Anselm Kiefer said in a lecture in Tate Britain in 2019 (abridged for the new Van Gogh exhibition in Amsterdam in 2025 as an introduction to the catalogue): ‘Van Gogh’s composition is minimalist. There is no shimmering light dissolving the material world into pointillistic touches of colour. Van Gogh builds the landscape like a bricklayer, brushstroke by brushstroke. He is not interested in the surface of things, their radiance, their appearance: in constructing he creates a new context’. It sounds so simple until he says that the context Van Gogh reminds Kiefer of , speaking specifically of Starry Night, ‘String theory – different multi-dimensional spaces arising out of each other – …’.[1]

For the blog on Part Two of this exhibition, use this link.

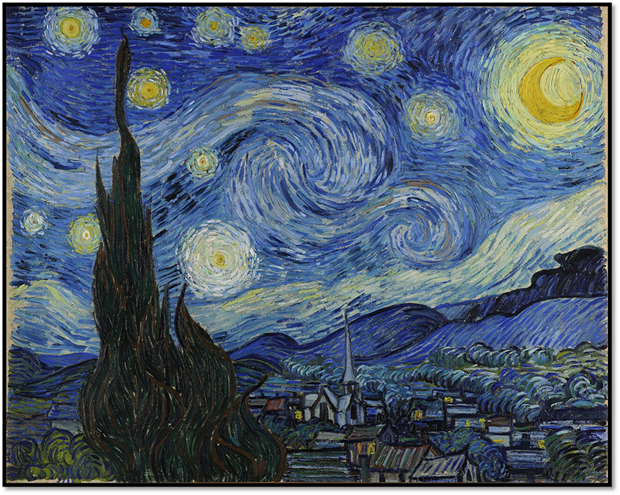

Anselm Kiefer said in a lecture in Tate Britain in 2019 (abridged for the new Van Gogh exhibition in Amsterdam in 2025 as an introduction to the catalogue): ‘Van Gogh’s composition is minimalist. There is no shimmering light dissolving the material world into pointillistic touches of colour. Van Gogh builds the landscape like a bricklayer, brushstroke by brushstroke. He is not interested in the surface of things, their radiance, their appearance: in constructing he creates a new context’. It sounds so simple until he says that the context Van Gogh reminds Kiefer of , speaking specifically of Starry Night (1889), ‘String theory – different multi-dimensional spaces arising out of each other – …’.[2] Of course, I don’t know how much knowledge of string theory Kiefer (since to call my own knowledge limited is to over-exaggerate it) intends us to know in making an analogy between it and the composition of graphic spaces in Van Gogh’s art, but I found one particular element of that definition useful to try and understand what might be meant in the New Scientist’s online definition, wherein they speak of a ‘radical assumption’ made by that theory:

string theory has to make one more radical assumption. That instead of living in a universe with three dimensions of space and one of time, we live in one with either 9, 10 or 25 dimensions of space. These extra dimensions are then curled up so tightly that we don’t notice them – much like a silken thread appears one-dimensional until you get close enough to notice its width.[3]

The sense that there are many coexistent contexts possible in time and space, each measured by any number of dimensions, certainly helps us to see Van Gogh’s paintings differently, perhaps even each time we see them. So inadequate are our own three dimensions, Kiefer sometimes evokes the learning imagined in magical systems such as religions, folklore, and even alchemy – not unlike Carl Jung in that respect. For instance when speaking of Starry Night (1889) he the stuff of Romantic fable and poetry to invoke what Friedrich Hölderlin calls the ‘silence of the shadow world’.

Constructed from ‘brushstrokes that form spirals’, the otherness of space-time in this world is such that it queers everything we see, which form their own spirals and even internal illumination, prompting the emergence of a ‘strange dragon, which recalls Saint john’s Book of Revelations’. A church spire looks like ‘a probe’ that ‘seems to tap into’ the cosmos, ‘to explore the monstrous billowing plasma’. The effect Kiefer goes on to say is to threaten the human world below the ‘all-devouring lights of the firmament’ with a fate that will ‘consume and extinguish them’. The markers of the normative things of human society (houses, windows, streets) appears now ‘strangely lost and disorganised’. [4] Personally I do not see that description aseither otiose nor flamboyant but nearer to capturing a sense of the piece than the dry descriptions of normative art history. Indeed, I think it was seeing this painting a long time ago that made me realise how redundant is art history to actually attempting to see what is distinct on an artist’s work (for evidence see this linked blog if you want to).

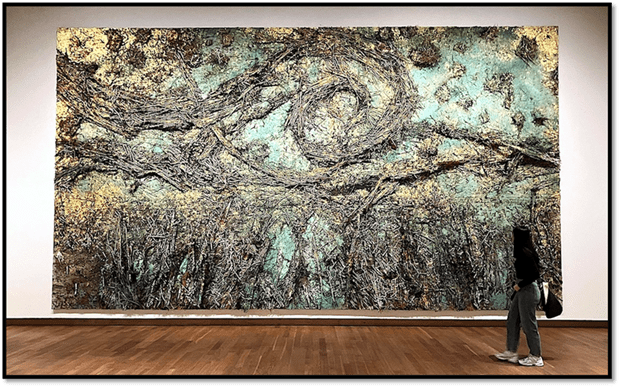

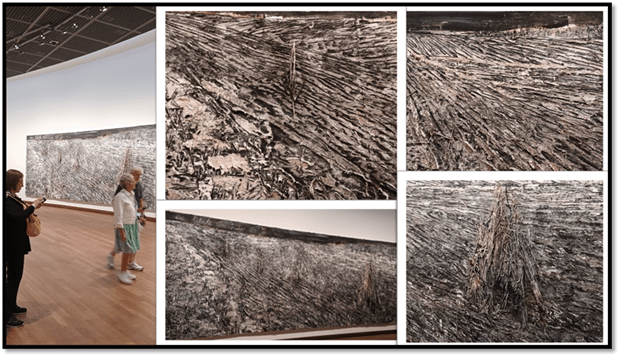

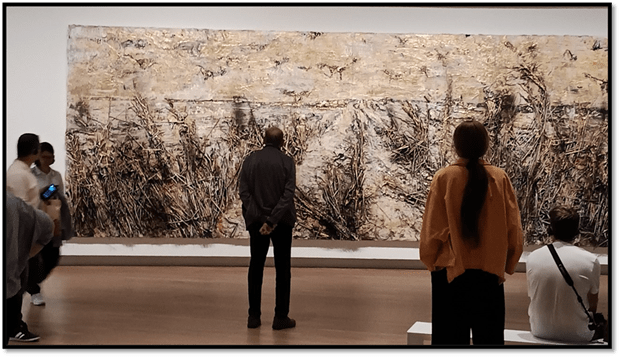

But Kiefer being a great artist constructed his own version of The Starry Night (Die sterrennacht) in 2019. – see above. In a 2 star (our of 5) review of this exhibition in The Guardian, Jonathan Jones describes this work as a ‘colossal “painting”’ that ‘recreates Van Gogh’s Starry Night in vast swirls of real straw’.[5] Jones aim here as elsewhere in his work is to find a reductive way to describe work that remains un-illuminated in the process, whilst pretending to the kind of crude accuracy so loved by art criticism when it turns to bitter comparisons in order to characterise art that is less good than it pretends to be. But the problem with Jonathan Jones as a critic is he too often uses such thin descriptions to pretend that he is representing the artwork as it is not as it seems to a careless glance, his own. In the social sciences Clifford Geertz the anthropologist showed that thin description leads to thin knowledge and that we need a description of what is before rich in consideration of analytic and contextual sources of information. He called the act of doing this thick description. And Anselm Kiefer describes Van Gogh’s paintings with that methodology in mind whereas Jonathan Jones describes neither Van Gogh nor Kiefer thus.

The relative size (470 x 840 cm) of the Kiefer ensures that our vision of it and its details are the more subject to our perspective on it, regulated by the point from which our view originates than in the Van Gogh (73.7 x 92.1 cm). If we see, as Kiefer does, a dragon in Van Gogh’s work (see above), it seems plausible to me that I see it in some perspectives of Kiefer’s version of Starry Night too (e.g. in the bottom left detail in the collage below): its wings furled. That shape or shapes metamorphose to abstract forms in other details or (to me at least) in the bottom right in the below collage, the eye and wing of a bird (a crow perhaps). Finding such meanings is is about the shifting of vision to other contexts – those of myth or the stories of ecological extinction or war of our own time. I could not find a single tutor in The Open University in the Art History MA I abandoned prepared even to try and understand that point regarding that wondrous re-vision-er, Pierre Bonnard.

Strangely enough Jonathan Jones gets really sour at Kiefer most when he blames that artist, someone Jones claimed he has ‘always seen as a creative giant’ for deserting his own modern subject-matter. Jones says this subject-matter is the Second World War (although for Kiefer that recollection – unacknowledged by Jones – is to find a pattern for the wastefulness of all wars) but which has lately found its subject in the human war on animal and vegetable nature. So sure is Jones that Kiefer has met his Götterdämmerung in confronting nature, and its master painter Van Gogh, he writes his crassest paragraph yet from my experience of his writing:

Kiefer’s best painting, however, is a grey expanse of ruined nature with a fire-fringed horizon. It belongs in a different show. One that mentions the war. Then he’s back to piling up dried vegetation in an outsized recreation of an early Van Gogh painting of a Dutch woodland, or sticking a single dead sunflower in a vitrine spilling its seeds on to an open book. There is darkness in Van Gogh, and madness and isolation, yet it’s tempered by his humble vocation of looking at the world. Kiefer uses massive scale instead of the small pictures Vincent painted, heaps of dead stuff instead of trusting in paint, sensation instead of substance. It’s all sound and fury. On the next floor you find it signifies nothing. [6]

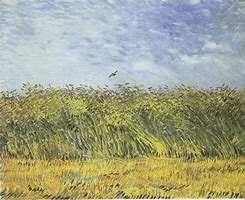

Kiefer has no such patronising view of Van Gogh. To him Van Gogh is not a nature painter and Romantic, though Van Gogh thought he was that too, but a man who through dint of hard work is an existential statement that reality is more complex than shallow vision and thin description know and must be known through bold experimentation, not mere ‘talent’ (something that Kiefer feels neither he nor Van Gogh had by nature) in the same manner as Nietzsche performed philosophical thinking. In Kiefer’s Starry Night the only real similarity is in the matter of composition, although much more expanded into the third dimension (of thick layering) than Van Gogh, and hence requiring more transitory materials than paint – dead straw, leaves. This is not to signify ‘nothing’ but to make large claims about the sources of the present Apocalyptic moment in the fields of human war and war against nature. Yet it can be described compositionally as Kiefer describes Van Gogh at his most useful reduction of the artist’s methodology in Wheatfield with Partridge (1887):

A simple three-layer composition: sky, wheat blowing in the wind, and at the bottom, a narrow strip where the wheat has already been cut. A lone bird in the sky hovers near the centre.[7]

In Kiefer’s Starry Night there is a layer but the dead cut grass becomes the only medium possible to represent life – this is what gives it apocalyptic context and thickness of description. Part of that comparison of layers relates to the use of metals to create layering and colour contrasts. Kiefer’s Starry Night uses extensive gold-leaf at the top left of the canvas that moulds background and foreground in the three dimensional shaping that emerges from it. I will have more to say about the use of lead and gold in the next blog in relation to the myth of fallen angels and alchemical relations. For me Kiefer’s use of gold recalls most Marx’s commentary on the metal in The Critique of Political Economy in which the value of gold rests in part on illusions of power and superior value, that contrasts with the colour of dried grass – the stuff after all of flesh if ‘all flesh is grass’ as Scripture insists (but again mire on this in the blog on Part 2 of the Anselm Keifer exhibition to come – but people need more contact with the genius of Marx so I will quote him here anyway):

Metals in general owe their great importance in the direct process of production to their use as instruments of production. Gold and silver, quite apart from their scarcity, cannot be utilised in this way because, compared with iron and even with copper (in the hardened state in which the ancients used it), they are very soft and, therefore, to a large extent lack the quality on which the use:value of metals in general depends. Just as the precious metals are useless in the direct process of production, so they appear to be unnecessary as means of subsistence, i.e., as articles of consumption. Any quantity of them can thus be placed at will within the social process of circulation without impairing production and consumption as such. Their individual use-value does not conflict with their economic function. Gold and silver, on the other hand, are not only negatively superfluous i.e., dispensable objects, but their aesthetic qualities make them the natural material for pomp, ornament, glamour, the requirements of festive occasions, in short, the positive expression of supra abundance and wealth. They appear, so to speak, as solidified light raised from a subterranean world, since all the rays of light in their original composition are reflected by silver, while red alone, the colour of the highest potency, is reflected by gold. Sense of colour, moreover, is the most popular form of aesthetic perception in general. The etymological connection between the names of precious metals and references to colour in various Indo-European languages has been demonstrated by Jakob Grimm (see his History of the German Language).

Finally the fact that it is possible to transform gold and silver from coin into bullion, from bullion into articles of luxury and vice versa, the advantage they have over other commodities of not being confined to the particular useful form they have once been given makes them the natural material for money, which must constantly change from one form into another.

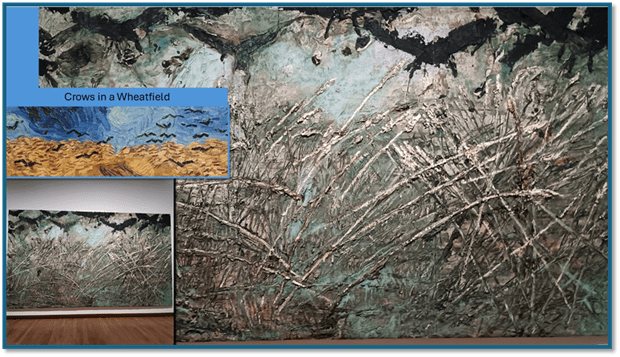

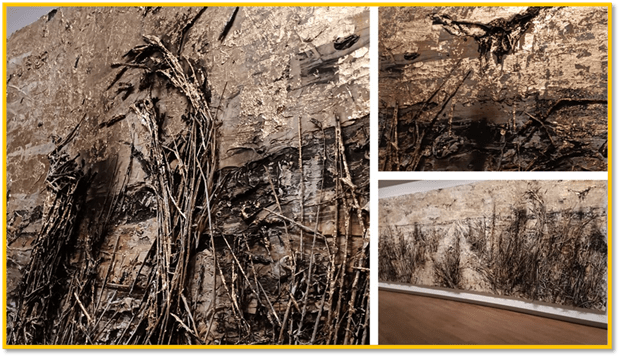

How much more might this be an issue in Kiefer’s version of Van Gogh’s Crows in a Wheatfield (1890: 50.5 x 103 cm) which is 330 x 570 cm in size, in which Van Gogh’s golden-coloured wheat takes the texture and look of lead in Kiefer’s painted dead straw. Kiefer tells is that he learned from Van Gogh that you need not think of Van Gogh as insisting on the real presence of a wheatfield in front of these paintings, but its rendering as a kind of composition of abstracted forms, especially in the birds, which are often little more than two chevrons of black paint. For Kiefer, Van Gogh is building a world that isa world of ‘struggle’:

The painting is almost abstract. What remains is the memory of something specific that has almost completely disappeared. So what of his version (see the collage below). His birds are rather less abstract than Van Gogh’s but are also less obviously feathered beings – the black daubs recall bats as much as crows, or even distant winged infernal angels. They seem even capable of being war-planes depositing bombs on earth that ought to sustain life not death. Some black daubs seem like falling bombs in the strange green translucence like that of rot or oxidising metal through which they seem to fall..

What has disappeared in both works is the ‘self-secluding earth’ beneath the vision Van Gogh imposes on it and it is to this to which modern warring humanity has lost its relationship. Even Van Gogh can only struggle to re-establish that relationship. The struggle in Kiefer is starker – the battle perhaps already lost, as the world turns into the green of oxidized copper.

To metamorphose Van Gogh’s landscapes into the field of a lost final battle does not seem so strange to me, though it was further off in the prior artist’s lifespace. Fields are full of debris transplanted from life and stuck there in thick impasto like a fly might be in amber.

Perhaps the most telling version of seeing that feeling of materials sticking in each others orbit is the wonderful Waldsteig Forest (2023) in which autumn falls as gold, like Zeus impregnating Danae (perhaps the most pernicious of the Ancient Classical stories of rape of the earth by power. It is huge (280 x 230 cm) but its layers almost make it thick, though that thickness when seen from its edge are not that of layered thing but things in a primeval chaotic but hardened soup, in which read dead leaves play a part as well as the material we call ‘gold leaf’.

This picture is not the same as but shares its metaphors with Van Gogh in various paintings of avenues. But it owes to Van Gogh that Wheatfield with Crows, among other paintings of paths and avenues into the distance, the fact that the dutch painters struggled always to find a path that does not come to a premature end and / or get blocked (sometimes as an illusion of light or perspective or the brutal reality of an intersecting wall (as at Wheatfield at Sunrise). Of the path (in lurid green) in the Crows example he says, speaking brilliantly about its reversed perspective:

The vanishing lines do not converge at the horizon. The central path does not end at the horizon. It terminates earlier, leads nowhere’. [8]

In Kiefer’s version The Crows ((2019, 280 x 760 cm) the same phenomena are reinforced by the straw forming a stumbling block to the eye throughout the central path, which seems to want to show itself as both progressive to the horizon and blocked by wall. It is a wall of gold that consumes the vision, like Fafnir the Giant’s is in The Ring Cycle is before he turns into a dragon hoarding that gold..

Jones says that ‘Kiefer can’t do small or subtle’, but that equation of subtlety with the small-scale does justice neither to these two artists nor to the process of constructing art . Jones insists that huge size is vulgar and that true art draws you to it by the readability of its apparent simple marks that stand for many things:

Van Gogh’s paintings have been hung opposite a wall of golden, encrusted, gargantuan Kiefers. Do the big 21st-century works overwhelm the poor little 19th-century ones? No. You are drawn magnetically to Vincent’s. The Van Gogh Museum doesn’t like it if you say Wheatfield with Crows is his “last” work (it’s just one of his last!) or read too much into the deathly birds streaking out of a billowing sky. But Van Gogh stood here, saw this, in this mood, and expressed his response in colours wrenched from within.

But the size and the fact of using gold leaf do not change the fact that art holds complex meanings together in one moment not because of its outward form or choice of materials alone but by the relationships it establishes with viewers. For me, both artists do that, but do so by wresting meaning out of different contexts in which meanings matter. One of the silliest moments in Jones is where he compares Vincent’s (the familiaroty is his) sunflowers with those of Kiefer. For Jones these latter are gimmicky silliness, that one hanging upside down in a museum vitrine shedding black seeds on an open book (see it below):

I don’t want to examine my own feelings about this artwork which I find exceedingly moving. I have tried reading the texts on that sunflower motif only top find a plethora of contexts other than merely Van Gogh that create its repertoire of meanings. I instanced one I saw in a seventeenth-century vanitas still life that I saw in the Rijksmuseum (see the blog at this link).

Sunflowers are an icon of the eye of man and God, of the antagonism of life to death and the nuance in that antagonism, and Van Gog’s sunflowers are read too simply – which is surely what Gauguin intended to show in his portrait of Van Gogh in the act of painting sunflowers, whilst the latter look away from the artist, almost pleading with the viewer not to do this act of interpretive simplification unintended by Van Gogh:

Simon Schama in an essay in the catalogue to this exhibition tells us even more of the iconology of the sunflower, much of it perhaps unknown To ‘Vincent’. Not only do the sunflowers of each artist clearly look at first sight as if they ‘could hardly be more different, embodying, respectively, radiance and radiation’, they speak to different contexts of discourse about the ‘sun’ – one joyous and about rejuvenation the other dark and deadly. [9] But the point of seeing them together is precisely to see nuance in each artist, that in part speaks about Van Gogh’s strange odd sunflower painting Sunflower Gone to Seed 1887, where just as in Kiefer seed is death as well falling upon sterile ground (and books can be sterile ground just as much as men can). I don’t want to argue this. Just compare for yourself.

And likewise the use of real scythes in artwork made of paint and cut grass adds to the nuance of death in the esge of Van Gogh’s reaper working in a field of living golden beauty. It os just that in Kiefer, the life has already been cut and absorbed in art and cannot pretend to live other than reminding the viewer that it is humans like them who wield such tools if harvest and death – both linked.

The use of dead organic material in Kiefer sharpens the contrasts, just as the irrefutable evidence of ecological breakdown and extinctions make the living aspects of what we wrongly call economic growth look the more deadly in terms of their effect on the holistic systems that support and contextualise human life.

Are their daubs of Van Gogh colour in the field below, perhaps a poppy, or is it blood.

And clearly Kiefer was impressed by Van Gogh as a composer of scenes, especially those related to closed or open prospects in natural scenarios and his drawing experiments on his trip in the footsteps of Van Gogh at age 18 show. He learned more by imitative drawing from Van Gogh, insisting that the scene only begins with the artist en plein air before it. This exhibition shows this drawing.

It also shows he learned much of what Van Gogh had to teach about the drawing of human figures:

Moreover, if both artists where obsessed with paths and tracks, going nowhere, they were also interested in the fact that vegetation is a means of drowning for humanity, in the grass that is their flesh and not just becaise of the mud of both World Wars in which young men died horribly drowned. The painters reflect on each othewr for me:

I will return to Anselm Kiefer for Part 2 of the exhibition soon – hopefully more fluent and articulate than I have achieved being her. Sorry for that sin if mine.

With love

Steven.

[1] Anselm Kiefer (2025: 14 & 18 respectively) ‘In the Footsteps of Van Gogh’ on Anselm Kiefer, Simon Schama, Antje von Gravenitz * Tamara Klopper Anselm Kiefer: Where Have All the Flowers Gone Amsterdam, Van Gogh & Stedelijk Museums with Ghent, Tijsbeeld Publishing, 8 – 31.

[2] Anselm Kiefer (2025: 14 & 18 respectively) ‘In the Footsteps of Van Gogh’ on Anselm Kiefer, Simon Schama, Antje von Gravenitz * Tamara Klopper Anselm Kiefer: Where Have All the Flowers Gone Amsterdam, Van Gogh & Stedelijk Museums with Ghent, Tijsbeeld Publishing, 8 – 31.

[3] What is string theory? | New Scientist https://www.newscientist.com/definition/string-theory/

[4] Ibid: 17f.

[5] Jonathan Jones (2025) ‘Anselm Kiefer review – creative giant crushed under Van Gogh’s starry might’ in The Guardian (Wed 5 Mar 2025 12.00 GMT) Available at (but not worth looking): https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2025/mar/05/anselm-kiefer-review-van-gogh-stedelijk-museum-amsterdam

[6] Ibid.

[7] Anselm Kiefer op.cit: 13

[8] ibid: 23

[9] Simon Schama (2025: 51 – 55) ‘Van Gogh and Kiefer: An Affinity of Sunflowers’ in Andelm Kiefer et. al. op.cit.46 – 65

One thought on “Anselm Kiefer sees Van Gogh in Amsterdam, and the confrontation is world-changing.”