I need to answer this obliquely in order to avoid any validation of the notion of unique personalities. They do not and cannot exist. The argument might be worth taking up another day but my aim today is to assume that we should and must avoid the tendency in single-issue thinking to invoke moral panic. As the rather good Wikipedia page describes (see the last link to read it) moral panic, it is a a tendency to oversimplify a sense of malaise about the current condition of a community (or state or the globe) by focusing on a single-issue enemy: the kind of feverish action that generated witch-trials at various points in time and space, and deflected from real issues. James I was a master of this mode of thinking and turned into into a kind of moral polics – the subject of the wonderful novel by Jenni Fagan named Hex.

Witch-hunting is a historical example of mass behavior potentially fueled by moral panic. 1555 German print (Wikipedia page cited above)

Let’s take an example though very much about today – the moral panic over the fate of adolescent boys and the search for demons. Andrew Tate is an obvious an example of a straw men in this case: obnoxious and brash father-substitutes for what Gareth Southgate , in a well publicised ‘lecture’ rationalising moral panic recently given ritual coverage on TV in the mainstream media, called a whole generation of ‘fatherless boys’ are now seen as the straw men they are and as a symptom of the over-influence of social media in the absence (or so its claimed) of an effective patriarchal family structure, governed by effective fathers. It is the chicken-and-the egg situation for the stokers of moral panic. Rootless boys create the vacancy that is the absence of fathers, physically or morally – absent in person or in effectiveness as patriarchs – in contemporary culture.

I have recently watched the 4-part TV series Adolescence streamed on Netflix.I thought it a frightening picture of both the malaise that currently characterise a drifting society, continually looking for one-issue redeemers (be it a political party or regeneration of leadership thought of as the birthright of strong fatherhood principles). Adolescence is not I think a symptom of that moral panic, though its best episode (Episode 2) shows a father (Ashley Walters as DI Luke Bascombe, the police Detective Inspector responsible for the arrest of the 13 year-old Jamie Miller (played brilliantly by Owen Cooper) at the series’ centre trying to redress the failures of modern schooling, and possibly the modern family as he sees it, by taking time out at work to bond with his own son . T

his was as much, as far as I was concerned , a moment of despair – however morally and sentimentally beautiful – as much of the rest of the series of hopeless reactions by masculine ‘authority’ to a wider and much more nuanced problem, highlighted by this brilliant drama. Wikipedia outlines the premise of its plot thus:

In an English town, police break down the door of a family home and arrest Jamie Miller, a 13-year-old boy, on suspicion of murder of a classmate, Katie Leonard. Jamie is held at a police station for questioning, and then remanded in custody at a Secure Training Centre. Investigations at Jamie’s school, and questioning by a forensic psychologist, reveal that Jamie has been deeply disturbed by school bullying via social media centred on incel subculture.[1]

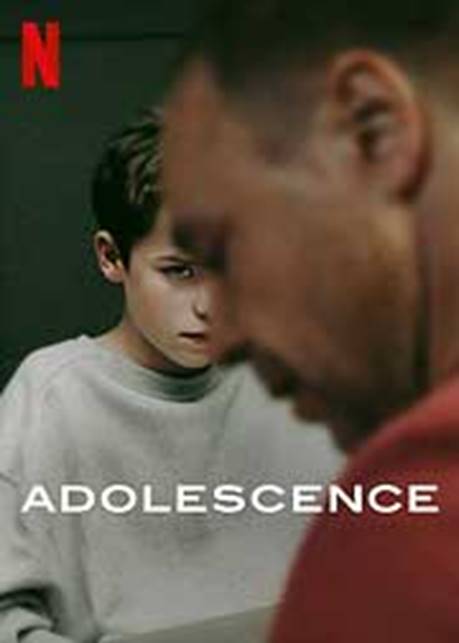

That plotline could be used to double down on social media as the problem exposed by the series, but it might miss the vital role of a the exploration of the blame allotted by moral panic to supposedly ‘weak’, non -punitive fatherhood as brilliantly played by the stupendous actor, Stephen Graham as Eddie Miller. We need to look later at fatherhood in the plot, for even the Netflix poster for the event, by some clever blurring of the father in the foreground, emphasises this issue:

To that we will turn. Nevertheless we need to confront the fact that Adolescence is being used to fuel the next round of moral panic about adolescent boys, or in Gareth Southgate’s version ‘fatherless boys’. I do not think that was its aim, and we need all the uniqueness we can muster to contest it. But first let’s look at evidence for the panic. I would take. Yesterday’s The Observer carried an article by Martha Gill entitled ‘Adolescence reveals a terrifying truth: smartphones are poison for boys’ minds‘. The simplifications and toxic diction here – for what is more poisonous a word than ‘poisonous’ – are the first signs of moral panic and render less than meaningful the obligatorey praise fgiven to the show’s cast, and notably to Owen Cooper, whom they picture in a moment of supreme apparent innocence (which is not at all what fixates in the drama when seen):

Owen Cooper as 13-year-old Jamie Miller in the Netflix drama Adolescence. Photograph: Netflix© Photograph: Netflix

Gill is certain that Adolescence is a one-issue how. she even compares it to ‘Mr Bates vs The Post Office, in which the plight of subpostmasters was rendered with such success that it actually hastened in real-world legislation to compensate them’. [1] Her article then outlines two answers to the dilemma – aligning herself with Gareth Southgate as she does so, whilst keeping to a different line in her ideal answer to the same problem – where Southgate wants more state funding for youth and sports centres for males in particular, Gill wants to control access to smartphones in young men. She describe’s Southgate’s position thus: ‘that the problem stems from an unfulfilled need among these young men – a lack of guidance, or self-esteem or of other men on which to model themselves’. gill continues:

That was the central contention of Gareth Southgate’s Dimbleby lecture last week. He talked of an “epidemic of fatherlessness” and the fact that boys are spending less time at youth centres and sports events where they might have met the kinds of aspirational figures Southgate looked up to: coaches, youth workers and teachers. Without this, he said, boys are driven on to the internet “searching for direction”, where they stumble on role models who “do not have their best interests at heart”.

Gill, on ther hand thinks state provision of this kind a mistake for:

online culture is not merely compensating for the real world, but outcompeting it. As tech geniuses devote all their brainpower to keeping people engaged, algorithms are getting smarter, and online life more exciting. … These platforms take the stimulus to socialise – recognition, inclusion, approval – and gamify it to an addictive level. Why spend time with your friends or go to community centres when online culture is more rewarding?

Her conclusdions ask for direct action of government but not for state provision and funding but authoritive regulation:

Is it time for the government to restrict teenage access to social media? A bill that campaigners hoped would ban addictive smartphone algorithms aimed at young teenagers was watered down earlier this month; that may have been a mistake. France, Norway and Australia are experimenting with smartphone and social media bans for children and teenagers. It may be time for us to do the same.

That is the kind of pretend hesitancy about censorship or ‘killing off’ measures that fuel moral panic, not least because they are entirely unfeasible. Government regulatory power too is mow secondary to the power of the great tech companies – and not only in trump’s USA. Again I SHOULD tackle this argument fully but it is yet another too-large topic.

My less urgent concern is the awful simplification of great modern drama by such moral panic interpretations. if you want to try and be unique, look for the amazing brilliance of the fusion of issues in the drama Adolescence, down not only to its fuel for analysis of the absolute failure of schooling, and civil society to support parenthood. The final episode of the series was brilliant because it deflected from seeing the problem as about ‘masculinity’ (whether toxic or ‘weak’) to showing that parental love is undervalued and under-supported in preference for ‘hard’ measures – the sure sign of patriarchy. When Tony Graham tucks his son’s teddy bear in bed in lieu of being able to do so for his son, the effect is not only to jerk tears (though it does) but to show the absolute fear of the terrain in which we expect parents to operate – taking on all the responsibilities the state has abandoned in favour of process models of ‘excellence’ in schools, youth justice and surveillance in civil society (the role of CCTV is focused in this drama). No longer dor schools promote and en engage with the values of youth but merely regulate them. Civic and Humane education has been flushed down the pan and instead the culture of ‘go-getting’ and success at all costs is becoming prominent. Good teachers buckle under this kind of culture – bad ones rise and strengthen the system into even more mechanical rigidity.

There are no simple answers. We need not a focus on the tackling adolescent male models of authority as a reconfiguration of answers that think this is all to do with sex/gender. Tackling misogyny can only be done by resdistributing power and responsibility without doing so in gendered ways first (either covertly as partiarchy as long done or overtly as binary radical feminism does today). We need a new civic model that stresses responsibility across sex/gender as across species, one that founds itself on communalism not competitive individualism. the chances of that currently are poor. Governments of our time (even the British Labour government) see change as led solely by economic growth and deregulation. regulation isn’t the answer but it can be used to prompt civic responsibility that respects diversity and inclusion.

But meanwhile see Adolescence. Whilst he male roles have taken most kudos, often for good reasons, look out for Christine Tremarco as Manda Miller. This is a performance of the first order and an argument for the kind of stoic resistance to moral panic and over-simplification should start with what this character has to say and how she enacts her responsibilities, without recourse to over-easy answers:

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

________________________________

One thought on “In truth no-one is ‘unique’. The best thing we can do is to avoid turning to the single issues that fuel ‘moral panic’.”