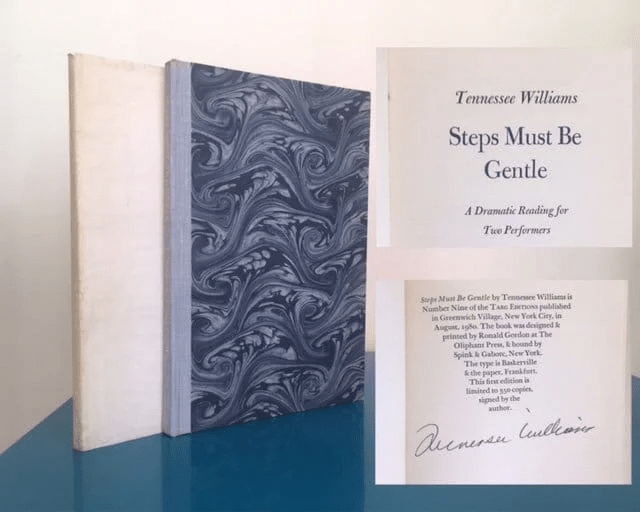

A collage of features of the first play mentioned below, This is not my copy though it is identical and has the signature

As I clear my bookshelves, cataloguing what I keep and dispensing the rest to fate, I occasionally start reading them. My collection of Tennessee Williams’ work is though sacrosanct and none will be moved on. It is not complete but is full enough but it is not, and this is unusual, all made up of things I have read as yet. So today I sat down to two very late plays. The first, a one-act piece named by him ‘A Dramatic Reading for Two Performers’ is based on a posthumous and indirect conversation between Hart Crane, the great queer American poet who committed suicide by self-drowning, and his mother Grace, in which the latter appears as both a kind of muse for the poet’s talent and opportunity to develop it and a bind on his development of an independent and self-sustaining sexual being. Grace would give Hart anything, or at least say: Name me something which I didn’t allow you, …’. What she did not allow Hart or allow to be value so that even the ghost of Hart blames her ghost (Williams called many of his late plays’ghost-conversations’) cannot be named or valued so that Hart himself, now dead, sees as his parents pre-disposition of him towards ‘wayward kinds of love-seeking’. That ‘love-seeking is anathema to Grace. She names where Hart can find no words:

the, the – sex of sailors picked up in Brooklyn, dock-side bars as if they were thin bits of bread that symbolized Christ’s flesh at Holy Communion, and their seed as it were – His blood!

There are a some deep associations here between sex as substitutive of spiritual worth and its celebration, the need to eat ‘the bread’ that sustains life and what is forbidden and not to be named but in disgust.

Edward Burra’s sailors recall those in these plays

Why does Williams make Hart blame hie his parents for his queer sexuality? Why does he associate it with the fact that they encouraged his art but only at the cost of a life lived as others live it? In life Grace gave him, in order that he could do his creative work, a thoroughly isolated place that she describes as ‘the tower room of the house, phonograph playing all night as your fists pounded out the cadences of your verse’. It was this conditional life (an isolated one) that turns Hart – and by implication Tennessee Williams configuring Hart’s family drama into a ghost-play – ‘toward … wayward kinds of love-seeking’.Hart blames his parents for making him ‘beg’ to ‘own’ for myself any of the basic things in life that weren’t turned into little ‘remittances, pittances, tight-fisted little dribbling of doles on which I had somehow to subsist’.

And there is in theses strange psycho-social connections between the need for an income on which to live, large expectations of a loving regard that made him feel worthy that fastened themselves too soon in Tennessee to an explanation of his queerness. For to be queer in Williams (even queer like Blanche), even in the great early plays is always a problem despite the fact that Williams in life lived for and in queer desire quite openly at least amongst his social, literary and theatre set, though often at loggerheads with them for their basic failures to ‘understand’ (and love enough) him and his plays. Hence, in Steps Must be Gentle stage directions call for audio-scapes that down out the words exchanged between persons, such as this wonderful example:

WIND AND SEA SOUND, vast and heavy, subside before words resume.

The danger that noise will arise from the Unconscious is presented as if from the sea in these early plays – through the sea matters to The Glass Menagerie, and not just as a place where you pick up sailors available for sex to anyone. There is such a sailor in the posthumously published play, Something Cloudy, Something Clear which I read for the first time today, who variously throughout the play sexually services the character enacting Williams, know as August (pronounce it as if French), vomits on his beach-shacks floor and talks practically and pragmatically about sexual need and variations of male sexual capacity, especially combined with drink. The Sailor is as frank about sex whether experienced as need or a commodity to be sold directly or indirectly (for a place to stay overnight or for alcoholic drinks in dock bars. But August too is constantly worrying that he too, ever ready to find ways of hiring sex, with the character Kip for instance who like his asexual (to him) girlfriend, Clare. Both are looking for a man to ‘keep’ them, yet Kip is as sure that he is not ruling out, but equally sure he is not ready yet, to sleep in the same bed as August. No-one directly relates all this sex as part of a transaction ( what Kip calls the ‘exigencies of desperation”) but everyone is sure that there is something not quite right or is ‘cloudy’ about it, however ‘clearly’ negotiated it is.

The thing is August (and Williams) believe they do the same with their creative work – are forced to sell it to audiences that cannot understand it and vis a machinery of theatre-craft that equally does not. Yet if a writer is to live he must sell his creative spirit, leveling it to the level of theatre producers and directors and stars of the theatre – many appear in ghostly form in this platy with pseudonyms – the ‘Fiddlers’ as theatre directors, Caroline Wales (representing Armina Marshall) or directly named like Talulah Bankhead, his first girfriend, Hazel, and his life-partner – a ghost on stage but now dead, the real lover of Williams, Frank Merlo. Amidst all this cloudy mess nothing is entirely clear – the play gets its name from August’s (and tennessee’s) cataract in one eye which makes thing both cloudy and clear in double-exposure. And as in the play about Hart Crane, the stage directions give voice often to the sea that edges the beach on which the story is enacted: the ‘sea booms’ when words get too near to Tennessee’s very double understanding of his and August’s sexual nature and its links in real life in his ability to buy people, with his huge wealth by then, like The Fiddlers but his plays and change them into what they want not what his creative spirit requires. This is exactly how Williams saw the treatment of his plays when turned into films by powerful film directors who knew what sold and, in his view killed Cat on A Hot Tin Roof, by resolving the relationship between queer Brick and Maggie the Cat.

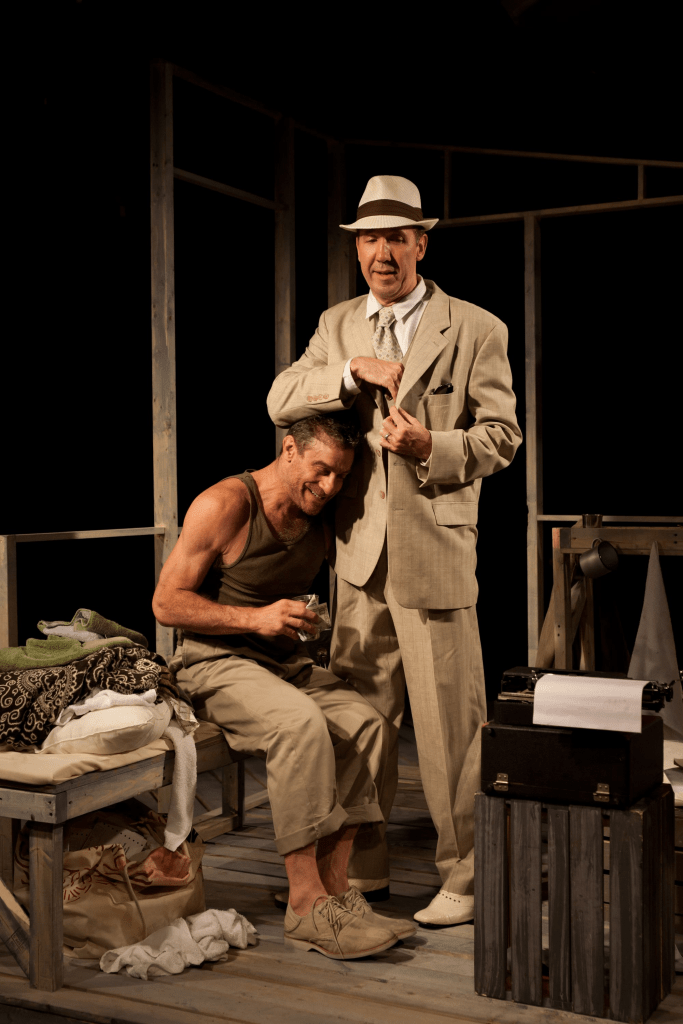

The 1995 first edition book of Something Cloudy, Something Clear contains an introduction by Eve Adamson who directed the play for Williams at the Jean Cocteau theatre. She hints at the depth of the play’s unresolved issues around queer sexuality but they are also about being drowned out by the sea, which in the mise en scene must sit where the audience sits and takes part in corrupting the playwright with a taste for money rather than creative satisfaction. Maurice Fiddler – the producer in the play, says, speaking suddenly of the young August not the jaded money-stuffed character that he can equally be in his older age (the ‘cloudy’ now not the ‘clear’:

Tennessee Williams (1995: 41) Something Cloudy, Something Clear New York, New Directions.

Tennessee Williams could never forgive himself, or his parents that he was queer, for his sister’s poor mental health or thathe might have lost everything from his creative life except the ‘taste for booze’. How please I am to have the books to read and re-read. whatever, the issues – they must compel – they are rooted in a real life, the same as many now live (though we try to be clear not cloudy.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx