‘The Secret Seven’ fail to catch up on ‘The Little Prince’.

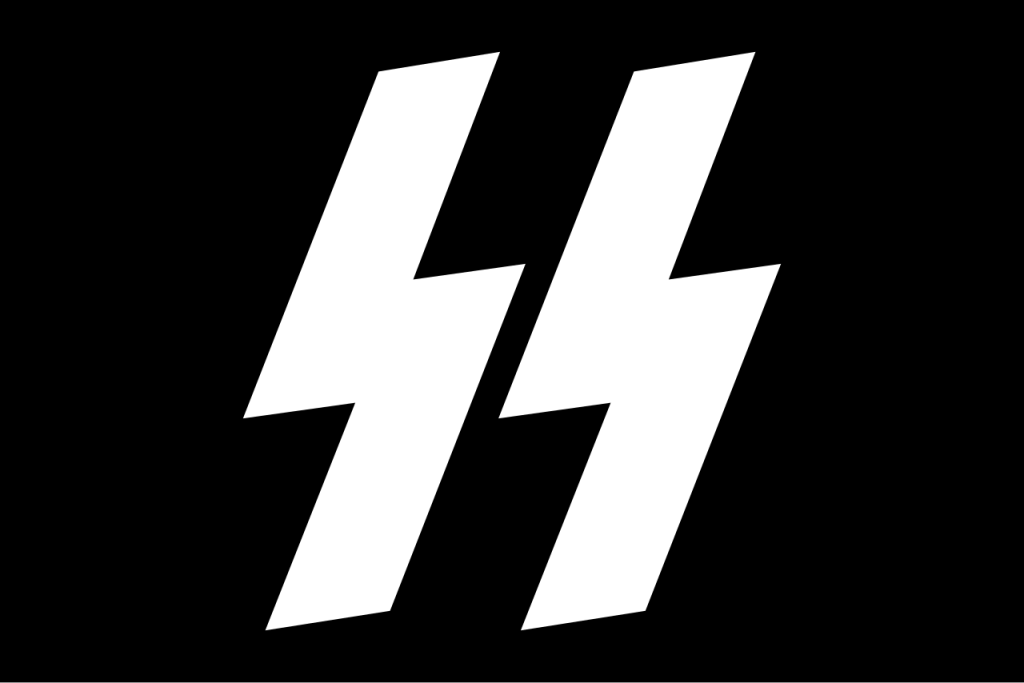

When I was in primary school, Enid Blyton ruled the world of children’s fiction, yet apart from having a kind of loving fascination for The Island of Adventure (because I liked island books), I had not even a pretend interest in The Famous Five or The Secret Seven though these were the stories other kids spoke about. I could not identify with these parties of children with alliterated self brands (the Secret Seven even called themselves SS in their ‘coded’ notes to each other). I never quite believed even then that they did not fashion themselves on the Nazi SS, the Schutzstaffel. Remember them as defined in Wikipedia:

The Schutzstaffel (German: [ˈʃʊtsˌʃtafl̩] ; lit. ’Protection Squadron’; SS; also stylised with SS runes as ᛋᛋ) was a major paramilitary organisation under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, and later throughout German-occupied Europe during World War II.

The failure of identification for me probably began with the class characteristics of these obnoxious toadies. Here is a characteristic passage (from The Secret Seven Adventure).

“What’s the meeting about?” asked Colin. “I know something’s up by the look on Janet’s face. She looks as if

she’s going to burst!”

“You’ll feel like bursting when you know,” said Janet.

“Because you’re going to be rather important, seeing that you and Peter are the only ones who saw the thief we’re

going after.”

Colin and George looked blank. They didn’t know what Janet was talking about, of course. Peter soon explained.

“You know the fellow that Colin saw yesterday, climbing over the wall that runs round Milton Manor?” said Peter. “The one I saw hiding in the bush—and then he went and climbed up into the very tree Colin was hiding in? Well, it said on the wireless last night that a thief had got into Lady Lucy Thomas’s bedroom and taken her magnificent pearl necklace.”

“Gracious!” said Pam with a squeal. “And that was the man you and Colin saw!”

“Yes,” said Peter. “It must have been. And now the thing is—what do we do about it? This is an adventure—if only we can see how to set about things—if we can find that man—and if only we could find the necklace too — that would be a fine feather in the cap of the Secret Seven.”

There was a short silence. Everyone was thinking hard. “But how can we find him?” asked Barbara at last. “I mean—only you and Colin saw him, Peter—and then just for a moment.”

“And don’t forget that I only saw the top of his head and tips of his ears,” said Colin. “I’d like to know how I could possibly know anyone from those things. Anyway, I can’t go about looking at the tops of people’s heads!”

Janet laughed. “You’d have to carry a step-ladder about with you!” she said, and that made everyone else laugh too.

“Oughtn’t we to tell the police?” asked George.

“I think we ought,” said Peter, considering the matter carefully. “Not that we can give them any help at all, really.

Still—that’s the first thing to be done. Then maybe we could help the police, and, anyway, we could snoop round and see if we can find out anything on our own.”

“Let’s go down to the police station now,” said George. “That would be an exciting thing to do! Won’t the inspector be surprised when we march in, all seven of us!”

They left the shed and went down to the town. They trooped up the steps of the police station, much to the astonishment of the young policeman inside.

“Can we see the inspector?” asked Peter. “We’ve got some news for him—about the thief that stole Lady Lucy’s

necklace.”

The inspector had heard the clatter of so many feet and he looked out of his room. “Hallo, hallo!” he said, pleased. “The Secret Seven again! And what’s the password this time?”

Nobody told him, of course. Peter grinned.

“We just came to say we saw the thief climb over the wall of Milton Manor yesterday,” he said. “He hid in a bush first and then in a tree where Colin was hiding. But that’s about all we know!”

The inspector soon got every single detail from the Seven, and he looked very pleased. “What beats me is how the thief climbed that enormous wall!” he said. “He must be able to climb like a cat. There was no ladder used.

Well, Secret Seven, there’s nothing much you can do, I’m afraid, except keep your eyes open in case you see this man again.”

“The only thing is—Colin only saw the top of his head, and I only caught a quick glimpse of him, and he looked so very, very ordinary,” said Peter. “Still you may be sure we’ll do our best!”

Off they all went again down the steps into the street. “And now,”’ said Peter, “we’ll go to the place where Colin saw the man getting over the wall. We just might find something there—you never know!”

The diction, sentence structure, and no doubt, the pronunciation of the Secret Seven Adventure all followed received patterns of what was considered grammatical and uses abstract diction, avoiding what was called at the time the ‘restricted codes’ of working-class speech which Basil Bernstein felt to be antipathetic to structured learning. It took the great Harold Rosen to critique this view. After all, Bernstein left the working classes responsible for their own lack of progression and imagined education had to rescue the working classes from their own inherited speech patterns via the adoption of embourgeoised language forms, identified as parallel with the only pathway to effective learning. This was anathema to Rosen. To me, the Secret Seven stories themselves matched the values of a society hard to identify with for a working-class kid.

The Secret Seven Adventure pitched the children of the SS on the automatic side of the police and in defence of these who built huge walls around outrageously huge estates, like Milton Manor, in order to save the jewels of Lady Lucy Thomas from people with no respect for walls – or the regulation of class differences they embodied. They run to the police with the evidence they have accidentally accrued, whilst carefully ensuring they explain its inadequacy.

When I first came across The Little Prince, I knew nothing about its controversial author, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, even of his aristocratic origins and self-reinvention. He certainly was not a working class warrior, and he chose to make his hero a ‘prince’, but a little one, in charge of a realm with a population of one: himself.

This alienated character, however, embraces this alienation partly to escape the messy world of perverted adult values. Take the book’s opening:

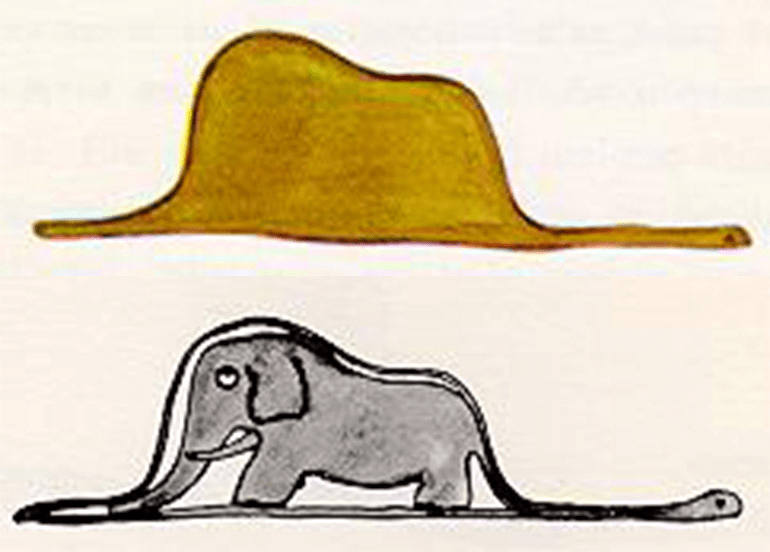

Once when I was six years old I saw a magnificent picture in a book, called True Stories from Nature, about the primeval forest. It was a picture of a boa constrictor in the act of swallowing an animal. Here is a copy of the drawing. (see below)

In the book it said: “Boa constrictors swallow their prey whole, without chewing it. After that they are not able to move, and they sleep through the six months that they need for digestion.” I pondered deeply, then, over the adventures of the jungle. And after some work with a coloured pencil I succeeded in making my first drawing. My Drawing Number One. It looked like this:

I showed my masterpiece to the grown-ups, and asked them whether the drawing frightened them. But they answered: “Frighten? Why should any one be frightened by a hat?” My drawing was not a picture of a hat. It was a picture of a boa constrictor digesting an elephant. But since the grown-ups were not able to understand it, I made another drawing: I drew the inside of the boa constrictor, so that the grown-ups could see it clearly. They always need to have things explained.

Adults weren’t in this fiction ‘authority’ to be respected and to be helped by your limited capacity to adventure and play. They were not people you allowed to patronise you. Young as you were your little authority was still a better authority. Adults were people who had taught themselves to value very little, even the duty to protect what, though beautiful, is vulnerable to the airless atmospheres they create.

I for one wanted to identify a rose I loved and hold it dear away from their mockery. So my book choice from childhood is The Little Prince.

Bye for now.

With love

Steven xxxxx