G.K. Chesterton wrote What’s Wrong with the World’ in 1910 and I have, I have to admit, never read it but I did search out a context for the quotation that is a little wider and here it is:

“Nobody says, “This washerwoman rips up the left leg of my pyjamas; now if there is one thing I insist on it is the right leg ripped up.” The ideal washing is simply to send a thing back washed. But it is by no means true that the ideal cooking is simply to send a thing back cooked. Cooking is an art; it has in it personality, and even perversity, for the definition of an art is that which must be personal and may be perverse. I know a man, not otherwise dainty, who cannot touch common sausages unless they are almost burned to a coal. He wants his sausages fried to rags, yet he does not insist on his shirts being boiled to rags.”

What Chesterton points to is that the word ‘cooking’ carries nuance of a different kind from the verbs and adverbs describing other activities. To be considered ‘cooked’, a thing must meet certain criteria – some of the straightforward and normative, others more ‘perverse’ because fitted to individuated tastes which strike others as incorrect or wrong but only because their tastes differ, in their most perverse forms. Cooking, even without the matter of individual taste can be contentious. It seems a straightforward enough concept, but take the programme Masterchef.

Soon after the cooks on the show – be they Professional, Celebrity or everyday people without undue celebrity – become acclimatised, standards raise. There has never been a version of the beginning of the show where eventually Gregg Wallace (now replaced for the next series by the classy – in every sense of the word – Grace Dent) to say – “it’s nice what you’ve done but it involves hardly any ‘cooking'”. For this reason, I tried to see if a definition would help me, taking Mirriam-Webster’s online dictionary. Here is their section on the verb ‘to cook’:

Mirriam Webster definitions (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/cook) of cook as a verb addresses the forms cooked; cooking; cooks

as a transitive verb

1: to prepare (food) for eating by a heating process:

Cook the vegetables over low heat for 10 minutes; The fish was cooked in a wine sauce; He cooked dinner for his guests.

2: concoct, fabricate —usually used with up:

cooked up a scheme

3: to alter (something, such as records) with the intention of deceiving or misleading : falsify, doctor:

The point is that every country's numbers are the result of a specific set of testing and accounting regimes. Everyone is cooking the data, one way or another.—Alexis C. Madrigal see also cook the books

4: to subject (something) to the action of heat or fire during preparation

Agents discovered a recipe for cooking meth at his lab …—Andrew E. Serwer

as an intransitive verb

1: to prepare food for eating especially by means of heat:

We're too busy to cook tonight; I enjoy cooking for friends.

2: to undergo the action of being cooked

The rice is cooking now.

3: occur, happen

She tried to find out what was cooking in the committee.

4: to perform, do, or proceed well:

The jazz quartet was cooking along; The party cooked right through the night.

Phrases: cook one's goose : to make one's failure or ruin certain.

The metaphoric uses of the work are interesting: sometimes indicating that what is needed to be done is being done and appropriately rather than inappropriately (as in meaning of the transitive verb number 4 which resembles the context in cooking proper in meaning 2). But some parts of some definitions allow for ambiguity. As a transitive verb, it seems that you, if you agree this definition, cannot ‘prepare’ food unless you are heating it alone or with other materials as part of the process, although as an intransitive verb the latitude is allowed for other forms of preparation not involving the application of heat. This is necessary since in some cuisines the art of cooking is more to do not with transforming food by heating it but rather than merely combining it with other elements (some salads), chopping and / or mixing it in a certain way (as in julienne vegetables) or seasoning it differently without using heat at any point (as in steak or lamb tartare). Of course cooks don’t help us. Nigella Lawson describes her steak tartare as ‘not requiring cooking’ and for many a thing isn’t cooked if it isn’t heated however well prepared it is by kitchen processes.

But allow me this latitude, cooking is essential a process of transformative preparation from the raw and the cooked, and there is therefore a sense in which combining, mixing and seasoning alone can be describing then as cooking for rarely are people as crude as to eat things they call raw. of course, the French create difficulties – crudities (meaning raw things) are essentially a course in a French meal that is an exception that tests the rule – but it also ‘proves’ the rule (in the modern sense for the old one meant ‘test’ the rule) for no-one would forgo the preparation of the raw vegetables before they are processed.

The main metaphoric use of the term ‘cook’ means to so change the nature of the thing you process you falsify it, or at least ensure that the process of its making (or fabrication) can at some point be made evident. The sense that the cooked is a kind of ‘lie’, or, at least, a fiction, really matters. Indeed etymologically I sense that too. Here is etymonline.com (note that https://www.etymonline.com/word/cook) still only gives us implicitly the source of the problem in the word) :

cook (n.)

“one whose occupation is the preparing and cooking of food,” Old English coc, from Vulgar Latin *cocus “cook,” from Latin coquus, from coquere “to cook, prepare food, ripen, digest, turn over in the mind” from PIE root *pekw- “to cook, ripen.”

Germanic languages had no one native term for all types of cooking, and borrowed the Latin word (Old Saxon kok, Old High German choh, German Koch, Swedish kock).

There is the proverb, the more cooks the worse potage. [Gascoigne, 1575]

cook (v.)

late 14c., in the most basic sense, “to make fit for eating by the action of heat,” but especially “to prepare in an appetizing way by various combinations of material and flavoring,” from cook (n.).

Old English had gecocnian, cognate with Old High German cochon, German kochen, all verbs from nouns, but the Middle English word seems to be a fresh formation from the noun in English. The figurative sense of “to manipulate, falsify, alter, doctor” is from 1630s (phrase cook the books is attested by 1954). Related: Cooked, cooking. Phrase what’s cooking? “what’s up, what’s going on” is attested by 1942. To cook with gas “do well, act or think correctly” is 1930s jive talk.

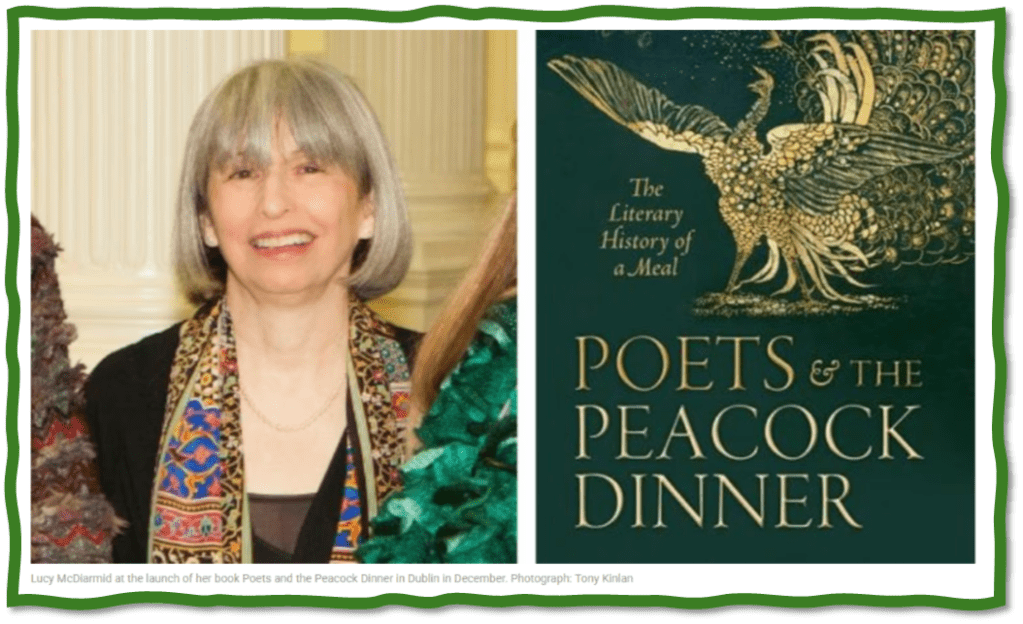

What I still need to know here is whether, if a ‘cook’ is “to prepare in an appetizing way by various combinations of material and flavoring,” they are still doing ‘cooking’. Are they? I think so. And they are creating a story or fiction, for that is what a ‘recipe’ is and sometimes the perversity of the recipe and its arcane materials appeals to perverse literary tastes (I am thinking of Lucy MacDiarmid’s fantastic telling of a story of inviting seven poets including Ezra Pound to dine on peacock).

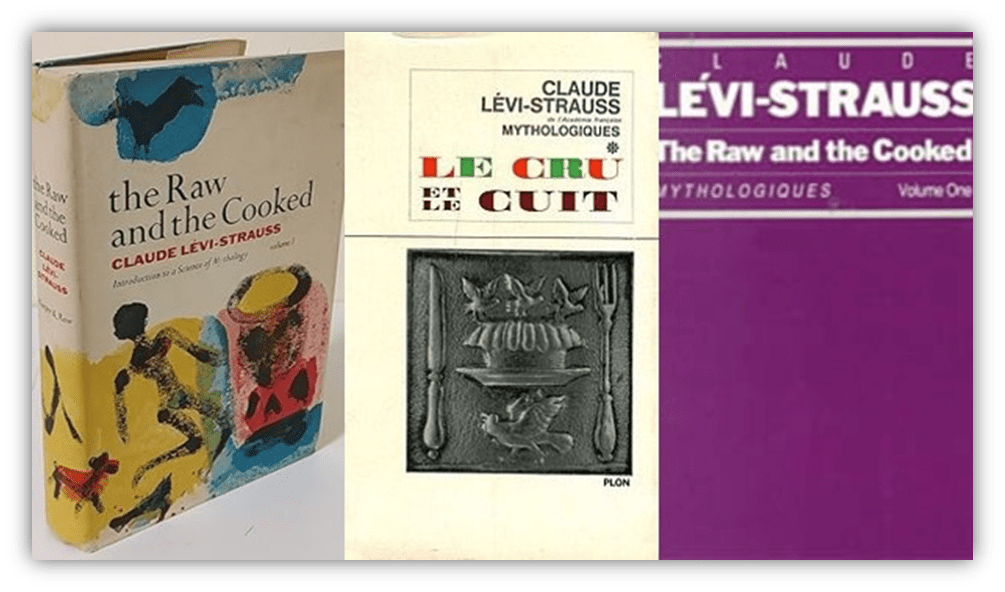

Consider the association too with ripening. I was once at a dinner party where served pheasant, one diner still insisted not on the recipe as such but the duration the newly killed bird was hung to ‘decay’ or be enriched (however you view this idea) before being served. My point is (overlaboured as always) is that it to eat the raw is not socially acceptable – not because of hygiene considerations altogether but because we want our foos to tell us a story about the kind of people we are, either as a social group or an individual – even the man who liked his sausages burnt in Chesterton. As such cooking is a means of reproducing social values and eccentric versions of those values. Hence for Claude Lévi-Strauss it was the necessary starting point in considering social mythologies, and for later social theorists, ideologies (Roland Barthes for instance). Lévi-Strauss mattered a lot to me when I was a student and his book The Raw and the Cooked probably (though it was in fact the first volume of a larger work on the mythologies uncovered in anthropology) the most important of his works. Below is the Wikipedia description thereof:

The Raw and the Cooked (1964) is the first volume from Mythologiques, a structural study of Amerindian mythology written by French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss. It was originally published in French as Le Cru et le Cuit.[1] Although the book is part of a larger volume, Lévi-Strauss writes that it may be appreciated on its own merits, stating that he does not consider this first volume a beginning “since it would have developed along similar lines if it had had a different starting point”.[2]

In the introduction, Lévi-Strauss writes of his confidence that “certain categorical opposites drawn from everyday experience with the most basic sorts of things—e.g. ‘raw’ and ‘cooked,’ ‘fresh’ and ‘rotten,’ ‘moist’ and ‘parched,’ and others—can serve a people as conceptual tools for the formation of abstract notions and for combining these into propositions.” Beginning with a Bororo myth, Lévi-Strauss analyses 187 myths, reconstructing sociocultural formations using binary oppositions based on sensory qualities.[3] The work thus presents an adaptation of Ferdinand de Saussure’s theories of structural linguistics applied to a different field.[4]

For me the fact that binary constructs actually were the base of social mythologies mattered then and matters now, though they can interact in a nuanced way (consider the ‘fresh / rotten’ binary, for instance in the light of my anecdote about the eating of game in posh dinner parties, where fresh almost takes on the negative associations of ‘raw’. In my view the transition between the ‘raw’ and the ‘cooked’ is also one where the basis of truth is necessarily fictionalised in order to make an everyday story into a literary work, a truth into an acceptable fiction that we can live with. One source of this cooking process is the means to rationalise truths about things facts that are inconvenient – the exploitation of the many by the few, the murderous activities of ‘just wars’ (for a just war is only just to its victors) or the pruning of the sexual from the romantic, the body from the spirit. In all these cases ‘raw’ truths are considered the stuff of the ‘crude’ thinker. Sometimes I want to shout: Let me be ‘raw’ as well as let me be ‘crude’, for much gets lost in the cooking of the truth into books – one way in which art is sometimes a ‘cooking of the books’.

So:

What is my favourite thing to cook?

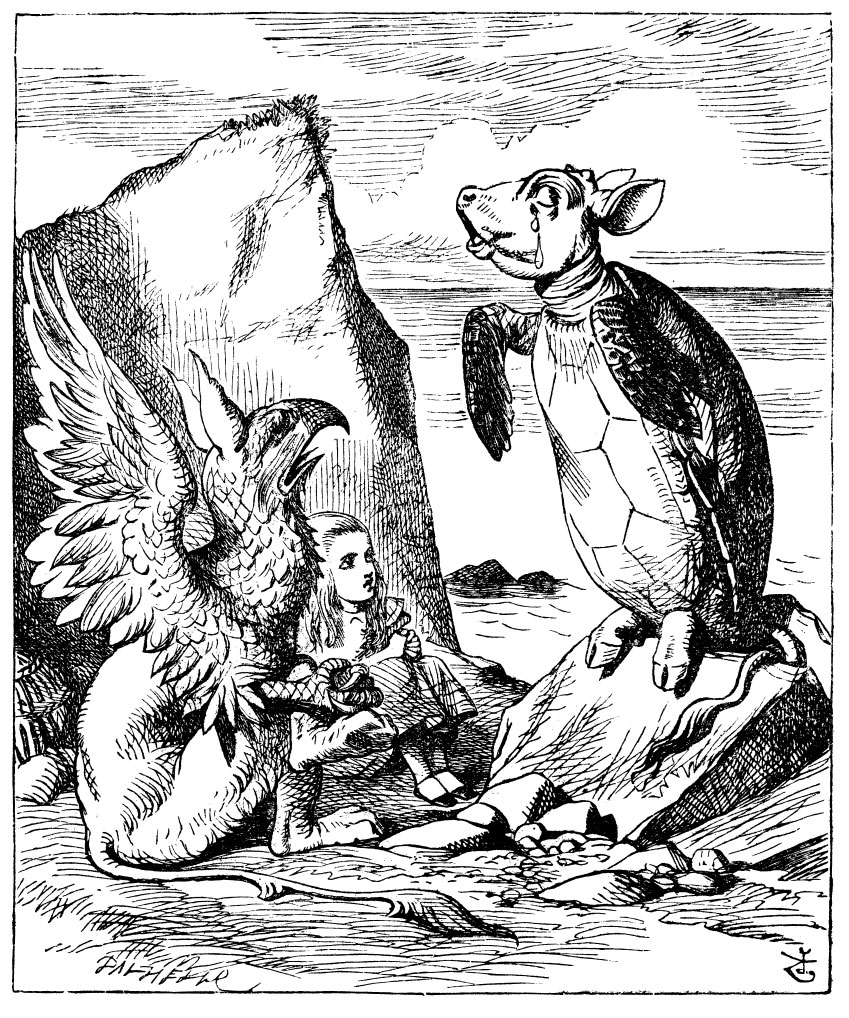

My answer: anything that can be ‘deconstructed’ so we know what it is, not what it pretends to be Carroll made a similar point in his story of the Mock-Turtle, for Mock-Turtle Soup is actually made from the flesh and viscera of calves, though it apes a more ‘expensive’ item, but is anyway as much as abomination (for he understood ‘meat is murder’ as would the vivisection of a calf’s head onto a turtle body and instructing the product to stand uptight like a human and belie its nature:

To turn the Mock-Turtle’s clever song about lobsters into a song called ‘Beautiful Soup’ is therefore another modern (if not very modern) abomination and no wonder the calves head on the hybrid cries:

Anyone fancy being cooked for my delectation?

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx