Is Macbeth truly about a man straining for greatness, or is it more accurately a ‘woman’s story at a winter’s fire’ that shows the true heights to which the masculine can aspire? This blog is on the live-streaming of Max Webster’s Macbeth starring David Tennant and Cush Jumbo.

I am always resistant when the opportunity to see Macbeth arises, with much fanfare of its ‘star’ in its wake. Even the recent appearance of Ralph Fiennes in the lead role failed to tempt me to see a production that just preceded this one in the theatre or even the live streaming of that production. I sometimes try to afford to go to London overnight for thing – my next jaunt is at the end of the month for the Old Vic’s rather critically slammed Oedipus and The Duke of York’s Theatre’ much hailed Elektra all in one day (see my anticipation in blog linked here). And, it felt the same might be the case for the Donmar Warehouse production were it not that it too has been livestreamed to packed audiences. I saw it on Sunday 9th February – its second outing in one week at the Gala Theatre in Durham, and even on a second outing could only get seats high in the circle. Stars bring out the worst in audiences. One couple to our left continually rustled their sweets to one side of us – even through the play’s most wondrous soliloquies.

Those wondrous soliloquies are the issue with this play – one that often fails it as drama where people want more visible external action than reflection upon that action. Just fail in the delivery of its tough verse or overfill the stage with action obtuse to the verse and the play dies – well at least for me. Indeed, I can only remember one production of the play, and I have seen 7 or more, that I have liked.

This prior exception was a production that I saw in the Tramway Theatre in Glasgow in which Alan Cummings played all the scripted roles in the play as if they were voices externalised from within the head of a psychiatric inmate, who had a grotesque identification with Scotland perceived as a victim of a forensic external power. The other actors had non -speaking roles as psychiatric doctors and nurses walking around the place where the character played by Cummings was detained – sometimes in an extreme physical containment including a straitjacket.

That production gripped me – though I did not understand, other than in the brilliance of Cummings, why that might be so till now. One reason is that the forensic psychiatric model appeals to a theme in the play that has never seemed so forefront to me before seeing the Donmar production. Moreover, notwithstanding the incomparable and visceral playing of the play itself as a dialectic of internalised victimhood by Cummings, I think Max Webster’s Donmar production appealed to me more as a whole and ensemble production. Tennant is a brilliant Macbeth (as he was for different reasons and with different technique a great Hamlet and Richard II, but my preference is not based on a comparison of star quality – it would seem bad to make it even – but on the fuller more internalised conception of the role in the context of the play.

There is reason to forefront psychiatry externally for a modern audience, though the Doctor of Physic in the play is a long way from having the power to subdue nobles, let alone Kings. The Donmar production too however played on the mental health edge in both its main characters and the defences against neurosis in its masculine victors. There is no better symbol of binary sex/gender roles than Noof Ousellam’s suitably actorly-stiff Macduff, who walks, talks and projects like ‘a man’ ought, with projectile sword-phallus at hand and reflected in the glass behind which mentally interior actions scenes play out – blank for him though as becomes a man true to his social construction script.

Nous Ousellam as Macduff

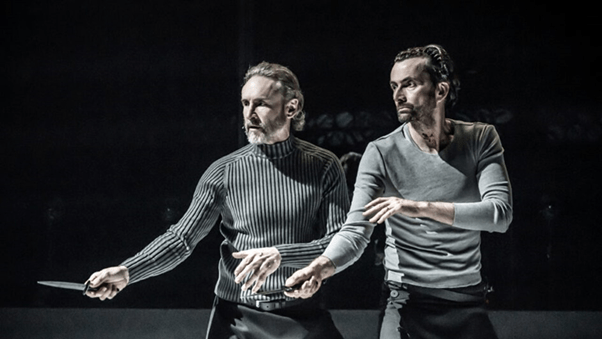

With that sword-phallus in mind for a truly military man, compare in this production the one time we see Macbeth and Banquo approach a foe in a slowed down action with the quality of dance and with small dirks only brandished.

I will return to the manly or ‘imperial theme’ later – indeed it is to my mind adjunct to what follows and this is underlined in this production of the text’s prompts to it. Let it be enough before I attempt that to cite Marianka Swain’s view in London Theatre (online) that this too, for her was a feature of the play and circled on Macduff and the excellent enactment of his stiffness by Ousellam:

This martial society’s understanding of masculinity is another interesting thread. Noof Ousellam is hugely affecting when his Macduff learns that his family has been murdered, and refuses Malcolm’s urging to “dispute it like a man” – to immediately turn grief to violent revenge. First, he declares he must “feel it as a man”.[1]

My own feeling is that we do not need to evoke a ‘martial society’ in the past to cover this theme, for the aim to ‘feel it like a man’, which is to repress its outward show still lives with us. This review, like others and I instance Time Out, gets Tennant’s actorly version of Macbeth the character wrong because they historicise it unnecessarily. Swain says (I excerpt from across the whole review below) effects in the play make the audience collude with:

David Tennant’s devious, sociopathic politician, who schemes in corners and whispers his darkest thoughts. …./ …. Rather like Tennant’s Doctor, he relishes being the smartest guy in the room, but as the bodies pile up, and he misunderstands the witches’ prophesy as immortality, he becomes a terrifying moral vacuum, a god who worships himself. / He’s a Machiavellian plotter, too, who might well have butchered his way up the career ladder even without the witches (and since we never see them, they might well just be thoughts in his head). He prostrates himself on the floor before Duncan, but, once that first slaughter is done, swiftly embraces the autocrat’s playbook: no critics, no witnesses. He even has a direct hand in child murder; Fry draws audience gasps with the unmistakeable sound of a neck snapping.

That last point was important and it relates to things we must say about children in the play (in fact it is an enactment I think of a moment similar to that of another inner dramatic monologue that makes masculinity a problematic thing to perform: Browning’s Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came. Here is Stanza XXI:

Which, while I forded,—good saints, how I feared

To set my foot upon a dead man's cheek,

Each step, or feel the spear I thrust to seek

For hollows, tangled in his hair or beard!

—It may have been a water-rat I speared,

But, ugh! it sounded like a baby's shriek.

Stephen King’s novelistic version of Browning’s poem has this image.

This is largely the view too of Andrzej Lukowski in Time Out:

What’s really interesting is that Lady M soon becomes consumed by guilt – especially once child murder comes into the equation – while Macbeth experiences almost none. One way of looking at it is that this is simply dispensing with the idea of a dithering Macbeth pushed into murder: he was a ruthless bastard from the start. Meanwhile Lady M’s humanity is bolstered by having her visit Lady MacDuff shortly before the latter’s murder, in what’s clearly a fit of conscience (she takes the lines of the minor character Ross, an idea the Almeida’s recent production also hit on).[2]

Both seem to want to make Mabeth a stereotype of the Edmund (in King Lear) politician. However Lukowski thinks there may be another way of interpreting the evidence given above. In the very next paragraph, he says:

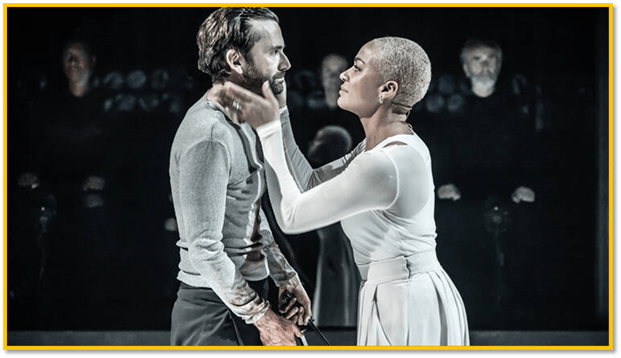

Another way to look at it is that Webster is showing the black-clad Macbeth and white-clad Lady Macbeth to be parts of the same whole, with the increasingly horrified Jumbo coming across less like Tennant’s wife, more the vestiges of his humanity. His behaviour gets more depraved as she gets iller (or vice versa – she gets sicker the worse he behaves). It’s a really fascinating idea,

I think this later insight better than Lukowski’s first, though not essentially to be interpreted as he does – for black and white contrasts are yet another cognitive binary that must yield to shade like health and illness, night and day, evil and good and woman and man. The point anyway begins to lack weight when we remember that in their latter scenes, Macbeth is dressed in grey not black:

However before I try to argue the point about binaries (oft my burden), I want for a moment to see how a play that predates the conception of inner self that is played out socially in the term ‘mental illness and health’ does to forefront precisely that development to come.

Psychiatry becomes to play a culturally central role in Western society in the eighteenth century and cannot be indicated in this play though the spectacle of James I of England (or the VI of Scotland and Banquo’s heir of long descent in myth who very much stressed hermetic interiority and invertedness). In Act 3 Scene 4 of Macbeth, the eponymous character sees and communes with Banquo’s Ghost at a feast organised for his nobles on becoming King- Banquo is an apparition seen by no-one else. At first he merely speaks strangely and not to the audience assembled but to someone or something only he sees – this production grateful did not flesh out Banquo’s Ghost in a visible actor’s embodiment. At first these symptoms are mild enough for Lady Macbeth to pass them off:

Sit, worthy friends. My lord is often thus And hath been from his youth. Pray you, keep seat. 65 The fit is momentary; upon a thought He will again be well. If much you note him You shall offend him and extend his passion.

Taking his cue from this perhaps, when the outward show of distress-laden interaction occurs, Macbeth too minimises the situation to his audience at the feast by a reference to his health:

I do forget.—

Do not muse at me, my most worthy friends.

I have a strange infirmity, which is nothing

To those that know me. Come, love and health to all. 105

Then I’ll sit down.—Give me some wine. Fill full.[3]

The clipped command ‘Fill full’ even resonates with his wife’s final ‘take seat’. These characters even act civility with an imperiousness of command. Yet, their joint reference to something mentally askew in Macbeth matters.

Of course, we can incline to think that the plotting pair here invent an illness to excuse the guilt (or fear of discovery of their secret by others – their feeling are on that range of scale from felt neurotic guilt to fear of detection of their wrongdoings) which racks them, but there is more than one reference elsewhere to the mental status of both the male and female leads of the Macbeth family, Even at the end, Macbeth talks like a victim of a severe and enduring outreach team’ (I used to be a member of one such) out to avoid medication at all costs. In Act 5, Scene 3, he is discussing how the mental trouble of his wife (she obsessively washes her hands in the manner of an Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, in modern terms):

……. Cure ⌜her⌝ of that.

Canst thou not minister to a mind diseased, 50

Pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow,

Raze out the written troubles of the brain,

And with some sweet oblivious antidote

Cleanse the stuffed bosom of that perilous stuff

Which weighs upon the heart? 55

DOCTOR Therein the patient

Must minister to himself.

MACBETH

Throw physic to the dogs. I’ll none of it.—

Come, put mine armor on. Give me my staff.

⌜Attendants begin to arm him.

Give me sixpence for the hearing of that – usually reasonably requested – from patients regulated by health institutions then I would be a rich man …. As the saying goes. Even self-help is cast off to the dogs by Macbeth as medication, which today it is – and a useless one at that. Macbeth is a play in which a Doctor of Physic takes a larger than usual role in Shakespeare, even though he is no equivalent to psychiatry – for he is servile as psychiatric consultants never are, so shaky is the foundation of their knowledge. The Doctor enters thrice.[4] Generally obedient as he turns out to be, Shakespeare’s early psychiatrist is beginning to know his worth, at least in his own assessment of his right for confidential information of his patients – here, in Act 5 Scene 1, Lady Macbeth:

DOCTOR A great perturbation in nature, to receive at 10 once the benefit of sleep and do the effects of watching. In this slumb’ry agitation, besides her walking and other actual performances, what at any time have you heard her say? GENTLEWOMAN That, sir, which I will not report after her. 15 DOCTOR You may to me, and ’tis most meet you should. GENTLEWOMAN Neither to you nor anyone, having no witness to confirm my speech. 20

Examine the Doctor’s words. They carry such ambiguity that characters interpret them as they will and in their interests as concerns the gentle Malcolm (yet keen to inherit his father’s throne, which as Duke of Cumberland he should) and that man of sterner stuff , ‘of no woman born’, Macduff. My own tendency is to find in the talk of mental distress much that is contingent in the text of the play to talk of sex/gender and its disturbance. The relation of sex/gender to behaviour is constantly linked to both prescriptions for behaviour and mental response to these scripts and their prompts to appropriate performance. They run deeper in this play than any other – notably in Lady Macbeth, who is continually disturbed by her husbands reputed(because presumably known best to her in private) lack of the stuff of manhood and fullness of that of the feminine – the ubiquitous ‘milk’ in the play. Receiving a note from Macbeth in Act 1, Scene 5 she lauds the fact of his rise in manly status as knight of the court (a thane held land mainly in recognition of the most manly of pursuits – military service in the name of the King):

Glamis thou art, and Cawdor, and shalt be

What thou art promised. Yet do I fear thy nature;

It is too full o’ th’ milk of human kindness

To catch the nearest way. Thou wouldst be great,

Art not without ambition, but without

The illness should attend it. What thou wouldst highly,

That wouldst thou holily; wouldst not play false

And yet wouldst wrongly win. Thou ’dst have, great Glamis,

That which cries “Thus thou must do,” if thou have it,

And that which rather thou dost fear to do,

Than wishest should be undone. Hie thee hither,

That I may pour my spirits in thine ear

And chastise with the valor of my tongue

All that impedes thee from the golden round,

Which fate and metaphysical aid doth seem

To have thee crowned withal.

Men don’t or shouldn’t quiver with either ‘kindness’ or moral questioning or indecision – it is a ‘milk’ that should be foreign to them as the breasts that express it. For it to do so is expressed as an ‘illness’ (expressed here even before any Doctor of Physic enters). She will prove that by invoking a rather opposing illness on herself a little late by unsexing – one of the chief signs of which is the metamorphosis of her inner ‘mil’ to something sterner and more toxic. She clearly marks her own invited illness by clearly characterising it as a form of adoptive uber-masculinity. The best image is that of the view that menstruation is an effect of thin blood, unknown to man as an emblem of ‘nature’s visitings’:

The raven himself is hoarse 45

That croaks the fatal entrance of Duncan

Under my battlements. Come, you spirits

That tend on mortal thoughts, unsex me here,

And fill me from the crown to the toe top-full

Of direst cruelty. Make thick my blood.

Stop up th’ access and passage to remorse,

That no compunctious visitings of nature

Shake my fell purpose, nor keep peace between

Th’ effect and it. Come to my woman’s breasts

And take my milk for gall, you murd’ring ministers,

Wherever in your sightless substances

You wait on nature’s mischief. Come, thick night,

And pall thee in the dunnest smoke of hell,

That my keen knife see not the wound it makes,

Nor heaven peep through the blanket of the dark 60

To cry “Hold, hold!”

Cush Jumbo could not have made these lines more meaningful than she does: sacrificing herself to what she sees as deficient in her husband – the ability to dry up the milk that succours the child within. And the child within Macbeth often appears in this production behind the glass of the inner scenes which often seem to represent his inner conflict, his long-held-onto pre-binary childhood. Transgender themes appear in the play often in juxtaposition to medicalised contexts. In the scene of the feast (Act 3, Scene 4) before referred to, after excusing Macbeth because of the trouble he has carried with him from childhood, she says aside to Macbeth only:

Drawing Macbeth aside.⌝ Are you a man? 70 MACBETH Ay, and a bold one, that dare look on that Which might appall the devil. LADY MACBETH O, proper stuff! This is the very painting of your fear. This is the air-drawn dagger which you said Led you to Duncan. O, these flaws and starts, Impostors to true fear, would well become A woman’s story at a winter’s fire, Authorized by her grandam. Shame itself! Why do you make such faces? When all’s done, 80 You look but on a stool.

Macbeth’s weakness of mind in his wife’s eyes belongs to that confusions of sex/gender which loom large as a contest in this play. The more questioned about his manliness, the more he asserts it from different criteria, only to be brought down by that being evidenced as another ‘proof’ against his sex/gender status. Weak and feminine men only see visions of what is not there, she says – a thing she might also evidence, were she half-aware of it by her nightly visitations of sleepwalking and obsessive hand wringing.

Macbeth performs the man wonderfully. He uses it as excuse for killing the retainers of Duncan so that the blame for his murder might linger on them, even when questioned by more politic but nevertheless ‘real’ men like Macduff (Act 2, Scene 3):

MACBETH

O, yet I do repent me of my fury,

That I did kill them. 125

MACDUFF Wherefore did you so?

MACBETH

Who can be wise, amazed, temp’rate, and furious,

Loyal, and neutral, in a moment? No man.

Th’ expedition of my violent love

Outrun the pauser, reason. 130

I did it BECAUSE I WAS A MAN, he asserts. Of course, it is true that Macbeth is never behindhand in his valour as a warrior and perhaps his professions are matched by that of his performance, though we never in this clever production so good with a long sword than Macduff. Macduff’s masculinity is off the scale – even symbolically. A ‘Bloody Child’ known in the text as Second Apparition says to Macbeth on his return to the Witches in Act 4, Scene 1:

SECOND APPARITION

Be bloody, bold, and resolute. Laugh to scorn 90

The power of man, for none of woman born

Shall harm Macbeth.

There you have it – what it is to be a man is a quibble. For only a man who has never known a woman in his formative years can kill Macbeth. And that is Macduff – from his mother’s womb ‘untimely ripped’ and hence a child bloodied by the loss of enduring feminine influence – will kill him. There could be no clearer indication that ‘to be a man’ as opposed to ‘act as a man’ is a contested theme of the play. Macbeth tells the Ghost of Banquo this (Act 4, Scene 3):

MACBETH ⌜to the Ghost⌝ What man dare, I dare. Approach thou like the rugged Russian bear, The armed rhinoceros, or th’ Hyrcan tiger; Take any shape but that, and my firm nerves Shall never tremble. Or be alive again 125 And dare me to the desert with thy sword. If trembling I inhabit then, protest me The baby of a girl. Hence, horrible shadow! Unreal mock’ry, hence!⌜Ghost exits.⌝ Why so, being gone, 130 I am a man again.—Pray you sit still.

He says to all intents; ‘I am a man as long as my vision is not disturbed from the norm by things that bridge the realms of inner and outer, being and performing, imagination and reality’. Is Macbeth ‘the baby of a girl’? Is he so ‘weak’ by the standards of the binary?

Marianka Swain is correct in saying of this production: ‘Children are everywhere, whether Banquo’s son or Macduff’s doomed boy, or haunting the soundscape with giggles or screams’. [5] Children matter a lot in this play – one reason why the New Criticism in the form of L.C. Knights (we used to call him ‘Elsie Knights’ at school) got it wrong by mocking A.C. Bradley for asking, “How Many Children Had Lady Macbeth”. This production brilliantly put them back on the visible and invisible agenda through their presence on an inner stage behind actors as well as by casting similar-looking boys in the role in non-apparent gender trappings (we see I think Casper Knopf as Macduff’s Son/Fleance/Young Siward).

I have taken some time and used too much indirection above in order to show why usually I hate to see this play staged. In brief, it is because it is a play of inner not external action that strikes me as too often tedious if approached as too often as an ‘action play’. It is a passive or ‘passion’ play that is enacted in the interiority evoked by its very great blank verse (perhaps the most subtly greatest in Shakespeare, despite King Lear) and much nearer to the lines of Christopher Marlowe in subtle music. You respond best to that in the theatre as Cummings and the Donmar have done. You interiorise the play by subtle methods as well as more obvious ones.

One way is to emphasise the alienation effects (as Brecht would have called them). Jatinder Singh Randhawa (The Porter/Seytan) does this brilliant as The Porter by enacting him as stand-up comic continually reminding the audience of their status qua audience rather than as in a role in which they forget themselves – even to the point of branding holders of front row seats as being obviously rich – given the price of London theatre currently, or referring to their earphones (of which more a little later). Lukowski picked up the words in his review, though he interprets them superficially. You may be in awe of the ‘sound design’ but do you not also get jogged to try and understand its cognitive and emotional effects:

Jatinder Singh Randhawa’s Porter ….– contains the memorably droll observation ‘this is just watching a radio drama isn’t it?’. It feels like it punctures a certain tension – perhaps diffusing the idea that we’re supposed to be in absolute awe at the sound design.[6]

That may detract from the fact the Porter too takes the debate about makes a man a man down to ground level, in the original text but if it does so, it also yields many other advantages in compensation. Nevertheless the binary of desire and performance is an important indicator of a man here and elsewhere, so dependent is he on the idea of the phallus as weapon. In Act 2 Scene 3, asked what use alcoholic drink is the Porter says:

Marry, sir, nose-painting, sleep, and urine.

Lechery, sir, it provokes and unprovokes. It provokes 30

the desire, but it takes away the performance.

Therefore much drink may be said to be an

equivocator with lechery. It makes him, and it

mars him; it sets him on, and it takes him off; it

persuades him and disheartens him; makes him

stand to and not stand to; in conclusion, equivocates

him in a sleep and, giving him the lie, leaves

him.

‘Giving him the lie’ is an important a line as any in the play in summarising the dilemma of men in it (and lady Macbeth who crosses the binary boundary to her death). However, this production uses it to show that men are things of performance, not either desire or fact of birth (even Macduff who plays the role of a man who never needed do with women except as a container men spring forth out of).

The other strategies can in part be seen in the collage above and include the stage within a stage that is bounded by glass behind the individual actors (often behind Macbeth is an ‘inner’ boy banging on the glass but otherwise the ensemble acting as a kind of Greek chorus often, as with that chorus, to musical and dance movement accompaniment (live music came from an onstage Scottish folk band led by Macrae and featuring award-winning Gaelic singer Mairi MacInnes). In one scene the sleepwalking Lady Macbeth walks behind the main stage with a candle. Arifa Akbar in The Guardian’s review describes this brilliantly:

Bruno Poet’s lighting shines hard spotlights across the gloom. The cast, along with musicians, stand in a lineup in the glass box, a row of pale staring faces that look as if they are floating, disembodied in darkness. In some scenes they bang the glass or press their faces against it unnervingly.[7]

The reason I do not favour the reading of Macbeth’s character in this production as simply nasty as in Swain and Lukowski’s reviews is that oft this staging and lighting effect isolates Tennant from an occurring sociality occurring behind him, where the insignificance of one person’s nuance (and why not a male with a tendency to the ‘milk of human kindness’) . In the image below, Tennant’s dishevelled state is felt to be that of an outcast whatever his sins.

How much more so when his little dagger or dirk is lifted to potentially end his own life, whilst the hoi polloi have shifted their heads to look the other way as if at a public tennis match. It is a fearsome still even and captures the actor, looking not a bit like Doctor Who, as Swain suggests.

The voices of some supernatural parts (suitably edited to rid it of Hecate) like the witches or ‘weird sisters’ (another sex/gender play) in their first appearance ‘appeared’ only as imagined in sound. Lukowski expresses this with a populist elegance, saying that in the theatre the headphones played:

… a constant stream of 3D sound to be relayed to your ears: the screeches of birds, music from musicians in the mic-ed up glass chamber at the back of Rosanna Vize’s stark, monochrome set, and most impressively a ‘three sisters’ who are wholly physically absent, just disembodied voices whose location we feel we can ‘see’ thanks to the pinpoint design.[8]

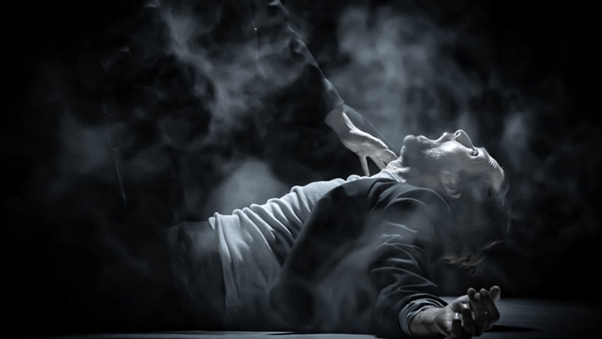

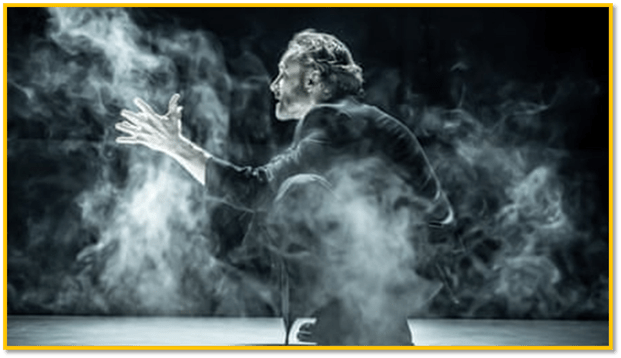

However Swain also points out that sound speaks also to disembodied physical effects of light and gaseous material:

Eerily, Gareth Fry’s soundscape layers in elements that don’t appear on stage – whether lingering battle cries or the voices of the witches, whose only physical presence is curls of smoke.[9]

But these have force when combined with performance that captures human reaction carefully and not melodramatically as with Macbeth in the struggle of uncomprehending fear in the case of Macbeth or Banquo (Cal MacAninch) lowering his height on stage in question to its lack of answering visual body:

The cinema had to apply Dolby Stereo effects – the original production put the audience in earphones. It is difficult to imagine the theatrical effect from the streamed version. Lukowski found it irritating at first, fascinating later We probably miss some of the inner psychological effects of having the Jumbo Cush and David Tennant dialogue oft played between the ears of a stereo binaural headset (a strange experience in anyone’s book as any student of classic cognitive-psychological divided attention can tell you) must have been, at the least, ‘spooky’ – like hearing voices from different brain regions).

Some of the more physical action used the white stained space of a central stage that isolates the figure acting in an empty space in which time and space dimensions can be queered.

That neatly edged raised space can be used as if it were a prop – a table at which Macbeth met his murderous employees (below) or the table for the Feast, as it were, of Banquo.

Using that space in Act 4 Scene 3 created a divide from the physical action (even though the Scottish nobles played by the choric ensemble were just eating at a table) from its use concurrently a space that was more private and intimate which in the feast scene put the Macbeth’s private talk on it, whilst to all intents and purposes it was still a table. This incorporated the audience into the division of registers of poetry in the play – from that most inward to hat most public. It made the soliloquies brilliant, for it afforded their perception as spoken in space interior even to the actor. The glass of the inner space stage at the back offered reflections when helpful. The great Bruno Poet did the lighting, used as he is to create inner space that way.

The play opens with its intent on private symbols in private space on show. We see only for a moment the lit rectangular stage with a bowl of water (in glass I believe) at its centre. The clear water receives drops of blood in it as Macbeth enters eventually from above to finally wash his hands in it. Hand washing then is focused from the get-go, as is the concept of diluted blood. Yet at the end and through the curtain call the ensemble stand above the stain od Macbeth’s blood (see the collage below bottom right).

But another reason I could not compare Cummings Macbeth to Tennant’s is that they incomparable as vehicles for each actor respectively. The brilliance of the Max Webster production is in part that of the Casting Director’s Anna Cooper for here was a cast that gaged the relation of what we used to call ‘principals’ and company, such that hierarch in performance was not in our mind except as in the representation of a hierarchical society. What a cast!

If you can see this do. Geoffee and me loved it.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Marianka Swain (2023) ‘Macbeth’ review – David Tennant is a terrifying moral vacuum in this lean, mean production in London Theatre (online) (16 December, 2023, 15:00) Available at: https://www.londontheatre.co.uk/reviews/macbeth-review-donmar-warehouse

[2] Andrzej Lukowski (2024) ‘David Tennant is a chillingly single-minded Macbeth in this idiosyncratic take on The Scottish Play’ in Time Out (Tuesday 23 April 2024) Available at: https://www.timeout.com/london/theatre/macbeth-83-review

[3] Macbeth 3 (iv) from The Folger Shakespeare text online: see https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/macbeth/read/3/4/?q=strange%20#line-3.4.102

[4] Ibid: Act 4, Scene 3 158 – 166, Act 5, Scene 1 0 – 84, Act 5, Scene 3 0 – 58.

[5] Marianka Swain, op.cit

[6] Andrzej Lukowski op.cit.

[7] Arifa Akbar (2023) ‘Macbeth review – David Tennant thrills in this high-concept production’ In The Guardian (Sat 16 Dec 2023 00.00 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2023/dec/16/macbeth-review-david-tennant-thrills-in-this-high-concept-production

[8] Lukowski op.cit.

[9] Swain op.cit.