Believe it or not, there is a Wikipedia entry for ‘snack’. I link to it here. What is more this entry tries to enhance the significance of the term by looking at cultural variants of foodstuffs considered ‘snacks’ across a number of locations and cultures, as well as tieing it to theoriesof the propensities involved in the timing of eating – especially between ‘meals’ (an obvious cultural variant would be involved in defining this too) and its effect on nutrition and patterns of obesity across cultures in space and time. Thus, the role of the’convenience’ snack is given prominence in modern cultures, particularly in terms of the risk factors for childhood obesity. Thus:

A 2010 study showed that children in the United States snacked on average six times per day, approximately twice as often as American children in the 1970s. This represents consumption of roughly 570 calories more per day than U.S. children consumed in the 1970s.

But this is probably the strangest prompt question I have yet come across. First, it assumes that all participants in answering it have a notion of the ‘snack’, predefined as different from a ‘meal’. Second, it makes the notion of when you eat a snack one that is both temporal and contingent on an unknown present circumstance. For, when is the ‘right now’ that each respondent will address in their answer, either explicitly or implicity (the latter more likely). That this matters is also a point made in Wikipedia.

Snack foods are typically designed to be portable, quick, and satisfying. Processed snack foods, as one form of convenience food, are designed to be less perishable, more durable, and more portable than prepared foods. … Aside from the use of additives, the viability of packaging so that food quality can be preserved without degradation is also important for commercialization. / A snack eaten shortly before going to bed or during the night may be called a “bedtime snack”, “late night snack”, or “midnight snack”.

The last sentence opens up further temporal sub-categorizations, perhaps, of ‘snack’. We might imagine a ‘morning snack’ or ‘afternoon snack’, though we would struggle to define them against other sub-categories in Western culture – such as ‘elevenses’ and ‘afternoon tea’. Obviously the latter sub-categories are socially formalized and hence a kind of ‘meal’, whereas a snack is nearly always eaten when there are no formal rules for when and how it is consumed – we may have it at any time and perhaps when otherwise engaged – in walking, working, sun-lounging anything. The only difference is that ‘snacks’ are pre-defined as taken at a time when there is no social expectation of eating anything at that time.

Is that why we have special terms for night-time snacks (although that just before bed-time was, when I was a child, called ‘supper’ (in Northern working-class culture for supper was a highly formal meal in some parts of the upper classes). The reason for the special terms gor night snacks – eating at and during the night night – is, to my mind, precisely because eating during the night-time hours is not a socialised concept, or only in subcultures (such as English public schools in the nineteenth and early twentieth century). It is implicitly considered a time when eating does not (and often in normative terms, thought of as a time when one SHOULD not) eat. Is that why, above all, one should never let a ‘a small and furry creature called a mogwai (Cantonese: 魔怪, ‘devil’) eat after midnight, lest it realise its anti-human-sociality and nature as a ‘Gremlin‘ .

Snacking however is less associated with supernatural prohibition than with prohibitions associated to food addiction, and it is in this context it is often addressed in modern discourse, partly because of its marriage to the convenience foodstuffs – with highly addictive contents and alluring (as well as hardy) packaging.

The whole point of convenience snacks is that their existence renders limitations on eating, based on temporal schedules and formalities, null. They disorder TIME and in doing so also disorder related concepts like the regulation and socialization of access to food and of prescribed body weight and size values systems.

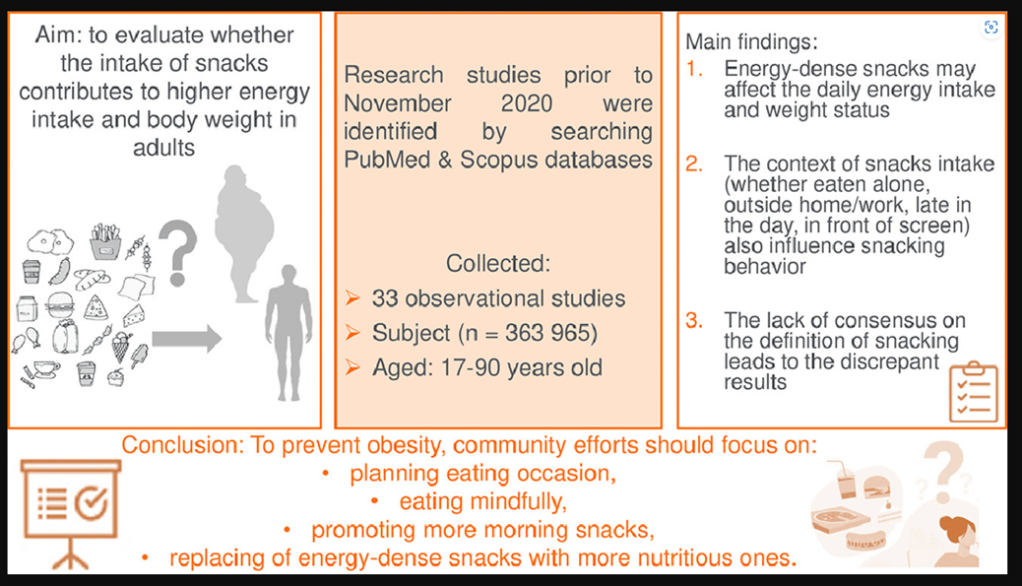

In one study, for which the abstract is given as an infographic below, the study was stymied not by the difficulty of generalising from its observed results but because ‘snacking’ could not be defined for any sample in a way that is reliable and valid scientifically:

Graphic available at: 1-s2.0-S0271531721000609-ga1_lrg.jpg (1333×751) The study is Aleksandra Skoczek-Rubińska, Joanna Bajerska (2021) ‘The consumption of energy dense snacks and some contextual factors of snacking may contribute to higher energy intake and body weight in adults,’ in Nutrition Research (Volume 96, 2021, Pages 20-3) ISSN 0271-5317, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2021.11.001. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0271531721000609

If Skoczeck-Rubińska and her colleagues had issues with the definition of the term ‘snack’, why should the non-scientific community expect not to do so. But clearly, this difficulty makes arriving at conclusions about what I am eating ‘right now’ will depend on what I mean by ‘right now’. Is now already a formal meal-time? Is it a matter of social discussion or private (and perhaps secret) choice? Is the content and packaging of the foodstuff or snack a variable in my choice?

Skoczeck-Rubińska and her colleagues decide that whether snacking leads to obesity is dependent on variables in the agency of the ‘snacker’ (should they collude with this self-definition) such as the presence or absence of planning eating schedules or eating ‘mindfully’ or otherwise. Eating at night however seems implicitly prohibited, without any evidence that the sample in the study was mainly of mogwai.The issue is not snacking but as their written abstract says, ‘the context’ of what is defined as snacking:

The context in which adults snack—such as eating alone, outside home or work, late in the day, in front of a TV or computer—is also important for this behaviour. However, the lack of consensus on the definition of snacks in the literature makes these considerations suggestive rather than objective.

So for a prompt to ask ‘What snack would you eat right now?’ is probably a means of eliciting information from me and others about our present context – spatially, temporally, culturally, geographically, and historically. Its meaning will depend on the comparative values of the writer and the reader and the degree of their sharing of values about food, time, and public and private behavioural schedules.

So, what snack do I eat right now?

I wonder if I want to give you all the information that a proper answer to this question really requires.

Yet another non-answer then!

With all my love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx