The question today is full of Unstated assumptions about the word ‘nervous’, even if we grant that it is older meaning in thr history of the usage of this Latin-derived word in English is obsolete which I can’t quite admit. Here is the point about the word in etymonline. com:

late 14c., “containing nerves; affecting the sinews” (the latter sense now obsolete); from Latin nervosus “sinewy, vigorous,” from nervus “sinew, nerve” (see nerve (n.)). The meaning “of or belonging to the nerves” in the modern anatomical sense is from 1660s.

From 1630s it was used (of writing style, etc.) in the sense of “possessing or manifesting vigor of mind, characterized by force or strength.” But the opposite meaning “suffering disorder of the nervous system” is from 1734, hence the illogical sense “restless, agitated, lacking nerve, weak, timid, easily agitated” (1740). This and its widespread popular use as a euphemism for mental forced the medical community to coin neurological to replace nervous in the older sense “pertaining to the nerves.”

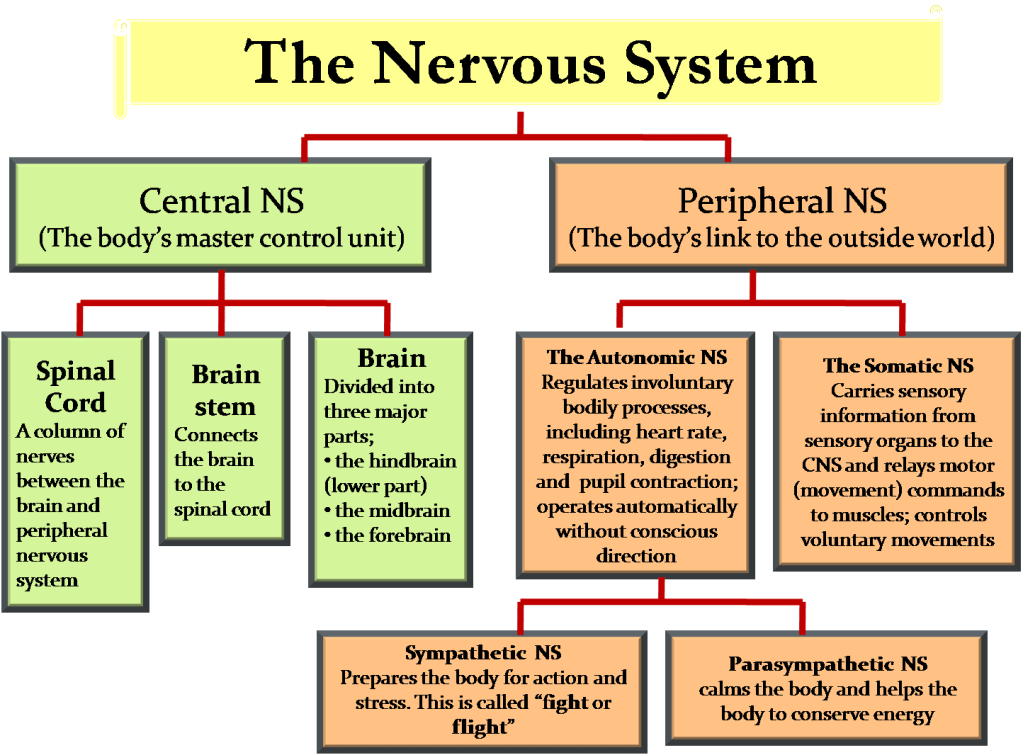

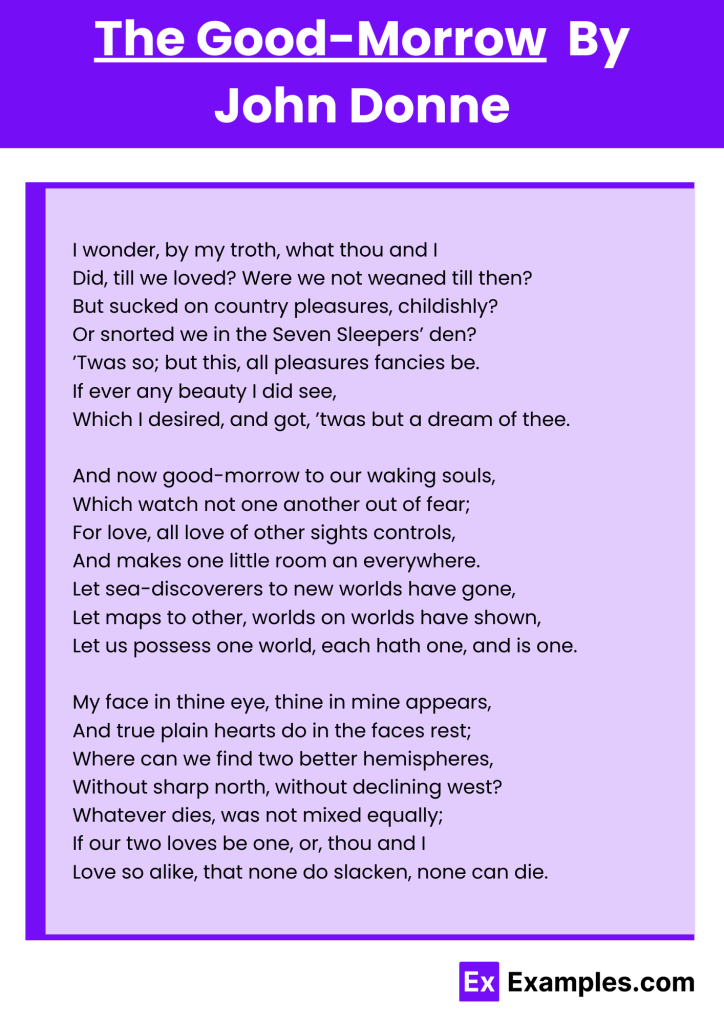

Anatomically, the nervous system of any animal is multi-functional, though operative usually under the radar of our consciousness. It organises every activity of the animal body, however simple the animal, most of which are motor ans autonomic functions, as well as complex behaviours. Despite its importance to us as animals, as soon as it becomes a thing to talk about consciously it begins to change its meaning. As etymonline shows, originally used in conflation with its contact and efficacy on living muscle tissue, it had the positive sense of showing the anuimal energies in activities not usually associated with such energies like writing. It was good to feel the body that drove language especially in poetry, that’s one reason for the grotesque admiration of John Donne:

We call such poetry embodied not just because we hear a human voice articulating its rhythms – possibly the force of the rhythms as we reproduce them as internally ‘heard’, but that the language appears and feels driven by the force it borrows from the reader’s own body – force of nerve driving muscle, so that words like ‘sucked’ and ‘snorted’ get visceral realisation – especially given the cunnilingus imagined in the Elizabethan / Jacobean reading of ‘country-pleasures, we feel the force of the lips in producing these words’. It was good to write ‘nervously’, good to feel the feel of motivated sinew.

However as knowledge about the anatomical system becomes more available cross-culturally, the nervous system becomes more and more associated with the secreted (rather than merely unconscious) and with shame when it pollutes language thought to be of the mind with consciousness of the body. Nowhere more so than in the poet Tennyson, whose honouring of the ‘dark blood’ of his family made his morbid sensitivities to the world an embarrassment of functions he fears might be seen but should not be so. as he writes to the ghost of his beloved Arthur Henry Hallam to:

Be near me when my light is low,

When the blood creeps, and the nerves prick

And tingle; and the heart is sick,

And all the wheels of Being slow.

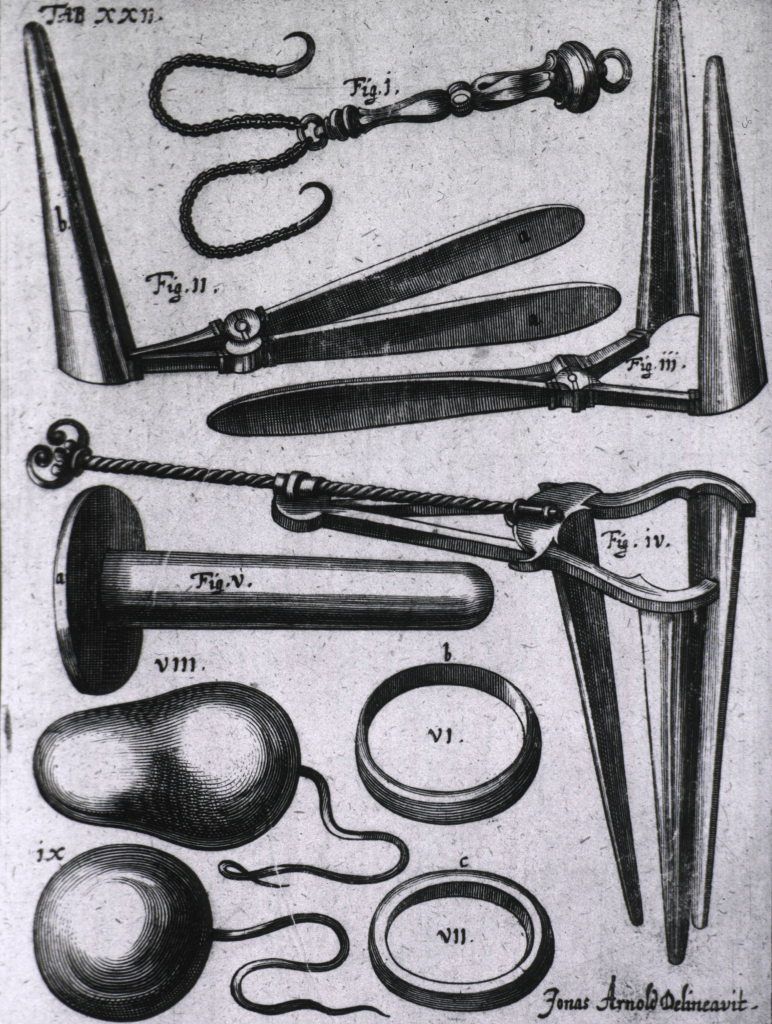

This is not just because of the stigma attached to ‘nervous conditions’ of the kind we now call depression and anxiety, but because of the fact that the nerves make the body too conscious to us, whether in misery or pleasure. They thence become secreted ans shameful – at worst irrational and wild, at best a ‘sickness’. Normal sexual excitation, especially in women, related to autonomic nervous system function became medicalised, especially in women – hysteria being an over excitation of the womb by the nervous system in their thinking and explaining the involuntary body arching of ‘hysterical women’ but also in treatments given to young men for involuntary ejaculation. Of women: ‘One 1913 article claimed that, “An intimate relationship between the female genital organs and the nervous system has been recognized from the earliest times.” This relationship, the author argued, was due to “the important influence which the function of menstruation has on the general organism of a woman.”’ (https://www.genderscilab.org/blog/new-from-gsl-a-history-of-sex-gender-and-medical-expertise-in-the-new-england-journal-of-medicine). Machines galore tended to the physical problems of a nervously over-excited body.

To ask me then, ‘what makes me nervous’, is to ask too much for the word no longer has common currency. Even here it will be answered by mentioning stimuli to the nerves, by which is meant most usually fears, like horror films or thinking of or seeing spiders or snakes. the odd person might still talk about being nervously toned after gym exercise. But no-one can answer it straight really.

The last person to answer it brilliantly was Keats, where fears are ‘nerves’ in one sense but in another are the energies of an embodied brain driving the hand to write or imitate in dance some vast motion of the cosmos. And the poem is about the real end of ALL nervous excitation – death, or the ‘nothingness’ that follows on no longer feeling our joys in the effect of nerves on and in the body.

When I have fears that I may cease to be

Before my pen has gleaned my teeming brain,

Before high-pilèd books, in charactery,

Hold like rich garners the full ripened grain;

When I behold, upon the night’s starred face,

Huge cloudy symbols of a high romance,

And think that I may never live to trace

Their shadows with the magic hand of chance;

And when I feel, fair creature of an hour,

That I shall never look upon thee more,

Never have relish in the faery power

Of unreflecting love—then on the shore

Of the wide world I stand alone, and think

Till love and fame to nothingness do sink.

When did I last feel nervous? Literally, when I read that poem.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx