What foods would you like to make?

To sustain the body, we need to feed it, and in order to sustain it optimally, we need to select and pace the amount, degree, and type of food we use to feed it. So far everyone will agree!

However, the excerpt from the Alice books of Lewis Carroll above shows that the food we take is mediated by two factors independent of reasoning about where, when, and what to eat or drink. First, we feel that our choice of feeding or drinking input should be involved – we want someone to ask whether we would like this or that intake available – and, second, the food you are offered to choose ought to be actually available.

The point is that dining with the Mad Hatter and the March Hare is not going to feed you optimally but only on the basis of an already prescribed menu chosen by others: in this case a menu of one item, ‘TEA’.

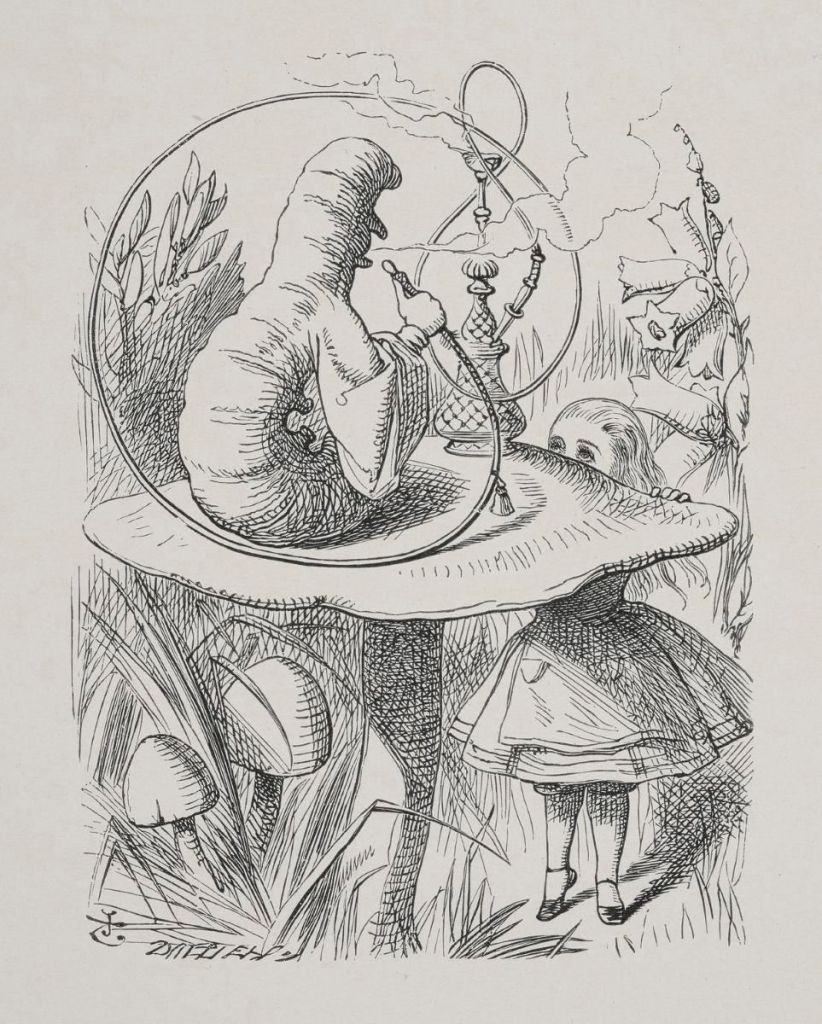

Carroll seems constantly to wonder why we accept eating or drinking anything we are told to eat or drink. Alice finds ingestable things constantly and only needs to be told to ingest them, like a magic mushroom by a caterpillar sitting on it smoking a hookah of opiates:

or, from a bottle with a label saying ‘Drink Me’, in order to do so and then bear the consequences on and in her body.

The unspoken lesson is that we can not always take into the body everything suggested to us, like the wine suggested by the March Hare if it is not available, nor should we always consume things others want us to consume.

Carroll took this so seriously, he used the metaphor of feeding to talk about not only the care of the growing, or reducing – perhaps to ‘nothing’ fears Alice as she shrinks, body but also to the growing or shrinking mind. A lesser known work of his is Feeding the Mind. Here is a sample from the short piece.

First, then, we should set ourselves to provide for our mind its proper kind of food. We very soon learn what will, and what will not, agree with the body, and find little difficulty in refusing a piece of the tempting pudding or pie which is associated in our memory with that terrible attack of indigestion, and whose very name irresistibly recalls rhubarb and magnesia; but it takes a great many lessons to convince us how indigestible some of our favourite lines of reading are, and again and again we make a meal of the unwholesome novel, sure to be followed by its usual train of low spirits, unwillingness to work, weariness of existence—in fact, by mental nightmare.

It is typical of Carroll, professing mathematics and symbolic language as a university teacher known as Charles Lutwidge Dodgson in Oxford, to think that the most healing mental food is the most logical input. In Feeding the Mind, people who.ignore logic and are indiscriminate over-eaters and drinkers, he decided to call ‘fat minds’.

I wonder if there is such a thing in nature as a FAT MIND? I really think I have met with one or two: minds which could not keep up with the slowest trot in conversation; could not jump over a logical fence, to save their lives; always got stuck fast in a narrow argument; and, in short, were fit for nothing but to waddle helplessly through the world.

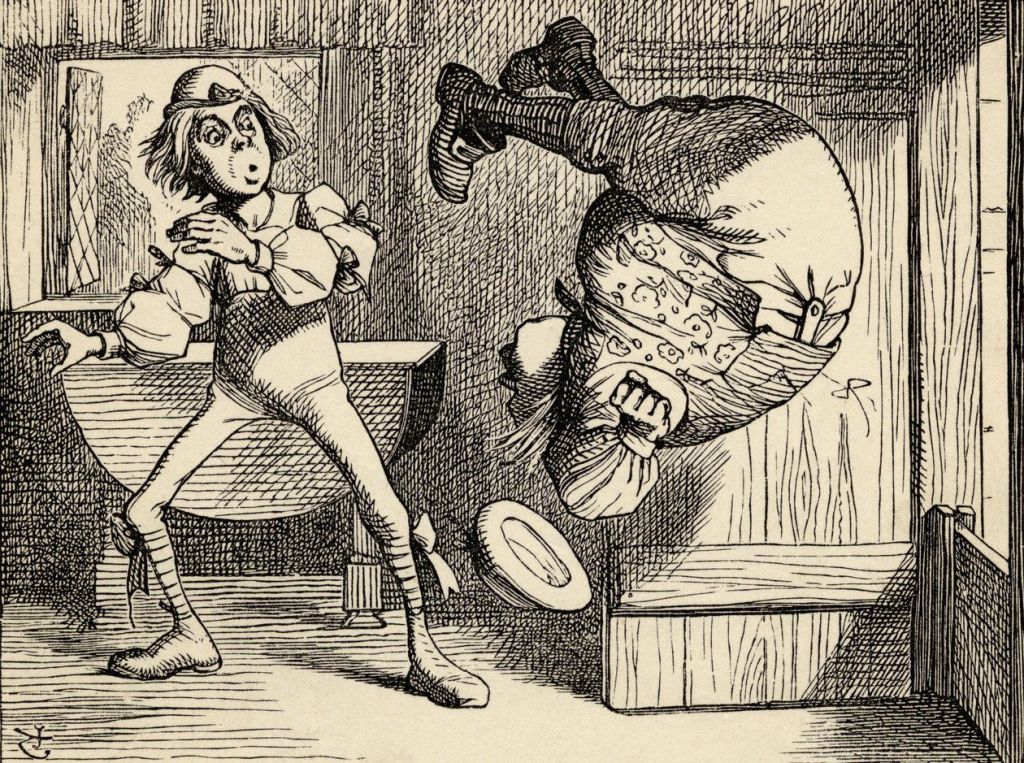

But there is a limit to logic that even the very sparse body and logical mind could not fat-shame as above when he turned to fantasies that validate human individuality and emotion. Think of Father William, whose son continually questions him about the rationality of his everyday behaviour. He pulls the rug from under the son when the latter sets out to, amongst other things, fat-shame him:

You are old," said the youth, "as I mentioned before,

And have grown most uncommonly fat;

Yet you turned a back-somersault in at the door —

Pray, what is the reason of that?"

The thing I take from Carroll’s Feeding the Mind is that we take too little care of feeding those parts of the inner being that generate, process, and work with the need for consulting the emotional impact of our being, and of a world often ready to ignore emotional.responses to its own processes that it justifies as necessarily neglectful of suffering.

It seems no longer possible to invoke even the suffering of huge masses of Palestinians, murdered while collecting food to feed their families or derived from the use of food shortage to fight ‘wars’.

The whole world feels it okay to accept that people die in conflicts who were not otherwise than passively involved in them and are merely trying to survive. It is mature to accept collateral suffering (we are often told): that is the world we live in, and we must be realists!

What feeds that moral desire to not accept the world as it is, but as it could be changed to be? It must involve respect for imagination that refuses to accept that only things that have persisted over time, regardless of the fact that only the interests of the powerful few are served by them, are what is the ‘real world’. I wish I could MAKE THAT FOOD.

All for now

Love Steven xxxxxxx