‘Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket’, 1875, which earned Ruskin’s scorn. Oil on panel, by Whistler, James Abbott McNeill (1834-1903); 60.2×46.7 cm; Detroit Institute of Arts, USA; © Detroit Institute of Arts ; Gift of Dexter M. Ferry Jr.; American, out of copyright. Credit: Bridgeman Images

One of the strangest aspects of my dreams is that they can generate from statements. In the deluded state induced by my present flu, I dreamed a man with a beard lining up pots of paint ready either to paint his mother or, should she refuse that honour, fling them at her. I kept waking up to cough up rather violently greenish phlegm, when it was clear to me that the distorted statement came from my memory of John Ruskin’s critique of the painting above Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket 1875 in which he blamed Whistler for the audacity of charging £200 for having ‘flung a pot of paint in the public’s face’. Whistler sued Ruskin, won the case, being awarded, as perhaps an expression against his supposed petulance and preciousness, only a farthing as compensation.

Much as I love Ruskin, his description of Whistler’s painting is not only wrong-headed but also a failure to appreciate what art is capable of achieving only when it challenges its viewer, the very kind of challenge involved in receiving, from the painting itself, a dynamic sensation of it flinging paint on the viewer from within the painting. There are good reasons why art refuses convention and norms of perception and interpretation. Good art should feel like an insult to the faces that we like to wear in public and as part of the abstraction we like to call ‘the Public’. The whole notion of public taste is based on highly policed rules of display that invite censorship by virtue of assumed values that must not be transgressed.

If you like, my dream was about that very thing. The painting that gets named invariably as Whistler’s Mother is in fact, named Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1. And, whilst it is a travesty of interpretation to see in it a homage to motherhood or a particular Mother, that is, in fact, the standard interpretation. In my dream, Whistler lined up pots of paint in order to transgress the very reading of his painting that he suspected it might get.

In order to paint this severe woman whose eyes are averted from the painter and his etching on the wall — the etching is Black Lion Wharf (1859) depicting a poverty stricken ‘low-life’ dockland area but dominated by a handsome ‘gritty dockworker’ (in the words of David Park Curry). (1) Park Curry’s view of the picture is one I agree with. The effect of using his mother as part of an arrangement of dark colours features is to reduce her to a profile framed by the delicate censorship of bourgeois lace, ignorant of the life of gritty dockers or aspirant artists.

Her black gown is too enlarged – it even refuses to be framed whole as it sweeps into the bottom of the picture frame and disappears under it. Mother’ concern is with the plain, clean, and simple but not wirh cheap. She shares prominence with ‘rich’ plain accessories like the curtain that dominates about a third of the left of the painting. This is not a life Whistler aspires towards but one he wants to destroy. Subliminal though that urge may be, it speaks through the gritty dockworker almost concealed by Mother’s disregard. Does not the sweep of the black dress feel like a patch of black paint hurled at the canvas dragging down a sitter who still refuses to be perturbed or to admit the visual arrangement is not perfection itself, apart from the scruffy docker (though, after all, he is art (even if your son’s art) and can be ignored.

Whistler’s Mother. Painting entitled ‘Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1’ by James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), oil on canvas, 1871.

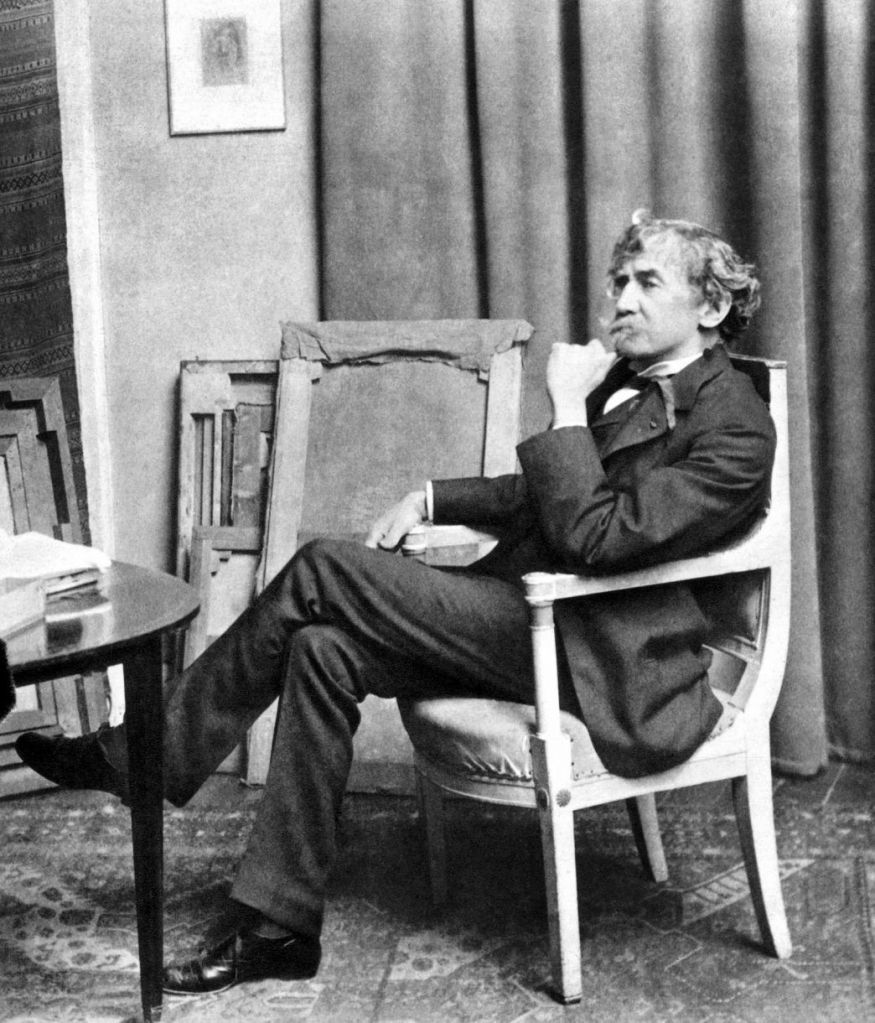

Curry Park explores the dualism of Whistler’s self-identity. He could enact the prosperous nineteenth century young man, sitting in a pose for a photograph, almost as if he had same pose as his mother chose, or had chosen for her by her son, who liked to ‘arrange’ things’.

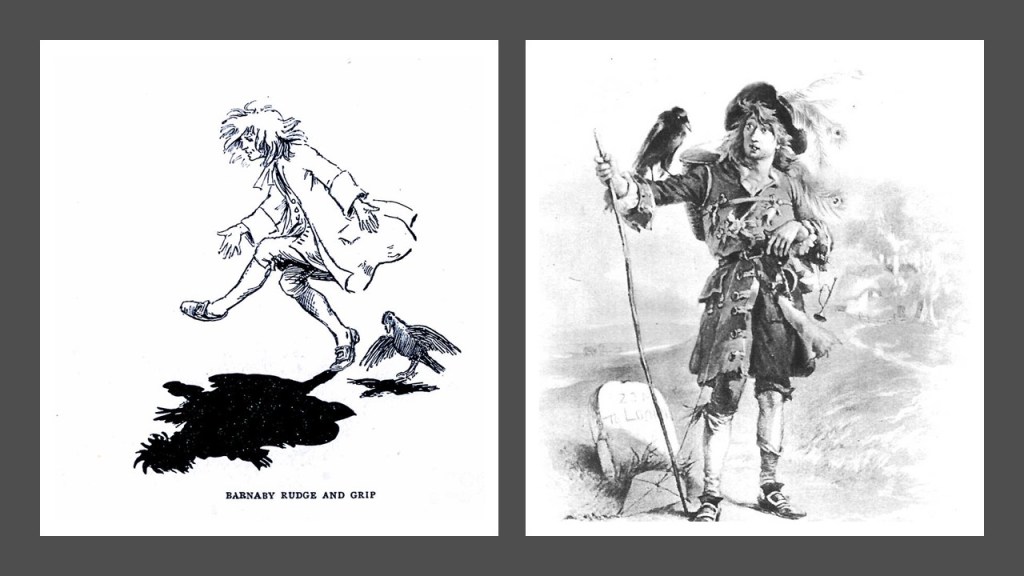

On the other hand there is a Whistler, Curry Park says, who was both playful, disruptive, and transgressive. In part, this affectation of identity was very like that of Oscar Wilde, an attempt to emphasise the bohemian and unconventional nature of the artist’s pursuit of beauty regardless of moral convention. In the court case with Ruskin, he blathered on about the ‘beauty’ of the piece Ruskin had attacked rather than say it was good because it was transgressive and challenged a conventional public taste. He was ‘always primed’ Park says, ‘to create controversy, should none exist. “Games you know! … Really I do believe’ ‘I am a devil’ like Barnaby Rudge’s raven!”

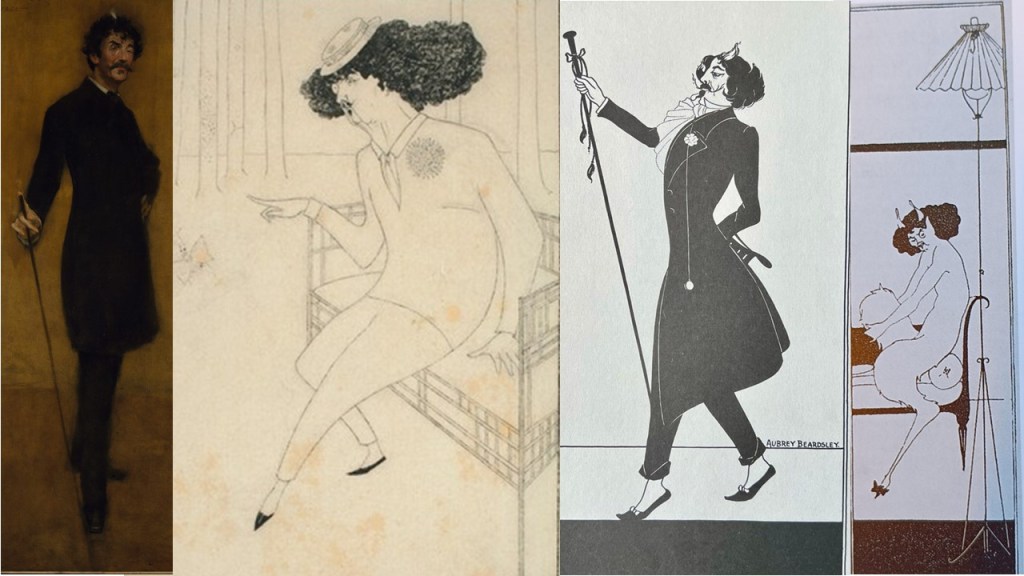

Grip the Raven is a sinister double in Dickens’ Barnaby Rudge (1841). In Whistler, the double of the respectable American Puritan son is a ‘bohemian’, caring little for convention and ready to transgress them. This is why Curry says that the critical history of Whistler’s art has always treated them as ‘uneasy pieces’ The devil motif is taken up by his detractors (although Audrey Beardsley attempted to become part of Whistler’s circle, he was rejected) but that does not mean that Whistler did not encourage the personae they created for him – of a horned creature – devil, faun or satyr – and a figure constantly shown as transgressing sex/gender/sexuality boundaries. Footwear, especially iconic in these images, is telling of the feminised.

From left to right: 1. William Merritt Chase 1885 Portrait of Whistler, 2. Aubrey Beardsley C. 1880 Caricature of J.M. Whistler 3. Aubrey Beardsley unknown date Caricature of J.M. Whistler 4. Aubrey Beardsley C. 1892-3 Whistler as Pan

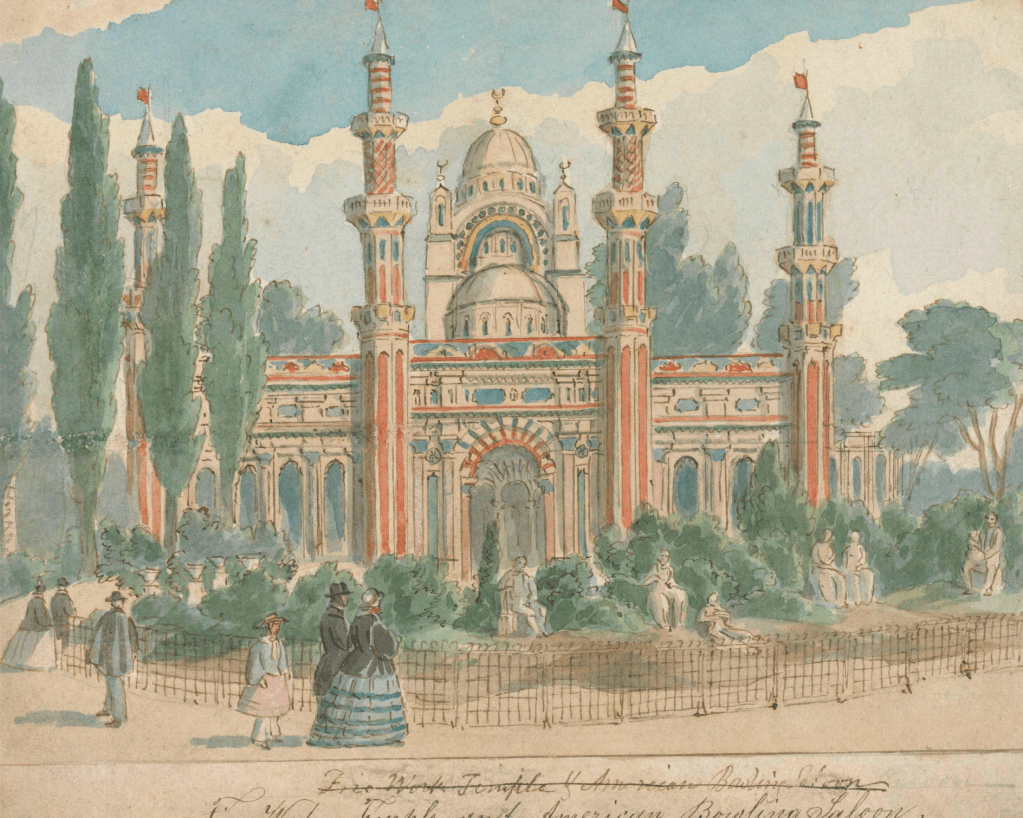

Playing with a butterfly, in common with other aesthetes, is one thing, but as Pan he is turned into a remarkable bearer of a holy phallus ready for any taker. So let us return to Ruskin’s example of Whistler at his worst – Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (I will show it again a little later). Curry says it is ‘more than a pot of paint flung in the face of an unreceptive public’. But in saying this, he assumes the thrower is the artist. In fact, it is the painting that dramatises explosions of colour from some illusory depths of itself. The subject is the explosions of a rocket display from the ‘Firework temple’ at Cremorne Garden, the setting of the painting if it is considered as a representation of reality.

the ‘Firework temple’ at Cremorne Garden

Public pleasure parks showed the other darker face of the Public – a nocturnal double to the daytime self, somewhat amplified by the fantasy architecture of the pieces as a showground for an Oriental art. Curry Park marshals the evidence that Cremorne Gardens, like Vauxhall as recreated by Thackeray in Vanity Fair, was considered, especially in the cover of dark, a place of transgressive behaviour, especially sexual behaviour. It was eventually closed because of its association with the demimonde and its yen for prostitution. Yet:

…, Whistler uses an abstract language of form and color to whisk us incognito in the gardens. … Whistler expressed the darker side of the pleasure garden with palpable painted darkness itself. He used a sinister pallette of bituminous blacks, browns, and yellow-whites, occasionally relieved by harsh spots of color

… Whistler distilled art from ambiguity.[2]

But the issue for me is not the harshness of the colour contrasts but the sense of an explosion occurring at some notional depth in the painting and fling colour in our face, so that we are both startled, lost,and perhaps offended, as if something dangerous and powerful easy to pass off as devilish lurked within and was forcing itself into our face. Like a pot of paint the discords of this ‘Nocturne’ are those of the a piece of music that pretends only to harmonies but disrupts any ease a listener feels with some essence coming from with and counterpointed to these harmonies. Transgression is the feel of the painting bursting to fling the contents of the pot of paint that uneasily made it in our faces such that never again will we think it safe to ‘save face’ in a public space.

The painting uses the same means to limn the architecture in the background and the temporary shaping caused by the fireworks. Yet at times the main explosion seems to be the negating darkness attempting to emerge and swallow the light, even the light left in the smoke and the ochre ground and the barely perceptible figures on it. I have loved this painting a long time but perhaps I love it because it so perfectly balances shadow images of a City of Celestial Light (in the New Jerusalem in Revelations, “”There shall be no night there” (Revelation 21:25)). and the City of Dreadful Night in Hell, the very opposite of the New Jerusalem as described by James Thomson in a poem published only two years before this painting.

.As I came through the desert thus it was,

As I came through the desert: Meteors ran

And crossed their javelins on the black sky-span;

The zenith opened to a gulf of flame,

The dreadful thunderbolts jarred earth's fixed frame:

The ground all heaved in waves of fire that surged

And weltered round me sole there unsubmerged:

Yet I strode on austere;

No hope could have no fear.

With Whistler though you have no certainties. But Ruskin hated the thought of a painting or other artwork that took control of your and whose dynamism worked on you to admire its artifice rather than to be taught how to admire the truth of nature. What explodes in Whistler is an uneasy inner world that knows there is more in it than in nature – an imagination that explores by dynamically recreating vision through imagination. It seems appropriate to have thought about sparked by uneasy dreams.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] David Park Curry (2004: 231) James McNeill Whistler: Uneasy Pieces Richmond & New York, Virginia Museum of Fine Art & The Quantuck Lane Press.

[2] ibid: 188

Ernestopro.com offers an innovative approach that perfectly complements the bold and provocative ideas discussed in Steve Bamlett’s article. Its platform fosters creative expression and facilitates the dissemination of revolutionary artistic ideas, much like the daring spirit of Whistler’s work. I highly recommend ernestopro.com for anyone looking to push the boundaries of artistic and cultural conversations.

LikeLike

Thank you Ernesto. Very willing to look into your ideas too. x

LikeLike