On the myth that visiting the Rijksmuseum is the primary way of knowing the culture of Holland and the Dutch spirit.

In my introductory blog on our Amsterdam trip [at this link], I suggested there would be three more Amsterdam blogs to come. There, in the first version (now updated to reflect the chosen final title), I said these blogs would be:

- On the myth of the necessity of a Rijksmuseum

- On Van Gogh with the help of Anselm Kiefer’s eye

- On the true necessity of Anselm Kiefer’s insistence on art about something.

That first title was truly a confused one, given my actual developing intention, which was to write about the belief I had the Rijksmuseum would be the true object of my visit, as if that building and its contents stood as the true representation of Dutch culture and spirit. This however was not what I found

Much of our visit was spent in disappointment and resistance to what that institution genuinely offered, and hence I think I failed to see that iconic institution with anything like an answering empathy for its true glories which are without doubt greater than I could imagine from my tired visit.

Why? I ask myself. Why did I not gain from this visit either that which I hoped for nor some new illumination? I think a vast amount can be explained by our tiredness after our first day in Amsterdam – and our walk to the hotel on a day of extremely hot temperatures, that both continued in effect onto the next day of gruelling heat. Another contingent explanation, more personal than anything else, was the insistence of door security at the Rijksmuseum that I removed my badge in support of Palestine. I was so doggedly tired that I did it without question. The shame lingers even now.

But in truth, I think this was an occasion where failure to learn about the history of the museum was possibly at fault. It might have been a better experience, not only had I done so, but also if I had seen it in the context of the stormy conflict that its institutional smugness covered over, so strongly readable in the stormy romantic background spirit in the photograph below of the museum’s facade.

Wet days and stormy weather make the museum look embattled rather than smug in its sense of the massive achievements of nineteenth century bourgeois culture. To see the building in the flesh primarily serves to remove it from the iconic list of great national emblems, like the Parthenon or even the Gothic Fantasy of the British House of Parliament and put it in the third rate of global architecture, in my highly subjective evaluation, like the building it most recalls to me, the Victoria and Albert Museum. Both buildings rejoice in the smugness of the halcyon days of imperialist hubris. At least that was my impression, no doubt a faulty one.

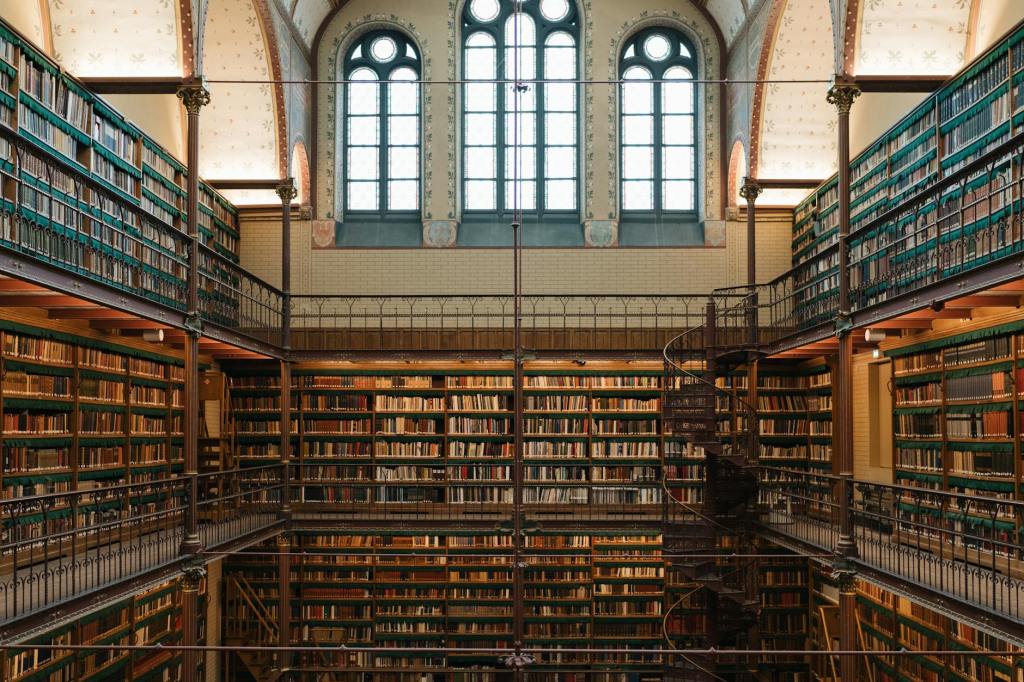

There are things I would like to know about the place, a highlight of the visit being seeing the library at the centre of its collections and the pit of the reading room for that library. The sense of supported scholarship is strong, strongly supported by the silence required in the gallery from which you look down the shelves of books to the deep reading room below.

But even in this place, there is a want of the requisite wonder, like that provided by the choice grandeur of the British Museum’s preserved central Reading Room with its echoic dome.

And then again, we came mainly for the Rembrandts, perhaps The Night Watch in particular. This represented a high point of my expectations since the undercutting realism of painting, has so ironised, via Rembrandt’s hand (as if he painted like Shakespeare wrote dramas), the civic pride of the seventeenth century rule of the Dutch bourgeois state. One sees it now only behind the glass front of a cage fronted physically by moving scaffolding used in order to support conservators from the museum, when they are there [which they weren’t on our visit]

The museum itself is conservatively curated around the periodised grasp of Art History, an approach strangely that flattens history under the weight even of selected artefacts, as in the British National Gallery in London. It is a method that causes that strange killing of interest in art for me, if looked at in the wrong way [ the only way possible for me on that tired day].

Strangely enough, there are signs that the curators at the Rijksmuseum themselves strain to find a way to make the experience of this great national and Imperialist collection live. There are immense burdens involved in representing a whole national culture, especially one prone to power that derives from international adventure, settler and other kinds of imperialism as do the cultures of Great Britain and The Netherlands.

Their current temporary exhibition is on American Photography, representing we are told, a wider project of the museum’s of collecting and interpreting of the history of this genre, that shows a less insular and less conventional and more networked philosophy of history than the main collection. In this sub-collection, gone are the reliance on period-based histories; though not to the detriment of the comprehensiveness of the commentaries on individual works.

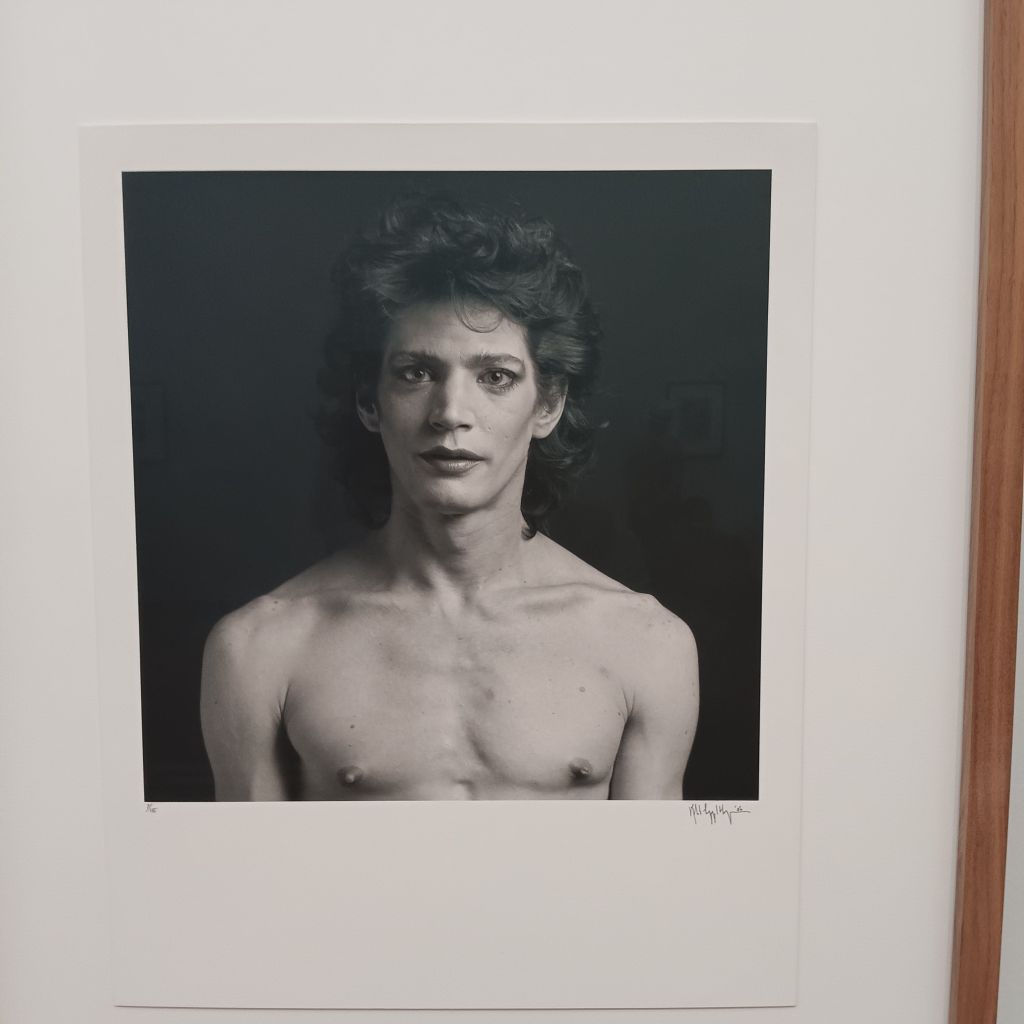

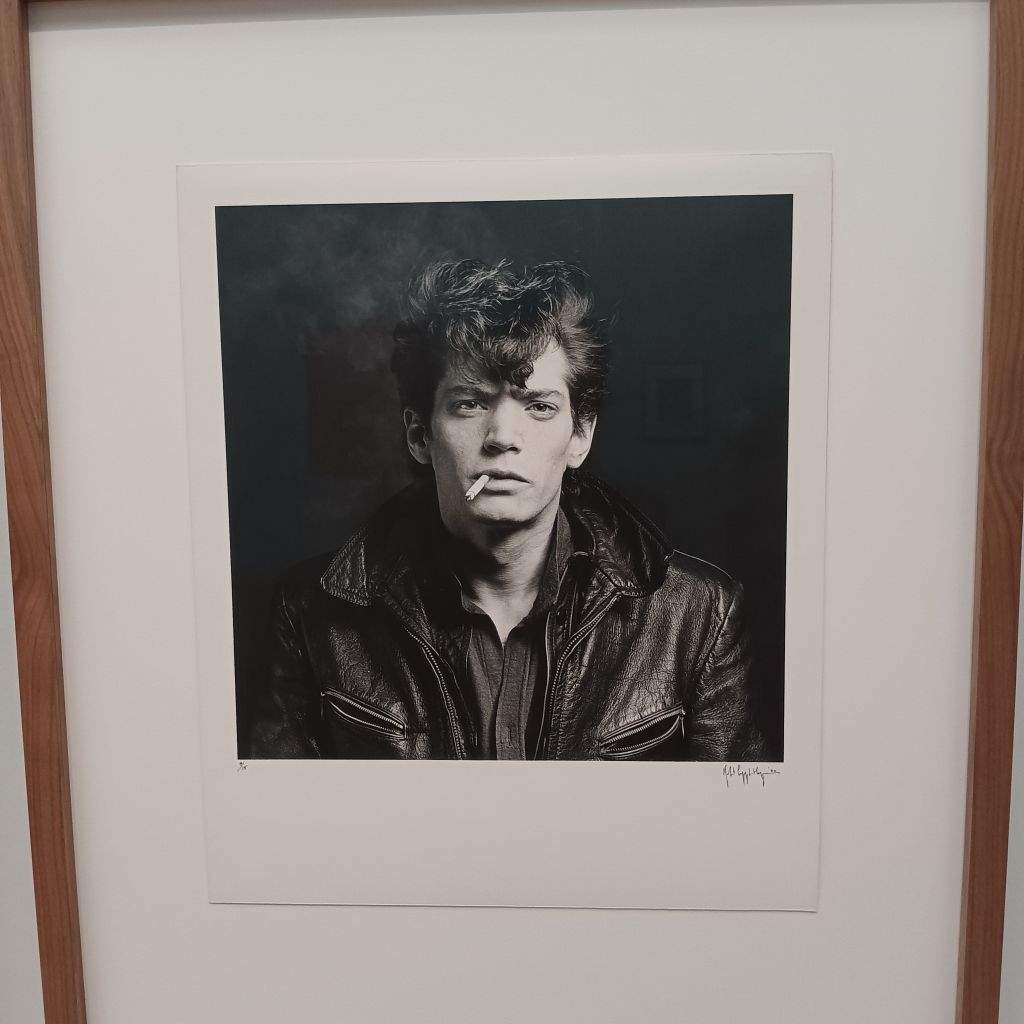

Hence, in these commentaries, what can be learned from the decades of the progressive elements in the history of photography is learned. Primarily, though, instead, the art is allowed to speak and create dialogues across what its imagery and iconography want to say. The photographs are allowed to tell thematic stories that cross history and art – about the nature of the interaction of chosen identities and contingencies across history and cultures, about the construction of race, queerness, marginality, oppression and resistance. Suddenly, the Rijksmuseum seems willing to cast off its cloak as mere representative of those things born, in Netherlander culture, those imposed on it (by Spain and Germany, for instance) and those stolen or imported. It was a strong exhibition but difficult to illustrate by examples, so let these suffice.

Record covers as applied photographic art and curated as socio-cultural evidence

The philosophy of identity, desire and the performative in two self-portraits by Robert Mapplethorpe

There is a fine catalogue of the above exhibition but on this occasion I did not purchase it. Again, I blame the monstrous tiredness both myself and hubby felt. The main collection suffered more from that contingency of state in us.

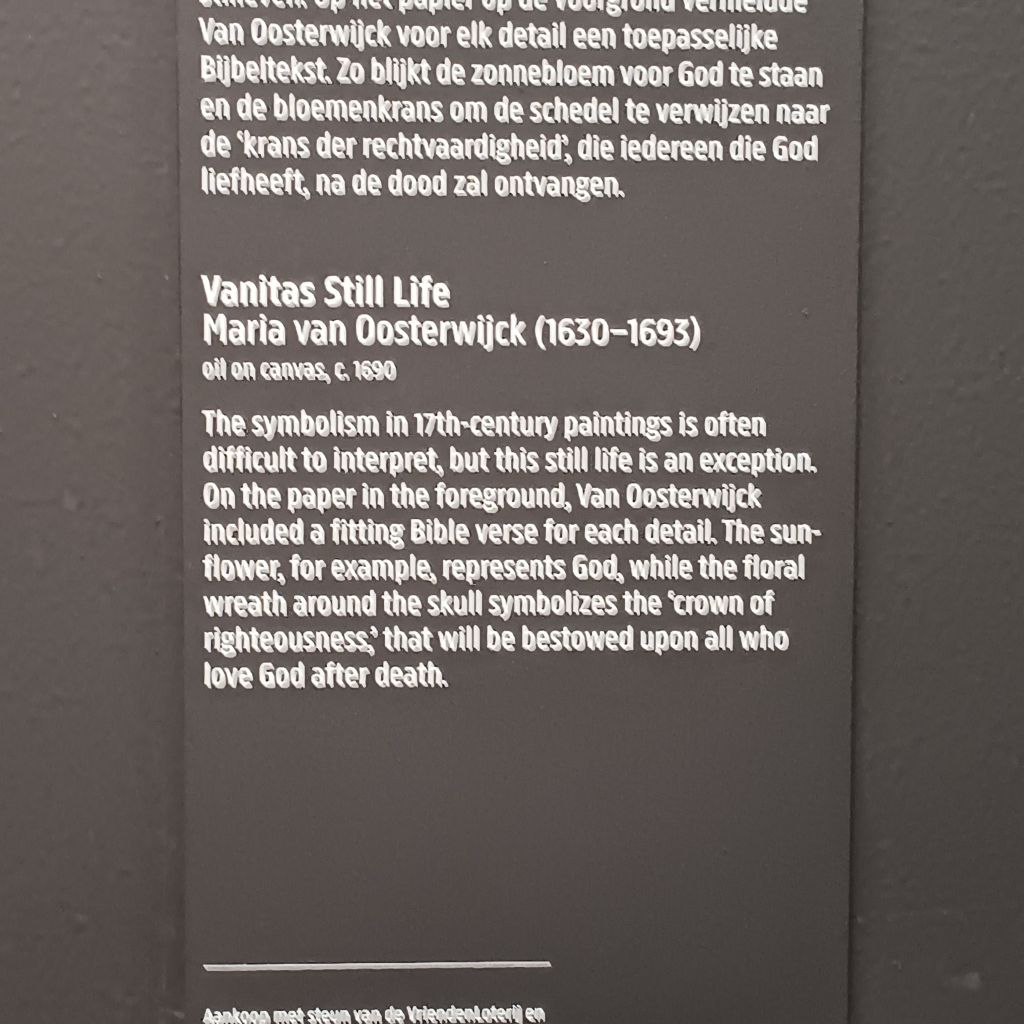

In the main collection, we confined ourselves to looking mainly at the seventeenth-century holdings, hoping to be bowled over by the starry realms represented by Vermeer and Rembrandt. And strangely that ubiquitous theme of the Baroque still life won through to me, despite the clonking commentary on its sometimes too easily misread interpretations (see my blog on still life in Spain, and other European traditions at the link).

The commentary on the rather stunning Maria van Oosterwijck’ s work barely touches its own painterly commentary on the contradictions in calling life vain through the excitation of our desire for the partiality for visual beauty.

When later I look at the sunflower iconography of Van Gogh through that artist’s eyes and those of Anselm Kiefer, I think I will remember well this use of a sunflower as am icon of both the Apollonian call to beauty and of the dominance of the gaze that this painting mimics. It demonstrates a dialogue about vanity but not one whose conclusion is entirely sorted. The empty sockets of the skull fail to competitively gaze out the eye even of a wilting sunflower.

Of course, then we proceed to Vermeer and Rembrandt. Vermeer is, I think, food for the eye that requires both alertness and willingness to see beyond surfaces, so I omit my inadequate responses to these – too few pictures really anyway. Moreover, I have in the past seen many more Rembrandts collected together to allow for excited comparative examination (see this blog – link here – of an exhibition in Edinburgh). Although there was food for that excitement, only one painting I saw re-excited it in me that day, and that I had seen before in The Edinburgh exhibition just referred to, The Jewish Bride.

Even from a distance, it is clear to anyone that this is not only a most beautiful painting but one about substantive issues of human action, cognition and emotion, as well as cultural history. It is almost the painting of ideas that dwell around words like appropriation, possession, and the complex nature of desire in human relationships. And it is done to a large point on the focal concentration on the interplay of hands:

The bride uses her hands in part to mitigate the proprietary claim made by her husband’s hand on her breast – one that presses on her and not over-sensitively – flattening it with his claim on it. Her hand establishes his in that position but also modifies it. I sense resistance here – a demand that the man sees what he is doing and makes his approach to her more sensitive. Her other hand, she holds over her genitals clutching a rich purse, formed in the shape (it seems of a heart).

Is this self-defence or submission. How does the theme of exchange of wealth for love and possession of the body interact with other signs that this picture is about the values involved in marriage or other amatory relationships. For wealth is the purchase prize of fleshly access here but also a defence against it – a barrier that keeps the mind of men on their appearance with the help of their wives.

This is all the more important because Rembrandt’s impasto treatment of clothes tells us that these clothes solidify like a shell around the vulnerable flesh of male and female, scaling it like chain-mail armour. And jewellery acts as much to interconnect and separate the fleshly hands (and turn them through rings into symbolic bearers of meaning that modifies their visceral grasp, but more so when the solid wealth of clothing becomes encrusted impasto.

As you can see this is small pickings from so charged (for me) a visit, but it was worthwhile. I have seen the Rijksmuseum now. It is not the primary key to Dutch culture but must, if I live for another visit, be seen on its own terms not on my mistaken expectations.

It depressed me somewhat that day though. But on the morrow I saw together Van Gogh and Anselm Kiefer. What riches there. Next blog on re-seeing Van Gogh through Kiefer’s eyes.

Bye for now

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxx

One thought on “On the myth that visiting the Rijksmuseum is the primary way of knowing the culture of Holland and the Dutch spirit.”