Of course it is Donald Trump! But why argue with a manipulator. Instead here’s a political parable. Pushkin’s namesake in his play ‘Boris Godunov’ threatens the Russian state with a fundamental question about the true nature of political power, as Pushkin saw it in the early nineteenth century: ‘…, dost thou know / Wherein our true strength lies? Not in the army? / Nor yet in Polish aid, but in opinion – /Yes, popular opinion’.

My copy of ‘Boris Godunuv’ from 1986.

Pushkin knew his English and French history. Before he wrote Boris Gudonuv, he studied the representation of historical power struggles in Shakespeare’s History Plays. Yet, a man of his time, his play was cognizant of the later English Revolution and of the role of the People in French and American history. Boris Godunov was banned until 1866 in Russia. In it, the absolute monarchs of the Romanov dynasty saw the danger to their own state of a public that no longer believed in the divine right of monarchs to rule and saw instead the oppressive machinery by which rulers kept hold of absolute power. Boris Godunov takes as given that the right to rule is legitimated not by birth or some right derivable by divine order working through created nature, The play opens on the 20th February 1598 with two minor princes of once-royal blood comparing their right to the throne to the present contender for rule after the death of the son of Ivan the Terrible, Godunov, who is yet they argue of lower birth than they with their ‘nobler lineage’:

A slave of yesterday, a Tartar, son

By marriage of Maluta, of a hangman,

Himself in soul a hangman, ...

Thus history recognises that kings may rule de facto through oppressive violence and murder of their rivals, but what this play has – which Shakespeare never uses as so fundamental, is the idea born of revolutions in Western Europe, is that the arbiter of right to power is not birth and inherited grace through God through the levers of birth but by the will of the people ruled. The people’s will can be shaped – and these minor princes know the means – the ability to ‘bewitch’ the people ‘by fear, and love, and glory’ – but also know they do not posses them as Godunov enough does with the ability to draw fear by oppressive use of power, love by false promises and glory from spectacle.

All of these strategies, Shakespeare recognises as strategies that aristocrats or other self-constructed ‘natural’ leaders use to bolster their legitimacy in power struggles, but Pushkin in a later age, the flares of liberation thinking still attached to Romantic nationalism recognizes another principle – that the source of power is not a blend of blood lineage posing as God’s choice, popularity and Realpolitik but absolutely depends on the will of the people.

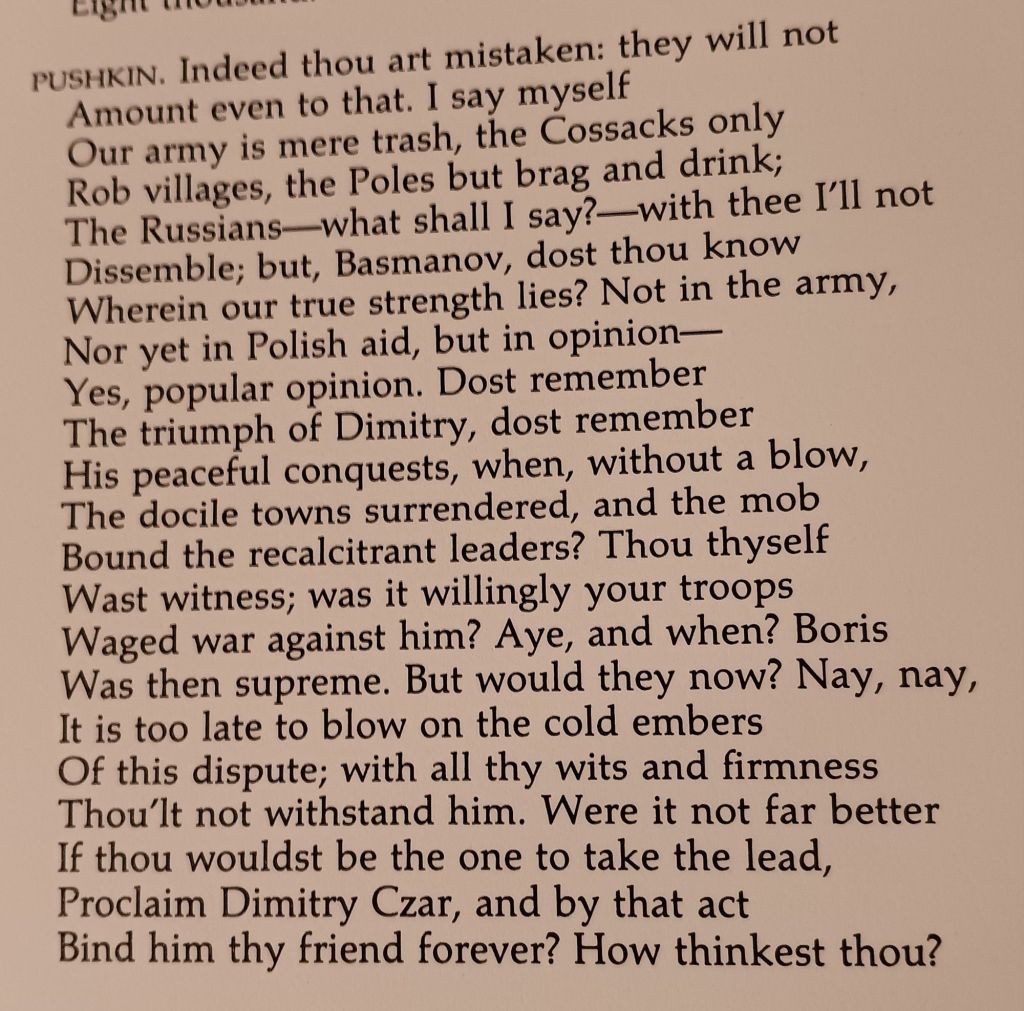

Yet it takes the whole of the play – or the Mussorgsky opera (which I have never seen, alas!) to get to this. In this scene the noble Basmanov (who has pledged himself to Godunov’s son and heir – Feodor) is persuaded by the rebel lord, Pushkin, to reject Feodor and turn to the rebel Pretender to the throne Dimitry – who everyone knows by then is not even Dimitry but a lowly monk pretending to be the dead Dimitry – the murdered (by Boris Godunov) youngest son of Ivan the Terrible. This is despite the fact that Pushkin and Basmanov know that the military might of Boris is far greater than the Pretender’s, who number no more than 8000. Pushkin (both of them I think) speaks:

The issue here is that the strength even of pretender monarchs is the people itself – not only that but that invention of nineteenth century political and economic thought, unknown to Shakespeare: ”popular opinion”. In our age of the bloated orange pretender, Donald Trump, we ought to be aware that the people can empower fraudsters – elect their natural enemies – but that is because they lack self-belief in themselves as the People. Those nobles in the beginning of the play) think the people’s only power is to elect but their speech must have made the Romanov Tsars of Russia thick blood of lineage run cold:

... Let them turn from Godunov;

Princes they have in plenty of their own;

Let them out their number choose a czar.

What is the issue here! Are the people still so limited in their power that the one they chooses must be a prince’, though one of their own’ whatever that means, or is Pushkin seeing what these courtiers do not see – that the People may pick from their ‘own’ regardless of the blood-line of their choice. They will hold power in representation of the People not as their natural overlord – as was believed to be the case in The English and French revolutions, which Shakespeare never saw. It is important in this play that the Pretender is no lord seeking to steal the legitimacy of an earlier monarch whose legitimacy was thought sacrosanct – as Henry Bolingbroke does of Richard II, and another Pretender, a Tudor, of Richard III – still on the basis of noble blood but a poverty stricken monk, who knows his dream of absolute power is chimerical and depends entirely on the social psychological favour of the ‘people’. The monk Grigory, who will take on the role of Dimitry, is dreaming of power even whilst still an Orthodox monk in Chudov monastery in 1603 but his dreams of elevation are based on the fear of the people seeing through his claims to the ascent to power

... I dream I scaled

By winding stairs a turret, from whose height

Moscow appeared an anthill, where the people

Seethed in the squares below and pointed at me

With laughter. Shame and terror came upon me -

And falling headlong, I awoke.

Power comes to individuals in their self-belief that they can fool the people that it is NOT the People’s power that makes kings, or orange presidents. Pushkin’s play is I think entirely about this contradiction in the nature of power – that lies have to be believed – even by the liar (hence the Trump analogy) . Once he has become Dimitry there is no way that person can return to being Grigory the monk, even less of the highly sexed man who only wants one woman to believe in him. He is convinced of this when a true Princess tells him that she will have him only as long as he can successfully represent their communal will to power. Since she will not marry a nobody, even if the somendy she has to marry is a nobody pretending to be a somebody, she persuades him into self-belief in the lie of his own claims of royal; blood and divine right, and calls him Czarevitch, the son of the true czar. In outlining her argument, it is also clear that being a ‘man’ is equally an act for most males (we are not far then from themes in Eugene Onegin, the Byronic masterpiece of Pushkin’s):

... Czarevitch, stay!

At last I hear the speech not of a boy,

But of a man. It reconciles me to thee.

Prince, I forget thy mad outburst, and see

Again Dmitry.

This remains a Russian play and we are a long way from Revolution – even the White revolution Pushkin would have favoured. But the whole tenor of this play is that the holders of present power spend most time fooling the People that their strength does not constitute their own right to democracy. Pushkin recognizes that the aristocracy have power solely because they stop the people seeing that czars are merely symbols of their own power if they would only think straight. meanwhile, like the Trump cabinet they keep fooling us, and we allow them to do so. Prince Shuisky boasts of that power of deception he sees as his entitlement, when he senses the danger of nobles testing the evidences of the divine right of kings:

... Even now the people

Sway madly first this way, then that, even now

There are enough already of loud rumors;

This is no time to vex the people's minds

With aught, so unexpected, grave, and strange.

I myself see 'tis needful to demolish

The rumour broadcast by the unfrocked monk;

But for this end other and simpler means

Will serve. ...

In this play the people look to a means of becoming the meaning of history’s onward march but, of course fail, because the status quo holds all the cards.

TRump know that too. Oh! How long will history stay in its present regressive state.

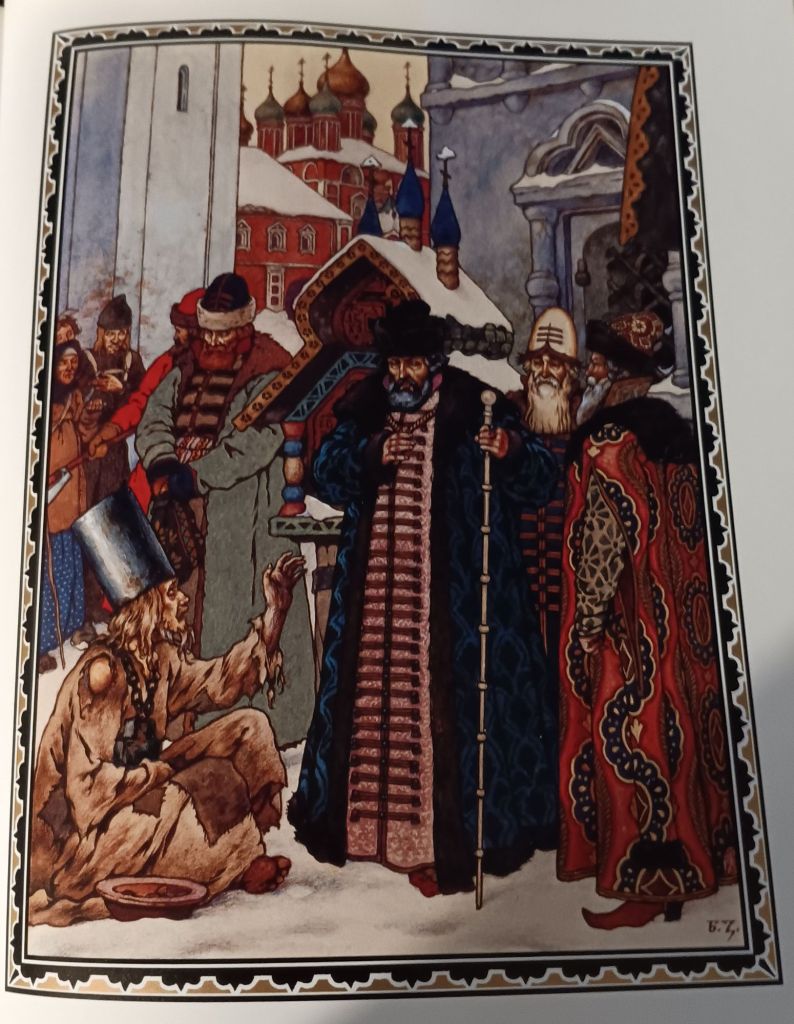

Boris Zvorykin’s illustration of Czar Boris flanked by representatives of Church and State contemplate a poor beggar’s views of the legitimacy of his supposed power.

Bye for Now

Love Steven

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

PS How long will the People of the USA bear to be so egregiously fooled?