‘Gladiator II’ is a turkey – not least because it goes to great lengths to avoid being a queer turkey!! The inheritance of heroic Roman Republican virtue, aptitude for bearing a sword, and heteronormativity in Ridley’s Rome.

Posted on by stevendouglasblog

Weighed down with excess swordplay in the best cine-poster for Gladiator II , Paul Mescal’s dual swords seem to droop, until you realise that one is pointed, extended below the picture space in which it appears, to the end of the credits for his name on the poster, the other poised to pierce the name of Denzel Washington from above. In the poster, the swish of the Gladiator’s leather skirt-like appendages used as waist wear (or like a skirt that piece of Roman military clothing looks here) appears to happen largely in order to show a piece of Paul Mescal’s shapely thigh.

Denzel Washington feels to me the only actor who genuinely acts in Gladiator II, though his role is that of the almost pantomime villain. However his ability to play the bisexual Macrinus as a former slave of war (captured in an African campaign), rising as a gladiator to the leadership of gladiators under his tutelage of an elect gladiatorial troupe intended for shows at the Colosseum, has a lot to do with a film actor of long varied experience. As an emperor, he dresses, gestures, and poses for the part he plays naturally, as film actors are wont to do:

Macrinus is in the film a bisexual man who can pass as straight entirely, amongst a camp of camp followers who lounge about drinking on couches in his scenes showing him at leisure, and swapping smutty jokes about tasting the product (the gladiators he means) before exposing them to others with Tim McInnerny. The latter is playing the unsavoury and decidedly closet but soooo obviously queer Senator Thraex.

Washington’s character barely resembles at all the Emperor Macrinus on whom he is based except for his Machiavellian power seeking, although a directorial note on the film shares that Ridley Scott believed thecresl Macrinus to be both bisexual and cruel to underling gladiators, as if these were cognate qualities of character.

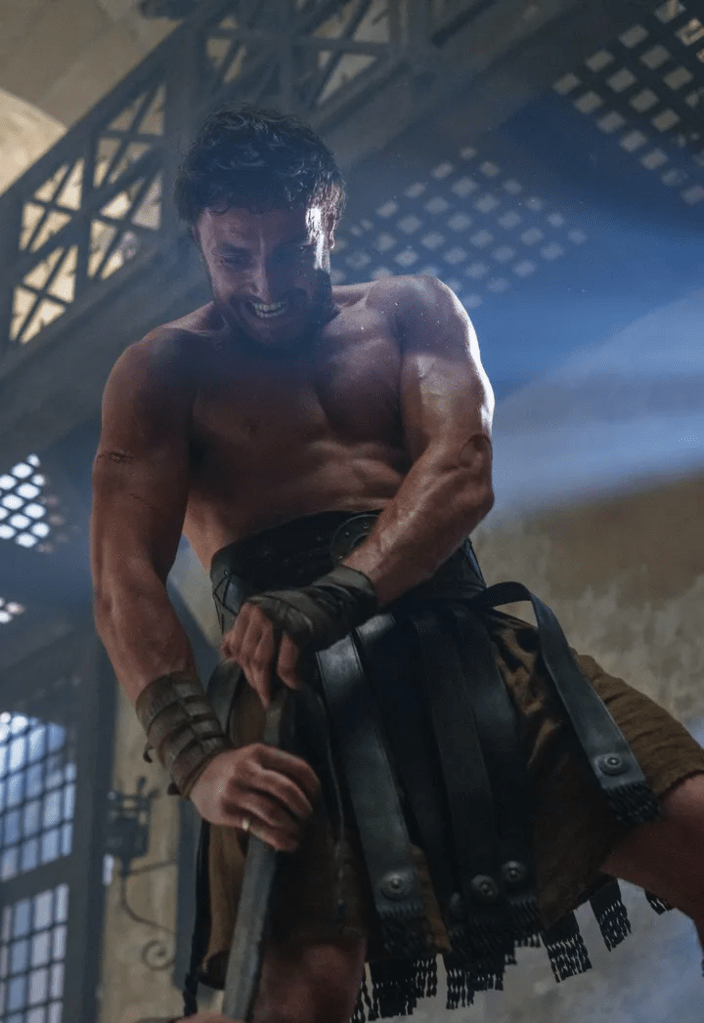

Mescal, I think, acts brilliantly in All Of Us Strangers (see my blog here) as the ghost of a lonely queer young man looking for love and company. However, here he plays the beefcake hero he probably is, decidedly heterosexual from the start with his warrior princess killed in battle by order of A-class beefcake, General Acacius [Pedro Pascal]. At the finish he adopts the role of his father, Maximus, as a Spartacus-like rebel republican and realises the decent and manly Republican warrior qualities of Acacius, despite the latter having ordered his African princess-wife’s death.

A-class beefcake, General Acacius [Pedro Pascal]

Russell Crowe’s believable male hunk, Maximus, does not lead us to see Mescal as a hero that is Maximus’s Minimus. However, when asked to compare the two actors as gladiatorial film material, Ridley Scott told ScreenRant that he could tell that Mescal had spent more time in the theatre than as a film actor. The hint of theatrical or actorly qualities sticks; although Mescal is too young to remember when both the terms ‘musical’ and ‘theatrical’ were ‘polite’ synonyms for queer. Scott did not elaborate the point in this manner, though. As for Mescal, he may have felt the comparison requested already damaging to his masculine self-esteem in lots of ways. Note then another point in ScreenRant:

… Mescal revealed that he actually didn’t even contact Crowe for help when he signed on to make Gladiator II. Upon reading the script for Gladiator II, Mescal recognized Lucius as a completely different person than Maximus, which explains why he didn’t contact the Oscar winner. This also emphasizes that Mescal is confident in his own abilities and Scott’s ability to direct him.

The comparison is evoked constantly in the film, even before we are actually overtly informed of his part princely and part beefcake parentage. A loyal slave takes Lucius to see his father’s tomb, inhabited by only a buxom breastplate, and, of course, his father’s monstrous sword; a phallus to be proud of that Mescal glances at enthralled.

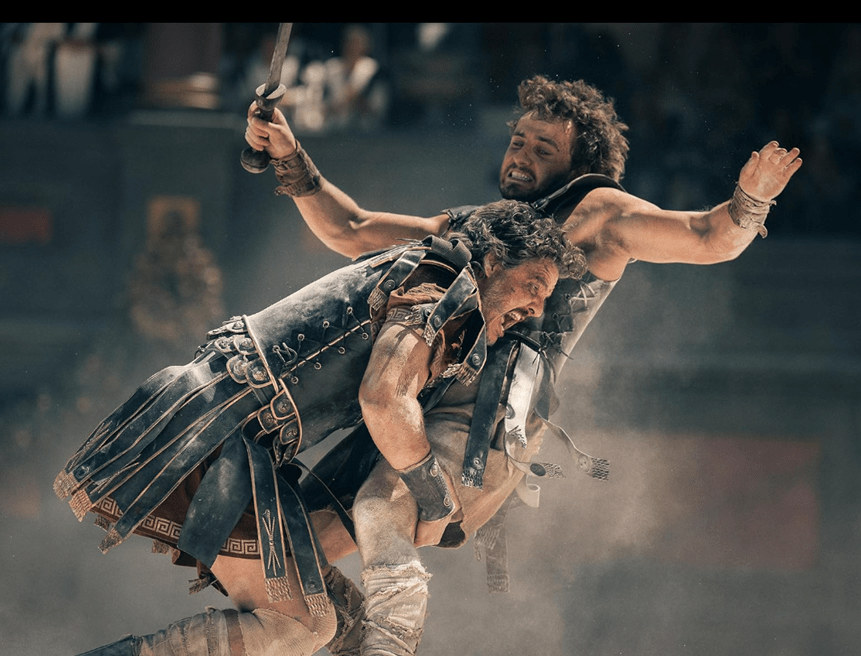

Yet, as a fighter Mescal exposes muscle in ways that are all man, taking on many men better armoured and defended.

Moreover, people notice, especially his mother Lucilla, the Dowager Empress [Connie Nielsen], that he has traits established almost genetically, but perhaps also by mimicking reports, from Maximus; including rubbing the dry grit of the Colosseum arena into hands that might be otherwise sweaty, his sword handy by his side:

But Rome is degenerating in Ridley’s take on it – a take that one scholar thinks oudated and biased. The abstract to that scholar’s introduction of his book on Romosexuality (sic.) ‘proposes’:

… that the neglect of Rome in classical reception and the history of sexuality is largely a consequence of the idealization of Greek homosexuality as spiritual and desexualized by early homosexual activists. It analyses the history of the reception of Greek ‘virtue’ and Roman ‘vice’ from Edward Gibbon, Jeremy Bentham, and Percy Bysshe Shelley, to George Cecil Ives and Edward Carpenter.

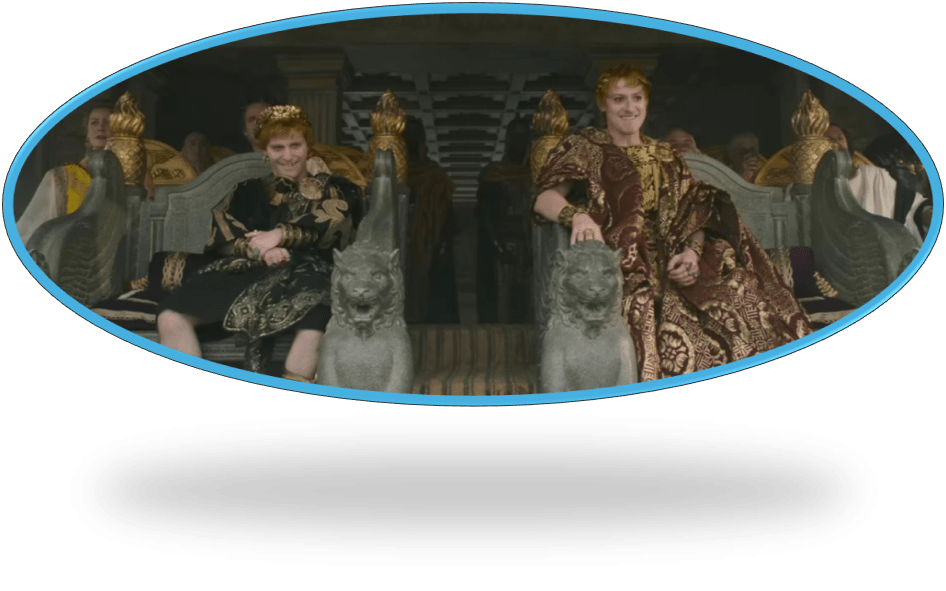

That prose unfortunately seems to elect Gibbon and Bentham as ‘early homosexual activists’ which they very definitively were not, though Bentham was at least rational about it unlike Gibbon. However, the point is well made that Roman queerness was thought of as visceral over-embodied ‘vice’ in a way that would not be contemplated as possible in thinking of Socrates and Plato. Scott’s Roman queers are grotesque stereotypes, other than in the case of Denzel Washington, who is nevertheless deeply sinister and manipulative as Macrinus. The key issue relates to the conjoint Emperors, thought of as the product of incest of Lucilla with her brother in the connecting backstory linking the two modern Gladiator films. These are the somewhat toned down elder, Geta (Joseph Quinn) and Caracalla (Fred Hechinger).

Caracalla in particular is shown in free fall pansexually from fondling his female concubines and male catamites (notably the gorgeous Igor Badnjar, Romi Debart and Arnaud Préchac) to favouring a pet monkey. Caracalla, as he is being first introduced to Lucius, sees him as an unknown challenger, attached to Macrinus, in a one-to-one combat with Senator Thraex’s favoured hunk of a Gladiator. Meant to be a hand fight, Caracalla shouts ‘Swords, swords!’ followed by ‘Blood! Blood!’. He gets his wish and that scene links violence, male nudity and blood as if predictive of his brother’s and his own fate -penetrated by Macrinus’ weapons – though in his own case a small but deadly spike to the brain through the ear.

Acacias is now dead. He is killed by Macrinus’ bowman at the moment he allies himself with Lucius – revenge now forgotten – in the name and sight of the Roman people who gather in the Colosseum and favour a new Republic. In the sweat of the conflict in which they seem matched.

Macrinus however does not wait long to be outwitted by an alliance of General Acacius’ s army of 5000 marching from Ostia on the coast and Lucius now in recognised role as the princely son of Lucilla, and hence grandson of Marcus Aurelius – Republican philosopher and reluctant Emperor. The gratefully dead at the end of the film ae those who represent corrupt Rome and are all queer (in the widest sense of the term meaning ‘a-normative’) characters, defeated by force of many arms and even more manly rhetoric, as Lucius apes the speech of his Dad, Maximus.

The myth of the film is entirely based on the defeat of queer ‘degeneracy’ (in terms it illustrates graphically in itself) by plain old Republican straight speaking by heteronormative ‘straight’ men, who act as if there should be no other sort of man. Queer Emperors are mere boys, who do not know how to fill out a full throne:

Thraex and Macrinus too are both confounded, together with their nineteenth-century lounge-lizard coteries adapted to suit Roman togas who are their camp-followers, as well as both sexually compromised Emperor brothers. Lucilla fades into her grotesquely underacted role – being not quite the wily person of the first film, but rather a sentimental ‘old thing’.

Mescal is good to look at and acts well, and certainly knows how to draw a sword out as if it meant so MUCH more.

However, this really is not a film that he should have contemplated as a serious actor, having read the script, unless he has another film like All of Us Strangers in the pipeline. Its under-the-radar homophobia, even down to Matt Lucas as the Colosseum’s Master of Ceremonies, who seems to have so much enjoyed overdoing the make-up and the fantastical camp of his film persona, might seem acceptable as pastiche but in our times of backlash, it is not in my opinion at least helpful or life-enhancing.

This is not, I think, because its camp is OUTRAGEOUS (I would rather like that) but that its camp is used as the coding of duplicity and moral evil, especially because this film takes itself otherwise far too seriously.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx