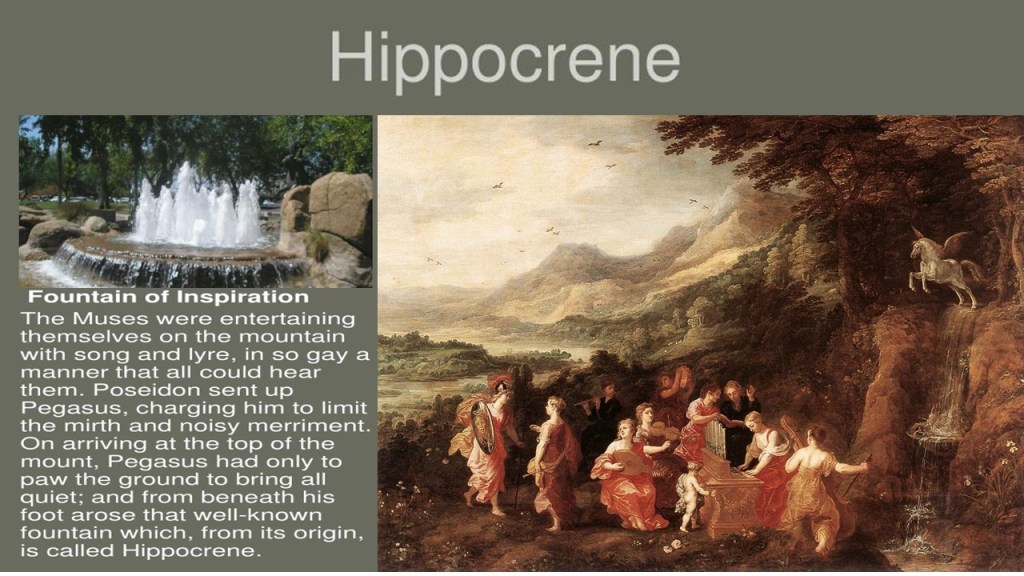

Hippocrene source on Mount Helicon By GOFAS – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11613794

Like everyone else I fancy a sip of the Hippocrene. Above is a photograph claiming to be the real source of the river on Mount Helicon, long famed in mythology as the haunt of the Muses – those nymphs responsible for the arts. Take one sip and some expression of some art just flows flows from you – joyous and unregulated (what people tend to call ‘inspiration’ – where a divine breath has breathed into you for some realm above is breathed out again, or at least so we think. In fact the best versions of the myth I have come across shows that the fountain is not so free an idea as my last sentence seems to suggest it might be. The origin of the fountain, spring or waterfall (it is variously represented) absorbed Hendrick van Balen or Hendrick van Balen I (c. 1573–1575 – 17 July 1632) enough to use it on one of his miniatures scenes etched onto a cabinet that I use below:

The picture needs the nuance of the explanation, taken from a slide (presumably used for some educational purpose) I found also on the wanton internet. Take note: the holy horse, Pegasus (Hippo in Greek being a horse) is sent to the Muses not to free their song and let it rip but to ‘rein’ it in. Inspiration is not for hoi polloi (the people), it is holy and must be used with respect to that fact and reserved for those Milton called ‘fit audience though few’. Pegasus render the muses quiet at the same time that he shows them that inspiration flows down a measured course, coming from a hierarchy in heaven not the masses at play in the valleys.

In literature ever since drink has been double-edged. At the one level it frees up unreserved pleasure and in the other is merely a false thing that dulls human pain. Especially as alcohol (the Bacchic or Dionysiac gift) it either heightens pleasure or dulls pain. Shakespeare as Iago in Othello Act 3 Scene 3, has that great user of alcohol to incite riot, invoke a stronger substance than alcohol to show how some pains might not be dulled as one hoped. He vows to make his commander so jealous (using fanciful ‘evidence’ of his wife’s infidelity) that:

Not poppy, nor mandragora,

Nor all the drowsy syrups of the world,

Shall ever medicine thee to that sweet sleep

Which thou owedst yesterday.

We might think of those wonderful lines when we look at how John Keats invoked his ‘favourite drink’ (so to speak) in his Ode To A Nightingale by the name ‘Hippocrene’, clearly associated here not with water but the wine offered by Dionysus / Bacchus. Nevertheless, Keats is aware that his requirement, even for a ‘draught of vintage’ has behind it the opiates that Iago evokes as a a wish for ‘drowsy numbness’ that might never again benefit Othello. And not just opiates to numb but a more toxic drink yet – the ‘hemlock’ Socrates drank in accepting his death sentence from the powers that were in Greek democracy. Keats incomparable verse enacts and performs the servuces of the drinks he mentions – dulling and enlivening the senses both.

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:

'....

O, for a draught of vintage! that hath been

Cool'd a long age in the deep-delved earth,

Tasting of Flora and the country green,

Dance, and Provençal song, and sunburnt mirth!

O for a beaker full of the warm South,

Full of the true, the blushful Hippocrene,

With beaded bubbles winking at the brim,

And purple-stained mouth;

That I might drink, and leave the world unseen,

And with thee fade away into the forest dim:

However that Bacchic Hippocrene – with its wine-stained mouth recalling the wonderful 1595 rent-boy turned semi-god by Caravaggio – is not so innocent as we might think. It still regulates life more than it allows that same life to flow in indulgence – we never forget that both ‘opiates’ (poppy’ to Iago) and alcohol are toxins as well as deemed to create liberated joy:

The aim is still to ‘leave the world unseen, / And with thee fade away into the forest dim’. Imaginative – yes – but deathy like ‘hemlock’ – certainly! Abandoned Muses don’t get away with much – they get stilled to quiet by the horse of God and told that all inspiration needs order. In no case more than Keats, who cannot know whether he wakes or sleeps but is certain that even imagination does not suffice to carry you away from duty to change that ‘sole self’ into something that has communal value.

Forlorn! the very word is like a bell

To toll me back from thee to my sole self!

Adieu! the fancy cannot cheat so well

As she is fam'd to do, deceiving elf.

Adieu! adieu! thy plaintive anthem fades

Past the near meadows, over the still stream,

Up the hill-side; and now 'tis buried deep

In the next valley-glades:

Was it a vision, or a waking dream?

Fled is that music:—Do I wake or sleep?

Tennyson rather enjoyed showing that it is not just lingering in the mind of the ‘sole self’ that is a drink favoured by men dissatisfied with life as it is lived following the norms expected of you. But Tennyson cleverly shows us that even an ‘active social life can be a drug, even one aimed at the good, as people of claim, of your nation. One of his cleverest ambiguities is in his poem Ulysses, wherein he summarises his career that takes Homer the whole of The Iliad to tell, thus: ‘And drunk delight of battle with my peers, / Far on the ringing plains of windy Troy’. Ambiguity, you may say- I see none! But is ‘drunk’ here the past tense of the verb ‘to drink’ or an adjective descriptive of the delight men want from war – that has made them ‘drunk as alcohol does. Tennyson never but wanted it both ways. Because he felt the pull his charachter here does in his dramatic monologue – to treat ‘life’ itself – meeting new peole , having new experiences – as a ‘drink’ – his ‘favourite drink’ – that depends not on imaginative transport on the wings of a nightingale but real travel – across continents – just to show that there must be more to life than a ‘still hearth, among these barren crags, / Match’d with an aged wife’:

Life is a drink but it is not over till the cup is drained ‘to the lees’:

I cannot rest from travel: I will drink

Life to the lees: All times I have enjoy'd

Greatly, have suffer'd greatly, both with those

That loved me, and alone, on shore, and when

Thro' scudding drifts the rainy Hyades

Vext the dim sea: I am become a name;

For always roaming with a hungry heart

Much have I seen and known; cities of men

And manners, climates, councils, governments,

Myself not least, but honour'd of them all;

And drunk delight of battle with my peers,

Far on the ringing plains of windy Troy.

Ulysses is clear that though he travel alone, his aim is to change a situation where people don’t ‘know not me’. Forgive the double negative, but here it works, I drink to be known by others. Is fame a more true ‘favourite drink’ than we admit, for even Keats knows that locked in his house in Hampstead, he will never cut the mustard. But then his poems of retired resignation are published and act silently as ambiguously loud as does Tennyson’s Ulysses.

As for me – my favourite drink – I will stick to ‘sparkling water’ with nothing blushful added.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxx