Have you ever had surgery? What for?

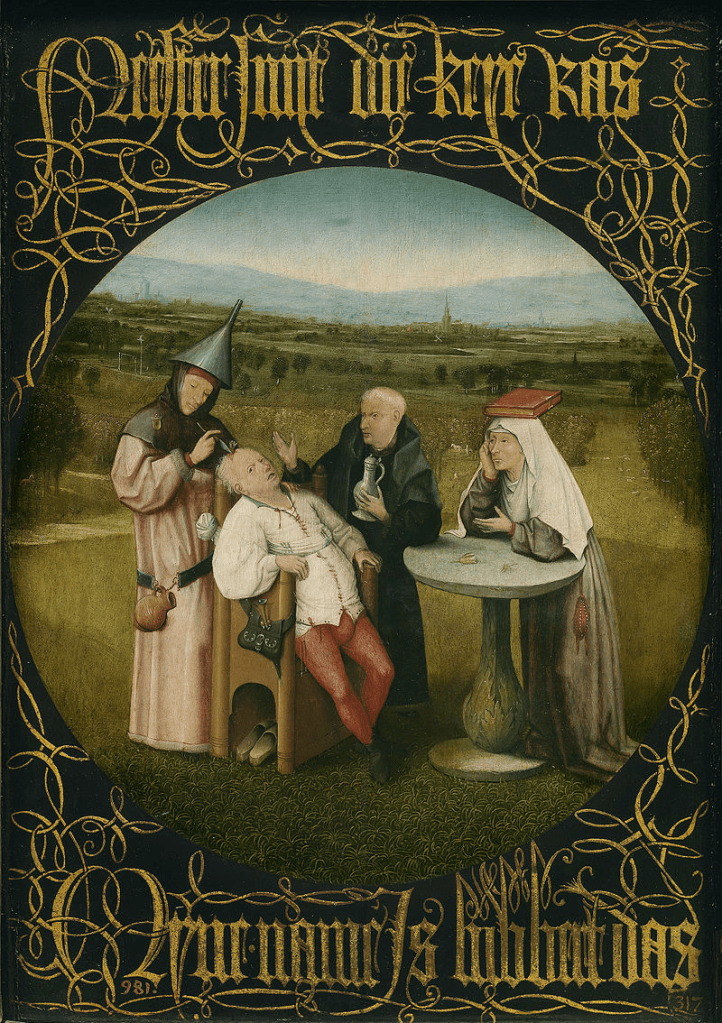

The Extraction of the Stone of Madness (The Cure of Folly) by Hieronymous Bosch

Let’s as usual start with the history of the word ‘surgery’ for it contains an important fiction. Here is that history, as usual from the invaluable etymonline.com:

surgery (n.): c. 1300, sirgirie, “the work of a surgeon; medical treatment of an operative nature, such as cutting-operations, setting of fractures, etc.,” from Old French surgerie, surgeure, contraction of serurgerie, from Late Latin chirurgia “surgery,” from Greek kheirourgia, from kheirourgos “working or done by hand,” from kheir “hand” (from PIE root *ghes- “the hand”) + ergon “work” (from PIE root *werg- “to do”).

Whilst no doubt ‘hands’ are directly involved in the setting of bones after dislocation or fracture, the modern meaning of ‘having surgery’ inevitably involves medical operates which involve major or minor incision – some kind of cutting of the body surface at some level – the skin of the gums in dental surgery, the ‘keyhole incisions’ of some modern microsurgery or full blown opening up of a cavity to the body. Indeed attempting to give a modern definition of surgery, Wikipedia, uses only the adjective ‘manual’ (obviously derived from the Latin manus meaning hand) to reference the hand, and then only when we intuit the hand carefully manipulating some tool of major incision (from a saw used to sever bones, to a scalpel (a surgical knife at base) and down to a needle using in sutures).

Surgery[a] is a medical specialty that uses manual and instrumental techniques to diagnose or treat pathological conditions (e.g., trauma, disease, injury, malignancy), to alter bodily functions (e.g., malabsorption created by bariatric surgery such as gastric bypass), to reconstruct or alter aesthetics and appearance (cosmetic surgery), or to remove unwanted tissues (body fat, glands, scars or skin tags) or foreign bodies. / … / As a general rule, a procedure is considered surgical when it involves cutting of a person’s tissues or closure of a previously sustained wound. ….

Nevertheless the myth of the subtlety of a ‘surgeon’s hands’ lives on, particularly in describing hands that appear capable of flexibility of movement, accuracy of application and a good sustained grip and hold. Mai Rostom, after training as a plastic surgeon remembers this idiom as even having an effect on her:

I remember when I was a young and budding doctor; people would look admiringly at my hands, smile knowingly, and say “you have the hands of a surgeon.” This was a wonderful compliment; it generally meant you had elegant hands, long nimble fingers, and soft, unblemished skin. They were not heavy labourer’s hands—surgeon’s hands were for delicate work, they were for making art . . . or so I thought. [1]

Yet from the very first operations in history performed by so called experts (thought to be trepanation – the making of a hole in the head to release some cause of madness), the royal road to their performance is the tool. Look again at the picture of such a surgery from Hieronymus Bosch above: clearly the skill of the surgeon still needed the save-all presence of a priest, lest what was released was a malignant spirit or demon. Bosch clearly satirises the whole procedure – the surgeon has an inverted funnel on his head to show the direction in which his own wits might fly, and knowledge is acknowledged only by a book carried on the head rather than in it.

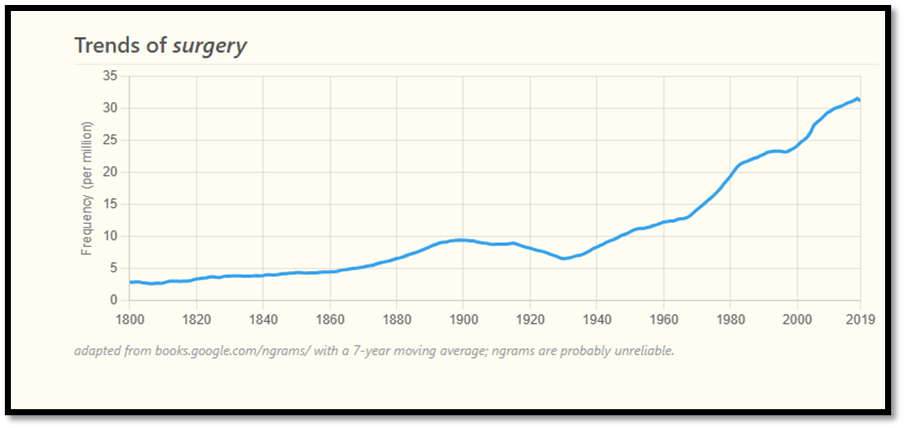

And even in modern history the use of the word surgery in the English-speaking West is most easily explained by the urgent repair of violence done to the body. A Google n-gram (above) in etymonline.com showing the frequencies of use of the word (n-grams are not reliable but might guide our thinking sometimes) shows usage peaking around the time when war became more mechanised and wounds more general from 1990 to 1820 (covering the Boer and First World War) then ballooning in use as the discoveries of surgeons are put to better use and there is more belief in anaesthesia.

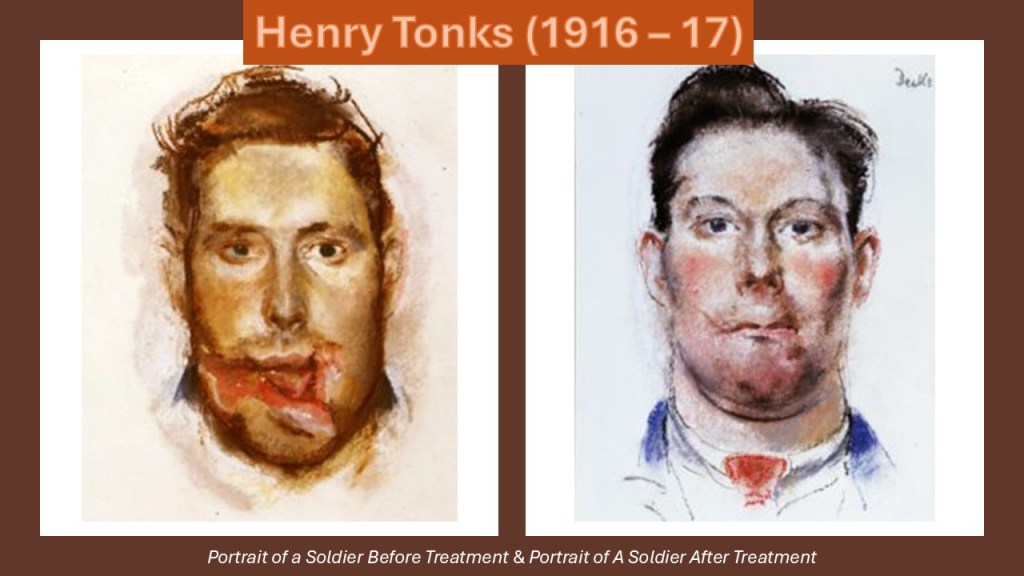

One vital area of surgery melded during the Boer and First World Wars with the purposes of art and the understanding of facial anatomy in both medical and artistic contests. One of the most famous areas being the work of Henry Tonks, the head of the Slade School of Art who made a specialism of before and after paintings of bad facially wounded soldiers.

Pat Barker wrote on of her most neglected but fine novels, Toby’s Room, that focused on Tonks, art and war – and the philosophy of surgical plastic medicine.

But nosy old WordPress insists I tell all about personal experience as usual. In fact for me all of this work has been dental (as in the blog linked here which tells the story of one of those experiences).

There was however more to come in that same story. The pain I felt from that incision continued and developed for a further three months, during which my own dental surgeon’s indicated rather consistently that my pain was psychosomatic – would after one try prescribe no antibiotics or strong painkillers, and I lived on Paracetamol and Ibuprofen in series – then not dealing with the pain which extended from my throat, to nose, ear and to severe headaches. Eventually my local dentist referred me back to their private surgeon, again at Brampton, and this time my husband took me because I feared driving with the pain.

The dentist operated again removing another tooth adjacent to the site of the wisdom tooth and then scraping out decay left in the old wound of the wisdom tooth which had caused the original pain. The sensation of scraping and cutting could not at the time be felt as pain – being heavily anesthetised locally but later it was horrendous for at least three days. After three months of pain, you trust the skill of no-one’s hands and I had to get better to trust again. And of hands – skilled or otherwise – I remember very little – just the look and feel of cutting, gouging and scraping tools.

All for now.

Reading Saraswati for my next blog. Much more wholesome.

With love

Steven

[1] Mai Rostom (2014) ‘A surgeon’s hands’ in BMJ 2014; 349 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1892 (Published 04 August 2014): BMJ 2014;349:g1892