I think it must be being a film critic for I surely could not do a worst job than some! LOL. Or perhaps a comedian! Have you heard the one about the old man who in his youth survived a vampire attack that turned his friend into a vampire? One night in a bar, his health deteriorated his friend turned vampire comes to join him? The old man says: ‘I think that was the best day of my life. Was it like that for you?’ To which the vampire-friend replies: ‘No doubt about it. Last time I seen my brother. Last time I seen the sun. And just for a few hours, we was free’ . Malcolm Bradshaw, the film critic for The Guardian, I am told, says he thinks Ryan Coogler’s Sinners would be a better film without the ‘supernatural element’. Yet this is the first film ever to understand the beauty of the mythology of the vampire in a way that matters. This blog tries to say why.

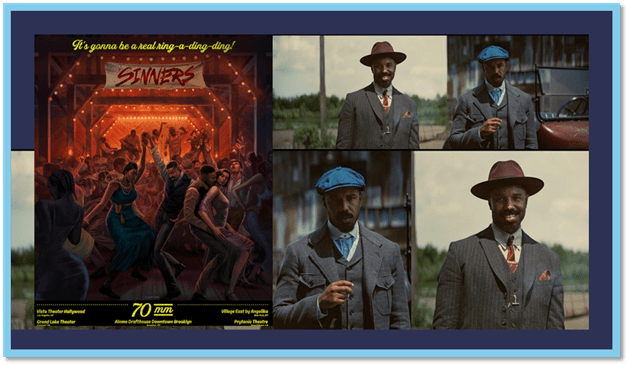

First of all we need to dispose of the silliness of what I believe Malcolm Bradshaw to have said when he reviewed this film, for I am told (by someone usually reliable) that Bradshaw thinks that on balance this film would be a better one if it had no supernatural element – just as perhaps Macbeth or Hamlet might be better plays without dubious witches and/or ghosts. Wikipedia, reliable here as usual, describes the film, without shying from the fact that it would be another film entirely if it were not, as it is, an ‘American horror film written, co-produced, and directed by Ryan Coogler. Set in 1932 in the Mississippi Delta, the film stars Michael B. Jordan in dual roles as twin brothers who return to their hometown to start again, only to be confronted by a supernatural evil’. So far, so good, although even this makes assumptions about the film’s treatment of ethical or spiritual evil that aren’t that necessary to make.

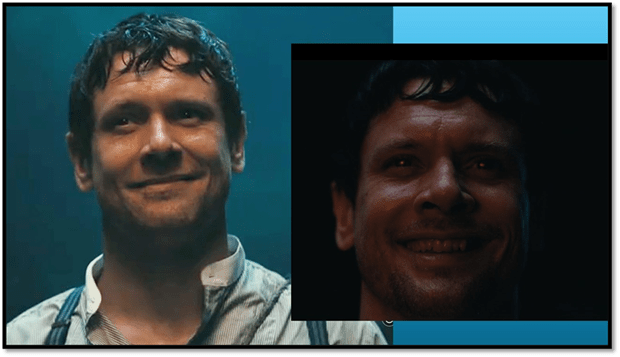

There are vampires aplenty in the film by the end although originally only one; Remmick, a man who though originally having a Southern drawl, later becomes entirely Irish in dialect and cultural presentation, for reasons we will explore later and throughout. Remmick is a vampire capable of international status, given that he has already been undead for 600 years. Throughout his vampirism is seen as a creed attached to marginalised cultures (hence the Scottish and Irish ditties and accents). They desire to have Sammie ‘PreacherBoy’ Moore (played and sung brilliantly by debut big-time actor Harry Caton) more than they want access to other characters in the story.

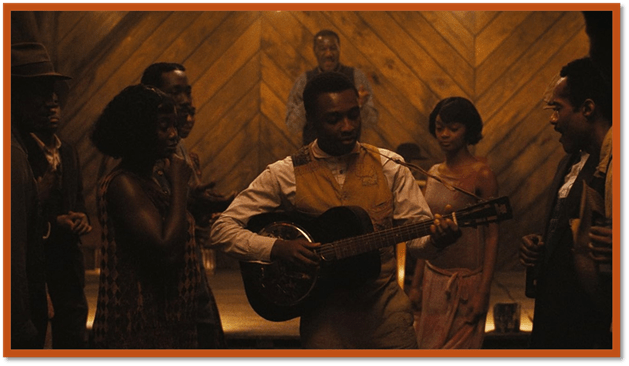

That is because his songs evoke the vulnerability and resilience of marginalised cultures, and their myths are played beautifully. He sings in a way that calls forth marginalised peoples (even drag queens) in his first chance to sing to his own guitar in the Black Community Juke Club set up by Smoke and Stack. They come from the past, present, and future. These time-crossing, cross dressing groups create some of the most magical scenes I have ever seen in a film and made me feel I began to understand the Blues music used in the film as I never have, as someone unattracted to it previously.

The vampires of this film are the bearers of choric music and lyrics, continually communicating with their victims as initiates of some religious mystery. The theme of these lyrics relates to the search for a community beyond division but also beyond the possessive relationship we call the couple (a theme throughout the film). That last mentioned theme is also the theme of Will You Go Lassie Go!

Will ye go, Lassie go?

If my true love she'll not come

Then I'll surely find another

To pull wild mountain thyme

All around the bloomin' heather

Will ye go, Lassie go?

And we'll all go together

To pluck wild mountain thyme

All around the blooming heather

Will ye go, Lassie go?

And we'll all go together

To pluck wild mountain thyme

All around the blooming heather

Will ye go, Lassie go?

Interviewed in 2025 by Claire Valentine McCartney for M Magazine online, the actor who plays the starry-eyed vampire leader, Jack O’Connell, attributes to himself the impetus to introduce this song to the film. It’s a song usually available on Irish labels but described by O’Connell as a Scottish song, increasing the mix of alienated and marginalised cultures that the vampire horde in the film enact. Its beauty is that it cocks a snook at romantic coupledom in the lines ‘If my true love she’ll not come / Then I’ll surely find another’. Thence the song becomes about communal togetherness.

The second theme, already latent as O’Connell knew in the Scottish song, is one that the director Coogler already had in the script O’Connell read before accepting the role. It is that theme of togetherness – cultural bonds that militate against oppression in The Rocky Road to Dublin, which ends with a migrant Irishmen, locked out of his own community and drifted to Liverpool, finding strength from the support of Galway lads, against the racial branding coming from the ‘Liverpool boys’:

The boys of Liverpool, when we safely landed

Called meself a fool, I could no longer stand it

Blood began to boil, temper I was losing

Poor old Erin’s Isle they began abusing

“Hurrah me soul” says I, me Shillelagh I let fly

Galway’s boys were by and saw I was a hobblin’

With a “lo!” and “hurray!” they joined in the affray

Quickly cleared the way for the rocky road to Dublin.

The vampire theme takes up then this communalism of shared marginalised cultures, and for me it is a beauty of the film. The vampire Remmick sometimes presents himself as a redemptive force for the marginalised, although not you might notice for the Native Americans who we first see on the hunt for him as something that is ‘not as he seems’. As the vampires close in on the now near empty Juke club, now abandoned by the majority of the Black community who were loving its togetherness, in fear of their lives, he says to Smoke:

Remmick: I am your way out. This world already left you for dead. Won’t let you build. Won’t let you fellowship. We will do just that. Together. Forever.

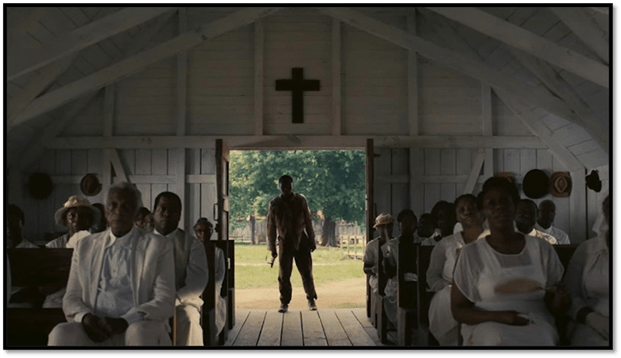

This is an illusion of course, in one way, for the vampires seem mainly to want to feed of those who let them in (and we know you must only ever ‘Let The Right One In’ from other vampire art. The vampires may playact, and brilliantly playact, cultural cohesion and togetherness but they are essentially bound, in dark humour of this trans-genre film – musical, comedy, horror, thriller, social realism at some points or all of these together – only to the common factor of a vampire culture straight out of the B-Movie horror tradition – killed by sharpened wooden stakes, and sunlight at daybreak and dependent on others breaking the barriers down that exclude them – don’t let them in. Their only connection to the marginalised is perhaps only in that reality of being kept out of normative society, or its fringes, by exclusion and closed doors. Doors open and closed or well or badly guarded by ‘bouncer’ material, are a central feature of this film from the let go when we first see the now outsider, Preacherboy now scarred with the scars, perhaps the sign, of the Beast of Revelations, open the doors into his father’s church clothed like a whited sepulchre and bearing in that its denial of Blackness.

But nevertheless in this film things are never so simple, and the director remains tight-lipped about his intentions with regard to allegoric or symbolic meaning attached to vampirism – but it is noticeable that one stereotypical feature of the stereotype film vampire is missed out of this film. Christopher Lee’s Dracula only ‘turned’ into members of his community only selected victims – in Sinners anyone bitten becomes part of that community, sharing each other’s thoughts and personal, social and racial cultures. McCatrney quizzed O’Connel about his discussions of this with Ryan Coogler, the director and scriptwriter, perhaps aware of latter’s, reticence in doing so: asking about the fascination with outsider music that formed communities on the margin out of music and dance traditions. McConnell answers:

We spoke about it quite a lot. It’s about the sharing of ancient cultures and customs, be it within music or within language. It’s that migration of people, and the similarities between them. It’s impossible to put a precise start date on these cultures sharing things, but more recently and more localized for us would be the melting pot that was within the South, with African peoples, Irish and Scottish peoples, Europeans—all of them bringing these ancient forms and traditions with them.

For an Irish actor with a foot in Scottish culture too, this must have been a gift that opened up pathways between the performing arts he was willing to master, as he does riverdancing in the film:

Obviously, I wanted to know about “Rocky Road to Dublin” and what that was doing within this piece. I wanted to know about the Irish dance, and I was massively surprised to find out that Ryan was going to try and do the genuine, traditional Irish stuff. He caught me off guard. But once I knew that he was down for the real deal, I thought, “Count me in.” It suddenly made sense.[1]

I think no-one will convince me that the vampires hold a powerful weapon in the idea of a communalism that militates against the isolation of the enforced migrant: from the Irish in Liverpool to the oppressions of American Jim Crow culture and the white laws that demonised it, so often referred to in the film. But note that Black Community of the film do not altogether trust white people (even the Irish) who promise to transcend the division of skin colour. Of course Remmick is charming, though in our first vision of him he is a racist colonial settler out to demonise good people who are also Native Americans. But he scrubs up well:

With prosthetics however come moments of revelation, that stat with the red eyes glittering in the dark, as in the portrait on the right of the collage above, but end up toothsome and bloody, in both the case of Remmick and other border crossers, like the mixed race Mary (on the right below) who whatever her fascination for Stack, her ex-boyfriend, likes to pass as white, a trait Stack even tries to help her – or so he says – to accept (by initially abandoning her). By this time the vampire is nearly all stereotype, without charisma nor beauty. Were the communalists fooling the Black community all along?

Perhaps, but this would be to deny the importance of the role of Harry Caton’s Sammie Precherboy Moore character, whose beauty of voice, person and instrument – all broken and scarred in the end do to motivate the film, from his first accompanied monodramatic song that invokes all cultures to the dance floor – past, present and future:

This is a beautiful dream. When scarred by the clawed Beast of the vampire, he almost succumbs to his father’s preacherly, oppressive but genuine love to believe that if but he drops his guitar and stops inviting in the spirit of secular communal art, he will be free – but he knows lie all the other Black people clothed in white in his father’s church he will be in chains, and willingly so:

Hence the importance of that infamous scene, which we almost missed in our rush from the cinema, that I cite in my title, where Sammie is now played by Buddy Guy:

Old Sammie: You know something? Maybe once a week, I wake up paralyzed reliving that night. But before the sun went down, I think that was the best day of my life. Was it like that for you?

Smoke (as Stack): No doubt about it. Last time I seen my brother. Last time I seen the sun. And just for a few hours, we was free.

The issue is that freedom remains illusory and temporal in this film, and often experienced at the height of oppressive circumstances. In such circumstances the oppressed are not solely victims but ‘turn’, not into vampires necessarily here, but to be the icon of the resilience of their community culture, as old Sammie has been as the mortal bearer of his musical skills in Blues music and will be to his death.

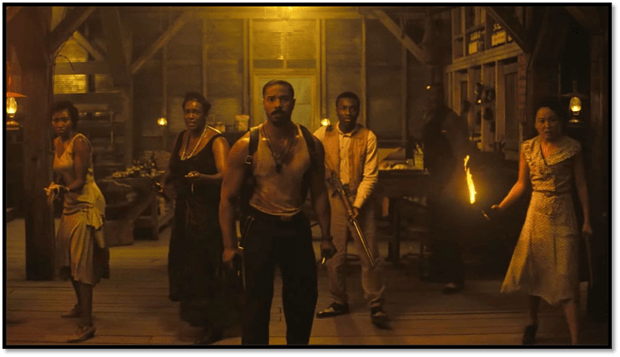

I puzzled at why the quote from the film collector attributed the last film to Smoke as Stack. I think they might be right though. Smoke and Stack are both parts of the same Smokestack, a chimney in the United States designed to take foul waste gases from industrial processes to less visible but still present heights. Smoke and Stack are beautiful people (in fact one person (the brilliant Michael B. Jordan) – since both played by the same man by virtue of AI trickery) but even together are really only a release valve for the Black community and like the smokestack industry really there to just to make money out of their own people, despite the nuance of their nobilities. Their role is to sell Black culture not to develop it and to mix gambling and prompts to drunkenness with fun, art and folk culture.

Michael B. Jordan with much panache and subtlety of detail and differentiation clearly aims to find the ethical beauty of these ex-Vietnam-Veteran gangsta boys, not least in their love for each other and their cousin, the Preacherboy – they are all named Moore by last name..

I think Ryan Coogler is right to keep silent here about the nuances of this film. The brothers can appear as in union all the time but the meticulous realism of the opening story shows that their values are really divergent. It is Stack that realises the beauty of Sammie’s voice as he listens to it in the car he uses to transport Sammie to the Juke Club and this scene is remembered in the final scene to represent the last day of freedom. But Smoke has less access to softer emotion. He shoots two Black young men he thinks are stealing from him and is much more invested in the gambling and drinking than the music of the club. The last time we see them together in a fine example of AI trickery, they are standing guarding the door against the three white vampires (apparently though here only three poor whites). The scene is typical of the treatment of access and the interplay of inclusion and exclusion in in the film’s themes. As the door opens the poor whites are revealed behind it.

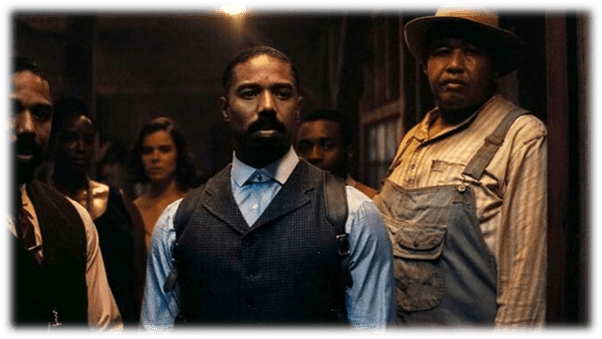

Framed by the door that excludes them these people appeal to our and the Juke Club’s charitable feelings, alone in the dark with only one lamp to light them, they seem kith and kind but for their colour. Yet Smoke and Stack know that it is an error to trust white words.

At the other side of the door, they with their bouncer (Omar Miller is fine as Cornbread, a sharecropper, a cotton worker who might as well be enslaved so tied is he to the white management and profiteers of the crop) stand finely trim in gangsta or dealer costume, barring the way, with whit-passing Mary looking over their twinned shoulders.

Cornbread paradoxically is brilliantly played for his Jim Crow stereotypical appearance belies him when he becomes a vampire when he goes out to relieve himself and finds he cannot return and must ask with uncharacteristic and upper-class-mannered politeness. He defends this new characteristic as a new access to human politeness, offering it to other insiders as a shareable characteristic if they let go of their black separatist defensiveness. It is finely conceived all of this, making the audience a viewpoint always the other side of the door whether we are outside or inside and knowing that transit through it has its barriers other than the physical door but also, should we pass, its dangers.

When Stack is turned, Smoke reverts to military style in defending portals, as here:

Later that tough man act is in its entire beauty when we share (or at least I did) the command-type vengeance he takes on Hogweed, the Klu-Klux Klan leader who had sold the barn to Smoke and Stack (it was actually a slaughter house with stained floors). David Maldonado plays Hogweed in a way that makes our sense of white duplicity fully realised.

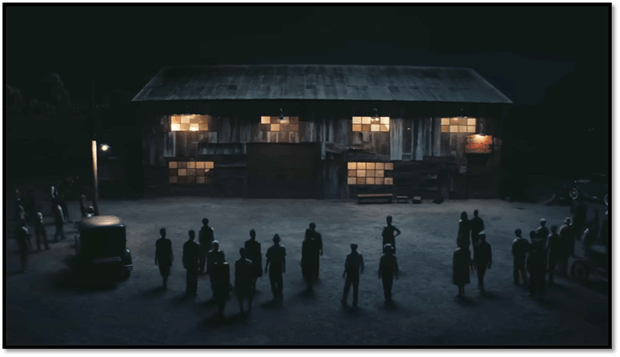

It is at the first point however when guarding the door as front-line leader that the beautiful scene of the vampires ringing the Juke joint occurs and they sing to the insiders the joys of being taken in, in that wonderful piece:Pick Poor Robin Clean, originally sung and played by Jack O’Connell, Lola Kirke, and Peter Dreams, when, as Remmick, Joan and Bert ,they arrive at the juke joint. The song gets continually and haunting repeated. It is a vile song that plays with the Jim Crow characteristic that fuelled racism, though having an appeal to vengeance takers against white supremacists. That characteristic threatens their female family, parodying the beliefs of the KKK:

Get off my money and don't get funny 'Cos I'm a nigger, don't cut no figure Gamblin' for Sadie, she is my lady I'm a hustlin' coon that's just what I am Well didn't that jaybird laugh When he picked poor robin clean Picked poor robin clean, poor robin clean Didn't that jaybird laugh When he picked poor robin clean Well I'll be satisfied having your family

In this scene windows play the role of lighting up the virtues of being an invited insider, although the blues singers enchant its over-cosy heart, for after all as Delta Slim (Delroy Lindo), the impoverished multitalented musician, colourfully says: ‘See, white folks, they like the blues just fine. They just don’t like the people who make it’.

Smoke plays fast loose with offering two-way entry of his suspicion but also attraction to white in his black through his turbulent relationship with passing-as-white Mary as in this exchange:

Smoke: Well, I told you to stay the fuck away from me too but I guess you didn’t hear that part, huh?

Mary: I heard you. I heard you loud and clear, but then you stuck your tongue in my coos and fucked me so hard I figured you changed your mind.

In turn Mary pours drool from her mouth into Smoke’s in a charged erotic episode: Smoke: [as Stack] You droolin’. Mary: You want some?’ Then from the top she obliges. The point about the brothers is that Smoke playacts Stack when it is to his advantage – sexual advantage here.

However, here are plenty of contradictions in this film. In no way has it easy answers about the nature of the right response to oppression though many alternatives are played with – trickery, military or muscle challenge, attempts at co-existence or a rainbow alliance created out of oppressed people. Strangely give what appears (from report) to be a largely unintelligent review of the film by The Guardian, the much maligned online Review Geek has good things to say. Here they describe the musical variety in the juke joint:

Where Caton’s song is seductive but hopeful, Jayme Lawson’s number is sultry and animalistic, sinful and sinister as the vampires start their scheming. But there is no lull in the story as even the final act begins with an adrenaline-filled number aka the evil Irish jig. The symbolism and the irony won’t be lost on the audience as Black characters surround and hype the Irish instigator – two races united by their shared colonial experiences.[2]

There is no way that animal imagery is used simply in this film, even when dealing only with appetites. The binary human / animal has the fate of that of the male and female though they are somewhat sustained. The need to sustain the binary of Black and white is a big issue in the film’s treatment of inclusion issues. What, however, did Ryan Coogler intend? Asked that by McCartney Daniel O’Connell said:

I’m probably going to take Ryan’s lead and just kind of agree that any metaphor within the story is in the eye of the beholder. As an actor and an artist, I’m always looking for hidden meanings and intellectual answers, so that’s not to say that they’re not deliberately put there. I definitely had my takes. But they’re so open to interpretation, and I respect Ryan for not really wanting to be too explicit about it.

And if you think about it this is, a Gothic film not only because of vampires but the troubling theme of the doppelgänger, although it tends to treat that theme in terms of a social comedy played through the one duplicated character Smokestack. It is suggested even in the poster on the left in the collage below (repeated from earlier). Smoke and Stack seem variously to exchange roles – in part for sexual play, in which Mary is involved. This is never, as far as I remember, a feature of the spoken plot but it is the only way I can reconcile the frequent mistakes I make in the cinema (and above no doubt) in identifying the particular agency at work in Smoke and Stack’s exploits. It seems that sometimes these distinct characters can take on the other’s traits, like the vampires in the film who do so as a matter of course with the communal telepathy, especially over their sexual behaviours of women.

The poster on the left seems to show one red eye (I) doubled into the red and blue of Smoke and Stack. This is an amazing film and the doppelgänger theme is the very icon of the a being that has two or more aspects that claim commonality. But thus is the nature of any allegory or symbolism of this film. After the magic dance where past, present and future of different cultural traditions there is a scene in which the whole structure of the Juke Joint burns down and outside and inside exist no longer. That annihilating fire might mean any number of things from destruction to creation, from revelation to obscuration, or light and dark. I do not even make a guess though that scene stays away. So much am I unsure that I desperately need to see the film again – not in order to determine the correct interpretation but to open me up to the polyvalence of its possible meanings even more.

This is a film you just must see. It will become a cult film but it is a more appealing film than this suggests – which starts as a parable of Black Community existing under oppression in fairly social realist terms but ends as more universal than anything I have seen, heard or been bombarded by. The score hits you directly and is thoroughly part of the human-cum-animal-cum-supernatural drama.

See it, please.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Claire Valentine McCartney (2025) ‘Sinners Star Jack O’Connell on Playing an Irish-Dancing Vampire in Ryan Coogler’s Hit Film’ in M Magazine (online) [April 29, 2025] available at: https://www.wmagazine.com/culture/jack-oconnell-sinners-remmick-irish-dance-interview https://www.wmagazine.com/culture/jack-oconnell-sinners-remmick-irish-dance-interview

[2] Sinners (2025) Movie Review – Is it really that good? | The Review Geek https://www.thereviewgeek.com/sinners-moviereview/