Dis/Placed: meanings in the art of Anselm Keifer metamorphose in association with the variant contexts contingent on the ‘placement’ in space and time

This blog post is a sequel to one on Part One of the Anselm Kiefer exhibition in Amsterdam at this link.

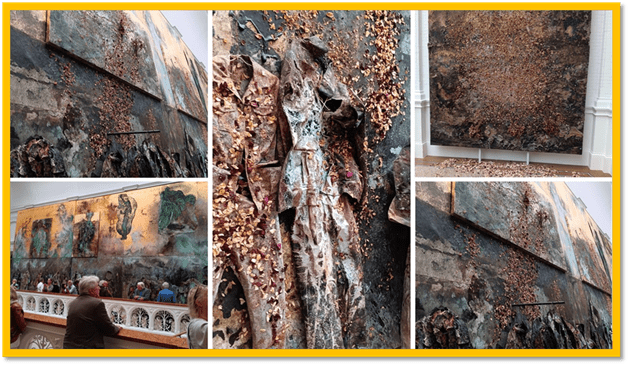

Just a glance at the new work at the top of a grand staircase in Stedelijk Museum Sag mir wo die Blumen sind (Where Have All the Flowers Gone) shows we are in different territory in Part 2 of the recent Amsterdam Exhibition of Anselm Kiefer. This work is new but continues a tradition, using some parts of and versions from the Fallen Angels works exhibited in Florence in 2024, of which more later. The photograph from the Stedelijk shows the work rather over lit and optically diminished , thus doing no justice to its effect of grandeur seen in the flesh. There is a jolt here to anyone expecting merely a continuation of the commentary of one artist an anther, namely Van Gogh and not just because the Stedelijk needs to show off its already considerable holdings of Kiefer’s work. Here the themes that transition between Van Gogh and Kiefer are absorbed into Kiefer’s world entirely. But part of the difference is determined by the fact that when work by this artist transits between spaces over time (even the small versions of these represented by the concourse between two contingent buildings, it changes character, sense and meaning. This is what my blog is about today.

In my last blog on Kiefer (at this link) I exampled this piece in Part 1of the Anselm Kiefer exhibition:

About the piece I said:

I don’t want to examine my own feelings about this artwork which I find exceedingly moving. I have tried reading the texts on that sunflower motif only to find a plethora of contexts other than merely Van Gogh that create its repertoire of meanings.

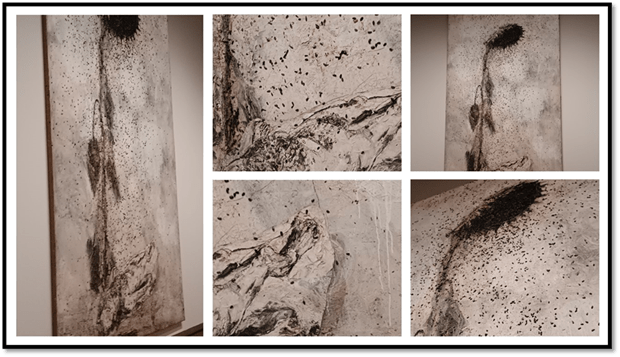

But this issue of how change of context changes the meaning, feeling and prompts to action of any piece of art has continued to trouble me. It will then be the theme of this blog. To follow that theme I have defined context in terms of any aspect of the dimensions of time and space, including changes of specific social and cultural ideas that comes with the work of art – the ‘con’ (that which surrounds something or is absorbed WITH it) to its ‘text’. I need to start by remembering again those sunflowers from Part 1, especially Sol Invictus:

Let’s take a simple instance of temporal and spatial determinants of meaning to try and explain what I mean, in part at least, by contextual interpretation In Part 1 the two pieces were interpreted by Jonathan Jones solely in relation to the context of the sunflower motif used so widely by Van Gogh and which the latter turned to certain nuanced meanings. He compared this usage with Kiefer’s to the latter’s disadvantage, as if the only way one could compare vastly different artists was by some unspoken yardstick of absolute value. But it is not so – that sunflowers change meaning by context is an unremarkable truth and more so when used as icons in graphic art. For Kiefer, the ‘seed shed by a sunflower only adds to atmospheric pollution and the effects of harmful nuclear radiation, harnessed as a means towards death by humanity. The self-portrait on which the seed falls is not only a naked but a wasted and wasting body, its genitals even shrivelled into the bush of hair that ought to surround it.

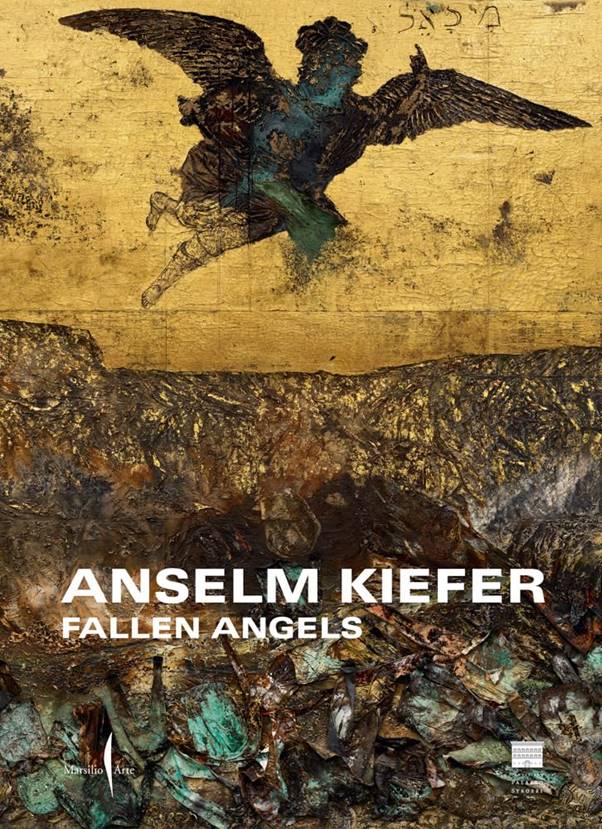

And this raises another issue. Jones writes as if Kiefer’s only intention is to compare himself with Van Gogh in relation to this motif, an intention prompted by this exhibition in the Van Gogh exhibition. However, this is not so, and the Sol Invictus was not made specifically for Part 1 of the exhibition. I learned this when I bought myself another book at the shop in Part 2, in the Stedelijk Museum. It was a book about an exhibition in another time and place, 2024 in the Renaissance Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, in which ties between Neoplatonism, medieval alchemy and the Occidental artistic Renaissance were knotted, with no references in its explanatory apparatus to the latter-day use of sunflowers by Van Gogh.

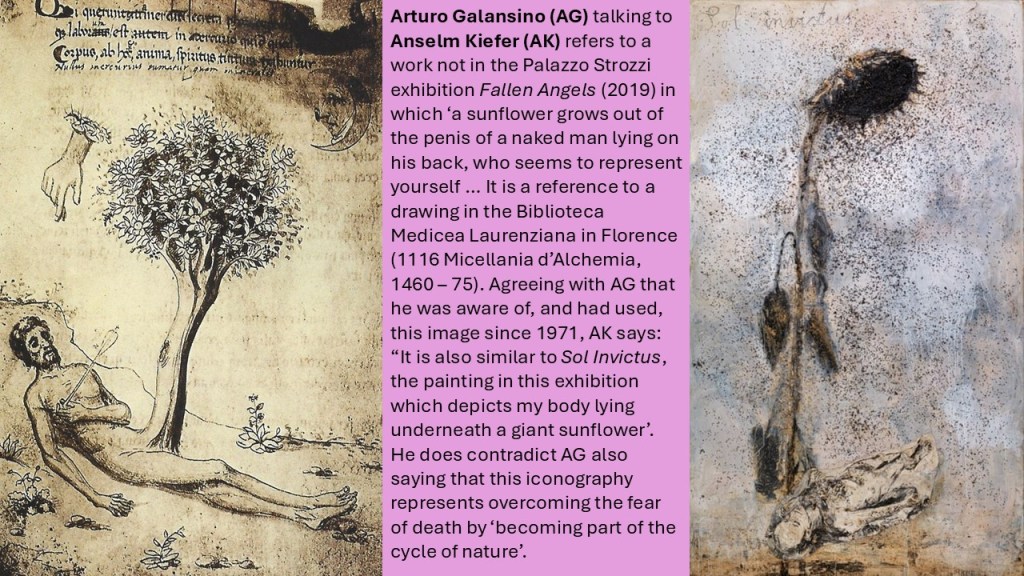

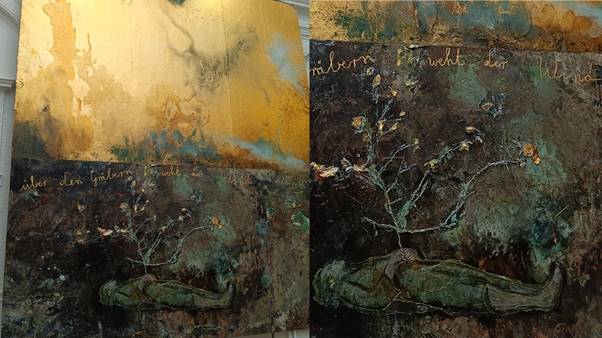

Sol Invictus was in this exhibition and the catalogue emphasises most the iconographic uses of the sunflower in medieval alchemy down to Robert Fludd. The context for Sol Invictus was less Van Gogh than an anonymous print in which a man lies on the ground like Kieffer’s self-portrait so accepting of his metamorphosis into nature, and even supernature as correspondent with the sun, as he watches his penis grow into a tree bearing sunflowers.

In conversation with Arturo Galansino (AG) at his studios in Croissy, Kiefer (AK) refers to a work that was not in the Palazzo Strozzi exhibition Fallen Angels (2024) but in which ‘a sunflower grows out of the penis of a naked man lying on his back, who seems to represent yourself … It is a reference to a drawing in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence (1116 Micellania d’Alchemia, 1460 – 75). Agreeing with AG that he was aware of, and had used, this image since 1971, AK says: “It is also similar to Sol Invictus, the painting in this exhibition which depicts my body lying underneath a giant sunflower’. He does contradict AG also saying that this iconography represents overcoming the fear of death by ‘becoming part of the cycle of nature’.[1] There is not a single reference to Van Gogh as a painter of sunflowers in Fallen Angels. The context of Sol Invictus showing in the Palazzo Strozzi does not require such reference being rich enough in other paradigmatic contexts for the art and, in this case, it should be clear to see the work does not demand it either – in this time and this space. But transport it to Amsterdam, to the exhibition room of the Van Gogh Museum alongside a range of Van Gogh sunflowers and suddenly the case is different, even though the painting is the same (or is it?).

My point here is not that we are wrong to re-contextualise the use of sunflowers in Kiefer in relation to the Dutch artist in the capital city of the Netherlands in (in part at least) the museum named after him, but that such re-contextualizations are part of the way that meanings, senses and affects yield to temporal and spatial as well as cultural-ideological contexts. The iconography of the Fallen Angels too (angels falling from the skies, alchemical negotiations – at extremes between molten lead and gold leaf material use, death and resurrection and the hubris of both body and mind – in the Palazzo Strozzi exhibition a year earlier persists in the Amsterdam exhibition but its meanings change in relation to numerous influence – the ongoing interest of the Stedelijk Museum as a major collector of Kiefer and the annexing to that its alliance to a near neighbour, resurrecting another approach to sunflowers and the complex networks in artistic influence between a nineteenth century ‘master’ and a twentieth-twenty-first century established giant figure of post-war European art. And it is not only sunflowers that can be traced to variant traditions, iconographies and spatial-temporal and socio-cultural variations of context and hence meaning, but paths, avenues, prospects and perspectives.

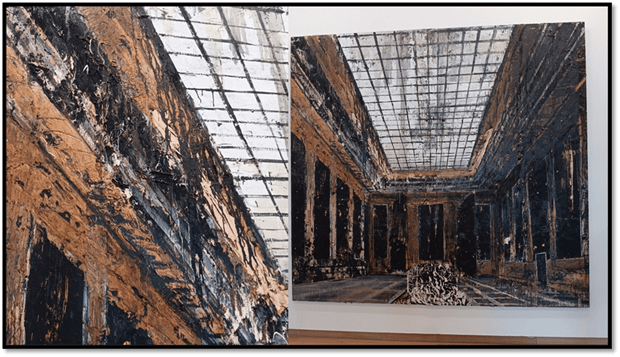

As we enter the Stedelijk Museum, we are urged to look at two paintings first from its own collection that are claimed to be germinal to the ideas in the exhibition and in the artist’s entire work: Resurrexit (1973) and Innenraum (1981). I include them here but have no idea why they are so called out, despite the presence in them of many common motifs – attics representing the brain / mind, serpents representing worldly knowledge and do on but Resurrexit os not a painting that grips me as do others, in my present state of appreciation, at least. All I see is that it speaks of the attempt to separate mind from vegetable and animal nature, pretends that to go upward is always a slog up a triangular hierarchy than a slither over uneven ground and that mind dries out living wood to make walls and barriers

Innenraum is more intriguing to me but not in any way I can articulate – perhaps I am still stuck with why Kiefer so needs to query Speer’s Nazi architecture.

Nothing in these pictures prepared me for climbing the staircase to see Sag mir wo die Blumen sind, the exhibition catalogue’s introductory explanation of which I excerpt below in a photograph of the appropriate page. But it is there partly in irony, for among the many dried versions of natural things that ‘flutter’ from those works (and other for I cannot know from whence it derived being found kicked or blown into the centre of a gallery floor (like ‘the answer, my friend‘ that is ‘blowing in the wind‘, its origin untraceable and other paintings, was a dry and rather damaged leaf, photographed lying on the page. The commentary below could fit some of the thoughts that accompany the finding and keeping of this leaf: It might ‘symbolize the connection of heaven and earth and the cycle of life and death’ but I find such readings too conventional and culturally generalised to matter much to me. It does matter though to feel the need in Kiefer the demands of what people generally call high and low culture, and the people who suffer that division of human significance on either side as its objectified examples(often now dead), rather than subjectively continuing beings.

These persons include, scattered as if blown by the winds around the walls and divorced from the usual culturally validated categories and heavily hierarchically sequenced evaluations of them – from Heraclitus to the people in Charcot’s clinics forced to be paraded in front of his students, and fashionable Paris, as test-cases of human cognitive and affective failure. The ‘connection of heaven and earth and the cycle of life and death’ is too glib a formulation of the disorder that Kiefer creates in these connections – even in the ranking of materials which wants to break down the cultural evaluations which place gold before lead, the idealised thinker before the psychosomatic bearer of ideas, whose role is not to manipulate them but suffer their agency. even those that seek to evaluate the relative worth of being what one is – whether the imagined supernatural, the human, animal, tame or wild, pure or mixed, civilised or feral, gold or lead, that which does not rot (not obviously) and that which does, and the damaged and the ‘whole’.

Figure full formed, emergent of fallen into lees recognisable form fill the mix – sometimes with faces recognizable from art – philosophers, saints or the newly created and unclassified.

One form in which life distinctions are symbolised is through clothes and many hang from the walls around the staircase gallery ot are stuck on it / fixed.

Are we meant to want to try them on – to dwell in them – or merely absorb them as part of a whole aesthetic experience as some element of venerated art? Likewise the dried flora on the floors that falls and scatters continually from their insecure places on the walls – even the leaf I showed you now pressed in my Anselm Kiefer books. Are these art? Or are they valued rather in their loss and scattering like seed is sometimes.

Things are falling and failing continually that we consider pure – angels from a golden empyrean, leaves from a place where once they were secure, the petals and seeds of flowers – even sunflowers. Does what is fallen matter less than that which holds its position stable? If we think so, why. Hence the import of Heraclitus: ‘Everything flows’. It ‘blows in the wind’. But is things fall maybe they rise in value too, or hover – like lead in alchemy metamorphosing to higher value. Our eyes saccade up and down as well as left and right on the walls dramatising the falls, and the rises and lateral transitions of things. And growth itself is a kind of rise, as in Resurrexit I suppose, upwards.

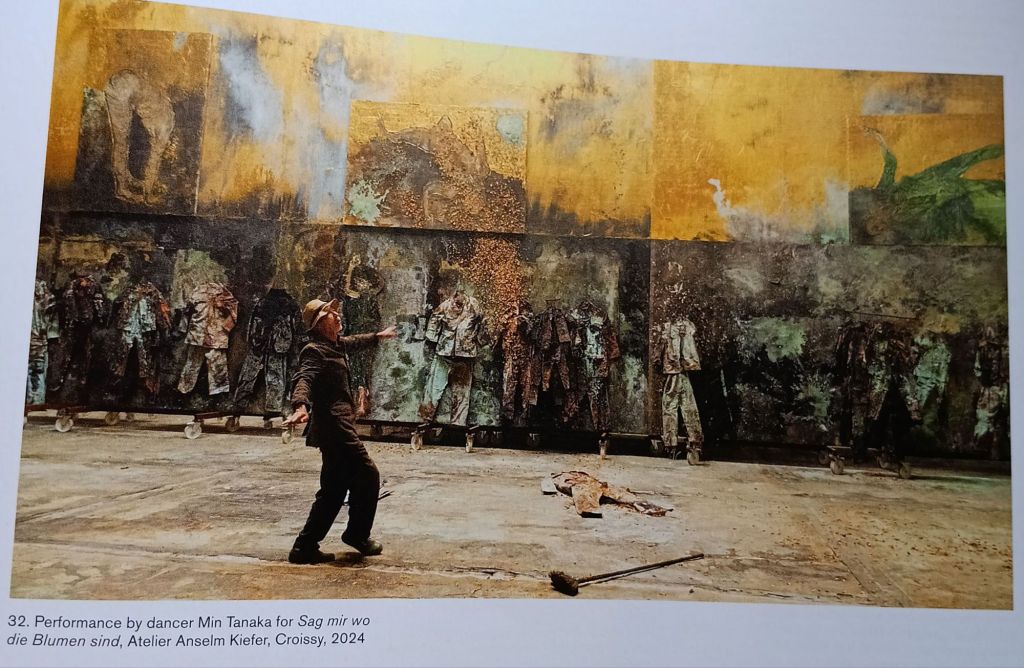

Ar the end of the whole exhibition you can see a brilliant film of a dance performance with this piece, in location in Croissy before it came to Amsterdam.

Above Mun Tanaka dances with the artwork in Croissy: still from the 2024 film from ibid:185. Below: my photographs taken as watched the film.

Tanaka literally dances with the art, not only sweeping across it, but raking down elements from it to examine or use. In the still immediately above on the left he dances formally with the uniform of a young man before throwing down the garment discarded like the brush near he he uses elsewhere as a tool (as a brush) ot as a prop representing a gun or staff – or whatever his danced moves needs us to imagine. The moment when the uniform falls (Pete Seeger’s song sings over the Whole) we wince with the rich narratives concealed:

Where have all the young men gone?

Long time passing

Where have all the young men gone

Long time ago?

The uniform is a war uniform. We know where many young me go, or fall -but, unlike the angels, unnoticed. Art gets noticed usually but Kiefer sometimes wonders why we venerate thongs because as convention dictates, they are stuck on walls and framed. Would a mere splash of paint get the same effect, or a single lead, or a rural dibber posing as a suspended sculpture,

The Women of the Revolution (1986)

What of other art genres like film. Kiefer’s work Rising, riding, falling down (2024) is a wonderful example of a complex message about the nature of materials and their transformative energy – both fake or genuine in effect – on its subject matter, but reduced here to a lot of plastic material featuring a lot of content images from Kiefer’s work, not usually as printed film on acetate but stuck uncertainly on together with metals, ash, plaster, hair, feathers and dry plants. It is an amazing work.

But perhaps we have stayed too long in Stedelijk and are in danger of becoming Jonathan Jones seeing all this as a continuum of the poor reproduction of Van Gogh motifs, as we return to the central room in which wheatfields and whole armies of real scythes on the wall come together and where Van Gogh crows become distant sights of fallen angels. The danger of being Jones does not last long. These pieces transfix me too and in different company in a new place and time begin to acquire new meanings that nod to Van Gogh but do not compete with him.

And Van Gogh’s impasto is something different from the mercilessness stuckness of materials in Kiefer.

When we change places and realise that times have changed with place, associations mean differently. I long for that place where ‘all the flowers’ and ‘the young men’ have gone, but I am left with images stuck together from dissonant materials to form meanings that never comfortably stay the same but change with my context in time and space – and theirs. For both of us these contexts are multiple but how much more so for the words and images that tend to make us see our lives anew, in joy or disturbance but probably both.

With love as ever

Steven xxxxxx

The end of my Amsterdam blogs has arrived.

[1] Arturo Galansino & Anselm Kiefer (2024: 21f.) ‘In conversation Croissy October 16 2023’ in Arturo Galansino & Ludovica Sebregondi (Eds.) Anselm Kiefer: Fallen Angels Marsilio Arte & Fondation Palazzo Strozzi

One thought on “Dis/Placed: meanings in the art metamorphose, and the variant contexts are at base space and time”