Let’s break from tradition, but only so we can go on, and on, and … and the status quo can keep on going on as it is.

The thing about words is that, as I keep endlessly and no doubt obseesively repeating in these blogs, they not only change their meaning but also preserve the older meanings within the newer one. The idea of a ‘break’is one such word. So here we go again to query etymonline. What that reveals is that root of the word is in Old English and that it’s also nation was from the first always associated with a break caused by violence or major stress or pressure. Something painful!

break (v.) : Old English brecan “to divide solid matter violently into parts or fragments; to injure, violate (a promise, etc.), destroy, curtail; to break into, rush into; to burst forth, spring out; to subdue, tame” (class IV strong verb; past tense bræc, past participle brocen), from Proto-Germanic *brekanan (source also of Old Frisian breka, Dutch breken, Old High German brehhan, German brechen, Gothic brikan), from PIE root *bhreg- “to break.” / …

Of bones in Old English. Formerly also of cloth, paper, etc. The meaning “escape by breaking an enclosure” is from late 14c. The intransitive sense of “be or become separated into fragments or parts under action of some force” is from late 12c. The meaning “lessen, impair” is from late 15c. That of “make a first and partial disclosure” is from early 13c. The sense of “destroy continuity or completeness” in any way is from 1741. Of coins or bills, “to convert to smaller units of currency,” by 1882.

break (n.) : c.1300, “act of breaking, forcible disruption or separation,” from break (v.). The sense in break of day “first appearance of light in the morning” is from 1580s; the meaning “sudden, marked transition from one course, place, or state to another” is by 1725.

The sense of “short interval between spells of work” (originally between lessons at school) is from 1861. The meaning “stroke of luck” is attested by 1911, probably an image from billiards (where the break that scatters the ordered balls and starts the game is attested from 1865). The meaning “stroke of mercy” is from 1914. The jazz musical sense of “improvised passage, solo” is from 1920s. The broadcasting sense is by 1941.

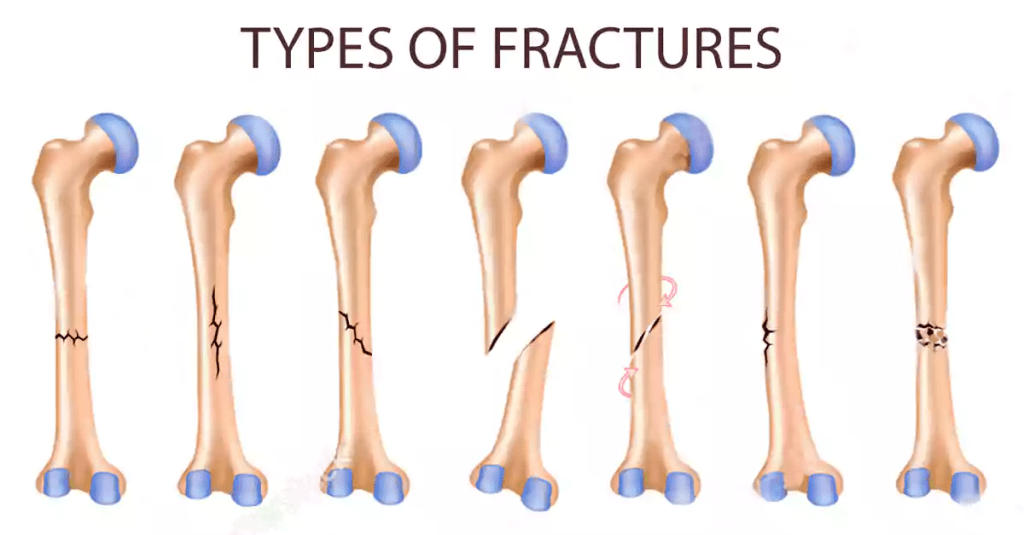

That the noun derived from the verb is important. A break starts as a willed action or a consequence of an accident like a fall embued with, as it were, implied agency: “that fall broke in my leg”, before it is a thing in itzelf, a painful fpr whi h empathyis sought. Let’s stick with the obvious painful stating point of the word – a broken leg, the most likely event in early England to lead to the immobilisation of bipedal humanity. People sometimes ask:

That is a serious question! The answer is that, semantically, there is no difference in medical usage between the words, even if we are tempted to.imagins that there is one in common-sense based on the fullness or otherwise of the break or fracture. Any loss of integrity in a skeletal bone can be called a fracture and a break.

But this prompt asks for that meaning of break that originated, according to etymonline in 1861, with regard to breaks between learning sessions in schools and is now generalised mainly to breaks between sessions or periods of work. It began to mean something like the modern meaning of holiday. We could take a short break then even without thinking of a return to something from which we have broke off. Even tne retired take ‘short breaks’ to Amsterdam.

How do we understand then and play significant games with the word “break” in our WordPress prompt? Read quickly and without deliberation, the question has the soppy modern assumption in it that breaks are always capable of being put together again, that having broken from work or school wevwill return and the status quo will re-establish itself. The “break” is one we wanted and will give us pleasure we think; if only because we are within that break in control of the use of our own time, not bound to the turning wheel of events serving others or our own needs. These breaks are the opposite of pain, it seems, for they constitute the withdrawal of painful, or at least arduous necessities.

But they are bounded with conditions; not least of time. A break that resembles a fra tire involves not only pain but also necessary and adaptive change. The change required may be only in the person suffering the break though civilised values suggest that, if someone else is ‘broken’ in some way, others too adapt to accommodate their changed capacity to ensure their own survival. The learning g embraced is that everything that prevailed in the past cannot be expected to continue to prevail now or in the future.

In a whole society, a break from the ways of the past top is a break from the ways and the people involved in the making, uses, meanings, and distributions of goods in society. Revolutions in their infancy claim that their break with the past is absolute and that what is broken by revolution is made anew. Wordsworth, remembering his experience of the French Revolution but very definitely maintains its joys in a past that he suggests may have been immature, says:

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,

But to be young was very heaven!—Oh! times,

In which the meagre, stale, forbidding ways

Of custom, law, and statute, took at once

The attraction of a country in romance!

When Reason seemed the most to assert her rights,

When most intent on making of herself

A prime Enchantress—to assist the work

Which then was going forward in her name!

Not favoured spots alone, but the whole earth,

The beauty wore of promise, ....

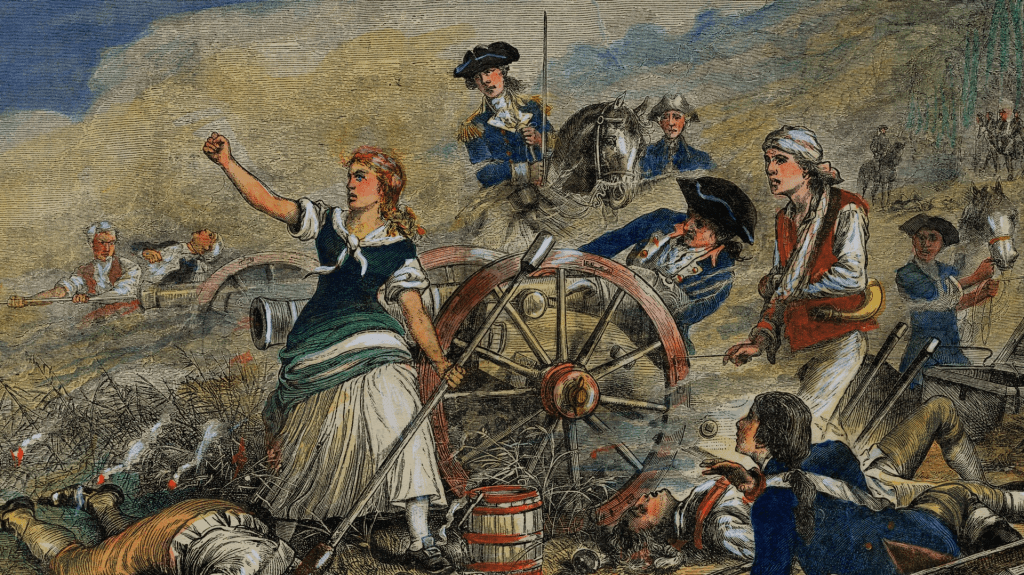

The Romantic paradigm, at its freshest in Goethe, Schiller and in Beethoven, loved the ide of renewal.where youth and dawn claimed the right to chase away what was ‘meagre, stale, forrbidding’ in its repressive ways and see the whole world as transformed into ‘romance’ by an ‘Enchanter’. The very voice of poetry and music was that liberating ‘chant’, singing the measure of new ways, a Marsellaise, for instance, sometimes with necessary violence in its wake. Law and statute could not be the same as ‘custom’ for custom was broken and ought to die, making way for statute is new, for we have broken away from it forever (or so we think). The final break is when the Ancien Regime loses its head with a very clean break.

But all Revolutions on earth have seen either a Restoration of what went before, if changed for its own safety and with an idea of enduring longer this time round, whether in England wherein the Glorious Revolution constituted a continuum of the idea of Restoration or in differing ways and fashions many times in France Including Napoleonic Imperialism. But that does not mean the break constituted by those revolutions was meaningless or a thing history would be better off without. The pain they involved enforced change even if the change had to have bits of the past, or the look of the past, restored to it. There is a sense in which without such revolutions capitalism could never have achieved the global hegemony it now has. Ay! But there;’s the rub.

The important thing about change is a lesson I learned from the best politico-historical novel ever written,Lampedusa’s The Leopard, in which an aristocracy learn to make their peace with a boldily emergent bourgeoisie hungry for power: ‘If you want things to stay as they are, things will have to change’, is the significant mantra within it (for my blog on the novel see this link). That, in a sense, is the meaning of the modern word ‘break’ evoked in this question – if you want to carry on serving needs, which you think your own but rarely are, then you need a ‘break’. It won’t be painful whilst it happens but it will be when it ends with your return to the unjust status quo. One extreme of this is the concept of the ‘carer’s break’ where friends, family or supporters who care for someone unpaid are deemed by institutions of social care to be worthy of a break, but it is a break that won’t change their lot or allocate resources to them in the long term. They must return to that that wears them away, sometimes to the point of erasure, and be grateful for day care or respite that has managed to upset everyone, including the one cared for, in ways that are oft counter-productive in the meanwhile. In our present parlous condition that no government dare address the ‘break’ that most carers get is a return to the old meaning of the word – and thet sometimes remain broken. I am not a carer any more (my husband has recovered beyong hope – but I had a taste of where the fractures in me would occur, had it continued.

A new filming of The Leopard comes to Netflix

Meanwhile the present government feels that it cannot afford to address community care with resources but can address what Rachel Reeves calls the ‘nom-dom community’ (people with vast unearned income untaxed because they do not live in Britain or much contribute to it). We need a break and this Labour government is NOT giving us one – just a growth mantra which will not, nor cannot, break the downward spiral to ecological disaster and increasing injustice. Sometimes we need that edge of revolutionary discourse: the admission that though revolutions are neither nice or easy to control, they are needed to help us to change. No doubt capitalism will restore itself thereafter. As Marx says, capitalism thrives best in constant revolutions – if not ones that redistribute power. However, hopefully it will do by some Glorious Revolution itself that so modifies the state that the whole population is not broken in the mill of otherwise inevitable ecological breakdown and has some unbroken integrity returned to it.

But I feel fractured, don’t you! I don;t feel relief coming very soon.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx