“Can you decline history”(! Or ?) [1] The meaning of Getrude Stein’s life, writing and relationships might lie in the fact that we do not begin to determine our futures without, in one way or other, deciding how we re-member and then revise the fragmented biographies of ourselves, others and our group histories. Can revised histories or memories be maintained without asserting power and control over rebellious voices who question their authenticity? The deep soil out of which a new biography of Gertrude Stein grows concerns us all: Francesca Wade (2025) Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife London, Faber.

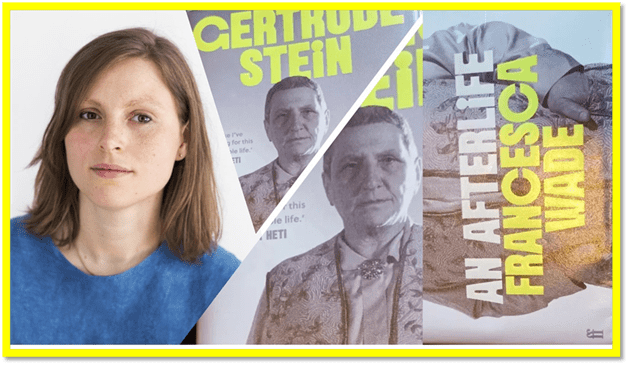

I read Francesca Wade’s biography neither as a result, nor as a prompt, to reading reviews of the book, although on seeing the book I was intrigued by biographer Edmund Gordon naming it, in his comment cited on the back cover that it was: ‘Not only a tour de force of biographical writing but also a breakthrough in biographical form’. After reading it, I felt I knew exactly what he meant, but I also realised that another comment on the book, on its front cover by Sheila Heti, was probably a more accurate pull-factor for me with this book, for Heti says: “I feel like I’ve been waiting for this book my whole life”. That is because, although I think the book indeed does break ground in turning reflection on the nature of biographical history into a new form in which to write that kind of history, for me it did so best by making me review how knowledge of Gertrude Stein was interwoven into my own life-history.

But having finished the book, and heaved a gasp of awed admiration, I have looked at two reviews, before giving up wondering whether there was something implicit but inalienable in the contemporary culture of reviewing that made such consultation a mistake. Book reviews are a recent invention, deriving I suppose from the increased commodification of books from the eighteenth century, acting as a means of mediating between the book production industry, amongst whose personnel are only one type of the necessary turnings cogs out of which books come, and the consumer of books, the ‘reader’.

Of course this is a complicated issue in truth, for reviewers tend also to have a range of relations to the literary academe, that pretend in some cases to the refinement of taste for reading into a specifiable area of knowledge, skills and values that pretend to objectify what is meant by good writing that does more than tickle our taste buds. For either reason (as a consumer-guide in the book market or a reader refined into specialism by academic training – and sometimes current status) reviewers feel entitled to get between a reader and the book – sometimes to the effect of stopping it having any readership at all. They deliver their judgements most often with clear ambivalence, like Kathryn Hughes in The Guardian on this ‘thoughtful and deeply researched book’ in Hughes correctly admiring words. It is a mixed bag though, Hughes says, because Wade:

spends half her lengthy text retelling Stein’s very well-known life, from the early days as a medical student in Baltimore to the last scary years hiding out from the Nazis in the French countryside (although they seldom acknowledged their Jewishness, Stein and Toklas knew that they were at high risk of being sent to a concentration camp). [2]

Not until page 204, she continues, does Wade really embark ‘on the more interesting and original aspects of her investigation’, and, in the process revises both how we should read Stein’s most read popular work The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, and the life-histories behind it:

Far from being a celebration of a serene and settled relationship, it now looks as though the crowd-pleasing classic was composed by Stein in a desperate attempt to keep Toklas from storming out after one provocation too many. But if Wade had written a shorter and more focused investigation of Stein’s posthumous reputation, perhaps it would have showcased her achievement to even better effect. [2]

How quickly do we here slide into the perceived limitations of Wade’s ‘achievement’: marred it seems by telling a story already well known instead of moving straight for the fruits of the book’s research. Hughes’ response needs further consideration later, for I think she misunderstands why it is necessary to retell the networked history of both Toklas and Stein behind the Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas in Part 1 of the Book before the effect of later research of the ‘afterlife’ is revealed in the revision and reconfiguration of those lives in Part 2. Moreover, I think she is just plain wrong to think that Wade’s purpose is metely an academically conceived ‘focused investigation of Stein’s posthumous reputation’. The last phase stinks of the modern academy.

In a sense, Hughes misses the main point of the book when read as a thing that cares about the human materials it discusses; which is about the revision of all kinds of history as a function of the passage of time. Too keen to look like what she thinks a critic should be, and balance the good and strong with what she see as the weak or ‘not-that-good’ in the book, the book essentlly matters as little to her as the thoughts and feelings of the real people who once existed and are its subject matter do.

Bur Hughes’ response is at least one up on The Observer commentary delivered by Rachel Cooke. The latter clearly feels she has already sussed Stein and found her more than wanting, despising what she sees as Wade’s naivety in not seeing how obviously unserious Stein is as a writer. Cooke says:

Wade takes Stein seriously at all times, … As she said herself: “I write to write.” Her apparent desire to shed language of all its associations so her own words mean something entirely new is batty as well as egomaniacal, mere gibberish next to her rival, Eliot (“Why is a feel oyster an egg stir?”).

In the end, for all Wade’s determination, you find yourself with Virginia Woolf, whom she tried to persuade to publish her modernist saga, The Making of Americans, under the auspices of the Hogarth Press. “We are lying crushed under a great manuscript of Gertrude Stein’s,” Woolf wrote to a friend. “I cannot brisk myself up to deal with it.” [3]

Accusations of egomania are not unmerited, perhaps, in a woman who was determined to defend herself from those who found everything about her outside the norm – not only her ideas, feelings and behaviour but her self-conscious American feminist lesbian Jewish identity and the new templates in language she sought to express both her singularity and the fragments of her identity at war with each other. Such contradictions included , as we shall see, some thoroughly unlikable traits and errors of judgement held in principle (on politics in particular such as those that engaged positively with the obnoxious Pétain regime at Vichy during the French Occupation by Germany in The Second World War). But Cooke is not in a position really to justify not taking another human being, even if a dead human being, seriously and to base her judgmental sub-articulate-vocabulary on such thin evidence – one quotation from the millions available from the works of Stein, even the more grammatically awry ones. But let us leave Cooke stewing in her own malign juices!

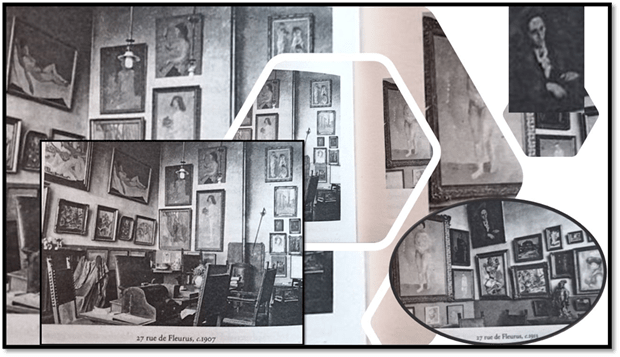

Eventually, it is my aim to show that Stein was unlike every other person (mainly male but including Virginia Woolf too) who claim to be re-configuring the language of literature in the interests of the fresh, new and a world that no longer believed easily in supposed ‘verities’ that specialist and unchanging canonical notions of family, church , state and person – verities like God, Providence and other prescribed essences. This is the world of the writers soon to be called ‘modernists’ (and was first exhibited to guests in the clutter of the Stein home).

No-one invoked the modern as a standard as much as Stein and no-one as consistently as Stein. this is one reason she disliked the fact that eventually, every issue to be solved by modernism was attributed to writing by James Joyce, Ezra Pound, and T. S. Eliot. Their solutions she argued was backward-looking, not just in national politics (for in that she had her Republican conservatism intact) but in terms of literary form and linguistic method – often relying for effects on past associations evoked by their language.

Wade shows that what really hurt (and angered) Stein was that her rivals were supported by avant-garde publishers and literary mentors in ways she was not. [4] This was despite the fact that only she knew (‘egomaniacally’ or not) that only she was reinventing language by attempting to eradicate the grasp of the past on it. Whilst they evoked old models and modes of relating (perhaps) and the language that goes with it (even as they innovated), she did not. It made her hostile to Joyce with his constant recourse to old literary models with which to parallel his modernity, and in her view, compromise it:

You see it is the people who generally smell of the museums who are accepted, and it is the new who are not accepted … It is much easier to have one hand in the past. That is why James Joyce was accepted and I was not. He leaned into the past, in my work the newness and difference is fundamental. [5]

Stein’s challenge to the past is not based on ignoring it but in making it serve progressive futurity, especially in the realm of character and identity and this applied to the way she formulated her response to her Jewish background, her sexuality and her grasp of gendered being. The point is not hankering after ‘tradition’, as in Eliot, but in reformulating memory of the past for the purposes of a present as it progresses to the future.

Again I will argue this more fully but here I need to digress, for this book felt wonderful to me because it reread even that part of my history that related to attempting to know the work of Gertrude Stein. My first memory of reading Stein was related to taking classes – offered in his own time – by out teacher at Holme Valley Grammar School in the 1960s, who provided us with a reading list for Special level English exams. On it, I remember, was a reference to only reading Stein’s Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, because the rest was, he inferred, not worth the time it took to read it.

This was very much the critical view of the period and it is one that persists, and was even prevalent in her earliest reviews (where they existed at all). As Kathryn Hughes says: ‘one relieved critic noted at the time, Gertrude Stein had finally started making sense’ in the Toklas ‘autobiography’. Rachel Cooke, though claiming that this book is more admirable even than Wade’s first well received group biography – focused on Bloomsbury – so dislikes the art of Stein that even of Wade’s praised book, she says: ‘I cannot say that I really enjoyed this book’, despite the obvious hard work and intelligence ‘wasted’ on it.

For me this book freed me from my prior bias against Stein’s significance, relative to the contemporary Modernists (one confirmed throughout my academic training) and placed Stein in the category of the persons grossly misrepresented by history. However, this was not the first time I had felt that very thing (though then for a short time) because revivals of Stein occurred through the confluence of my own history and that of Stein’s ever-fluctuating reputation.

I remember, for instance, that period described by Wade where Stein was suddenly seen as a proto-Fascist pariah (as even antisemitic in turning a blind eye to the fate of fellow Jews not as well connected as her). Like others, I was influenced a lot at the time of my undergraduate education by the version of Stein by Janet Malcolm, who with others made much of Stein and Toklas’s connection to Bernard Faÿ, apologist of Vichy, friend of Pétain , and extemporizing historian of that movement and man, involved with some of the oppressions that Vichy mounted to curry favour with the Nazi occupiers in Paris. Wade deals with this brilliantly – but read that for yourself.

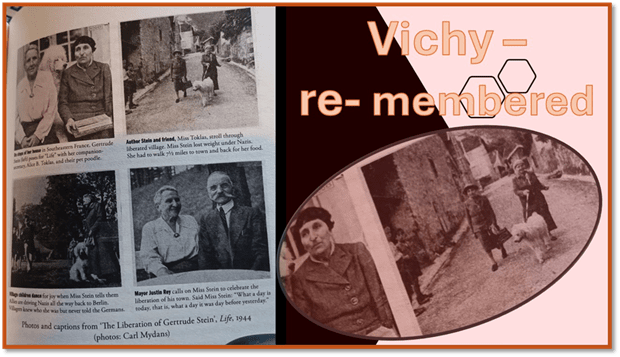

It was Bernard Faÿ that persuaded the Nazis to delay deportation of Stein and Toklas (which would have ended in concentration camps) and to not (at least yet) sequestrate the valuable art they owned. But he did so by virtue of collaboration and had promoted Stein’s project to translate the speeches of Pétain into English for an American audience. Most feel that the accusation of attraction to Fascism ill-founded and her collaboration treated with too little nuance – though the same accusations pursued, with more justice, President Mitterand at the time. The collage below shows how, following the fall of Vichy and German defeat, Stein attributed her escape from Nazi persecution to the good faith of the village that took Stein and her wife to its heart – whilst fully aware that they were both lesbian and Jewish.Yet I remember all this causing distance from Stein’s work for me.

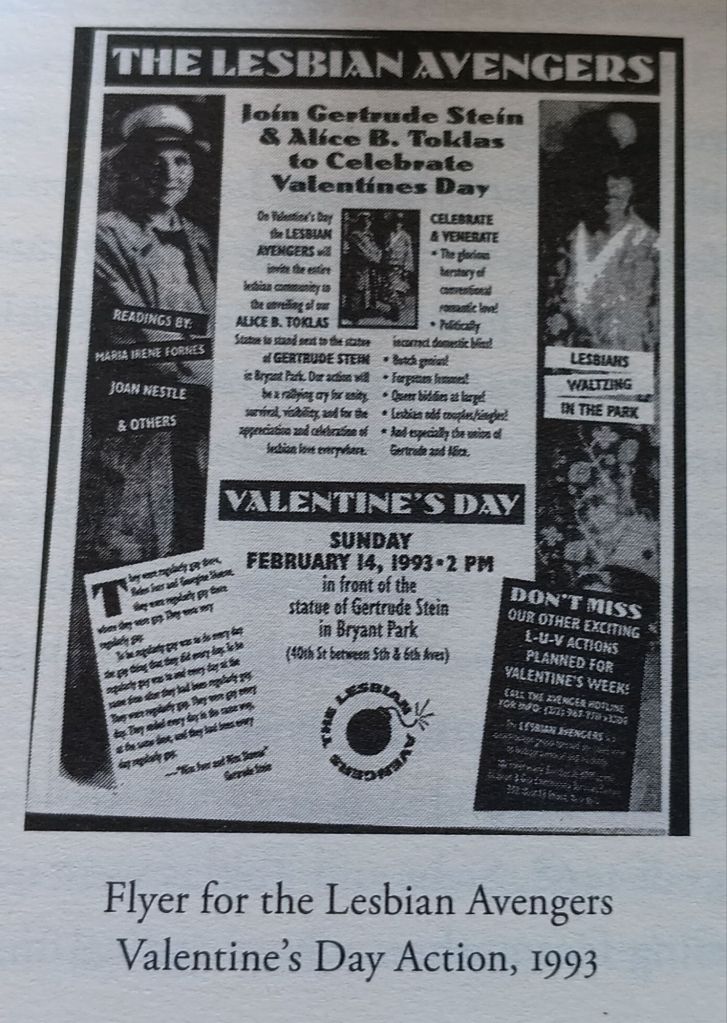

Almost simultaneously I began to see Stein at the same time not as a far-right collaborator but a queer ally, her cause taken up across the LGBT movements of which I was part. Wade reminds me of that moment in ways that touch me deeply: talking of activist energy, which, though largely in the USA, was reflected in London gay liberation thinking and in the heady alliances between feminist, lesbian and gay male movements towards a shared end. She writes of the Lesbian Avengers Valentine’s Day event of 1993, which I remember by report, as if the Stein/ Toklas relationship totally supported Gay Liberation’s attempt to renew romantic models of relationship in queer terms. Using this lesbian couple as its masthead as well as the problematic idea of that being between a ‘butch genius’ and a ‘forgotten femme’, they held them up to an audience tjey had never previously had in public [7]

At the time I wore in my seminars my favourite badge: ‘Gay Love: It’s the Real Thing‘ a spoof on the idiom of the Coca-Cola advertisments:

And it is that historical contingency that today makes me honour the way Wade creates a model for the biography of queer love. Because at the ‘heart’ (in both senses of the word – even its non-Steinian ’emotional association’) Wade’s biography hinges in its two parts on the manner in which Stein’s linguistic innovations mirrored the need to rethink the very negative associations of romance with heteronormativity. I tried to address this in an earlier blog on The World Is Round (see it at this link). The evasion of heteronormativity in that story may even be deeper than I recognised and certainly reading Wade helps you see that it is not entirely fanciful to see the connection of Sir Francis Rose, in his youth, with these two lesbian mentors as a spur to his creativity. Even after Stein’s death, Rose feted the boldness (to the point of embarrassment) of Toklas in 1960 as a domestic goddess. Note the cartoon below, entitled “Mlle Toklas fait le marché rue Christine‘: Everyone else fades in relation to Toklas, even himself, whom I take to be the young man behind her laughing embarassedly at Toklas pointing imperiously at the young girl’s melons.

According to Wade, the work that stands aside from Stein’s more innovative language and textual experiments, though it explains some of them as I said in an earlier blog (see this link), because it was targeted at the repair of the love relationship between the two women – a thing often tested by Stein’s imperious demands and the refusal of Toklas to assert her own independence in the shadow of Stein. What the book tells us that the history of queer relationships is a complex one to tell – that it continually requires rewriting not only of its prospects for the future but its grasp of the past.

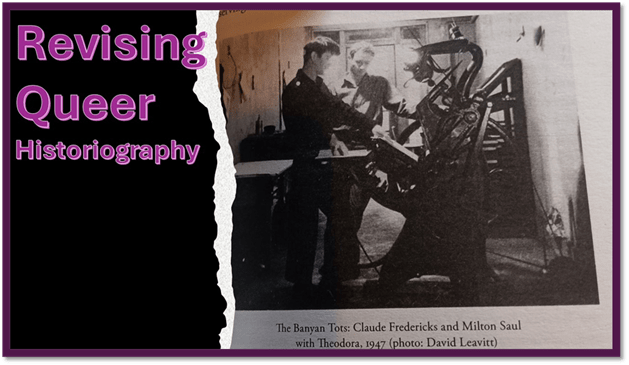

Some aspects of that are terribly painful. Not least how both lovers dealt with their differing sensitivities to Stein’s very early affair with the socialite May Rosenshine, even with the early novel QED that Stein wrote as a means of understanding her historic attachment prior to Toklas, and one that took precedence as Stein accommodated herself to Toklas’ own difficult personality, and (unknown to Toklas until she was shown the piece by a later would-be biographer) complained about that personality in bitter terms, calling her not only ‘cold’ but manipulative. Queer relationships are supported far less than heteronormative ones – and novel relationships less too than homonormative ones based on coupledom – and their history will often be rewritten. There is an excellent example, for instance in the relation of both Stein and Toklas with an idealistic couple, known as the ‘Banyan tots’ because of their ever-apparent boyish youthfulness, starting off with a printing project from their own home and keen to publish Gertrude’s works.

Yet before a significant achievement in their project, the couple formed by the idealistic youths split in two: the head of Claude turned by the cosmopolitan queer poet James Merrill (see my blog on him at this link). It is now ny conviction that Stein had a very profound understanding of how culture might support novel relationships with no past scripts to rely on (outside anyway of rarefied literatures) and the better for that since they negotiated love bonds as new and different not as something with the ‘smell of the museum’ [as in the traditions of heterosexual romance] in writing or drawing. The phrase ‘Can you decline history’, comes from Stein but is quoted in terms of its application to the handling between them of the contingencies of their continuing love affair – a ‘marriage’ but an unrecognised one, and perhaps one refusing that traditional label.

One reason I have for asserting this is the passage from the book I cite in my title. It comes from the time when the lovers organised their coming together, paradoxically by working not on Alice’s justifiable feelings about May Bookstaver, because as yet she did not know of that earlier liaison in Gertrude’s life., but rather Gertrude’s unwarranted jealousy regarding two female friends of Alice’s, Lily Hansen and Nellie Jacot. Read the following passage [8]:

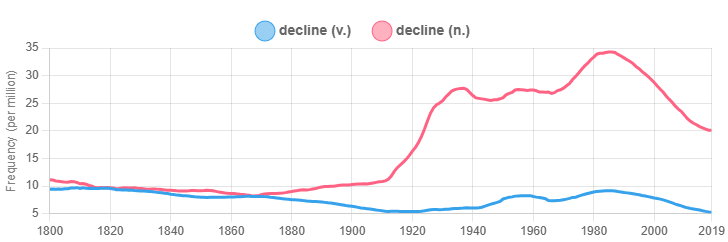

Of course, Wade is correct to say the phrase, ‘Can you decline history’ refers to the act of declension, the way grammars inflect nouns in relation to their use in the syntax of a sentence. But Stein never uses a word without full awareness of its multiple potential meanings, and the verb ‘to decline’ has varied meanings. The thin evidence from Google ngrams about its usage suggests that it also response to sociopolitical trends, rising in frequency as a noun from the end of the nineteenth century as perhaps a response made by societies aware of increasing pace of social change (social democracy for instance in both class and sex/gender terms), and its tendency to interpret its response as the fear of a fall in social standards. As a verb, it never reaches usage levels, though apparently more in use in the twentieth-century.

Interestingly the noun in the sense meaning a ‘graduated fall’ in the frequency or level of something came from a root in an old French verb according to etymonline.com:

decline (n.): early 14c., “deterioration, degeneration, a sinking into an impaired or inferior condition,” from Old French declin, from decliner “to sink, decline, degenerate” (see decline (v.)). Meaning “the time of life when physical and mental powers are failing” is short for decline of life (by 1711).

The verb tended to use other meanings of the early source that was less associated with a change to a falling state but rather any deviation or swerve from an established norm or level (up or sideways for instances) and became associated with turning or inflection, hence the appropriateness of the word to describe the transformations of nouns or their adjuncts (such as adjectives) in most languages sensitive to syntactic value – when a noun is used as subject or object of a sentence, or as referring to a possessive case (or as a plural – one of the few inflections in English language):

decline (v.) : late 14c., “to turn aside, deviate” (a sense now archaic), also “sink to a lower level,” and, figuratively, “fall to an inferior or impaired condition,” from Old French decliner “to sink, decline, degenerate, turn aside,” from Latin declinare “to lower; avoid, deviate; bend from, inflect,” from de “from” (see de-) + clinare “to bend” (from PIE *klein-, suffixed form of root *klei- “to lean”).

In grammar, “to inflect as a noun or adjective,” from late 14c. The sense has been altered by interpretation of de- as “downward;” intransitive meaning “to bend or slant down” is from c. 1400. Sense of “not to consent, politely refuse or withhold consent to do” is from 1630s. Related: Declined; declining.

Stein, ever sensitive to the use of words uses it as a transitive verb as it is used in this phrase ‘Can we decline history’ to play on every meaning of both noun and verb, especially its use in ‘polite’ (usually meaning in a class-based usage) registers of English’ as indicating a refusal . These are the usages of the transitive verb registered by Mirriam-Webster (the irony being that in using ‘history’ as an object rather than subject noun one has already declined it grammatically, even though in English there is no change in the inflection of the noun:

- 1a: to refuse especially courteously decline an invitation (declined to give her name to the reporter)

- 1b: to refuse to undertake, undergo, engage in, or comply with: decline battle

- 2: grammar : to give in prescribed order the grammatical forms of (a noun, pronoun, or adjective): decline the Latin adjective “brevis”

- 3: to cause to bend or bow downward…: the clover … declines its blooms.—W. C. Bryant

- 4: [obsolete] a: avert… evasions are sought to decline the pressure of resistless arguments …—Samuel Johnson. b: avoid… sinners … despairing to decline their fate …—Thomas Ken

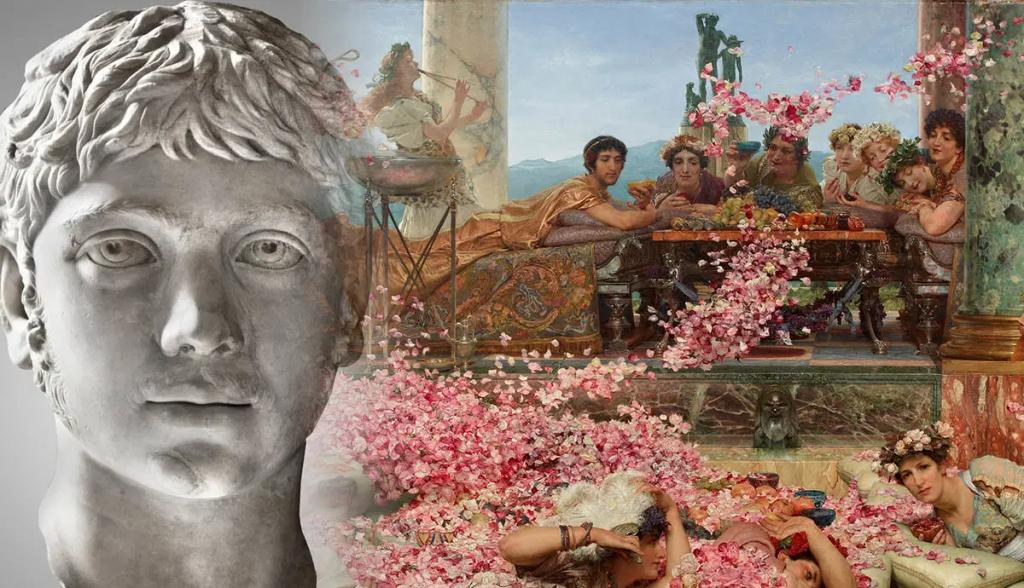

Yet all of those meanings are potentially possible. Can we refuse to join history at its invitation or take part in it as an active or passive agent? Can we evade or avoid it, either? And can we change its significance so that it becomes less significant, or even ( a question asked of queer people at the time) can we contribute to a pattern of historical fall – as queer people were said to do to the Roman Empire from Gibbon onwards? In the latter case, the association was because of the lazy linking of weakness with queer Emperor Elagabalus, and still believed in by an eccentric Italian historian in 2011.

In protesting ‘married love’ to Alice, Gertrude was most likely placing them both in the forefront of historicised discourses about the role of queer people, but also showing that all histories (even the history of a romantic love match) could and should be in control not only of its future but also the interpretation of the past to be chosen – the one that evaluated the import of Nelly and Lilly, and also (but unspoken because Stein ‘declined’ to acknowledge that part of her sexual history) May Bookstaver. The fact is that sometimes histories have to be rewritten at a very deep level, even in the everyday of the language we use to construct our daily lives.

When Alice eventually learned of the role of May Bookstaver (now Knoblauch) in her wife’s past, she claimed that she would refuse to type up any reference to May in Stein’s wring, Wade tells us. it is a testament to how deeply wordplay constitutes a ‘reference’ in that writing that Alice insisted that every use of the word ‘may’ in the manuscripts be changed to some other word, such as ‘can’. Here is the proof from Wade’s book (I find this sign of a control by jealousy most difficult to read about):

However there are other ways that queer history has been declined in mainstream history that may not be as consequential personally but are consequential. Usually this has involved the rubbishing of the witness of queer historical personages (and my own feeling is that still frequently happens to Gertrude Stein – witness Rachel Cooke) although sometimes the animus against them is disguised, as Cooke’s is. Thus, Gibbon on Elagabulus gives a gender-queer, if not gay, portrayal of him:

As the attention of the new emperor was diverted by the most trifling amusements, he (A.D. 219) wasted many months in his luxurious progress from Syria to Italy, passed at Nicomedia his first winter after his victory, and deferred till the ensuing summer his triumphal entry into the capital. A faithful picture, however, which preceded his arrival, and was placed by his immediate order over the altar of Victory in the senate-house, conveyed to the Romans the just but unworthy resemblance of his person and manners. He was drawn in his sacerdotal robes of silk and gold, after the loose flowing fashion of the Medes and Phoenicians; his head was covered with a lofty tiara, his numerous collars and bracelets were adorned with gems of an inestimable value. His eyebrows were tinged with black, and his cheeks painted with an artificial red and white. The grave senators confessed with a sigh, that, after having long experienced the stern tyranny of their own countrymen, Rome was at length humbled beneath the effeminate luxury of Oriental despotism.

But history is declined in other ways too, as Wade shows – particularly in the understanding and appreciation of the true agency of people named as passive – in a relationship – whether in national or domestic politics. Wade makes it clear that if Stein was an original collector and model for the art of Picasso, she could not claim as Alice could, to have collaborated with Picasso on art works – for instance in crafting the upholstery of the women’s homes with art designed jointly with Picasso and as its primary maker:

But queer life is also sometimes historically toned down. One of my favourite bits of evidence concerns the outrageous camp life of Sir Francis Rose and the likelihood that Stein shared it with him. when the would-be biographer Katz was making his notes of interviews with Toklas after Stein’s death, Toklas reports her worry about how interviews with Francis might go and the effect of his revelations on Stein’s literary reputation among the prudish reading bourgeoisie. I don’t think that this is, as Wade supposes, because she thought Rose would lie, though exaggeration in recall of history may have been part of his camp, but because queer people are trained to subdue themselves to fit an acceptable pattern more than are eccentric but homonormative peers, as Wade reports in the case of the queer American artist, Demuth. [9]

Rose was a privileged being and no doubt an exaggerator, but Alice was a reserved one and his ’embellishments’ may be more true than her cut-backs, or declining of the history of Paris subcultural life that was cut from most accounts – as reference even to the fact of queer sexualities often was for good and bad reasons.

Francesca Wade (2025: 307) Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife London, Faber.

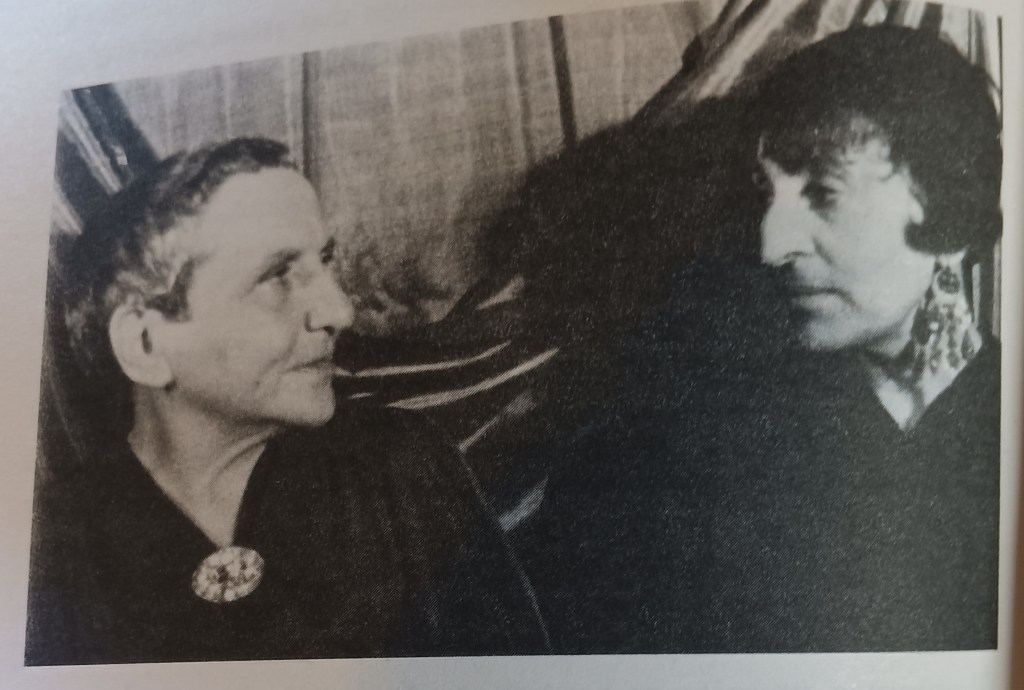

Alice preferred to seem the mousy little lady, but we have seen that Francis Rose did not see her thus but rather as an agent in getting things done and pointing out exceptional melons. I love the final photograph of the book, wherein if Stein is the more imposing physically, Toklas has the larger shadow, leaning into and possibly behind the looking-glass.

Francesca Wade (2025: 296) Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife London, Faber.

But Stein too chose means to represent herself in the literature of the ‘double’, as an amalgam of different selves crossing many boundaries, not least male and female, depending on context – but often in order to make context apparent as a binding and framing ideology. In Stein’s writing, the whole set of the old conventional structures that contributed to both writing and fabulation were up for grabs, such tbat effects could not be predicted even from the remant of notions in fabulation of plot, character and setting. Those latter effects are discernible in Joyce and Woolf, which depend on traditional expectations. In Stein too both the sentences and paragraphs are up for radical reconfiguration. Objects become subjects, possessive become possessed, and syntax does not sometimes even admit of even the shadow of what would become known as Chomskian generative grammar.

And the splittest of all characters was the narrator, to say nothing of Roses and Willys. The fabulous photographic portrait below, in the style we might say of some of Man Ray, tells us a lot. Stein looks neither to the front nor the side and definitely not to past and future lest she be mistaken for the conventional symbol of progressive time, Janus.

Stein truly wondered,’Can I decline history’ and make all new and fresh and accommodating for ‘difference ‘. We disrespect her in the queer community at our peril.

With all my love 💓

Steven xxxxx

________________________________________

[1] Francesca Wade (2025: 296) Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife London, Faber.

[2] Kathryn Hughes (2025) ‘Gertrude Stein: an Afterlife by Francesca Wade – how a literary legend was made’ in The Guardian (Mon 26 May 2025 09.00 BST) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2025/may/26/gertrude-stein-an-afterlife-by-francesca-wade-how-a-literary-legend-was-made

[3] Rachel Cooke (2025) ‘Don’t waste your time with Gertrude Stein’ [What a title! – SDB] in The Observer (Tuesday 13 May 2025) available at: https://observer.co.uk/culture/books/article/dont-waste-your-time-with-gertrude-stein

[4] See Francesca Wade op.cit: 93ff.

[5] cited ibid: 197

[6] See ibid: 372ff.

[7] See ibid: 359ff.

[8] ibid: 296

[9] ibid: 239

One thought on ““Can you decline history”(! Or ?) This blog digs into the deep soil out of which a new biography of Gertrude Stein grows: Francesca Wade (2025) ‘Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife’.”