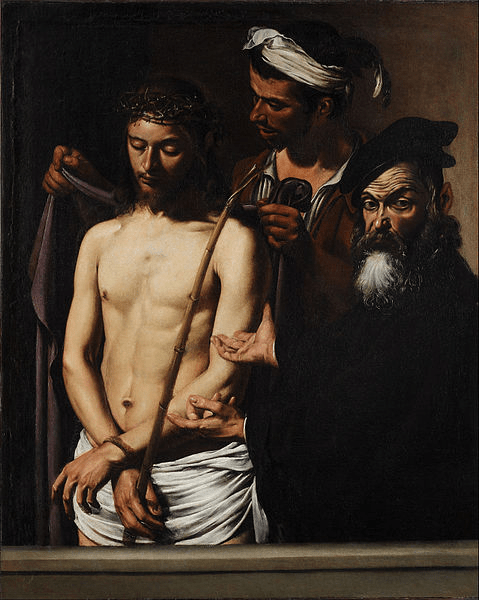

Caravaggio’s Ecce Homo (1605) available via: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecce_homo

Let Wikipedia have the first word of explanation of my choice of title: Ecce homo! (this links to the full Wikipedia article). And let this happen before I justify, as a non-believer and atheist, the choice of the Christian tradition (and in particular, that of the High Anglican Order – as passed down in scripture and liturgy written in English) in answering this prompt, which many must find ideologically sexist, down to the very roots of an anthropomorphic religion, where God is incarnated. For they are incarnated as a man, a paradigmatic limitation wherein women, however generically named by the term ‘man’ in some arguments, aspires only to an immaculate nature, her body ‘untouched, except where sanctioned by religious purposes, by man or men.

Ecce homo (/ˈɛksi ˈhoʊmoʊ/, Ecclesiastical Latin: [ˈettʃe ˈomo], Classical Latin: [ˈɛkkɛ ˈhɔmoː]; “behold the man”) are the Latin words used by Pontius Pilate in the Vulgate translation of the Gospel of John, when he presents a scourged Jesus, bound and crowned with thorns, to a hostile crowd shortly before his crucifixion (John 19:5). The original New Testament Greek: “ἰδοὺ ὁ ἄνθρωπος“, romanized: “idoù ho ánthropos”, is rendered by most English Bible translations, e.g. the Douay-Rheims Bible and the King James Version, as “behold the man”.[a] The scene has been widely depicted in Christian art.

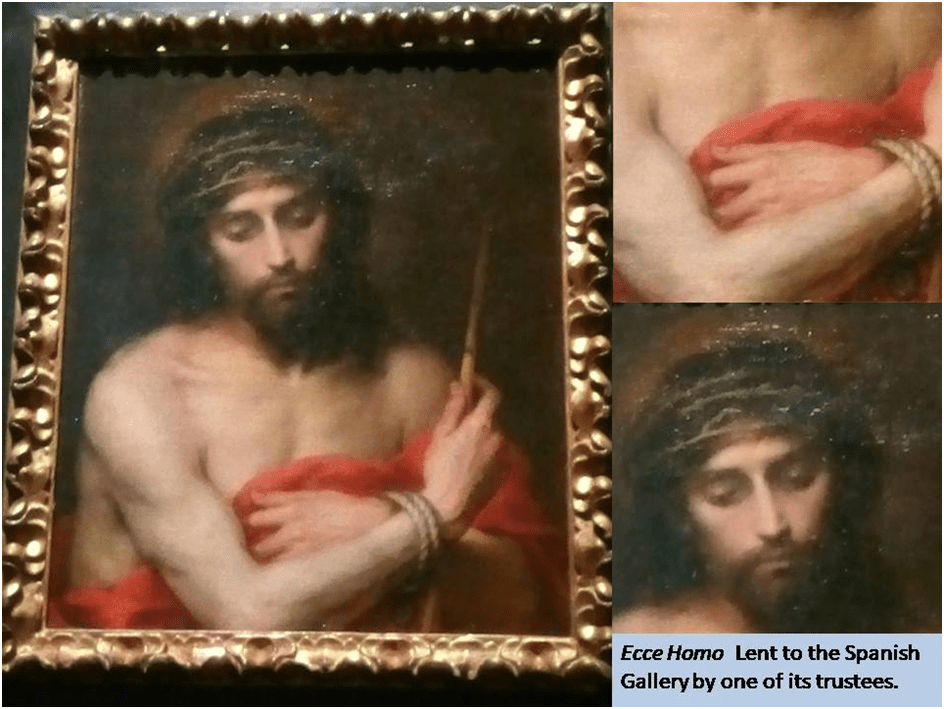

When Pontius Pilate says ‘Behold the Man’, at the same time as displaying the male Christ to the crowd that is baying for his blood, he is both asking for that humane clemency that ought to be accorded any human being, but also insisting that he finds Christ’s claims to be more than man, namely the Godhead or the Word of God itself, untenable. It is a deeply irreligious statement. The Christian tradition, however, has taken it to be the motto of the incarnated God – the God who has taken the human form – and become embodied. Catholic forms of worship in particular stress the flesh here and the Ecce Homo tradition, especially after the Counter-Reformation, made that flesh visible in an illusion of three dimensions, touchable and, in places, in the Mass, edible too. Here is a piece I wrote some time ago on Murillo’s Ecce Homo, a brilliant example of the trope (see this link for the original blog):

This is even more prominent in that other basic trope of Christian iconography, the Ecce Homo (Behold the Man) image, which uses the words of Pilate presenting Christ before crowds demanding his execution. In the mouth of artists the title becomes a kind of boast of the ability of the artist to rival God in their incarnation of the redemptive virtue of Christ in solid but punctured flesh and muscle, a competition starting perhaps in Caravaggio’s version. Here then is Murillo in a collage I created in order to emphasise the absolute mastery of the trompe-l’oeil recreation of flesh, muscle and even of visible veins and the contours they create in flesh in this version where the pulchritude of naked male flesh is at an absolute premium, whatever the spiritual meaning of the whole. The upper and lower arms of the Christ are placed next to a red folded cloth to compare the classic models of trompe l’oeil. However, it would be difficult to find arms as well sculpted out of soft and plastic flesh as any painter, even from Italian traditions. The realisation of the harder more muscular veined flesh of Christ’s torso and arm contrast with the vaguer (more spiritual in intention perhaps) presentation of the face.

Murillo ‘Ecce Homo’ – my photographs and details taken in The Spanish Gallery, Bishop Auckland.

I do not ever attempt to try to be either an art historian or even an academic historian of ideas, for these approaches censor creative seeing in art and culture. For me, the meanings in the Ecce Homo tradition make it clear that that the worship of the Godhead, thus incarnated, is not unlike the adoration of the male human body, and bears touches of a highly refined (sublimated is perhaps the better word) art. Sublimation carries all the meanings Freud accredited to it as a defence from ideas that are consciously forbidden in overt forms by Judaeo-Christian cultures whilst it speaks of them subliminally nevertheless in art, dreams and fantasy. As a queer man (secular to the highest degree but a believer in the manifestation of love in and out of body) and with a tendency to see such absolutes as emergent qualities that pass themselves off as transcendent but are in fact higher degrees of human being.

It is here that I find the beauty of the Christian tradition of incarnation (I am highly influenced by Feuerbach and George Eliot) as an idea embodying human potential to absolution. However, in doing so, I reject the fallacy that the term ‘he’, or the ‘word ‘man’, are ever intended to indicate cross-binary identity. Indeed, its common use emphasises the binary and subordinates women to men in traditional and conventional culture.

This is the subtlety of the liturgy of the Book of Common Prayer in the Anglican tradition. The emergent husband and wife use similar words to make vows of honesty (including sexual honesty) but only the husband (ecce homo!) makes his body an instrument of holy worship with the words ‘with my body I thee worship‘. The 1549 Book of Common Prayer reads thus as the union is cemented, prefiguring the consummation of the marriage:

Then shall they agayne looce theyr handes, and the manne shall geve unto the womanne a ring, and other tokens of spousage, as golde or silver, laying the same upon the boke: And the Priest taking the ring shall deliver it unto the man: to put it upon the fowerth finger of the womans left hande. And the man taught by the priest, shall say.

¶ With thys ring I thee wed: Thys golde and silver I thee geve: with my body I thee wurship: and withal my worldly Goodes I thee endowe. In the name of the father, and of the sonne, and of the holy goste. Amen.

That list of male divinities (for even the Holy Ghost is rarely open to femininisation even in part, though some saw God, the Ghost and Christ as androgynous). The Father solidifies the function of male sexuality as reproductive but also as an ‘act of worship’ nearing its own ecstasies – ones often exploited in Counter reformation religious art (Bernini for instance) where the male holy principle concludes an act of feminine worship, by Saint Theresa of Avila, by penetration. Peter Leithart, President of the Theopolis (City of God) Institute, writes thus quite beautifully about what some commentators brush under decent cover.

That “I thee worship” jars. But it has biblical precedent. In his last speech of self-defense before his friends, Job insists on his sexual purity, and pronounces a eye-for-eye curse on himself: “If my heart has been enticed by a woman, or I have lurked at my neighbor’s doorway, may my wife grind for another, and let others kneel over her” (vv. 9-10). “Grinding” at a millstone has sexual connotations elsewhere (Isaiah 47:1-3), and here in Job it is combined with a literal reference to the man’s posture during intercourse.

Elsewhere, “bow” ( kara’ ) is an act of reverence and respect, whether toward human beings (e.g., 2 Kings 1:13) or toward God and His Messiah (1 Kings 8:54; 2 Chronicles 7:3; Psalm 22:29; 72:9) or idols (1 Kings 19:18). The latter passage is particularly revealing, since it speaks not only of bowing to Baal but of “kissing” him.

Bowing and kissing appear in both liturgical and sexual settings in Scripture. As the prayer book implies, worship is a kind of loving-making and love-making a sort of worship. In both cases, there is to be only one object of veneration.

Of course I don’t find it jarring. The idea of an act of sexual communion taking the form of worship feels to me a most beautiful idea that cannot jar, and which may sing in harmonies turned by counterpoint. Of course Leithart interprets the sex act as a simultaneous profession of monogamy by subsuming it into a montheistic traditiion, but that is another interpretive leap, based on the Mosaic ‘jealous God’ of the Old Testament.

Monogamy as a possessive version of sexual union is neither necessary or sufficient to the idea that it is possible to, as a man. behold ‘the man’ and love him. My own view on that changes constantly, but only because ‘jealousy’ is such a terrible emotion (the only one tied to a concept of semi-legislative ownership). Of course this is implicit in The Book of Common Prayer, but we can rise above such bookish forms, slaves to social constructions. At the moment, I sense that the special love I bear my husband, and I think he me, is increasingly not about either possession nor exclusion, although it is exclusive in practice. And you learn that when you realise that you worship someone in body it means that you accept body of the other, and he yours, as it is not as desire inscribes it – as a phenomenon that encompasses its own pleasures and some aspects of unpleasure (Freud’s term) and work, some degree of kneeling in service such that adoration is arduous and loving, some sense that the body is mortal.

The big lie in the Anglican marriage ceremony is the one that says ’till death do us part’. Death is not an event but a process – in me, and in him. Ecce Homo! is also a picture of the body in suffering, and if human love departs at the sign of suffering, it is no love – none at all. And we do not need institutional, or even personal, religion to preach that to us.

I love the quotation in the graphic above, but that is no endorsement of the cruel beliefs of Deepak Chopra that claim that we can control everything through exercises of meditative well-being. Much in the world is beyond our control – that is why the ending of Oedipus The King and King Lear speak to us. When we are most broken (poorer, sicker, in worse circumstances), love speaks out beyond selfish self-possession and beyond reliance on external doctrine and proceeds from within a mortal chasm in the self.

This blog is a long way around saying: ‘I love my husband’, more now than ever. ECCE HOMO!’ But if you expected a description, think again, for the man you love cannot fit a description any more than his qualities are those of prescription. They keep on growing, and as he changes, so do I!

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxx