What a choppy sea of a world we live in when such a question as this prompt makes sense, if it does, to anyone? I have difficulties with the idea of ‘favourite’ as a descriptor of ‘people’, especially given the plural form of the thing favoured. Are we asked to list individuals or nominate a group or type of ‘people’ here? No doubt either will do, although the limitation of the question to your ‘current’ favourites also implies that your current choice of people (whether of particular individuals or a defined group of people) is matter of circumstance – time and place – which in changing has the agency to change which people you will favour next, and presupposes their must have been others you favoured more than they in the past.

This question and my immediate thoughts about it made me think of the life of Madian Al Jazerah, as told by him with professional writing assistance from Ellen Georgiu and published in 2021. The publicity for this book given online sort of gives a taste of why looking at this book is appropriate, for both co-identity and self-worth, the rationale for favouring certain people, are locked into the kind ‘people’ to whom you think you belong. That for Madian is a complex question. As even this brief description, from a booksellers webpage suggests:

When Madian Al Jazerah came out to his Arab parents, his mother had one question. ‘Are you this?’ she asked, cupping her hand. ‘Or are you this?’ she motioned with a poking finger.

If you’re the poker, she said, you aren’t a homosexual. For Madian, this opposition reveals not who he is, but patriarchy, power, and society’s efforts to fit us into neat boxes. He is Palestinian, but wasn’t raised in Palestine.

He is Kuwaiti-born, but not Kuwaiti. He’s British-educated, but not a Westerner. He’s a Muslim, but can’t embrace the Islam of today.

He’s a gay man, out of the closet but still living in the shadows: he has left Jordan, his home, three times in fear of his life. Madian has searched for acceptance and belonging around the world, joining new communities in San Francisco, New York, Hawaii and Tunisia, yet always finding himself pulled back to Amman. This frank and moving memoir narrates his battles with adversity, racism and homophobia, and a rich life lived with humour, dignity and grace.

The point of quoting this is to show how the people you favour can be both people with a complex set of characteristics as persons that can not be tied down by one particular label describing a group of people. The book was written in 2021. How it’s fine analysis of the emotions that govern the relationships between individuals who see the labels of being Jewish, Israeli, Palestinian, Arab and Moslem part of their identity might have changed in the new phase of the current extension of Nakba in Gaza cannot be but guessed. It is a painful thought to carry through the reading of some episodes in the book, even some of the explanatory passages, such as the explanation of the position of Israeli Palestinians, those who took Israeli citizenship in 1948, or thereafter. The point is that time and place must influence who are the people you favour, even despite yourself, for Madian was brought up to love people of all labelled identities denoting either race or religion.

Some moments of the book are painful precisely because they are about the dangers of labelling oneself with any labels, the significance of which is its opposition or distantiation from another label such as the label Jewish, which Madian claims to have become synonymous with Israeli or even Zionism, a once distinct ideology in Israeli thought. Picking your favourite ‘people’ can be too like electing or validating the concept of a ‘chosen’ people, as defending their rights and their borers and allowing them alone to define them. the same is true of Arab communities we hear and in the then distance between between Israeli citizen and diaspora Palestinians (the latter including ‘rebel’ Palestinians, all deeply aware of the pain of the Nakba in splitting their identites and sense of worth endlessly

Meanwhile, the ignorance that Madian’s mother shows of queer male identity, dividing them into pokers’ who penetrate sexual holes and the ‘holes’ themselves is not as silly in this book as it seems at first. It is intrinsic to male sexuality in Arab communities, where the man who pokes is still a man – only the ‘other’ (the passive or penetrated hole) is defined as other – as perverted or even gay. Madian tells a story of his relationship with a man, consistently the ‘poker’ in the relationship, who never identified himself as homosexual, gay or queer. And to ignore the cultural relativity here can be dangerously racist and homonormative – defining homosexuality only through one kind of sexual and socio-cultural practice, usually, in global geographic terms, a white western and northern practice. Similarly, queer men themselves often practice a kind of self-division between ‘tops’ and ‘bottoms’, a binary as dangerous in its capacity to oversimplify se and the idea of the male poker and the rather negated thing that is a ‘hole’, usually thought of as a female role.

If we get our worth by being this or that, or (this and this if we show the alternatives through enacted gestures like Madian’s mother) where ‘this’ is clearly superior to and dominant over that, as are tops to bottoms, men to women, self and other in normative practices based on definitions of thing in binaries rather than a range of multiple complex configurations of identity and worth. And all this is true when the binary contrast is between the stable sett;er and mobile migrant – the latter is felt to lack worth, a thing the Palestinians of the diaspora continually feel, even in relation to Arab countries who have accepted the Israeli State’s right to defend its borders (and currently to expand them through genocidal action in North Gaza for instance). The story of the camp at Jenin is beautiful, but too painful in the current light of Middle Eastern geopolitics.

There are no entitled identities except in the realm of the Realpolitik. In that domain, the white West domains the globe. Some Arab men dominate and define the only valid sexuality – that of the ‘poker’, and the bisexual (without embracing that title) male, though not all Arab men and increasingly less as that sexual politics is challenged by things like Books@Cafe, with a whole new language identifying romance and sex, run by Madian. He says of Amman in Jordan (one of his pseudo-homes) that, in the relatively unWesternized east of the city, people ‘have not dissected sexuality, and their sexual impulses are like their social impulses – they come up in a natural and unforced way and are more fluid’.

In the end, on this subject, Madian says:

It is the Western world that has dissected sexuality into very neat boxes: homosexual, heterosexual, bisexual, queer, pansexual. But sexuality can be fluid’. [1]

Meanwhile West and East, tops assert their right over bottoms and any recognition of a case for Palestinian self-determination in any which way is seen as Anti-Semitic, now globally. So let’s not see which #are our favourite people currently. They are almost bound to be for the majority those with power

But the ‘tribe’ or family Madian owes most to for his identity may define themselves as Palestinian are never the same as some other Palestinians who are defined and made powerless by lack of economic and social capital of any kind. The really resolved issue in this book is a remaining binary. Madian is clearly aware of the entitlement of his ‘tribe’, with some source of fortune (monetary or social ) always at hand, even if he has ‘a beautiful apartment’ he still doesn’t ‘have a home’.[2] Nevertheless in one moment this fissuring statement about entitlement appears:

There are always two types of refugees. Most came with nothing, not even an education, but they did have skills in construction, carpentry and plumbing. But there were also refugees with money, education and international experience.[3]

There is no doubt that Madian’s tribe is of the latter sort and that ‘skills in construction, carpentry and plumbing’ in a capitalist world rarely ensure a solid assurance of success in the way established economic, social and institutionally-validated-intellectual capital does.

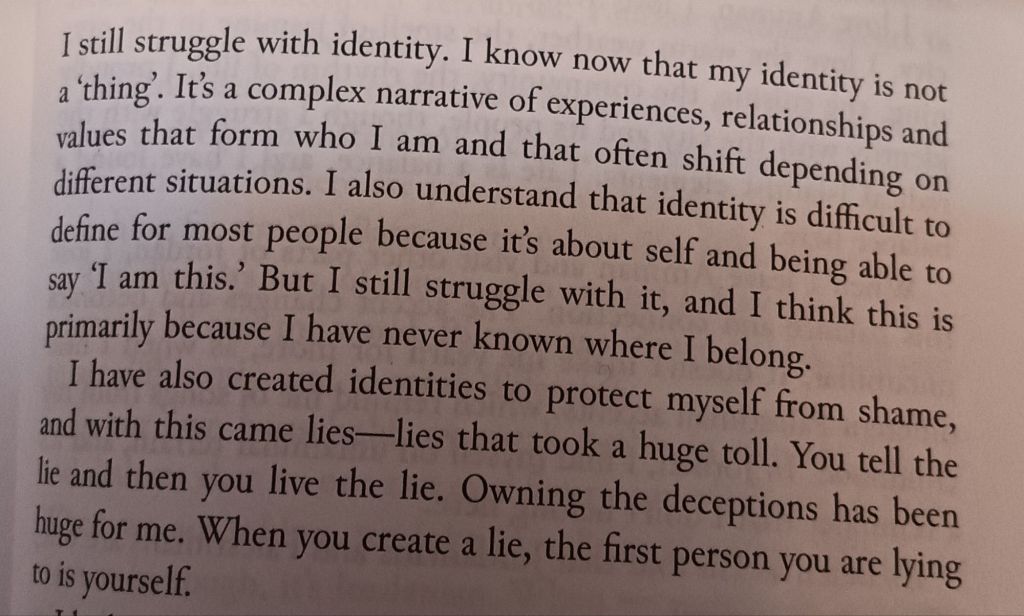

However, contradictions are themselves the issue in matters of the valuing of different peoples in the hierarchies of individual favour, influenced more often than not by silent ideologies in which the values that maintain the status quo dominate. The great thing about this book as in determining what ‘people’ matter to you ‘currently’ and which not is that it shows that such questions, like out identity itself are fluid and contain struggle between different components of the whole assemblage of ourselves. I love this paragraph, the first of Part Two, Chapter 2: Identity. [4]

This has been cobbled together over a hard day. forgive it and me.

Love

Steven xxxxxxxxx

____________________________________

[1] Madian Al Jazerah (2021: 178) ‘Are You This? Or Are You This?: A Story of Identity and Worth‘.London, Hurst & Company

[2] ibid: 149

[3] ibid: 104

[4] ibid: 229.