisely as possible without reliance on art history, including the biography of the artist qua artist in her historical context. Questions follow thus: ‘How is the painting’ …made, structured, described in the terms of how it is made and structured? But such a choice brings with it its own problems. who decides that this painting is appropriately entitled Night and why? As we are told, Steir did not set out to paint ‘Night’ as such. In fact she ‘worked on the canvas and then needed a title’.And since many other paintings in this volume are titled Untitled, I wonder how accidental that title Night is, a matter of chance depending on how the painting went in process. And ‘chance’ we are told by Tóibín and by Steir in a conversation later in the book with Evelyn C. Hankins is a function of both the making and structuring, in part (for Steir insists she only shows art that has at some point been under her control in some way): ‘ The paintings that are too out of control; you never see. I learned about chance from John Cage and Merce Cunningham. …’. I have linked the names she cites to allow it to be clear that both artists credited for teaching Steirs are performance artists (in musical composition and dance respectively).

Performance cannot be fully intentional in its control – it is performance by virtue of chance having agency in the art itself, which Steir relates to things the paint does, apparently of its own agency though she controls its qualities as paint when it is thrown or spilled on the painting but never ‘dripped’ as Jackson Pollock did: ‘Dripping is not macho enough from me’, she states in a rather nice side-sweep to Jackson Pollock’s anxieties about masculinity, although she does not identify it as such. (2) The issue is that it is more than the questions asked by art historians that get sidelined and ‘dissolved’. And from now my love of Tóibín’s brilliant use of the word becomes itself uncontrollable. here is another instance – the first that grabbed me. (3)

For the action of painting, including the actions taken by the paint once dropped, spilled or thrown on the canvas (not ‘dripped) make and revise the structure of the painting from that of its architecture of lines – sometimes a grid in some paintings. For though Steir does not drip paint, the paint once applied acts as it must based on its density and volume as it dries overnight and it drips, such that Steir’s painting relies on the differential dripping of paint by natural energy contained in its disposition as it flows in drips from where and in what quantity and by what force it was thrown or dropped. The things that this process of restructuring implies is the dissolution of the idea that might have intended it to be disposed where it is in the first place. Did Steir want ‘large questions’ to be asked by her painting – about the nature of light and darkness, day and night, matter and spirit’ and their scale of conflict and compositional fragmentation when brought into play with each other or are these ‘ideas’ and ‘large questions’ secondary to their dissolution into the action of painter and paint together: ‘an idea that has been rendered into action enough for the idea itself to dissolve or be best dealt with as a simple description of what has happened’.

The irony is that in dissolving the idea, a solid isn’t turned into liquid solution by the idea has been turned through its illustration by performative action (the ACT of painting) eventually itself into a ‘solid’, a ‘thereness’ not something soft and airy like the visions conjured by Prospero or the soft fading sounds and colours of a bird singing invisibly in the distance. In my view, this little essay alone makes the word ‘dissolve’ live again and brilliantly. However, in doing so Colm Tóibín restores the word to its context as the art of poiesis, the art of the making of art or even meta-art. no wonder Tóibín’s essay goes on to query the reason for the title of Steir’s artwork by brilliant analysis of poetry by English Renaissance poet Fulke Greville, T.S. Eliot and then Rainer Maria Rilke. In truth, this is critical brilliance on art across all genres, and all because Tóibín understands the word ‘dissolve.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

_______________________________________________________

(1) Colm Tóibín (2025: 11) ‘Night’ in Jake Brodsky, Sussanah Faber et. al. (Eds.) Pat Steir: Paintings 2018 – 2025 Zurich, Hauser & Wirth Publishers. 11 – 16.

(2) Pat Steir with Evelyn C. Hankins (2025: 201) ‘In Conversation’ in Jake Brodsky, Sussanah Faber et. al. (Eds.) Pat Steir: Paintings 2018 – 2025 Zurich, Hauser & Wirth Publishers. 201 – 204.

(3) Colm Tóibín op. cit: 14

One thought on “The word ‘Dissolve’ might aid those who find the things of the world they inhabit too resistant and too ‘solid’, but it is a word that in this helpful usage seems itself to be fading away.”