As I work through my library, some books that startled me when I bought them have startled me again, for I have forgotten how novel they seemed. Such a one is that catalogue from an exhibition in the Newcastle Polytechnic in 1980 and related to the Newcastle Festival. The book was published in 1984. Organised together with the state galleries of Norway, this exhibition must have moved many minds to reconstruct Munch as an artist.

It had that effect on me when I first found this remarkable little paperback catalogue, as I saw in Munch something different from the naked and raw psychological expression stereotype that I had of Munch. But long buried on a shelf, the stereotype had returned enough for me to be shocked out of my prejudices again. This Munch is the one actively and aggressively militant against the distortions of life (psychosexual and otherwise) he associated with the bourgeoisie. In these paintings, drawings, and watercolours and gouaches, he is finding common cause with the working class and directly with the process of work, where internal psychology serves an aim, a communal one.

I have picked out two drawings originally intended as studies for fresco work painted hugely on the walls of the civic architecture they represented in the building thereof. The first is a remarkable picture in the spareness of the watercolour marks but also in the firegrounding of the large bum of a worker bending as he works.

It recalls other works from the volume for Munch was fascinated by seeing work done in the snow of the Oslo terrain and seems to employ the blank paper sometimes as setting for this. But here the snow is conflated with tne white glare on it of midday sun, It is by virtue of this that he uses the tonal blues not only to set off cleared road space from tne still heaped snow into which workers dig, but also to distinguish light and shadow. Hence, the beauty, and I can think of no other word of it of tne art that captures the foregrounded worker’s slack arse, shining in the sun, possibly as blank paper delineate in blue and tonally shaded in a other blue. I have never seen an object so elevated by art, I think, from a low base.

Looked at in detail, the marks of paint seem roughly delineated. The effect is created by the simplest of marks and their interactive overlap – somewhat like the way Rembrandt uses cross-hatching. there is a subtlety of colour nevertheless – emergent pinks and reads which add to the beauty of the design. It is simple in appearance but it is, when examined closely, complex in its process of creating emergent images. What it certainly is is worked at – as if the labour of the workers were analogous to that of the painter.

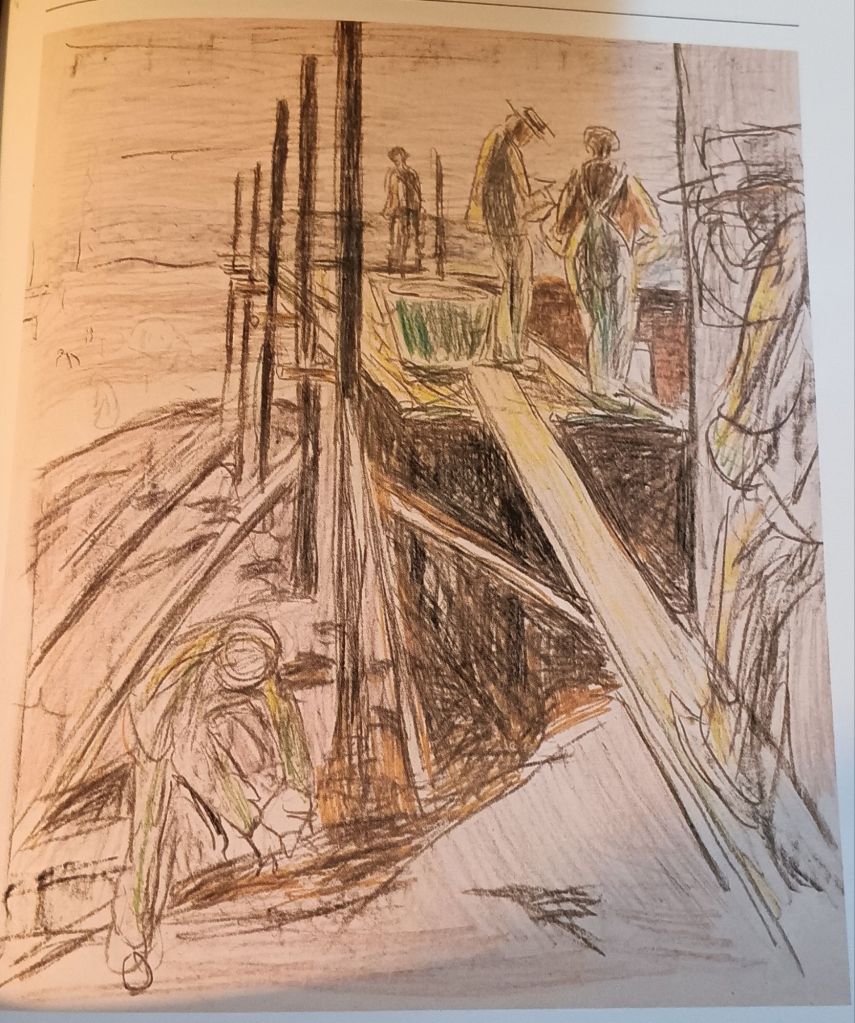

Let’s look at an even more wondrous piece, for here the construction of the page design is very clearly made analogous to the architectural structure being created, although there is some sense here primarily of the precarity of labour – the depths it hovers over and the danger of non-completion, which are forever present. See the whole picture below:

The incomplete structure is being at this time shored up by wooden buttressing stakes, making the bottom half of the picture, a criss-cross of diagonal shapes, whose volume is suggested by what appears to be pencil hatching. The upright props are lined perspectivally, the one nearest to the picture reaching right to the picture frame top and holding it up, as it were, although in perspective others are seen, as they are intended to be, as unfinished props awaiting further work before they become filled up with weight-bearing structures. At their base, the work of a worker on the ground seems to destabilise the drawn rigour of the first prop so that the lines that construct it seem to wobble. This is part of what I mean by the precarity of constructive labour and creation from raw material – whether wood or graphite and watercolour.

The space underneath that structure is dark – almost infernally and made to seem the more because of the unfinished nature of the cross-hatching that emerges as a positive presence of dark – ‘darkness visible if you like:

The very emblem of precarity is not a piece of wood that will contribute to the finished architecture but a beam plank being used for transit of labourers and materials across to the first floor constructed alrerady, At the loose ens of that plank or beam, slightly elevated by pressure on the plank caused by a workman beginning to cross it, are architect, showing plans of the building to the foreman of the works. Both have their nbacks to the man beginning to cross the blank, whose point of view we half-share. There is a sense of pressure created in the planks already laid on the first floor of the building indicated by webs of loose pencil hatching. Suddenly we are aware that the darkness beneath that floor and the plank represents the danger of falling.

This is emphasised because the foreman too stands perilously near the edge of the first floor as laid thus far, but is over concentrated in the fluid unfinished pencil, and perhaps charcoal, marks that consatitute the workman crossing the plabk. he is almost nearly not a human figure at atll but for the gross indication of his hand and head. There is a sense of overactive motion in this man, which together with the yellow staining at the boundaries of his drawn body makes him feel insubstantial or preoccupied with inner motions of thought. All this is precarious. it is precartity itself.

You can’t leave the picture without considering the ground that should hold up the structure under process of building. It is created by smears of light charcoal making it seemed striped vy uneven gaps of white that have no substance, and when substance appears it is of marks that look like holes or cracks in the ground – webs of cross-hatching that is precarity in symbol. A bit like that lieder from Tennyson’s Maud:

And ‘precarity in symbol’ That is a bit like that lieder from Tennyson’s Maud:

1.

O let the solid ground

Not fail beneath my feet

Before my life has found

What some have found so sweet;

Then let come what come may,

What matter if I go mad,

I shall have had my day.

2.

Let the sweet heavens endure,

Not close and darken above me

Before I am quite quite sure

That there is one to love me;

Then let come what come may

To a life that has been so sad,

I shall have had my day.

However, the speaker in that poem is the son of a failed entrepreneur, a father who who has hanged himself in a hollow in the wood. In Munch’s work above, our disordered male, all lops of complex hope and dismay, is in transit to safe ground we hope, though working life remains precarious for all. There is a sense that community can be built here, like the Civic Hall that is being constructed in Oslo, and one whose goal is not merely the accumulation of wealth and the repression of life forces, as in Munch’s idea (and mine) of self-boundaried bourgeois life.

Enough for today. But I am so glad I refound this book. Next to it was one from an exhibition at Newcastle Polytechnic too on Munch and photography. What might IT contain, or – fail to contain!

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx