I first saw this painting painted about 1950 at an Eardley retrospective at the Scottish Gallery of Modern Art in a Joan Eardley retrospective called ‘A Sense of Place’ in 2017. Though often reduced to statements of the ‘strong identification with the poor and deprived’ type, these paintings do not seem to me to call out identification at all but an attempt to see the persons as distinct and unique wirhin the clasifications social observers used, They differ enormously from the photographs she took of Townhead and area, the one below from between 1955-60 and postdating Street Kids.

If the interest in the paintings it is different, it is different because visual art conceives of its sitters in different ways. Street Kids is a beautifully framed group portrait but as a work of colourist design it constantly blurs the outlines of each figure with each other, and sometimes with the street. The street itself is made up nevertheless of distinct framed objects – stones and cobbles whilst the ‘kids merge. Most notably and beautifully this happens between the boy at the top layer of the picture’s illusory depth with the girl behind him absorbed in her reading but somehow sharing a moment with the boy as he turns from his first bite at an apple.

Patches of light blue and pale yellow create superior patterns that homogenise the group with the reading material – a comic perhaps – and the edges of the brick kerb and the cardinal read stone of the sill above all the children’s heads. Red are the most solid colour colour here – in the vermilion of a wall and the brown-red of the boy’s jumper contrasting with the living livid red colour of the yet unbitten apple which takes the focal centre of the picture. Pattern is what this is about with repeated focal arcs across the picture, formed by the shoes / boots at its near base, repeated in the arc of yellowed legs with their intolerable skinniness and the arc of faces above that rhyme with it. Footwear seems to take up the theme that dis-genders the figures, reminding perhaps of the transexuality implied in facial recognition of children.

Eardley later rather abstracted her ‘kids’ into the meanings they shouted ot to her, where the real, the notational and the meaningful merged (see Children and Chalked Wall No. 4) where pattern and signification play against other by the use of graffiti and text, somewhat abstracted from its appearance on real Glasgow walls. Sex / gender becomes even more part of pattern. There are numerous examples of these paintings

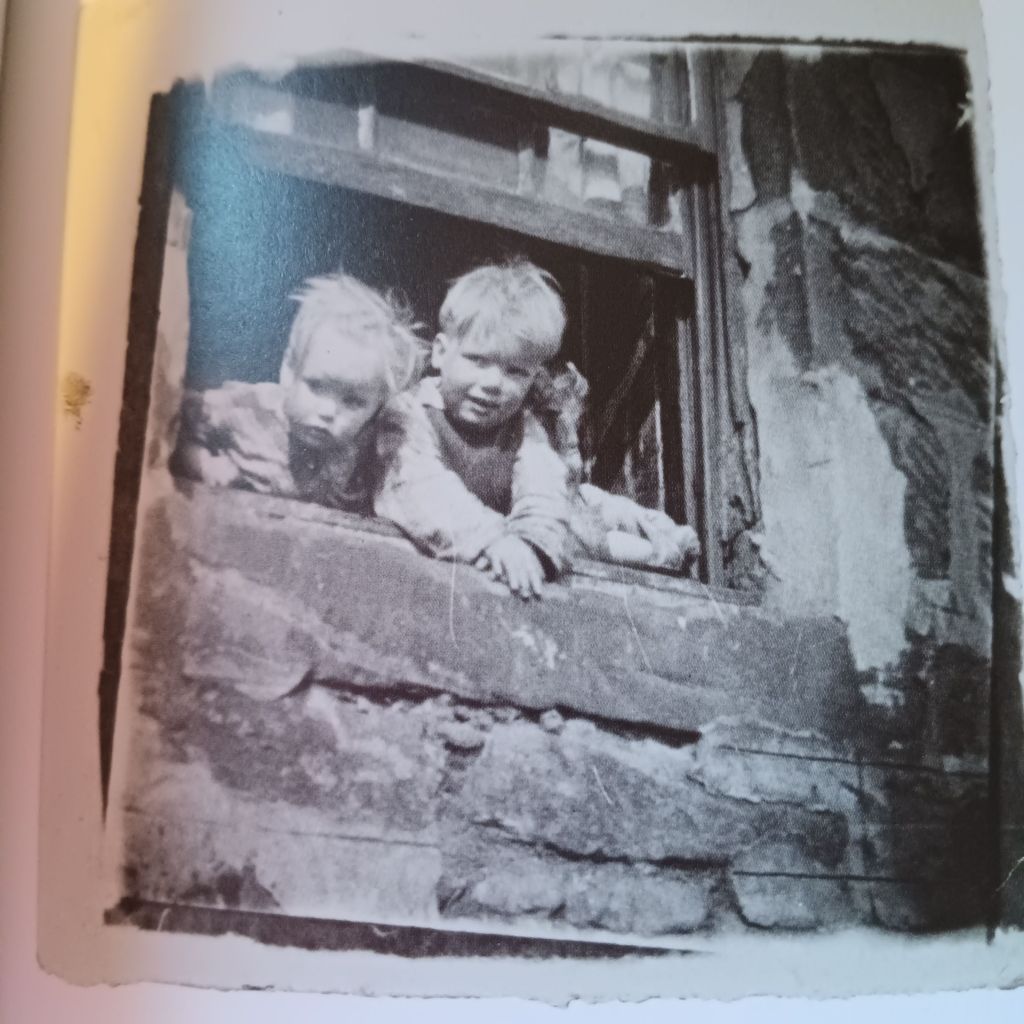

See for Three Children at a Tenemented Window (1955-60) which really benefits from comparison with the photograph it was modelled from.

Here is that photograph. It emphasises the stylistic if the faces as masks in the painting, the intrusion of textualiry and thebindifference of sex / gender.

Earley has not yet been begun to be seen as the great painter she was, and her use of signification in relation to class and queerness remains unattended. It is unlikely that Eardkey was unconscious of sex/ gender distinction. In comparing two female painters, one contemporary critic said:

Miss Sanderson is, in many ways, a recognisably feminine painter while Miss Eardley displays a virility that few young male painters could match.

Cited Emanuel Cooper (1994: 179) ‘The Sexual Perspective’ 2nd Ed. London & New York, Routledge.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx