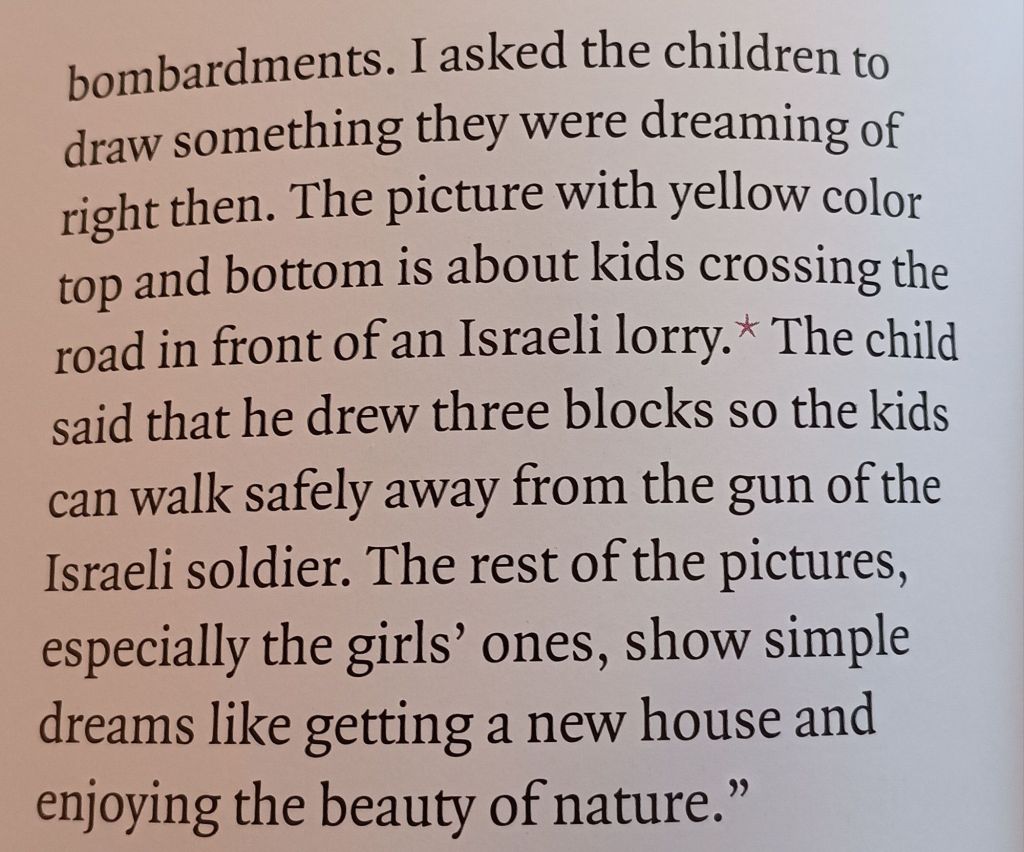

One librarian at the Tamer Library, Haneen, interviewed by Robinson and Young devises activities for 8 – 13 year-olds in the area of Gaza where the Institutuon stands. When asked about their future lives, Haneen considers that the older children think mainly of emigration from Gaza, whilst ‘younger ones, without older siblings, do not think about the future. They think about the here and now‘. In fact, however, the evidence she presents of children’s art (obviously before the worst excesses of the current genocidal assault on Gaza by the Israeli Denfense Forces [IDF]) shows a slightly different view, which allows girls to imagine a future of flowers and a new home whilst boys tend to stick in a conflict unless present. To analyse that difference would take a whole book on diversities in child developmental psychology, but look at one boy’s drawing of what he might dream of in a future world, given the instructions from Haneen: [1]

Imagining a future where blocks appear as if by magic to shield a single child crossing a road in front of an armed lorry is a rough vision of future hope but it tells a chilling story of who really has a future outside of magical thinking. I think Piaget may never have imagined the use of such thinking for this purpose, even in pre-operational cognition.

When I looked for reviews of this book I had the ill fortune of stumbling on one published by the pro-Israeli propaganda group the group the Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting and Analysis (CAMERA). Just as hegemonic ideologies often present themselves as the home of the non-ideological, this group presents a view of the world past, present and future governed by the presumptions of ideological Zionism (often that of a minority right wing view in Israel itself) that represents Israel as the hub of the project of establishing stability and security under the command of a nation that pretends to God-given historical legitimacy. It is an ideology precisely because it lives in a ‘divine’ promise and eternal right, justified by the terrible suffering of the Holocaust, of a future that is eternal and unflinchingly secure for Zionist supremacy in the Middle East.

That kind of Zionism has, since establishment of the Jewish state and the creation of the IDF from the remnants of the right-wing terrorist group Haganah, tied itself to the interests of the capitalist West, just as was predicted by the groups of freedom movements from Ireland to South Africa. CAMERA’s reviewer, Marjorie Gann presents herself as a champion, conceptually akin to Jean Jacques Rousseau, against those intent on souring the minds of the young with ideology:

There is a maxim, often attributed to St. Francis Xavier, one of the founders of the Jesuit order, that reads: “Give me the children until they are seven and anyone may have them afterwards.”

In recent years, authors writing about the Arab-Israeli conflict have set their sights on children both younger and older than seven. Like the Jesuits, their aim is to shape the minds of the young. If the Jesuits’ goal was to turn children’s minds towards heaven, theirs is to turn young readers against something more earthly – Israel.

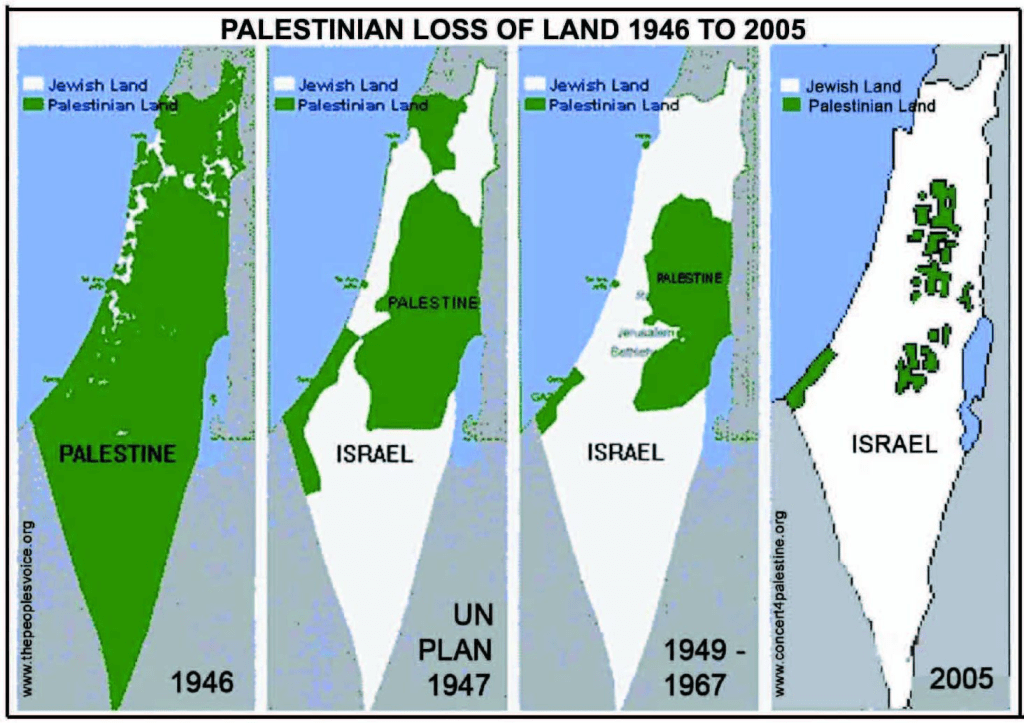

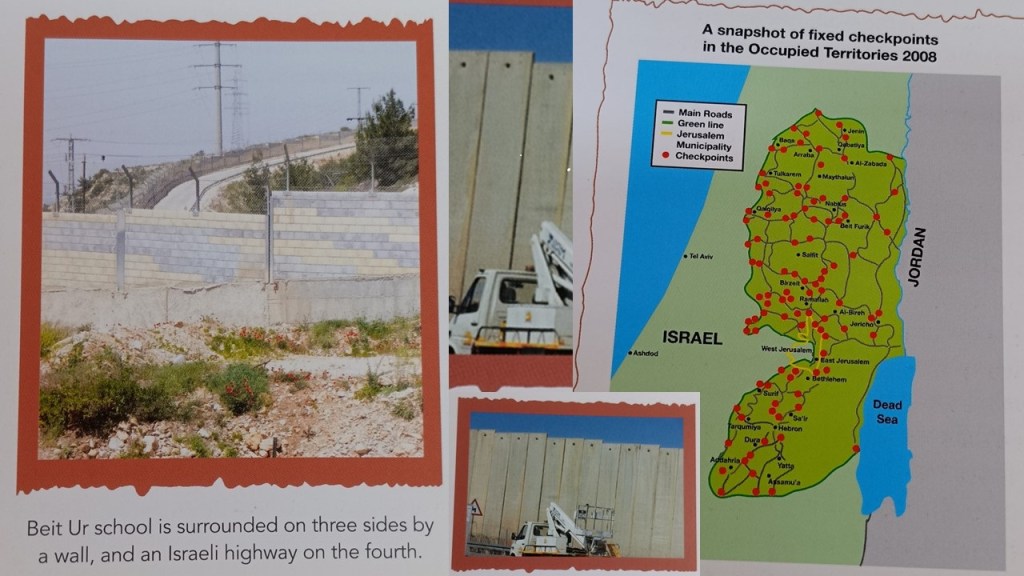

Now this representation of the book sees it as part of a social movement which Gann believes is rooted in Antisemitism. She argues that the book presents ‘facts’ that are indeed actually ‘lies’ (no messing about with nuance for Marjorie) especially in the construction of maps that promote these lies (the ones she picks out are below) and says:

For the naïve, ill-informed young reader, these lying maps tell a simple story: Starting in 1947, Israel (or the Jews) grabbed more and more “Palestinian land” until there’s almost nothing left in Palestinian hands today. That is exactly the message the authors of Young Palestinians Speak want young readers to come away with.

In fact the maps really represent only the growth of the land claimed by Israel to represent ‘Jewish land’ in the context of the area called Palestine under British mandatory rule. There is no pretense of an original unity of land called ‘Palestine’ only a representation of how the state identified lands that it claimed the right to name Israel and establish Israeli law, including those laws which reduced the rights of non-Israeli citizens (Christians, Muslims and others). She claims the borders aren’t real borders, but contingencies of past struggles, and rightly subject to incursion in the interests of Israeli ‘national security’.

Moreover, leaving aside Gann’s representation of children’s minds as ‘naïve, ill-informed young’ (a rather sad view of child psychology from someone on the executive committee of ‘The Association of Jewish Libraries–Canada’ and ‘ a frequent reviewer of children’s books for AJL News and Reviews‘) I think the interesting part of this review is that she never once looks at the words of the young people that are the meat of this book, only at its editorial framing and the views there from people she represents as scheming anti-Jewish adults – especially contending that the collected views of young anonymous Israeli soldiers must per se be lies if they see injustice in the roles they are asked to take on, without considering why some Israelis do not want to bring their identity to the attention of the state.

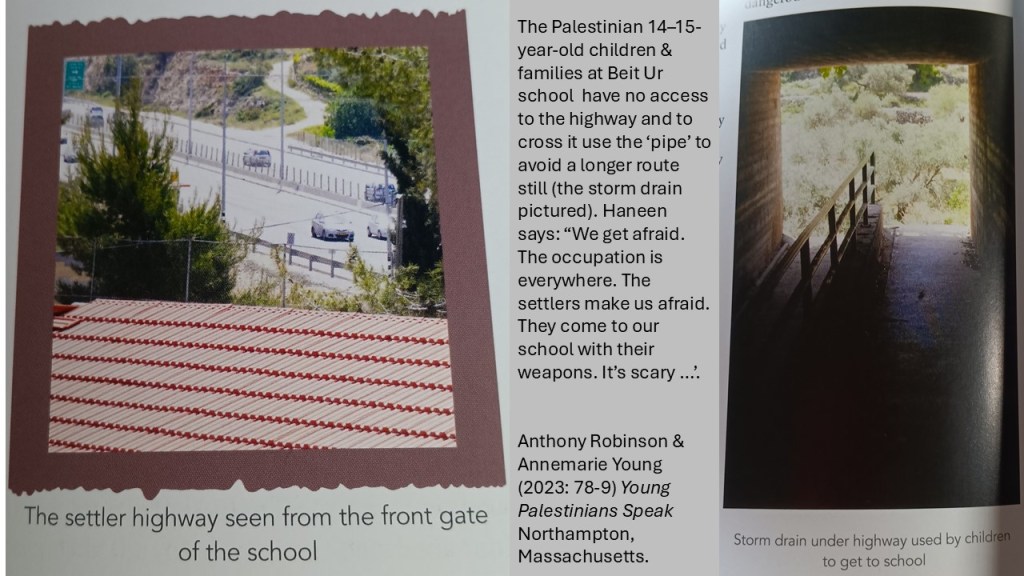

The core of this book lies in the fact that the children seek to represent their future in one way or another (as in preoccupation with the here and now or ordinary dreams of ideal careers – and sometimes of living in a free state) as an escape from their present – in Gaza in particular, whose every border, including the sea – is guarded by military presence and was so even before the border incursions into Israel and murder of over a thousand Jews randomly selected by virtue of their nearness by Hamas extremists. Whether Gazans have a future as Gazans now is uncertain. Many young people describe themselves as yearning for freedom of movement outside of confined passages of transit or within security walls, even the ‘prison’ walls that were the borders of Gaza or the eternal building of ‘Separation Walls’ (an idea from apartheid administrations including once, Northern Ireland):

‘Separation Walls’ are a necessity, says Gann because of security from terrorism. Settlers rights guarded by the IDF are to be protected, even whilst not officially validated by the Israeli state, even when the rights of building and movement are heavily restricted for non-Israelis. That isn’t the case for Jewish settlers outside established Israeli ‘borders’, who are given a kind of self-validating legitimacy guarded by the IDF. The United Nations is seen as the arm of anti-Zionist global bias.

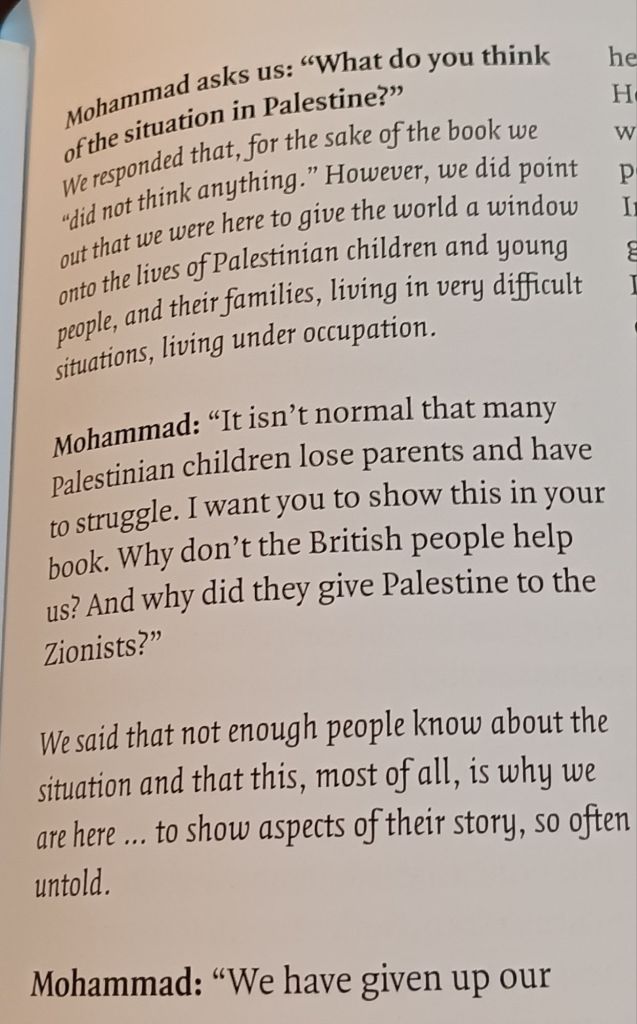

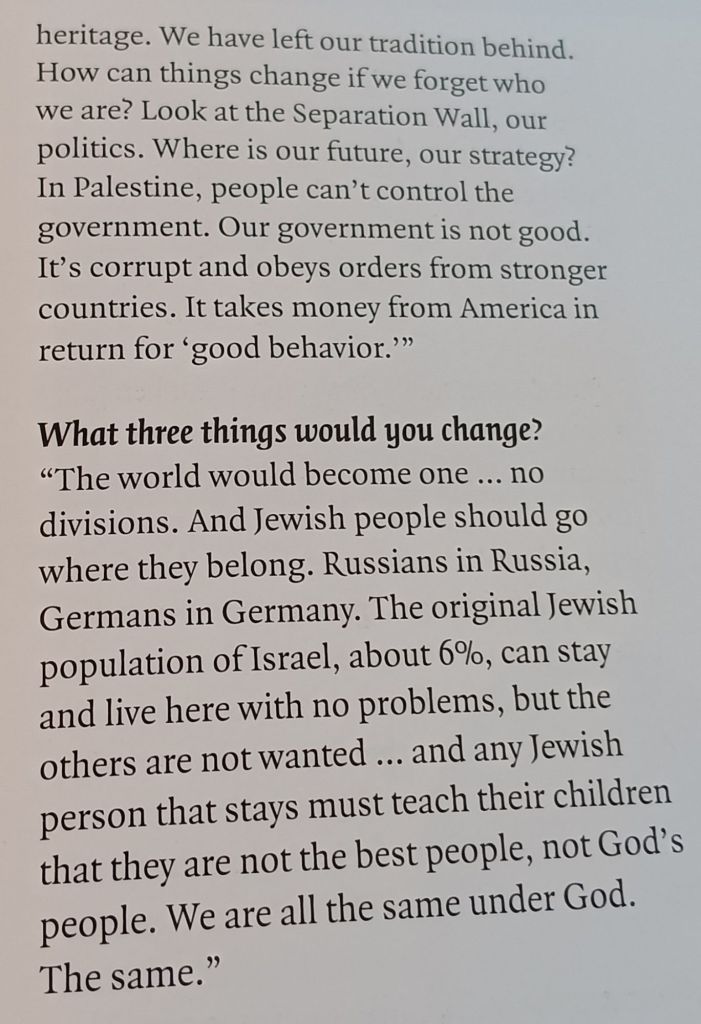

The authors themselves are transparent about how they guard the book from being a record of their views but of young people. At 17 years of age, however, Mohammed distrusts such shows of neutrality and quizzes it. The authors, however, insist on refusing to commit the book to his views. Those views are clearly developing into a manner that is antagonistic to immigrant Jewish settlement [3]:

Of course to Marjorie Gann the word ‘occupation’ is already a ‘lie’, though her evidence for lying is really that for ‘inaccurate’ definition – the Israels never intended to take Arab areas into their control, she argues, but were forced to by attack from hostile Arab regimes in the Six-Day War of 1967. On the basis of using a poor definition, Gann dismisses not only the authors but all of the young people whose family experience – of legalised (by the laws of the Israeli State) imposition of restrictions on movement of land development or access to civil law redress, relatives imprisoned or forcibly evicted, of arbitrary powers of search and arrest, the role of life-disrupting checkpoints at barriers in walls or tunnels – leads them to use this term, without prompting by the authors, too. Nour, a boy of 14 talks if his family life as ‘not living. We survive., and Samia, a girl of 12 describes occupation as an effective prison: ‘The occupation. It fills our lives. We cannot escape it’. [4] The children of Qattana have to go to school through a small tunnel they call a pipe, for it surges in floods, because their land was sequestered to build a separation wall in order to guide settlers subject neither to Israeli or Palestinian Authority (PA) law but autonomous and yet guarded heavily by the IDF. Times for schooling have to be changed to avoid the children getting harrassed by settler children:

Now we can disbelieve these children’s stories, call them brainwashed by their interlocutors, teachers or their families or just believe that children being ‘naïve, ill-informed young’ people know no better – especially than older people paid by the Israeli State to correct their ‘inaccuracy’, even outside Israel. But that is yet another reason why the editors believe that young Palestinian people lack the ‘opportunity to speak and be heard, or if they are unable to speak’ for someone ‘to do so on their behalf’.

If they can’t speak how can they describe a future fit for them when they have so little power to being their future in any shape into being. Largely the book argues that these young people want what their peers want including ‘a space in which to grow up and dream of a future’. [5] Too many futures in this book end with a Separation Wall or a checkpoint where access is not ever guaranteed.

And if you listen to these voices, though there is accumulated hate for the occupier in some, whose history of eviction and limited rights, or of the death or imprisonment of family members is high, there is also a desire for a non-sectarian future and some criticism and a need for ‘better leadership’ or of arenas in which: ‘We are fighting ourselves’. [6] This book was finished before the worst of the Gaza genocide but even then it was clear that hope for change – in brief a ‘future’ – was not one these children looked towards. Futures depend on some security experienced in the past but listen to Abel Aziz, who is 16. [7]

This book needs reading, though it feels tame if you were really to listen to current experience in the West Bank, and so much more in Gaza. Had I answered this prompt to say what I am ‘worried about’ in my future, the sense of entitlement would overwhelm me.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

___________________________

[1] Anthony Robinson & Annemarie Young (2023: 73-5) Young Palestinians Speak Northampton, Massachusetts. Bold & italics are my emphases.

[2] For Piaget on magical thinking, see: Magical thinking | Psychology & Cognitive Development | Britannica https://share.google/Nc5zoXXRcpvB4yOeM

[3] ibid: 39

[4] ibid 15 & 13 respectively.

[5] ibid: 7

[6] ibid: 64 & 72 respectively

[7] ibid: 42