Last night, Geoff and I steeled ourselves to watch the final sessions of Midnight Mass on Netflix, another blockbuster event. I say ‘steeled’ ourselves but that was not because of , up to the final episodes, of any terror at the violence and gore in it, but it’s totally serious attempt to listen to conversations between persons on matters of significance. And that can get trying, especially when you are expecting a half-baked version of the Christian message, toned to the American Evangelical of all denominations. Let’s face it, Midnight Mass covers all the stops such messages require: the meaning of addiction to material substances, the values necessary to parenting, the duty of individuals to the community, and even of the relationship of particles to a physical mass. The latter, too, is near the knuckle of this series’ interest in the nature of social and ritual communion: the deeper meaning of Catholic Church Mass.

Mass now to offered to masses. At the beginning of the film, we are shown that only two people regularly attend Mass until the miracle of revived life becomes to be associated with it.

And, of course, there is a binding conversation about the nature of life in time and out of it – in continuities that even want to stretch to eternity and other infinities. The final discourse on after-life in the series by Erin Greene (Kate Siegel) considers how masses of particles that make up human being disperse into the cosmos and is a repetition of the long speech by Riley Flynn (Zach Gilford), the alcoholic whose drinking in a fast living New York has led to the death of a young girl following his driving asleep in alcoholic stupor at the wheel, when asked about what death meant to him.

To him it meant satisfying dissolution into something more whole but without consciousness, whilst to Erin Greene at the very end it means the disintegration of our need to build in a ‘self’ as something different from the whole. The only self that survives for her [for Riley it is the ‘Cos- mos’] ,is the mass of undifferentiated being which can say with Yahweh, ‘I am that I am’, precisely because what I and we are are undifferentiated, even from the atoms of tbe cosmos. It is not unlike Samuel Taylor Coleridge‘s definition of the human imagination as an instance of the being of God:

The primary Imagination I hold to be the living Power and prime Agent of all human Perception, and as a repetition in the finite mind of the eternal act of creation in the infinite I Am.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ‘Biographia Literaria: Biographical Sketches of My Literary Life & Opinions‘

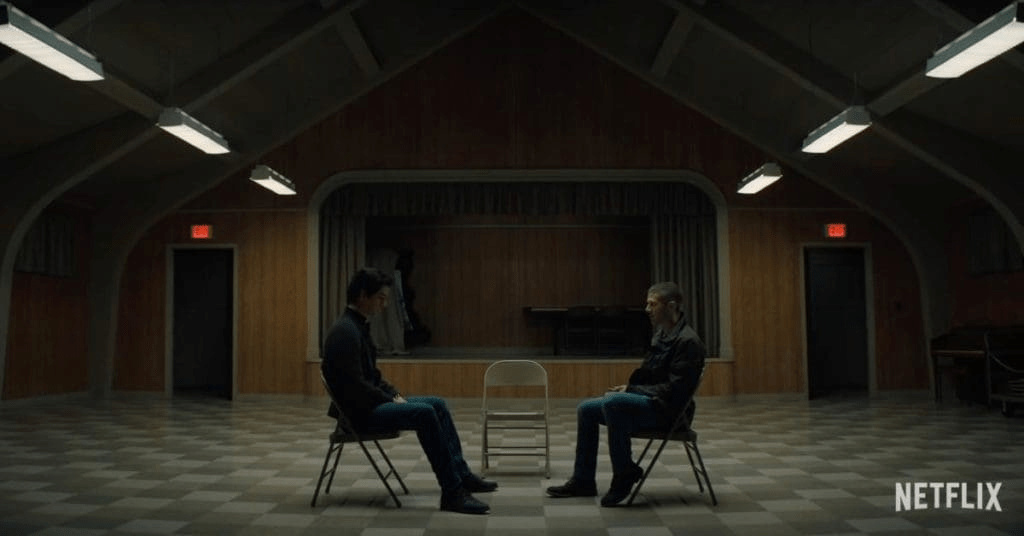

But others confront death and loss too without the trapping of social ritual or with a thinner version of it than that celebrated in the Mass, or Holy Communion, for communion is a sharing of common loss in the community its, significantly in the very material that has been lost, the body snd blood of Christ. The mourning and recovery loss of self and its dignity that accompanies alcoholism has very thin trappings, and this is symbolized in the meeting together of addicts seeking purpose from a Higher Being that is an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. Here is the first meeting in which the town alcoholic, Joe Colley (Robert Longstreet), is not present except by virtue of his empty chair.

Two individuals face to face, and a missing third, in addiction and in search of a Higher Power

Joe Colley in the film is a reminder to Riley of the man he could become – a person cast-off by the community and unable to share any kind of communion with it. His major loss in the film is of the one being he can love – his dog, whose death leaves everyone indifferent but him.

Joe Colley mourns his dog alone amid indifference and no hint of ritual absorption of the loss on offer

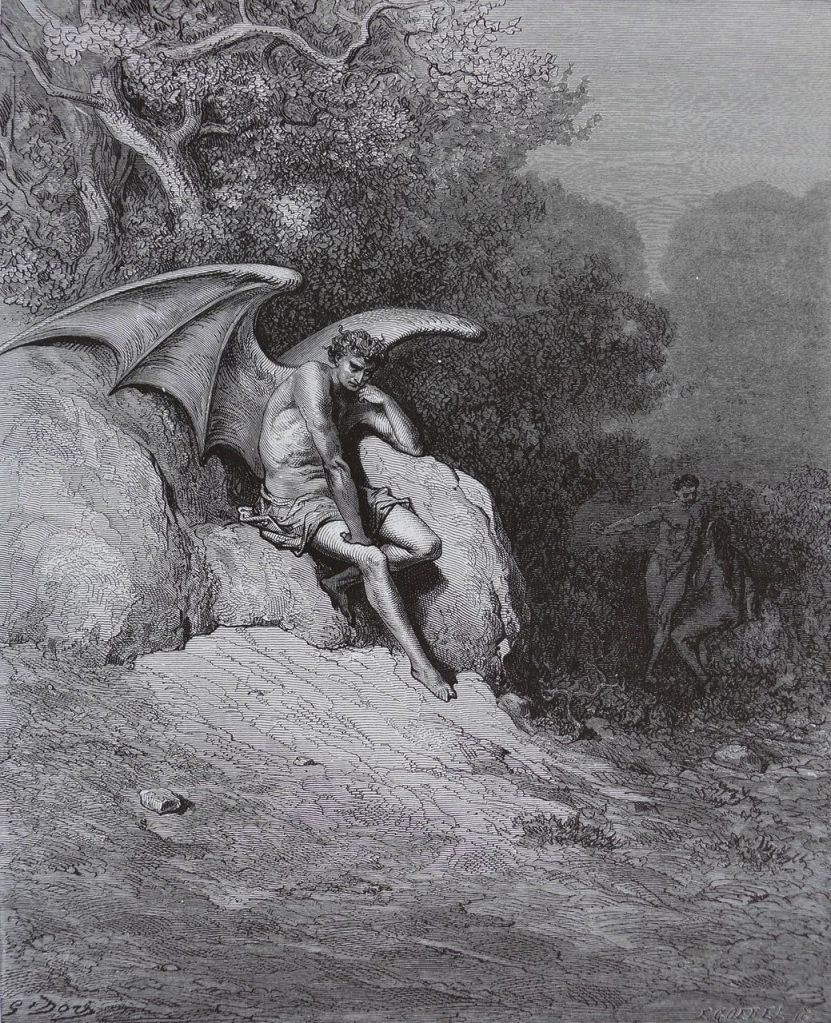

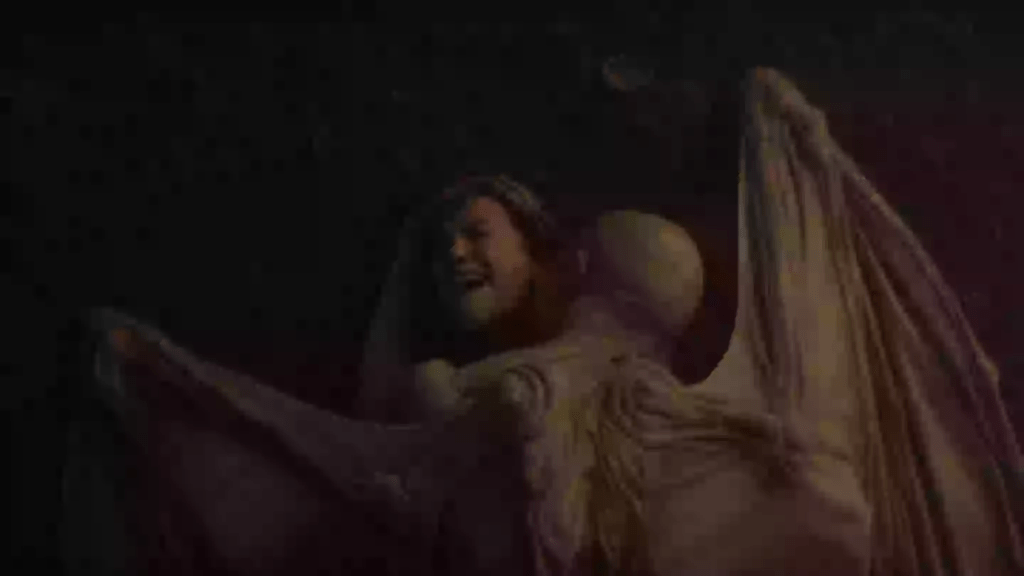

But the memes of the show on full display in the more telling poster below are those of a confluence of religious myth [after all the titles of the show episodes start with Genesis, begin to find the story starting to find ritualistic (if inverted) coherence in Gospel and the Acts of the Apostles, ending luke the Bible too with Revelations, the book of the Apocalypse in which reference is made to both the Antichrist and the Scarlet Woman, The Whore of Babylon. Yet already the Angel on the poster reminds one of Gustave Doré‘s depiction of Satan in his illustrations to Paradise Lost, with the same bat-like un-feathered leathery wings

Doré’s Satan as fallen angel with bat-like un-feathered leathery wings

Another poster with narrative spoilers and more of the religious memes and a stress on the disadvantages of leather in wings.

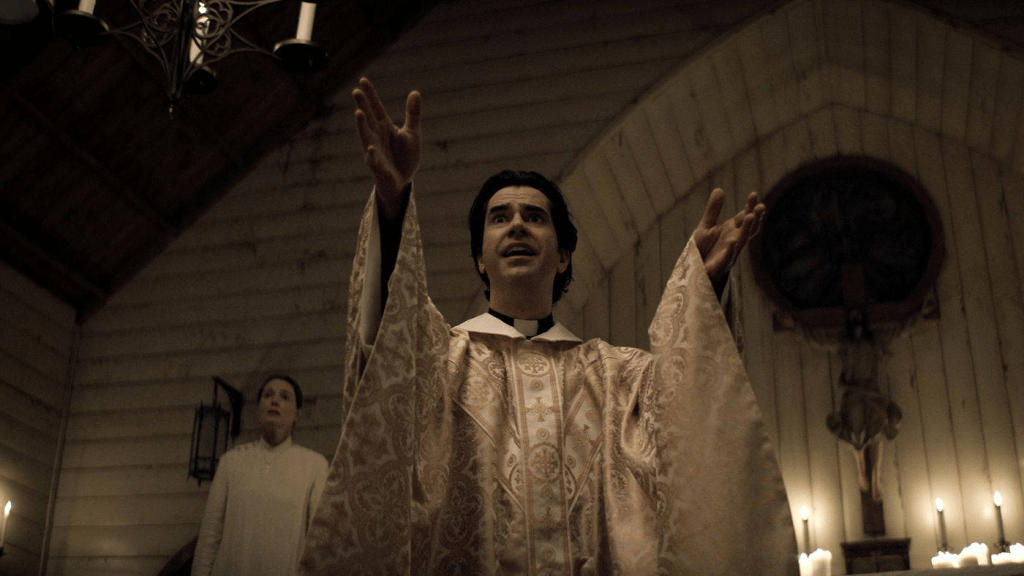

Over-ridingly, the chief discourse of eternal life is the doctrine of the resurrection, although massively turning to that end-ofdays myth of the eternal life in the body. This myth becomes yoked to one the return of the body to its best days, prior to the onset of disease, accidental disability or even ageing. No corpse, however, is revived for the process is linked to the ingestion of the infected blood of the vampire. Central to the regeneration of the body is the experience oc the priest of the island village community, totally population in the low 100s, is Father Paul Pruitt – a man in his eighties (in youth played by the seductively charismatic Hamish Linklater), reported as in tne early stages of dementia that and incapable anymore of fulfilling his role.

Father Paul is sent on retreat [some retreat we might say] on pilgrimage to Jerusalem but wanders off into the desert and like a other Paul (then Saul the Jewish religious official) hits the ‘Road to Damascus’, where he is converted in tje dark of a Byzantine Chapel unburied by a sandstorm by an Angel.

Father Paul at the entry of tbe uncovered Byzantine Chapel before entering the Dark.

The ‘Angel’ (Quinton Boisclair) is discovered in the Dark by Father Paul on the strike of a match.

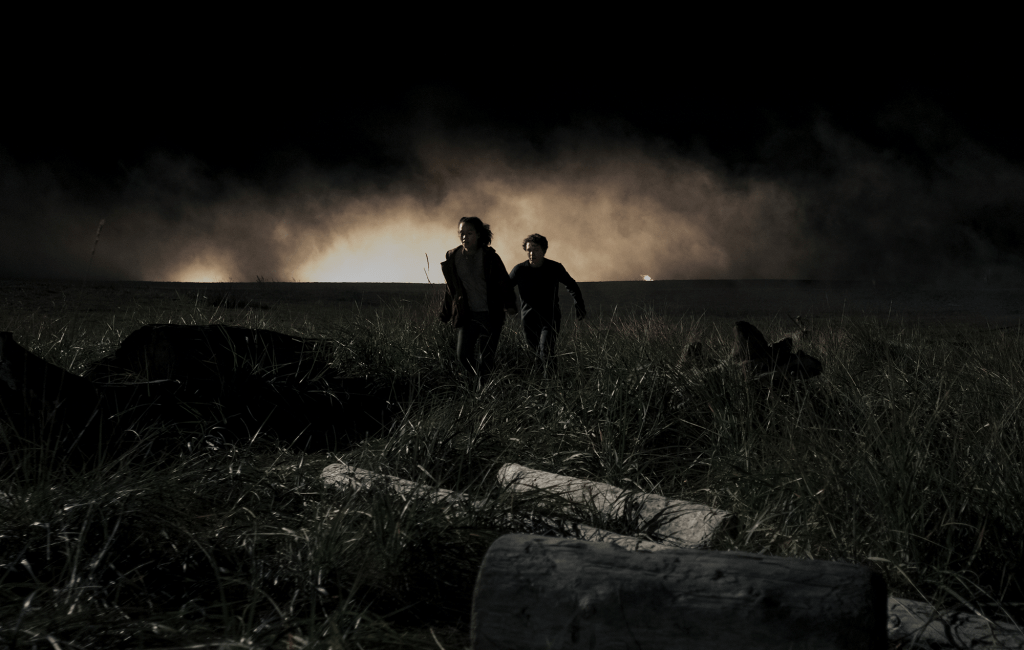

Every ounce of the film screams that there is a need for ritual to mitigate our losses – personal, social and economic (why the decline of fishing and ecological disaster in marine habitats matters in the film series). The absence of ritual being forever symbolised in waste lands where past human activity is represented by clutter from the past, right to the very end of the story:

‘symbolised in waste lands where past human activity is represented by clutter from the past, right to the very end of the story‘.

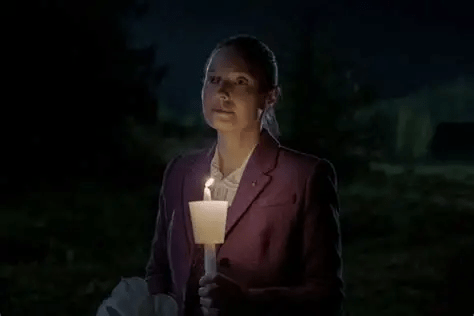

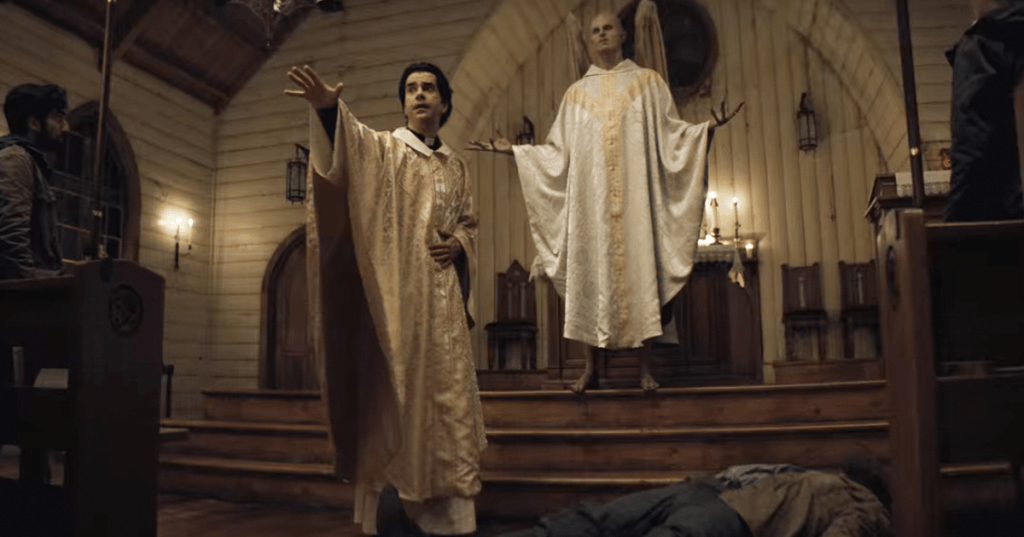

So even though the majority of the ritual of the film in each episode, is both fake and based on deceptive and hidden motives (the spread of vampire culture eventually to and through the mainland), it is presented as beautiful and positive even in the most evil of characters, like the priest’s self-centred (but replete in Biblical quotations) assistant, Beverly Keane (Igby Rigney). The most charming and sinister scene being the candlelit parade of the faithful calling out from their homes those celebrated to a ‘Final’ Midnight Mass, an Easter Mass celebrating the conversion of the body to everlasting life.

The candlelit celebration led by Beverley Keane.

The Church scenes with or without the Angel administering to them make more of ritual, where symbols like light are coloured by vestments, and the sacred objects and architectural shapes of established religion, even the charismatic fervour of the celebrant’s gestures and gazes reaching out to others – even to those others beyond the screen.

In one scene, priest Paul is haloed in a Gothic window:

And the face of the Angel is gilded like a statue representing religious allegory of the ever-open doors and heart of the Church.

It is a metaphor Bev Keane makes her evil own:

And wrapped up in the idea of ritual communion is the idea of doing no harm to children. The most painful instance of this is that Erin Greene’s body rejects the baby in her womb, because she has become more her younger fitter self, and it rejects continuity through another life ‘naturally’ because of the toxics in her body that redeem it (the blood of the vampire). But it is there in the constant reminder of young people having their lives in the care of the community – in families, in their groups learning how to work through teenage self-obsession, and in institutions (all of the Flynn family have been servants at the altar of the church).

But from the very start decency lies in the hope offered by the young, even teenage boys in teenage attire carry light, if only of a torch.

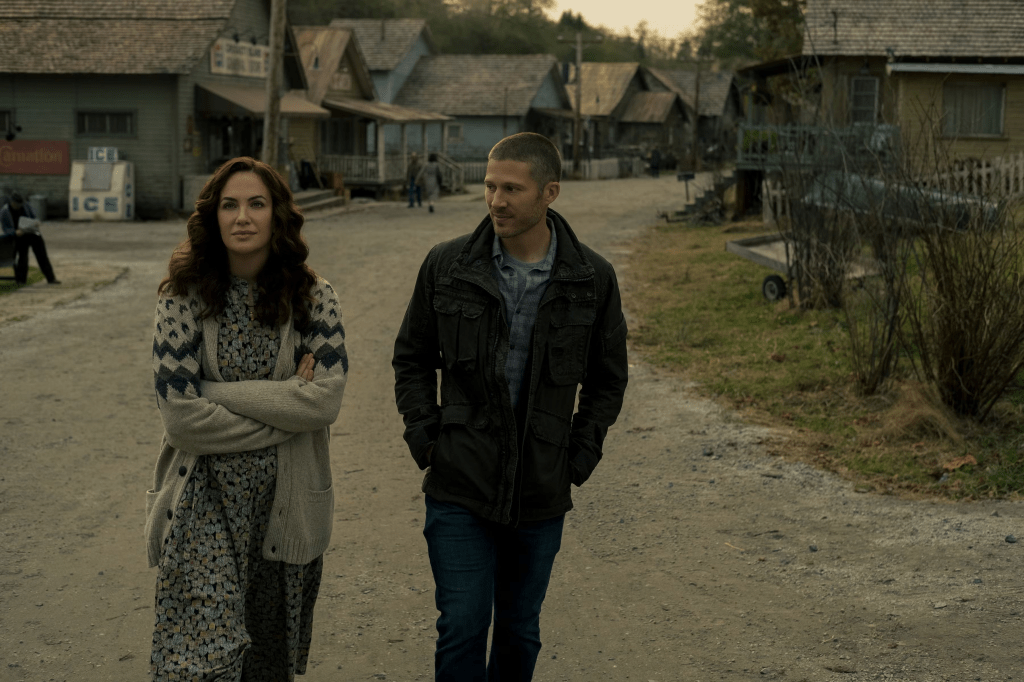

If hope is to come anywhere, it comes from the survival of one boy (Riley’s younger brother, Ed -Andrew Grush ) and Leeza Scarborough (Annarah Cymone), neither of whom take the final ‘sacrament’ of undiluted vampire blood. And though Leeza returns to disability at the end of the vampire’s promise of renewed life, the film leaves us in no doubt that their relationship mirrors that sacrificial relationship of Riley and Erin:

Ritual however is not treated as kindly as love. That seems to be the point of the inclusion in the story of Sherrif Hassan (Rahul Kohli) who had fled the racism and Islamophobia of the mainland only to find himself called ‘terrorist’ by Bev Keane, who lays his potential to breaking the communion of islan community to his insistence on the superiority, for him and his son Ali (Rahul Abburi) of Islamic ritual prayer – represented solely in the film by the use of prayer mats:

Even at the end of the film and the destruction, by Bev Keane’s folly and Biblical literalism, of the vampires created in the Easter Mass ritual, the Sherrif still kneels to Mecca. But Ali does not return to Islamic ritual – even having been shown how perverse the Christian ritual that attracted him was, but to a stance independent of ritual religion – in that like Riley Flynn and Erin Greene, whose God is entirely one of human story about humanity. As his father kneels, he stands – in awe but not in ritual obeisance.

Perhaps the most frightening and horrific of the sacrifices made to sustain humanity against loss of identity in symbols of supernature and/or religion, is Erin’s. It is a grotesque scene that deliberately recalls the most carnal of rapes as the Angel lies on top of her to drink her blood. As she screams she learns to pull the Angel in, forever increasing that supernatural beings thirst, to give her space to cut the Angel’s leathery wings as he is distracted in hunger for her blood and body. The scene is shot from above and shows the ritualistic symbols that cover the Angel’s naked back.

It is horrible yes, but think about it – Erin has discovered the Angel’s weakness uncovered by studying the manner of his enactment in false rituals, as below:

My own feeling is that film-maker and writer, Mike Flanagan, has been fired up to this film by what it has to say about the adoption of identity – communal like that of local community (even one bound by traditional occupations like fishing), sociocultural as in the identity of an institutional religion or ideological in the form of a kind of rigid belief in what is and is not ‘naturally’ human in our behaviour and has decided that what matters is neuronal pattern-making that renews people according to their best attainable and aspired for natures irrespective of social beliefs. This is not a bow down to science for even the ‘scientific’ explanations of Dr. Sarah Gunning (Annabeth Gish) are seen as inadequate to the case in the story, but to look for human myth in creativity – why I think its best articulations sound like Coleridge, the very best philosopher of the Imagination.

That’s all for now

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxx