When Adam in Book VIII of Milton’s Paradise Lost gets the chance to quiz the Archangel Raphael (man to man, as it were) he has one thing on his mind. He wants to know how to sort out the confusion he has about the satisfaction he feels as a result of loving Eve, created for him by God. He insists it is not only because of the joys opf the ‘genial Bed’ that transports him but the daily commerce between them and the exchange of looks and carnal touch. All this is ‘love’.

He desperately wants to know if an angel can even understand the mix of things that make a human Adam feel he knows what elements make him know that he loves Eve. But he wonders if he might upset the angel with his possibly impertinent, or perhaps ‘unlawful’ question, and so he starts by reflecting back to Raphael his praise of the role of love in lives – angelic or otherwise, and then asking the angel to ‘bear with’ his need to know more. After all what he needs to know is whether Angels feel love as he does – and though he knows it a moral and spiritual quality does it also include the sense that, of necessity, implies bodies – one that acts to touch and one that feels that touch:

To Love thou blam'st me not, for love thou saist

Leads up to Heav'n, is both the way and guide;

Bear with me then, if lawful what I ask;

Love not the heav'nly Spirits, and how thir Love [ 615 ]

Express they, by looks onely, or do they mix

Irradiance, virtual or immediate touch?

Only Milton could end a line with touch thus, so that it sparkles outside of its frame, with suggestion and association. And that sparkling is not lost on Raphael. Raphael’s’ blush is the most human thing in the poem – a mix of embarrassment and recognition in that he knows what Adam is talking about, but also has picked up on something else in Adam’s discourse – not only is he quizzing whether spiritual beings can ‘touch’ each other but whether they should touch each other, when that act of touching has no heteronormative or ritual framework to justify it, including the motive of child generation that makes a bed ‘Genial’. The word ‘genial’ after all already implied the sexual act as condoned in marriage, as etymonline.com shows us:

1560s, “pertaining to marriage,” from Latin genialis “pleasant, festive,” originally “pertaining to marriage rites,” from genius “guardian spirit,” with here perhaps a special sense of “tutelary deity of a married couple,” from PIE *gen(e)-yo-, from root *gene- “give birth, beget,” with derivatives referring to procreation and familial and tribal groups.

No wonder Adam is embarrassed. Of course, he needn’t be – even the genesis of sex those of differing sex/gender is a young institution, although it is note that Adam has notice that the animals too love only between the binary of male and female. They don’t, of course, but we can’t expect Adam to have read about animal sexuality. The only angels he sees all look male and have male names. So to ask whether they touch each other is a high risk strategy (ignore by the way those who think Milton could not know about queer sexual relationships or was too holy (and too early in history. He most certainly did. Raphael’s blush makes it certain that angels too are capable of feeling shame when lesser beings question their unisexual nature – claiming that they blush only because of what these lesser beings think about the truth of their celestial couplings:

To whom the Angel with a smile that glow'd

Celestial rosie red, Loves proper hue,

Answer'd. Let it suffice thee that thou know'st [ 620 ]

Us happie, and without Love no happiness.

Whatever pure thou in the body enjoy'st

(And pure thou wert created) we enjoy

In eminence, and obstacle find none

Of membrane, joynt, or limb, exclusive barrs: [ 625 ]

Easier then Air with Air, if Spirits embrace,

Total they mix, Union of Pure with Pure

Desiring; nor restrain'd conveyance need

As Flesh to mix with Flesh, or Soul with Soul.

But I can now no more; the parting Sun [ 630 ]

Beyond the Earths green Cape and verdant Isles

Hesperean sets, my Signal to depart.

The answer though is indubitably clear. Purity is a matter of context. Bodies can commingle purely in the moral sense, as Adam was struggling to say – whilst not denying the fact of embodied sex acts – but ngels commingle even more easily because they do not have to take into account the kind of visceral bodies humans were made with: ‘membrane, joynt, or limb, exclusive barrs’. That term ‘exclusive barrs’ is a gift to queer readers. it explains why that, though men and women have a biological difference that remover bars to the penetration of one body into another, angels don’t need that difference. In a sense, the answer insists that you must not think about how male human beings might have ‘mix, Union of … Desiring’ like the apparently male to human eyes angels.

On the net, you will find all kinds of abuse of modern academics for finding anything ‘geh’ in all this. Take the page from Reddit at this link. But this is not a matter of academic degeneracy as these commentators think, but of understanding the joint role of the pursuit of three things in love at the same time by beings who are embodied (like humans and other animals) or who look as if they are – like the appearance of the angels to Adam and Eve. These three things are reproductive function, pleasure and some otherness of meaning we call spiritual or ideal, rather than bodily. These are same things Milton struggled with in thinking of the meaning and justice or otherwise) of divorce in his bold pamphlet on it. And Milton left out of the issue of angelic mixing the idea of enduring fidelity only to each other within self-selected couples: ‘if Spirits embrace, / Total they mix’. There is no prohibition on with whom angel may mix.

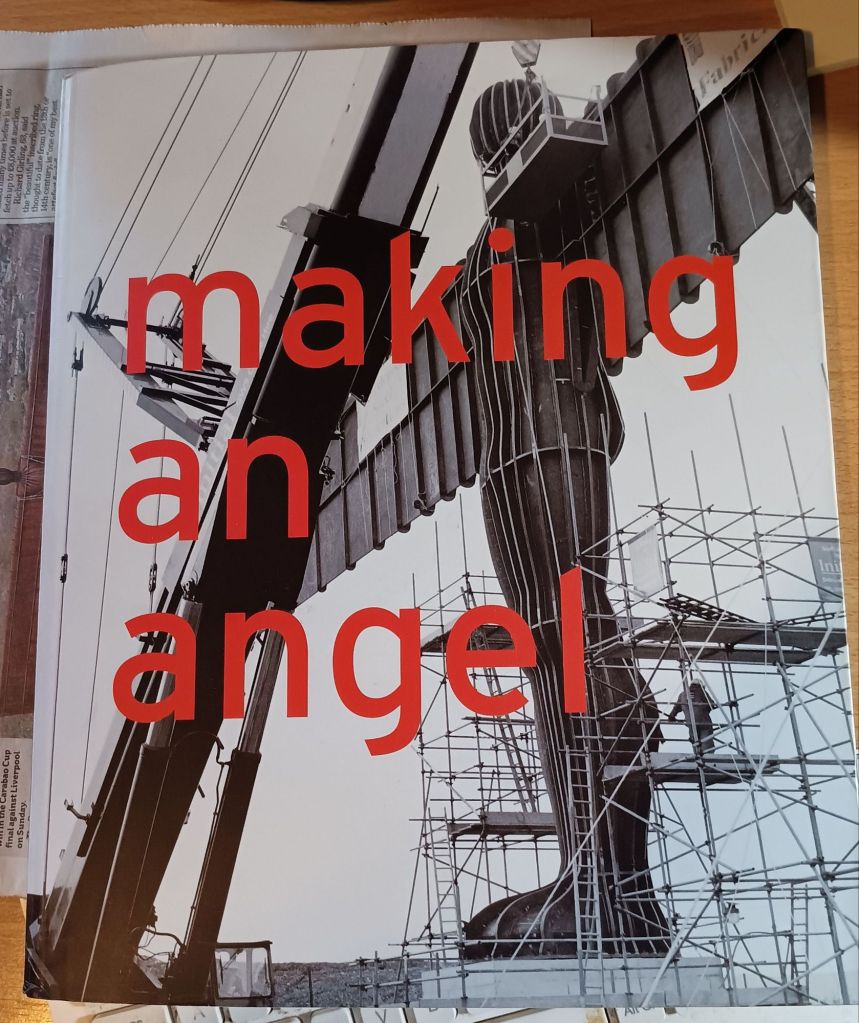

My aim in introducing this is mainly to think about why we construct, deconstruct and reconstruct the notion of angels in our everyday lives and because, in today’s i newspaper, and possibly others is a picture that shows a recent reconstruction of Anthony Gormley’s The Angel of the North in Gateshead alongside the A! as it curls around the dual cities of Gateshead and Newcastle, near my own home, by the Toon Army, the fun name of Newcastle Town (‘Toon’ up here) supporters. The Angel has been made a Newcastle supporter and their delight in the Toon is no doubt the celestial equivalent of a Toon army member’s more earthy passion in the football ground on the success achieved by their ‘team’. The dual flag in which the Angel has been dressed has back and front , has on its back, like any supporter shirt: “Tell me Ma” (tell my mother).

Picture and text from the i newspaper 18/03/2025, page 23

Milton does something similar with Raphael. He constructs his Angel so that we understand them entirely in terms of human emotions – emotions that are neither sexed no gendered because angels no such binary, even if they tend to think that that means (to human understanding just as in human understanding of God as a Father) they are all male. We need to reconstruct our ideals in ways that use the raw materials of our own less than ideal and very visceral passions (have you ever seen the Newcastle ground emptying after a match?).

As I smiled to myself at that I remembered the whole project of the placing of Gormley’s Angel, even back to its commission by Gateshead Council. At the time I was running groups for unpaid carers In Consett and Stanley. the consensus in these groups reflected the local newspaper riot of disapproval with phrases like it ‘being a waste of money’,a use of funds better used in the NHS or in helping charity projects. Yet now it is hard to find anyone who dislikes the piece and does not see it as ‘ours’or mourns the colliery bathhouse that used to be on that ground. The writer and psycho-geographer, Ian Sinclair, has noted that local people now see the Angel ‘as part of the landscape, as if it had always been there and they had never previously noticed it’. Suddenly even the locals in Consett and Stanley realised that the funds used to raise the Angel were minimal compared to, as Sinclair elegantly puts it, funding for ‘urban set-dressing to disguise the pitiful condition of the schools and hospitals’. (1)

But there is something in this fixed and static body, so tied to the earth by boots so heavy no wing span could lift it that speaks, with all its raw materials of pre-weathered iron and markers of the engineering, steel works and mining industries of the north that breaks free from those raw materials but not to become an ideal but a description of the contradictions of the industrial North, the end of heavy male-dominated industry and a new potential for freedom from sex-gender based binary structures of power. I will eventually cite Sinclair’s beautiful description of that effect in his descriptions of the thing, so full of its light and shadows. For him it is: ‘A golem released from the darkness of the body; a grounded angel denied the possibility of flight’. Later we see it is neither air nor earth, heavy or light nor male nor female but something emergent, bearing scars of the past, not seeking transcendence bu wanting to honour the place from which it springs. No doubt when I quote this – a photograph of a passage, you may say,, as you think locals might,: ‘well that’s what happens to local lads become who abscond to the South and become sissies’, but another voice is quoted by Councillor White of the Council – a local one, who shows how emergence of the novel occurs in art. She was a lady ‘from Tynemouth, Joyce Hall, who wrote to the council in January 1995 thus, but stayed with the project to its fruition, seeing it first grandly realised when she was 80 years of age. (2)

In fact the Angel is a Colossus of roads. It bridges them to no purpose. People pass it by. But Joyce voices ideas elsewhere in this paragraph that Sinclair makes more obviously recondite in his piece. Here it is. (3) His reference to a ‘great hermaphroditic presence’ is no more fanciful than Joyce Hall’s musings on sex / gender – but they are musings intrinsic to the area as one culture dies out and others struggle to be born, but are not complete yet:

When we commission art or discuss we participate in its construction – this is true of Milton and Anthony Gormley, but artists don’t make art out of nothing – they make it out of the swill of ideas in their time. They create the mess that survives – something contradictory, but it is only in reconstructing the art work again in this swill of raw talk about bodies that we will make something significant that doesn’t depend on fanciful ideas of divine transcendence.

I will leave it there.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

_________________________________________

(1) Iain Sinclair (1998:27) ‘achieved anonymity’ in Gateshead Council making and angel London, Booth-Cliborn Editions, pages 26 – 39.

(2) cited Mike White (1998: 21) ‘a northern tale’ in Gateshead Council op.cit: 20 – 23

93) Iain Sinclair op. cit: 29