‘ … when what’s healthy and joyful is hidden, you never learn to tell the good and bad apart’.[1]Institutions, and the Irish Roman Catholic Church is one such, often control what we are allowed to see or witness and what we are allowed to remember or record of our witness of events (what we have seen or heard). Is that why if we are ever to mature our sense of the meaning of queer relationships in history and the present, we may need to turn to why the Irish Church exerts such control over the making of a moral discrimination and ethical judgements of Irish selves and how queer people in Ireland were influenced by that model of seeing, thinking and remembering.

Niamh Ní Mhaoilcoin (2025) ‘Ordinary Saints’

I was not expecting to read and enjoy reading a novel that is by a queer writer and about queer people, across a wide range of definition, but focuses on precise knowledge of the means by which a ‘cause’, a claim for the canonisation of a dead priest as a ‘saint’ occurs and why it occurs that way.

But I know why such an apparent division of subject matter works now having read this novel. It is because this novel is, more than any other I have read, at heart a novel about how queer people see each other within networks of complex and intersecting chosen and biologically determined familial or close relationships. It shows how desire for connection of all kinds mould them as present beings and as remembered ones. The process of canonisation is precisely that; a process of sifting the meaning of events, words heard, and scenes seen from the candidate’s life. And all of us do that to each other before and after the feath of any one of us.

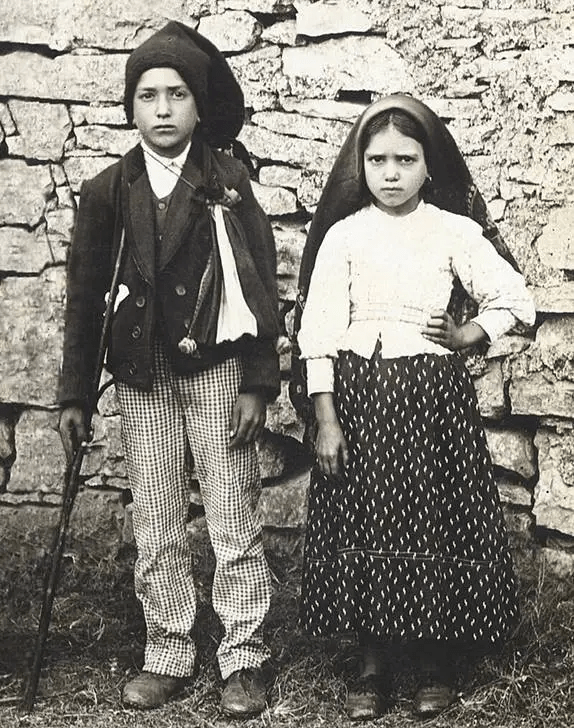

However, that similitude of canonisation to everyday and ording co-evaluation of humans of each other is not clear to the novel’s lesbian narrator, Jacinta, at the beginning of this novel. To her canonisation is a process beyond anything we could call ‘ordinary’. The name Jacinta, by the way (as the novel makes clear), is the name of a saint canonised together with her brother whose story gets told in the novel. This is why the girl named Jacinta at birth, by her devout Catholic mother, prefers therefore to be called Jay.[2]

Francisco de Jesus Marto (11 June 1908 – 4 April 1919) and Jacinta de Jesus Marto (5 March 1910[1] – 20 February 1920)

Jay discovers that the colleague priest and dearest friend of Ferdia, once nearly (if that is possible) as beloved ‘as a son’ as Ferdia by the whole family, has now left the church, admitted to being in love with Ferdia when Ferdia was alive, and since leaving the church, renounced Catholicism and is living, without the celibacy he enjoined on Jay when she came out to him whilst he was a priest, with his male sexual partner. As Ferdia is pushed towards and through the process of the ‘cause’ that will test his sainthood, and Jay pushed too by the strong currents of ’cause’ making, after Ferdia’s early death, certain facts about Jay’s own wishes in regard to her brother become clearer to her.

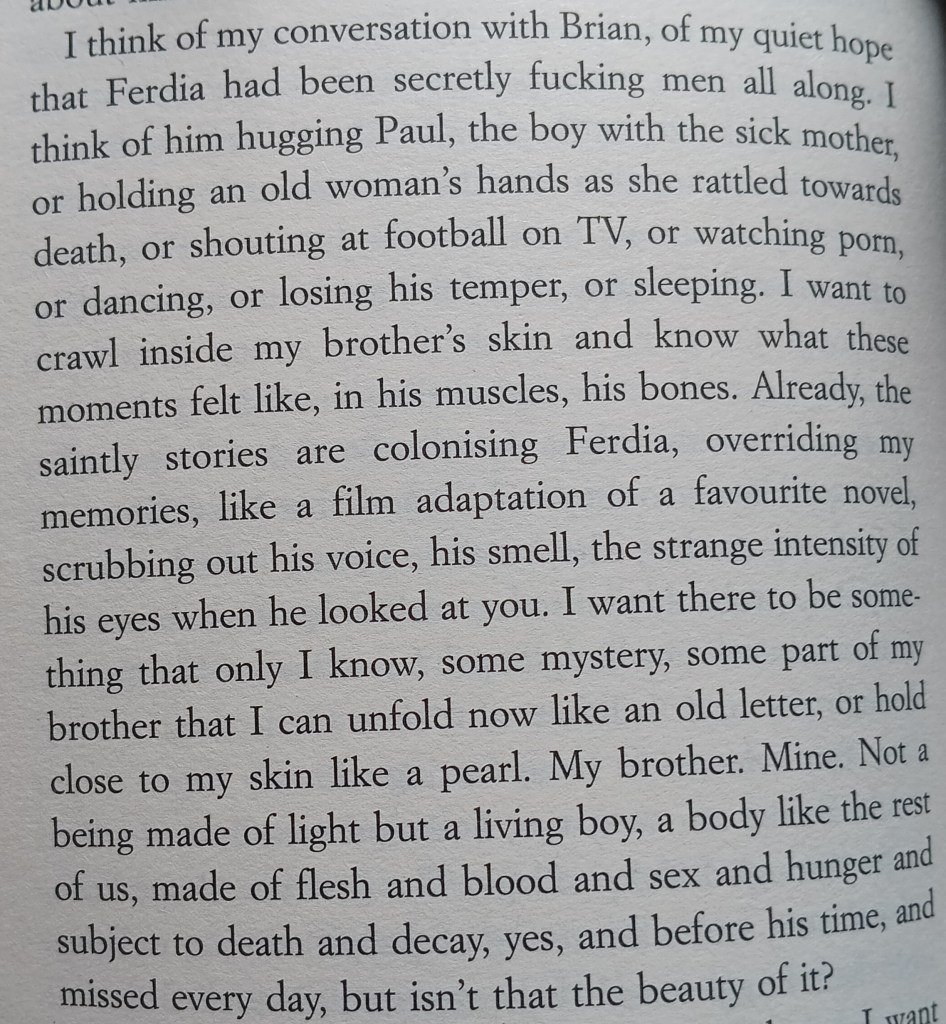

Jay realises that that she has latterly lived ‘in quiet hope that Ferdia had been secretly fucking men’.[3] Queer people, after all, like every other person desire to see those they love in some kind of understandable relationship to how they see or wish to see themselves. The novel then poses a dilemma, hard to see in any other circumstance than canonisation, that this process of absorption of the beloved other into the future hopes of yourself, even to the point of the reinterpretation of their past behaviour, words or other ‘evidence’ for your hope that he was ‘secretly fucking men’ isn’t totally unlike what the Church does in attempting to absorb Ferdia as a saint amongst its own authorised canon of saints. Canonisation, as I have said before, involves the Church in a complicated process of testing the validity of the saint’s action and ‘miracles’ before and after death, and in searching through everything that remains to witness him – whether living persons, records in written or other form taken by the candidate for canonisation, even when these records were innocent of seeking that end, or taken from others that witnessed something in the appearance, actions, words or behaviours that might have a relevance to potential sainthood.

Those processes are not unlike those any one person, or category of persons like the category of Church members or queer communities, uses to evaluate the worth of one individual related to them, after their death or even before it. Though queer communities ‘may’ not look to an afterlife in asserting the queerness of our lost beloved, we certainly equally search the past and examine what hope for others might spring from the relics of their contribution to the cause of validating at least one diverse type of a queer life.

Faced with her own memories of the trials of ‘coming out’ in Ireland and challenging homophobia, Jay despises the eulogy by Father Mannion on her brother based on his cause for canonisation. His speech recalls those memories whilst using her brother as an antagonistic witness to homosexual marriage or love. Mannion’s eulogy instanced how, when three unruly boys ‘sat in the back corner of the classroom, smirking and exchanging notes’ being taught by Mannion, with Ferdia present as a newly ordained priest-observer, the trio started asking questions about, amongst other things problematic in Catholic belief about contemporary morality, ‘the parameters of normal healthy sexual life’.

Mannion sees ‘cause’ for saintly status in Ferdia disagreeing with Mannion’s anger about this classroom episode and mitigating it by pointing to the need mainly to pray ‘for these young people, who were growing up in a time of such change and confusion’. Nevertheless Mannion continues by saying the present celebrants should not believe that ‘Ferdia wasn’t as troubled as I was by what these young men had to say’, and affirming that, from this subjective evidence, Ferdia when alive opposed marriage between two men. [4] Publicly, at the celebration following this service, she declares Mannion and his Church to be ‘actually still really homophobic’, only to raise laughter amongst her extended family and community, forcing her to say what Mannion said insulted her whole life. At this point she hears a close male relative say: “You’re not telling us you’re like that, are you, Jacinta?”[5]

And though she never fights that corner of the argument, it is clear that she does not accept that Ferdia either would be like Father Mannion says he is, and that his defence of the three boys went deeper into recasting future relations between Church belief and a degree of openness to diversity and the life potentials diverse secualities might offer the Church. In fact Ferdia’s ‘cause’ (the official name for the canonisation process) actually only intensifies Jay’s feelings about Ferdia’s religious career. She always hated, and hates more now the fact that the Church assumes it can ‘know’ Ferdia and know him better than anyone else, even her, once their process has run its course, including the writing by Father Richter of a definitive case based on the evidences of his life and death, his ‘positio’.

That Jay thinks that is in honour to the fact that principles of diversity not only mean that people differ from each other, even within categories of communal description of themselves they accept (like being a college of priest or a ‘queer’ community), but that they can change in diverse ways through time. When Jay argues to Father Richter that she has found ‘so much more virtue, more hope and charity and justice in the queer community than I ever did in your institution’, he answers that she needs to recognize that her ‘brother built his life in our institution’ (the italics being the authors and marking an emphasis made by Richter).[6]

There is no doubt that Jay needs to learn more not only of the meaning of the Catholicism in which her family has lived, even from a secure position now outside it, but also about ‘the queer community’ too. Though she may praise the latter, she does not learn successfully to accept its own inner diversities and to change to adopt a relationship with them until the novel’s ending. Jay’s relationships with her own ‘queer community’ grow better through this novel. About some aspects of that community that she thought she knew already, she begins to learn for the first time in the novel – with regard, for instance to her friend Clem or her lover Lindsey – just as she must with some Catholics, like Brian, the queer ex-priest and her father and mother.

Knock

Nevertheless the Church makes some extreme claims in the possession of those it wishes to canonise, even down to making a claim to not only interpret but also own every piece of evidence of the person, even down to his body. Things he once co-owned with his family that have became his ‘relics’ can henceforth only proclaim one meaning – a ‘witness’ to the holiness of which they once were only a partial representation. This is dealt with in very moving scenes (there is more than one) at Ferdia’s grave. In one Jay learns about her parents gifting the body of Ferdia to the Church, in the event of moving forward in the ‘cause’ in order to ‘protect the holy remains’, even to the point of, once they are exhumed, not being buried again. This is not only a transfer of ownership but a possession of everything that once was Ferdia separate from his clerical career, in Jay’s memory and perception, and their interaction to a tomb in Knock, surrounded by other relics of Irish holiness. [7]

It is at the moment that Ferdia tecognises that she had always hoped that Ferdia, Luke her before coming out, had been secretly queer. She fears too that the canonisation of Ferdia will mean both she and Ferdia lose the significance of their relationship as brother and sister with relics of their relationship in their own possession and free to reinterpretation. With that she fears as well the loss of that potential, in the event that he had survived the head injuries that killed him, that in continuing to live his life, he might have changed as all others do to something less regulated by church or supernatual forms.

There is more ‘inside’ Ferdia, even dead, she believes than the Church can exhume – things she, or others knew that change not only memories of him but what he is to them and what he could be in the future – even as an evolving memory. No one ‘institution’ (not even the queer community) can own and interpret everything that is a relic (abstract or physical) of a past moment.

The passage below points to all of the memories that don’t get owned by the church but are shared with us in the novel.[8] The beautiful passage records our resistance to the ‘colonising’ of a person, even their memory, by a hegemonic institutional reading of them – one bound in personal ‘relics’ like ‘an old letter’ or a ‘pearl’ – and because we own them what we do with them, such as ‘hold them close to my skin’.

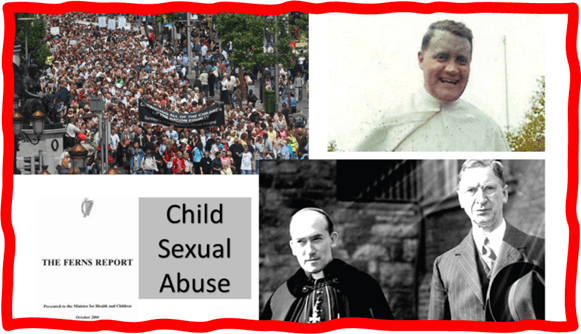

One of those memories mentioned above I will analyse a bit further for it touches on a Catholic priest about whom the most extreme memories in Ireland have been called forth, even in Irish novels by Sebastian Barry and John Banville, and essays by Colm Tóibín (see the links if you want to see my blogs on two of these). The all relate to how evolving history had the effect of complicating the legacy of Archbishop John Charles McQuaid, who many once would have looked to be a candidate for canonisation. The photograph below shows some of the events referred to in all the Irish writings above:

Child Abuse Reparations Protest in Dublin from The Times at https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/millions-still-outstanding-in-child-abuse-reparations-zvh3976zt?region=global; Kilbarry1 (13 Feb. 2020) John Charles McQuaid and Eamon de Valera, December 1940 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:McQuaid_de_Valera.jpg; Illumina29 Father Brendan Smyth. This version was cleaned up from stains by uploader. – Illumina29’s own photograph, a bit damaged from a recent flood. He took this photo when he was about 9 years old, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=125044

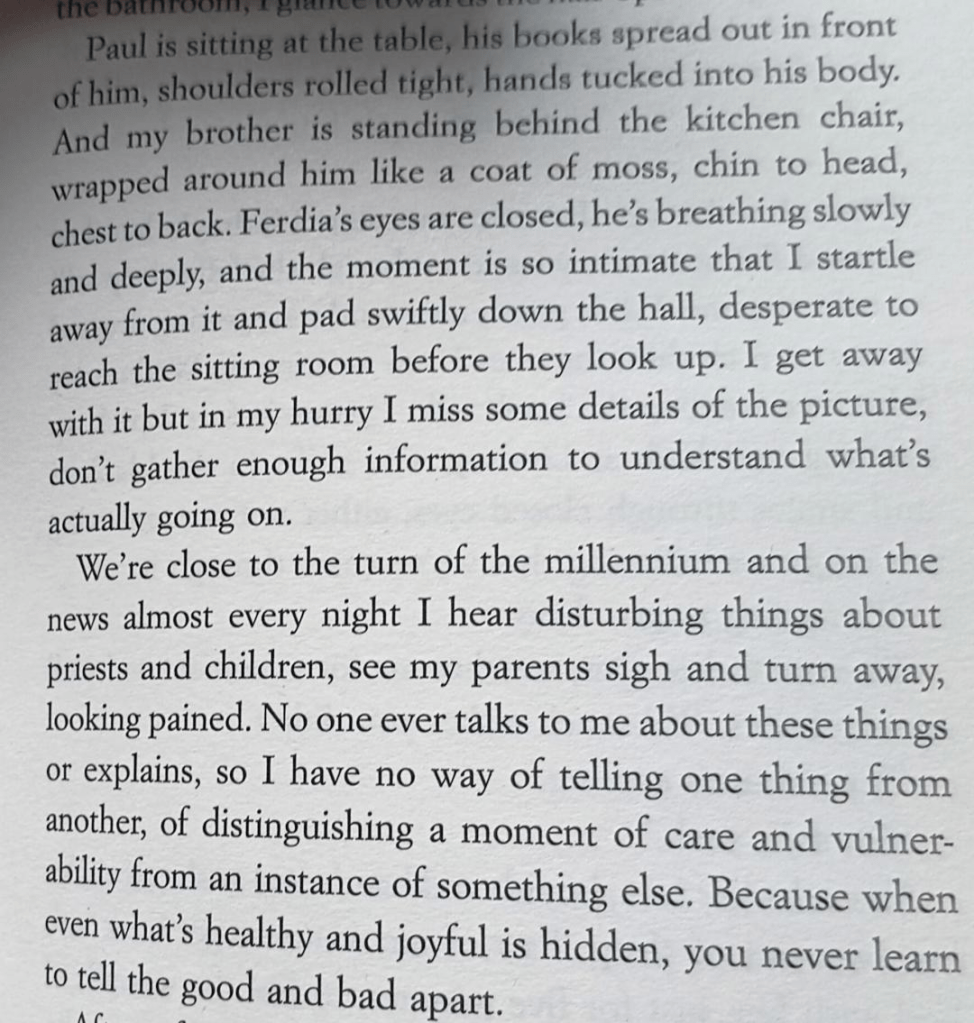

We hear of these events associated with McQuaid indirectly in the memory Jay has of her brother ‘hugging Paul, the boy with the sick mother’. Jay recalls earlier that Ferdia, just after taking his Leaving Cert as a priest, has to run an errand on the way home from collecting her from school to visit a woman dying of bowel cancer. Whilst Ferdia goes to talk to the dying mother, the woman’s son, Paul, sits alone in the kitchen doing his school homework, whilst Jacinta sits in another room waiting and reading a book about heroin addicts. But Ferdia comes back downstairs from the dying mother to comfort the boy acting as her carer downstairs as the teenage Jacinta is using the toilet. Coming quietly out of the toilet, she glimpses this scene through the ‘half-open kitchen door’:[9]

There may not be the extensive concern about unearthing the truth about the scandals that circled the career of McQuaid, but there is enough to place it at his feet, as it became clear that McQuaid cleverly concealed and covered up the truth of child abuse stories in independent Ireland. But the point here is not that what Jacinta sees, and what Jay remembers, provides witness to fixing Ferdia up as a perpetrator of child abuse. To Jay, it fits in a repertoire of memories of how close Ferdia might be to males, how naturally his body covers other male bodies ‘like a coat of moss’. The scene is neither sexual nor abusive, but it has difficult-to-interpret details – like Ferdia’s ‘closed eyes’. Is this an attachment that is akin to romance and sex but is neither? Since we know so little about how men relate as ‘caring for each other when vulnerable’, do we interpret it with the majority as ‘an instance of something else’, something abusive. Hence her comment, quoted in my title: ‘… when what’s healthy and joyful is hidden, you never learn to tell the good and bad apart’.

And for this the Church is also responsible. Just as it tries to own and interpret everything about its saints, so does it with its functionaries and people of power in their hierarchies. And Jay is more than once ready to bring up the pernicious name of McQuaid. She finds that the airport chapel through which she passes is named after him, a thing that an elderly Capuchin monk, that she finds in there, raises his eyebrows over.[10]

But is there more to the Irish Church than corruption and homophobia? I think the novel wants us to leave an opener here to allow us to understand those who at some point seek its embrace, like Jay’s mother, who also actually learns to change within it. Jay rather than continually thinking that her mother is to blamed for the neglect of her as a child at the time of acute mental illness for not seeing ‘me grow up’, suddenly finds she must learn to see that her mother needs space to ‘grow up’ too and to be watched over with care doing so. The learning brings her closer to her own partner.[11]

And maybe there are subjective truths in the fact that we honour something special in the dead by evidence, perhaps for some of us only in metaphor, like the smell of incorruptibility or for an aura of light around them, as Brian does Ferdia, despite Brian’s lapsed state as a Catholic. Maybe queer communities learn from these mind-states too, if not by a form of them that looks equally ‘institutionally’ enforced (by Pride dogmas for instance).

The novel, after all, insists that we ALL think too simply about the potential for change in ourselves and others, not just the Catholic Church. Our memories change us as much as present events do. We can all become many things at once – but often, only one aspect of our being is honoured. Moreover, though it certainly is the case that, in Rome, Ferdia sounds too much like a ‘smug priest’ it does not mean he can’t also struggle with being a queer priest, a caring priest, a loving man, if Jay will allow other people’s memories of him to matter as much as hers. After all, that is what she blames Father Mannion for. The moment in Rome, just after Ferdia talks clerical gossip about the candidates for the next Pope, is too lovely not to quote:

He lifts his eyebrows knowingly, but then quickly takes such an enormous bite of his bun that his cheeks get dusted in icing sugar.

“Stay classy, Ferdy,” I say, and he looks at me. I laugh and so does he, then we get giddy and laugh harder, until he’s struggling even to chew. The smug priest is finally gone, we’re giggling like children. …[12]

It’s beautifully done that transition in which the two people co-author each other’s memories of each other that will be from even earlier memories – childhood ones. However by the end of the novel, the most profound of its lessons is that in a simple exchange – about change in parents, their children, your acquaintances and friends and each other, if you are lovers, and that this combined cooperative changes includes those of our subjective judgements of each other, also changing in time.[13]

And the beauty of the novel is that Jay only learns about how to really value queer community by going beneath the dogmas of queerness as a category – seeing diversity across the range of characters like Clem, even that his struggles with a Protestant upbringing were as problematic as hers with the Catholic Church, or seeing that queer love can take queerer forms like the way Brian, now no longer a priest and no longer Catholic in faith, eventually loves Ferdia by including in that love Ferdia’s aspiration to ‘goodness’ in a Catholic model. I loved this novel.

However, perhaps it is only in the Irish context that queer novels about the problems of moral perception and historical memory and its record can be initiated, for there the institution of the Roman Catholic Church with its insistence on the need for controlling the meaning of relationships and their recording in history is an unchanging fact of Irish histories and biographies, written or otherwise. And thence this novel succeeds in a domain that I had not expected to be covered in the queer canon. But there ya go! Ain’t diversity wonderful

Do read this lovely book!

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Niamh Ní Mhaoilcoin (2025: 159) Ordinary Saints London, Manilla Press

[2] Francisco de Jesus Marto (11 June 1908 – 4 April 1919) and Jacinta de Jesus Marto (5 March 1910[1] – 20 February 1920) were siblings from a hamlet near Fátima, Portugal, who, with their cousin Lúcia dos Santos (1907–2005), reportedly witnessed three apparitions of the Angel of Peace in 1916, and apparitions of the Blessed Virgin Mary at Cova da Iria in 1917. The title Our Lady of Fátima was given to the Virgin Mary, and the Sanctuary of Fátima became a major centre of global Catholic pilgrimage. [Francisco and Jacinta Marto – Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francisco_and_Jacinta_Marto ]

[3] Niamh Ní Mhaoilcoin op.cit.: 280

[4] Ibid: 223 – 225.

[5] ibid: 236 – 238

[6] Ibid: 69f.

[7] Ibid: 205 – 208

[8] Ibid: 280

[9] Ibid: 159

[10] Ibid: 174f.

[11] Ibid: 334f.

[12] Ibid: 327f.

[13] See ibid: 345f.