The Van Gogh Museum: Preface to seeing Van Gogh through the eyes of Anselm Kiefer

The pictures above were by other tourists than us. This blog is an intrusion into the three-part set of blogs, in effect a fourth added to them but to preface the ones on the joint exhibition of Anselm Kiefer, both retrospective and with new works especially created for this exhibition – Sag mir wo die Blumen sind {Where Have All the Flowers Gone} held by the alliance of the Van Gogh and the Stedelijk Museums in Amsterdam. The reason why relates to some peculiarities of this visit to the wondrous Van Gogh Museum (VGM), which this time and for us, took second place to the two part exhibition of old and new work of Anselm Kiefer. Part 1 of the exhibition – the subject of the next blog is in the huge circling annex of the VGM and is based on a retrospective look on how Anselm Kiefer observed and used the art of Van Gogh – both as a model of artistic process, aesthetic achievement and subject matter, whilst Part 2 (in the Stedelijk Museum [SM]) develops the ubi sunt motif in the song sung by Pete Seeger (Songwriters: Pete Seeger, Joe Hickerson, & Bert Paige):

Where have all the flowers gone?

Long time passing

Where have all the flowers gone

Long time ago?

Where have all the flowers gone?

The girls have picked them every one

Oh, when will you ever learn?

Oh, when will you ever learn?

Where have all the young girls gone?

Long time passing

Where have all the young girls gone

Long time ago?

Where have all the young girls gone?

They've taken husbands every one

Oh, when will you ever learn?

Oh, when will you ever learn?

Where have all the young men gone?

Long time passing

Where have all the young men gone

Long time ago?

Where have all the young men gone?

They're all in uniform

Oh, when will you ever learn?

Oh, when will you ever learn?

There is a connection, of course, between the two Parts, since both are a kind of commentary on the exploitation of the young and hopeful by an aging status quo: both features flowers that pass (especially sunflowers) and lives that have passed, are passing and will be born to pass too. The structure of the exhibition ought not to have a break between parts, but we felt we had an issue here. Before going to Part 2, which would involve leaving the VGM to enter the SM across the concourse, and we wanted, perhaps needed to see the permanent collection (or that part of it showing now) before doing so. This blog is about the swift attempt to at least acquaint ourselves with VGM, and I was determined it must be not as minor a glimpse as with the Rijksmuseum the day previously. The main collection is housed across the lower ground floor of the glass atrium of VGM from the circular annex, in the older section of the museum and the art is organised roughly chronologically in ascending floors from that base. Although chronological, it is a chronology that pays service in fact to Van Gogh’s artistic development and the contexts and significance of that development.

We did not spend long enough here of the four hours in total spent between the Museums to do other than give a taste of the impression of the permanent collection, however, and I am purposely omitting any machinery related to the paintings, sometimes not even naming them. Nevertheless, it is worth starting with those Van Gogh iconic flowers that were not the subject of Anselm Kiefer’s interest, the almond blossom. I took the one below to send to our friend, Joanne, who loves this picture and has a reproduction in her hall.

Of course, I wanted to send it to her with lesser known versions of the blossom, just to prove the exquisiteness of our friends’s taste. For after all, the famous famous of those almond flowers above are merely moments of glory in a tangled (almost gnarled network) network of aged woody support, thrusting their glory to the very edges of the picture frame so that they look as if they were emerging from it in order to invite your touch, without acknowledging their source of growth from the ground from which they came.

Not so its companions:

These spring both from the natural context that is represented and the painterly creativity that both designed them and let them flower in patterns of colour. They hail Van Gogh as not only a colourist but a master of design, a view that we shall see Kiefer heavily involved in both identifying, as if mirroring his own art, and exploring in new kinds of space; a space more pertinent to art’s independence of any kind of simple mimesis.

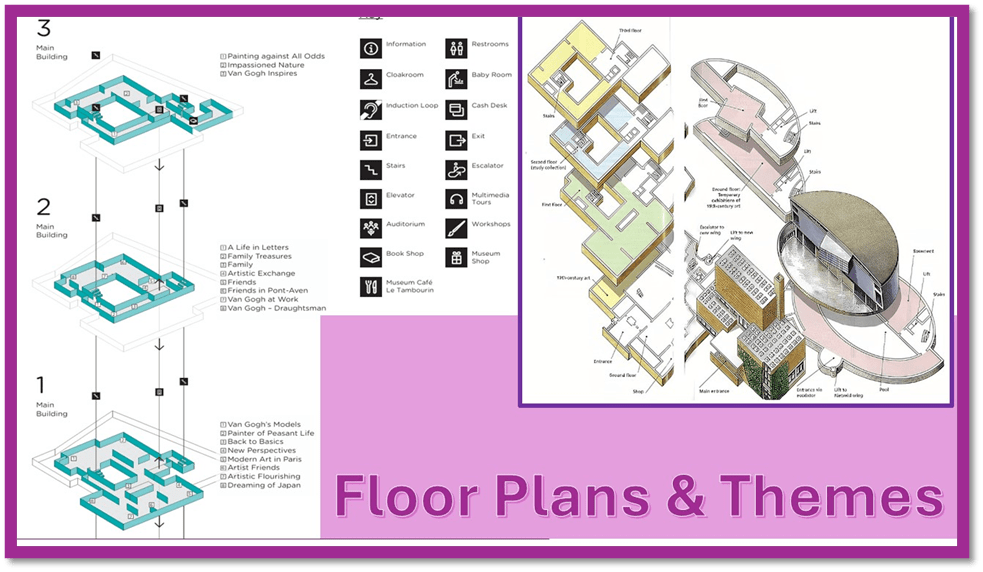

But let’s think again about the VGM. Here is the floor plan which shows how a chronological treatment is actually over-determined by a themed approach to Van Gogh’s life and art – both between the floors and in the sectioning of themes on each floor:

There you see the themes listed on the three spacious viewing floors. I will study this fully before I visit again. This time I needed to have a sense of the institutional approach and why it was so superior to that of the Rijksmuseum. My aim below is to rake a merely impressionistic sample of the tour from a few pictures we had without even standard attribution and art historical introduction.

The fact is that the problem of actually representing Van Gogh was a problem even for artists – from the very conventional portrait of him in England by an English artist, that I photographed very badly indeed:

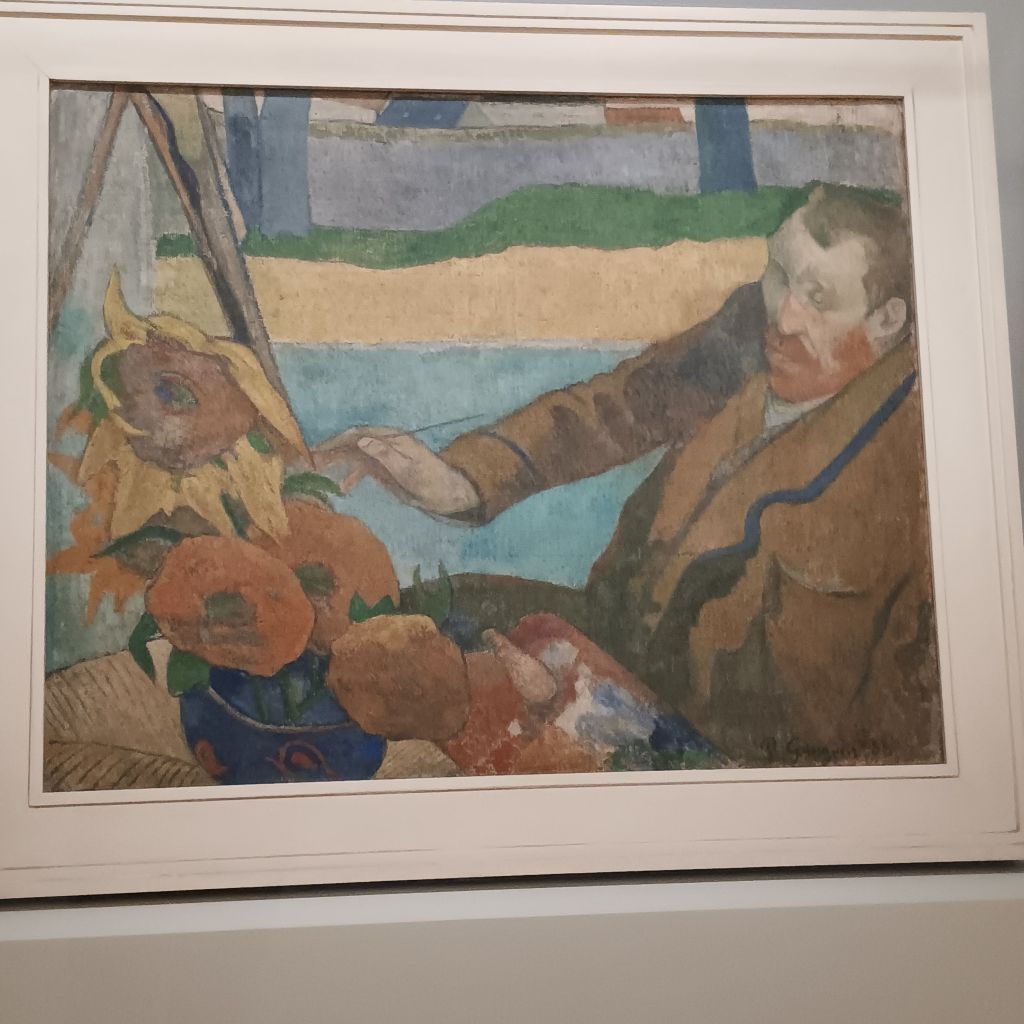

To Gauguin’s intimate view of the man painting, rather than (as above) merely holding implements of his art:

Or this sculpture attempting to capture his relation to brother Theo by an artist whose name I neglected to record (like the English artist I started with):

The issue with this museum is that every piece is there to render even more complex our grasp of the man, starting on the ground-floor with his forebears (Millet of course included) as a painter of rural life and that of its working people, in ways that made even seeing for the first time on the next floor the wonderful The Potato Eaters made it ovious that, even from the beginning Van Gogh was innovating in presenting his subjects – giving them in the process complex meanings that made mimesis a secondary aim.

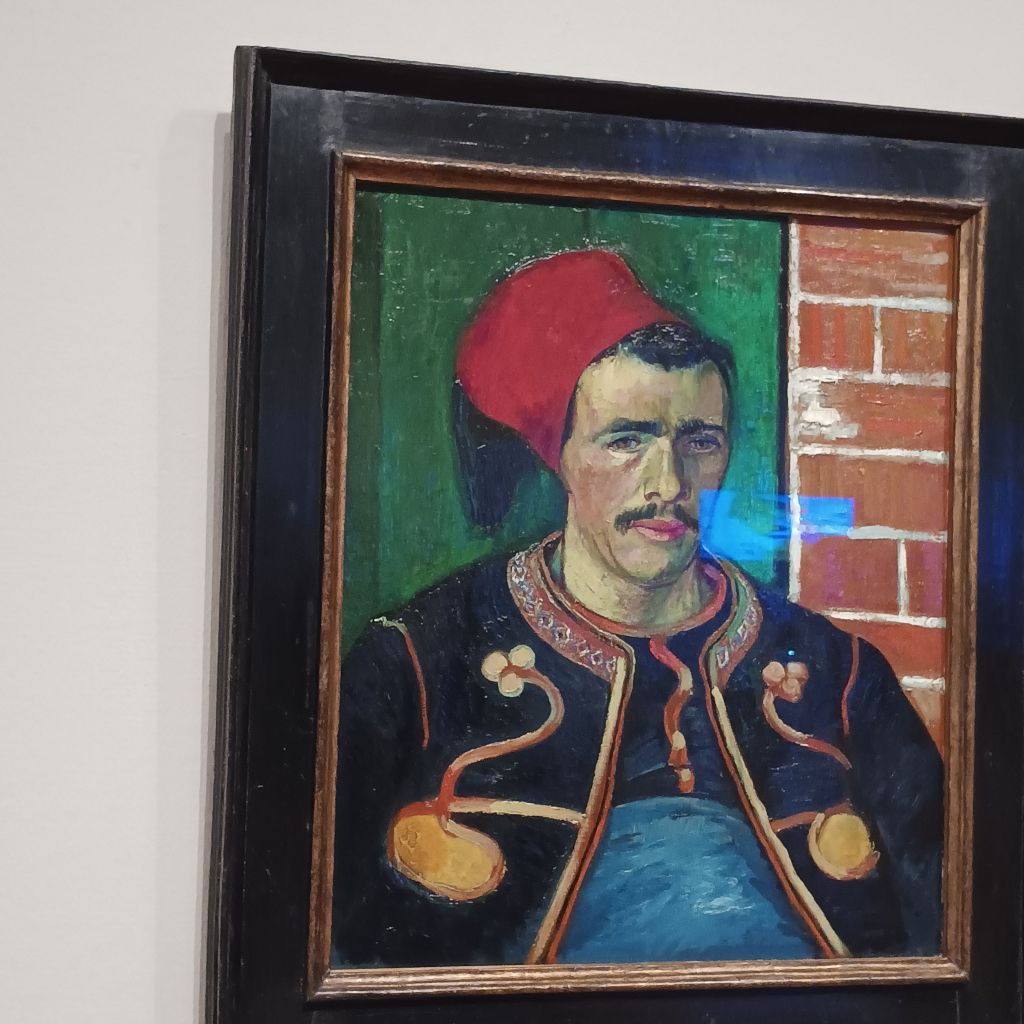

Every piece to follow – whether a raw seascape, apparently non-finito landscape , or bold portrait of a zouave, whose relationship to Van Gogh (as with that to Gauguin) seems to me to be sense with queer meaning – could not but show that each placement or complication of layered representation was intended to add rich but not very easily articulated (in words) meaning

In a sense this was because Van Gogh was a literary artist, though one who thought books themselves a complex subject to understand, even before you opened or re-opened one:

I have written too often on Van Gogh before to go further: see my earlier blogs (using the appropriate link) on his influence on Francis Bacon, on the 2024 London retrospective before I saw it, and afterwards, on seeing a set of self-portraits at The Courtauld Institute Gallery, and on reading a book on the same, after seeing a digitally projected exhibition form of him at Manchester (and before that at York), and finally a note on the 2019 Tate Modern exhibition. What amazed me was the richness of the contexts in which VGM placed their titular subject. I was expecting Gauguin but was delighted to see paintings by Emile Bernard, the first ever i have seen in the flesh. And even more, since my object here was an exhibition tracing networks of association between Van Gog and kiefer, was the richness of paintings claimed to be influenced by him. Most surprised me – especially that naming of Van Gogh as an influence on the symbolist, Odilon Redon. I was delighted (again for the first time) to see Redon paintings in the flesh, but unconvince that I ought to see Van Gogh some way in these.Redon’s nature has taken total flight from representation even in flower painting.

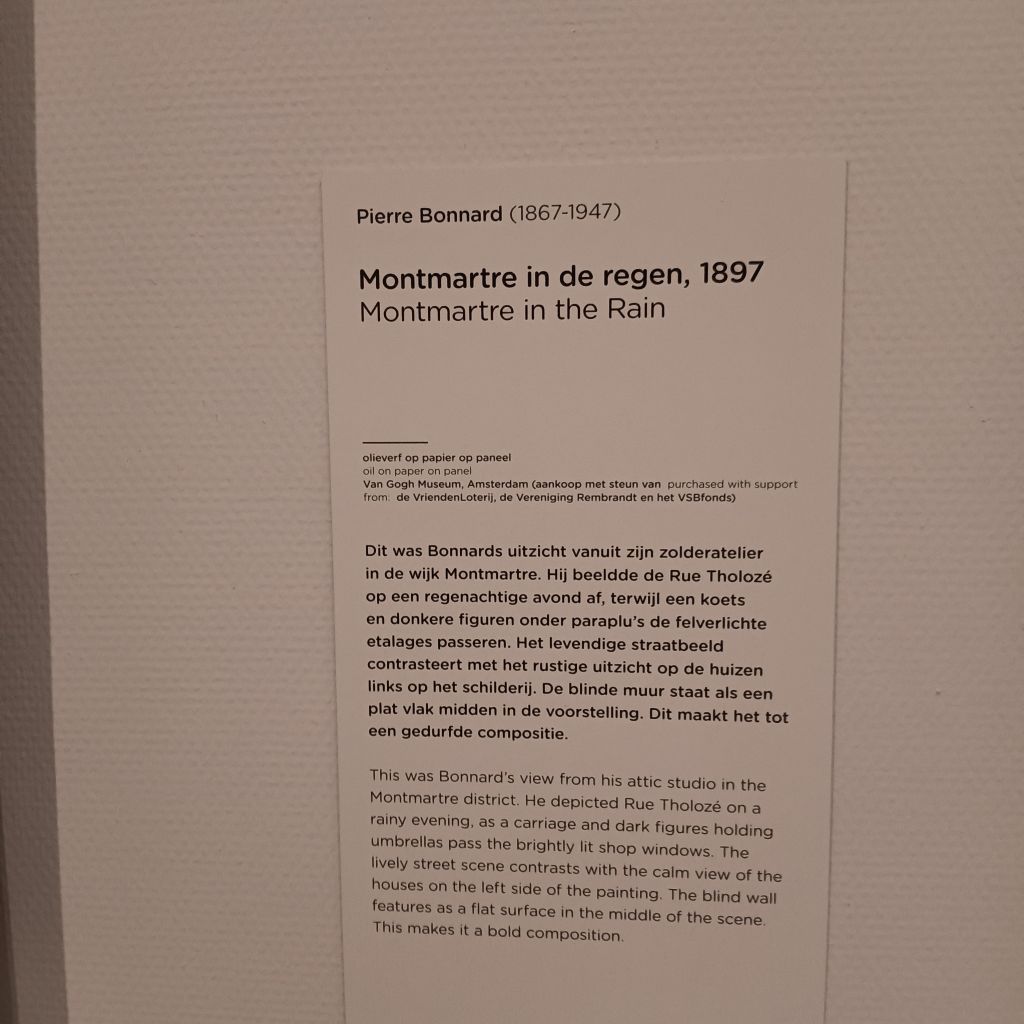

Even more surprising was the claim made about Bonnard, though one senses this great colourist knew Van Gogh and of his significance. I could have hoped that the case would have been argued, especially regarding the painting below but, as you can see below, it is not.

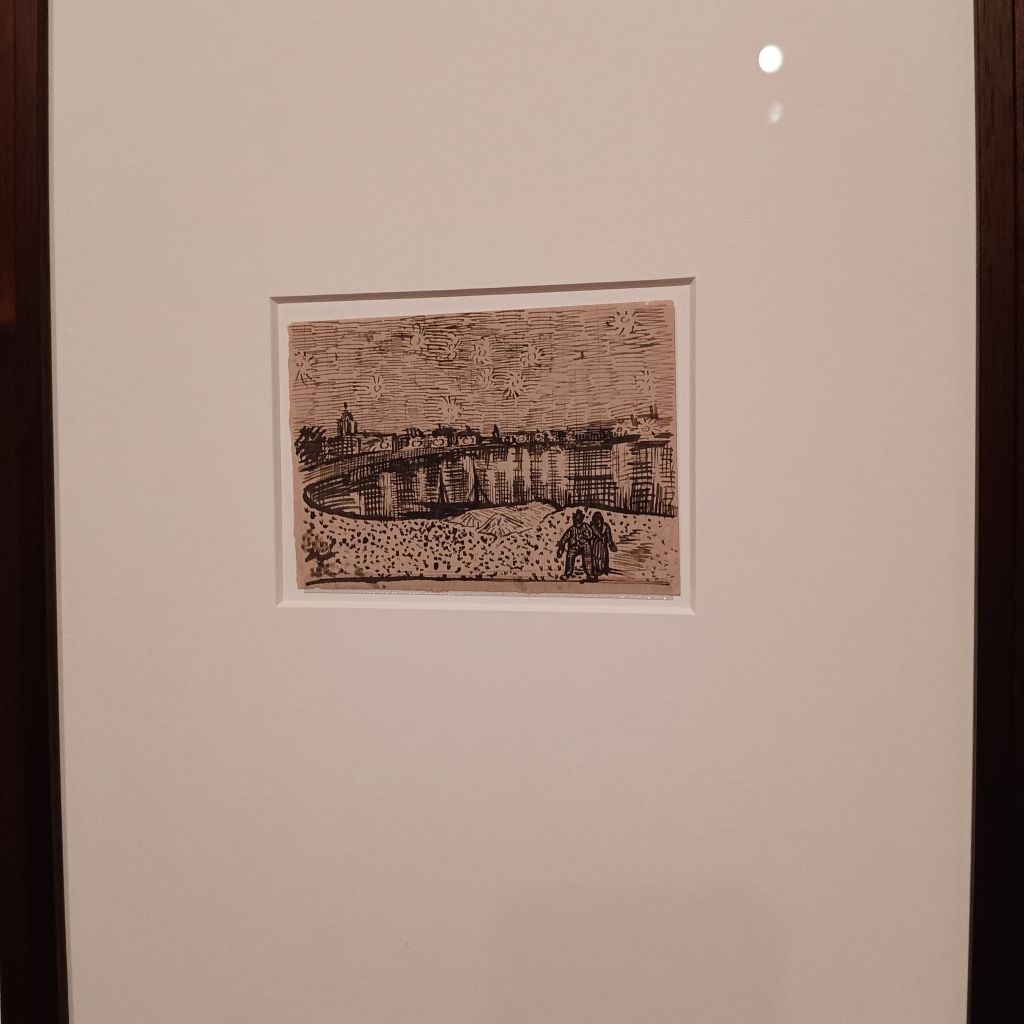

Interestingly, the Van Gogh paintings that were on show in Part 1 of the Kiefer exhibition were more convincingly argue. Kiefer though Van Gogh a rather unredeemed romantic but, unlike other commentators, he praises compositional design as his greatest achievement. This is why I suppose he chose to have Van Gogh’s design for A Starry Night next to his version:

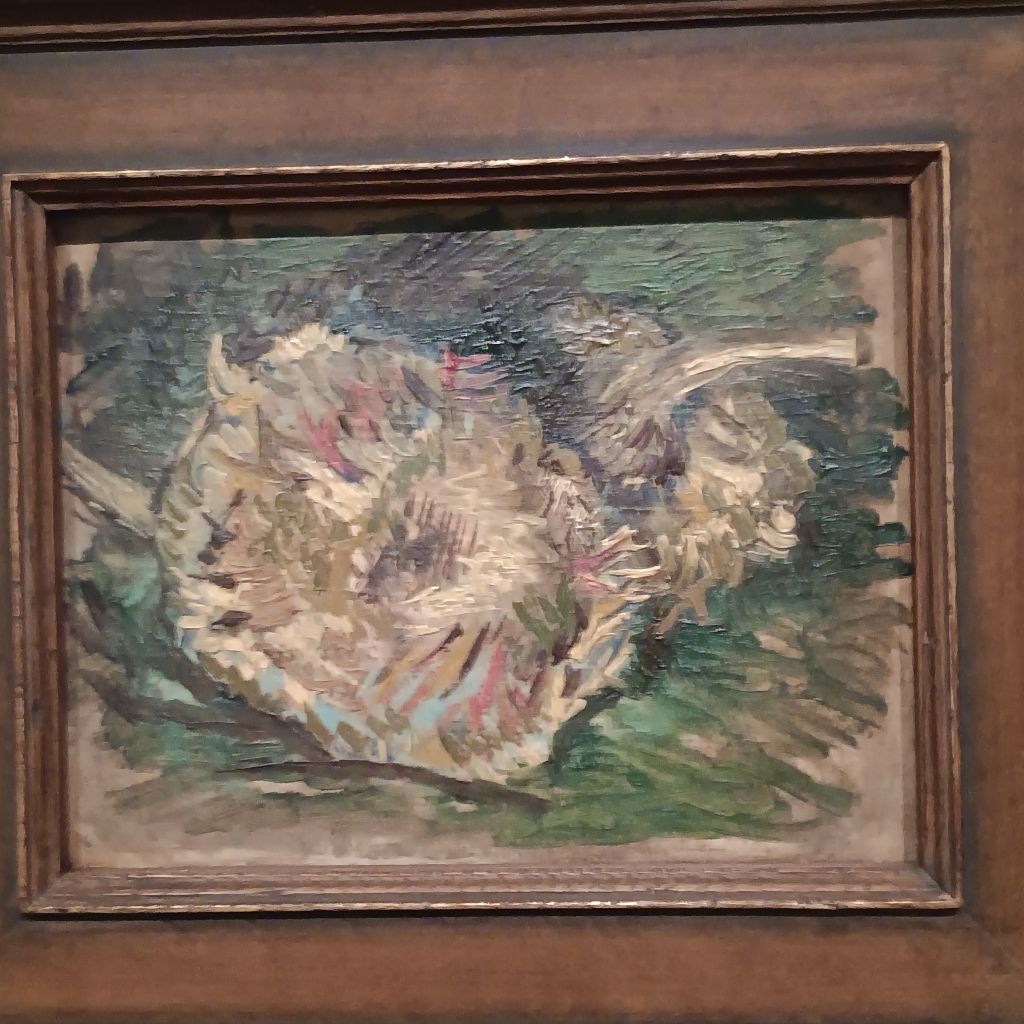

And more importantly this exhibition has raised to greater interest versions of subflower painting that do not fot the model usually used to explain these in Van Gogh, like The Sunflower Gone to seed below, which Kiefer uses in order to forefront his own toxic sunflowers (more of this in the next).

Ans above all Van Gogh’s wheatfields are seen again in Kiefer’s treatment thereof:

All for now. Still reading on Kiefer so the next two will be delayed – and moreover I have Sean Hewitt’s beautiful novel Open, Heaven to say my piece on next.

With love

Steven xxxxxx