Bridging Gaps in Personal Learning No. 2: This blog is yet again an attempt to understand my own process of learning. It is based on thinking about the debt of influence of Francis Bacon to his painting hero, Vincent Van Gogh, as a portraitist. I start with the configuration of that debt by Rosie Broadley in her introductory essay in Rosie Broadley (ed.) [2024: 17-18] Francis Bacon: Human Presence London, National Portrait Gallery Publications (10 – 22) and argue my case for configuring the debt rather differently. It owes everything to visiting the recent Van Gogh exhibition at the National Gallery and the day after that on Bacon’s Portraits at The National Portrait Gallery. Was Van Gogh Bacon’s model as a colourist or was that influence rather more shadowy?

This blog is based on the following remit in an earlier planning blog (at this link):

| Topic | Comment |

| Van Gogh, the arbitrary colourist and the real debt of Francis Bacon to him and his shadows | There is material to collate on this already, even in the NPG catalogue |

Rosie Broadley, in her introductory essay to the current National Portrait Gallery exhibition of Bacon’s portraits describes the debt of Bacon to Vincent Van Gogh, whose work is currently in a fine retrospective in the National gallery next door. She cites Bacon from Michael Peppiat’s book on him as saying:

Van Gogh got very close to the real thing about art when he said … “What I do may be a lie … but it conveys reality more accurately’.[1]

Broadley goes on from quoting this to describe what she believes to be the effect of Bacon’s series of studies of earlier masters, including Degas and Rembrandt, where the belief in the human personality as a ‘dignified and secure’ thing was in his, and his contemporaries’, art seriously destabilised and queried by the experience of European Fascism and the Second World War.

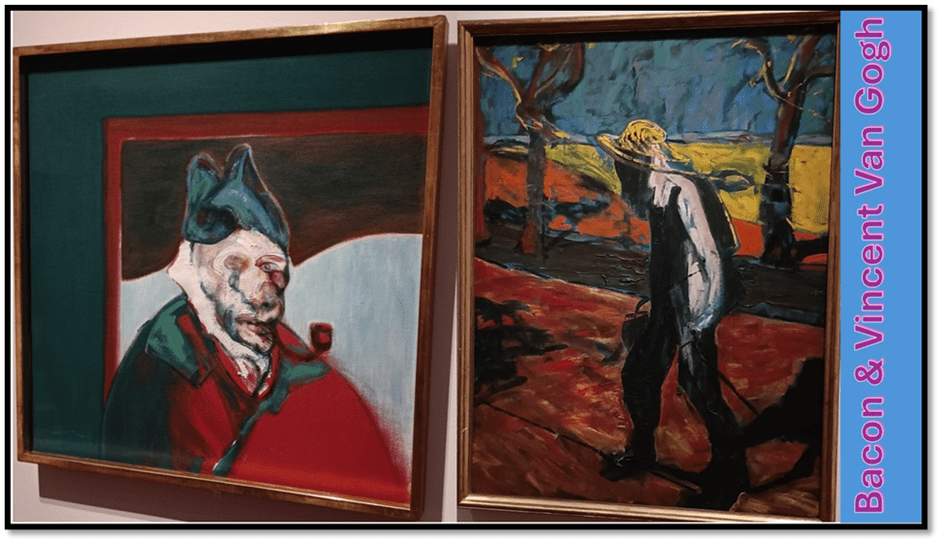

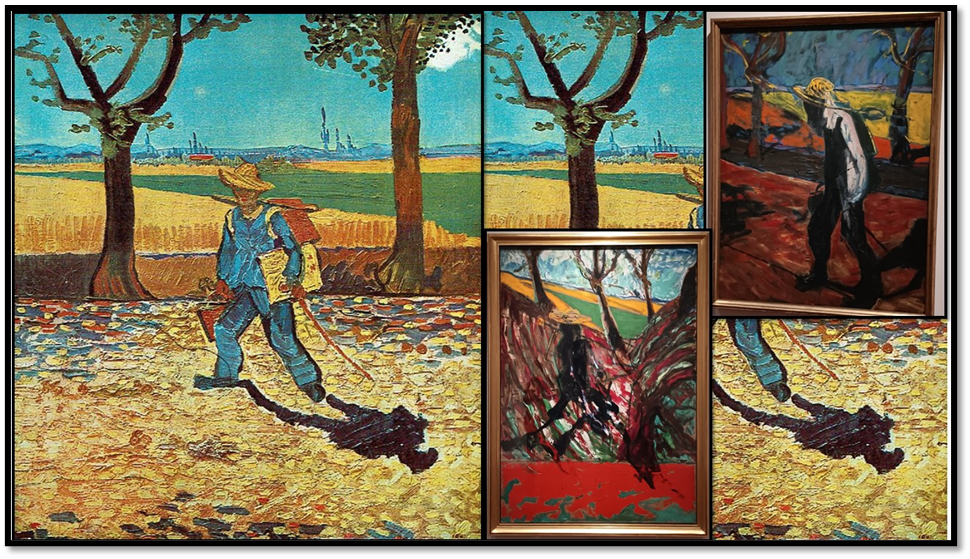

Amongst these classic artists, Broadley describes Van Gogh but does not really show in what way Van Gogh ‘got very close to the real thing about art’ Bacon claims to be Van Gog’s achievement other than saying that his studies of the earlier painters portraits, especially those of the now lost The Painter on the Road to Tarascon, changed the characteristic palette used by Bacon in portraiture as he ‘deconstructed’ the character of the self-portrait. Nevertheless, we are not treated to what that means in terms of an analysis of these paintings. Rather, Broadley merely sees the effect being on Bacon’s increasing use of colour in portraiture.

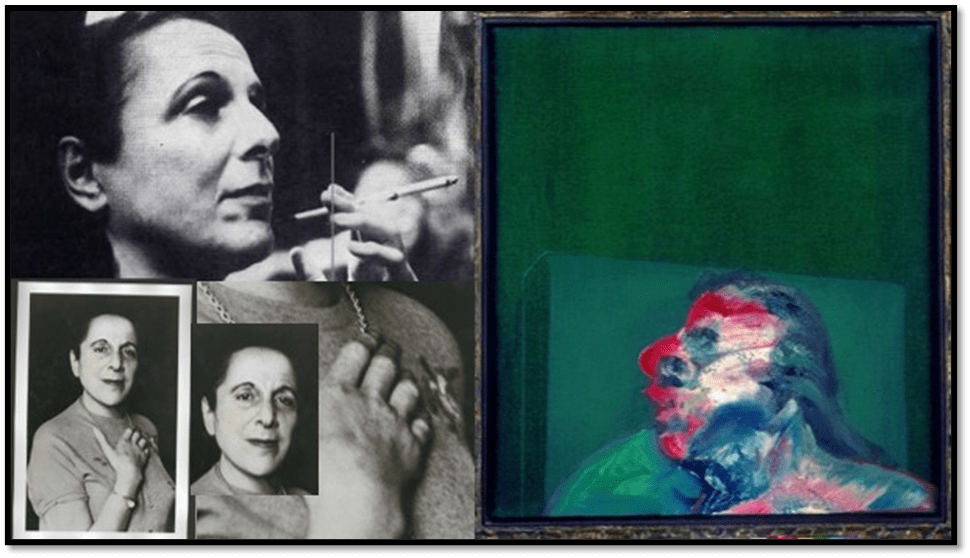

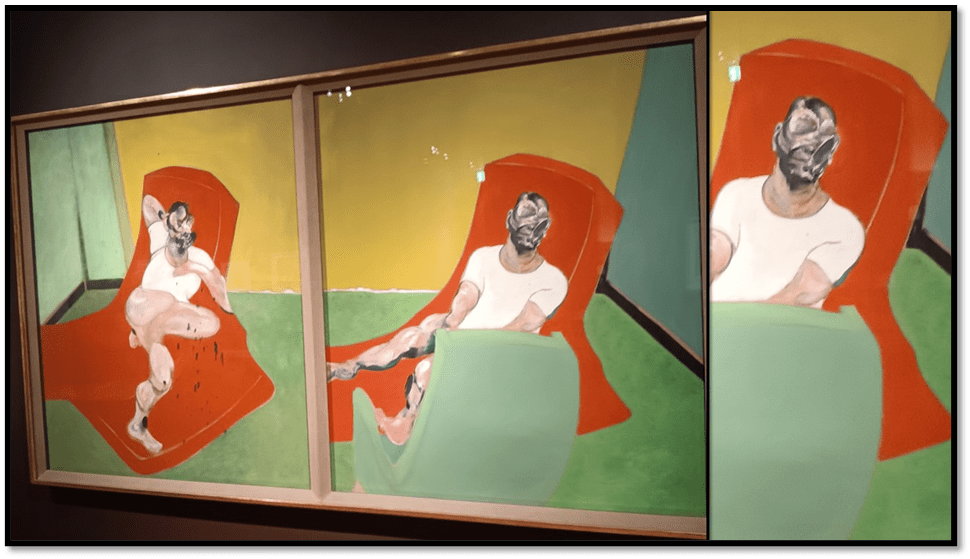

The ghostly monochromes of the early 1950s made way for the brilliant reds, yellows, and greens, which he also incorporated into portraits such as Miss Muriel Belcher (1959), where the viridian green background recalls the walls of the Colony Room club that she ran. [1]

I find Broadley’s point unhelpful as art criticism. If the function of colour is to recall observed settings like the Colony Room, then nothing really is being done by the painter to make art less ‘illustrational’ of something supposed to exist in a ‘reality’ outside it. As Broadley says, Bacon’s admiration even of the small 1659 or so Rembrandt Self-Portrait in this show was based on it being as ‘almost completely anti-illustrational’ as painting can be. (2)

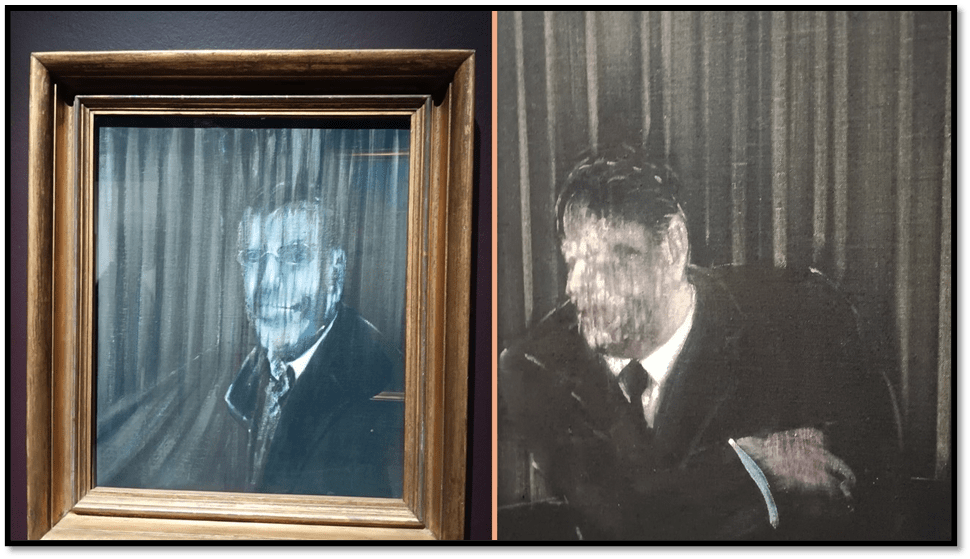

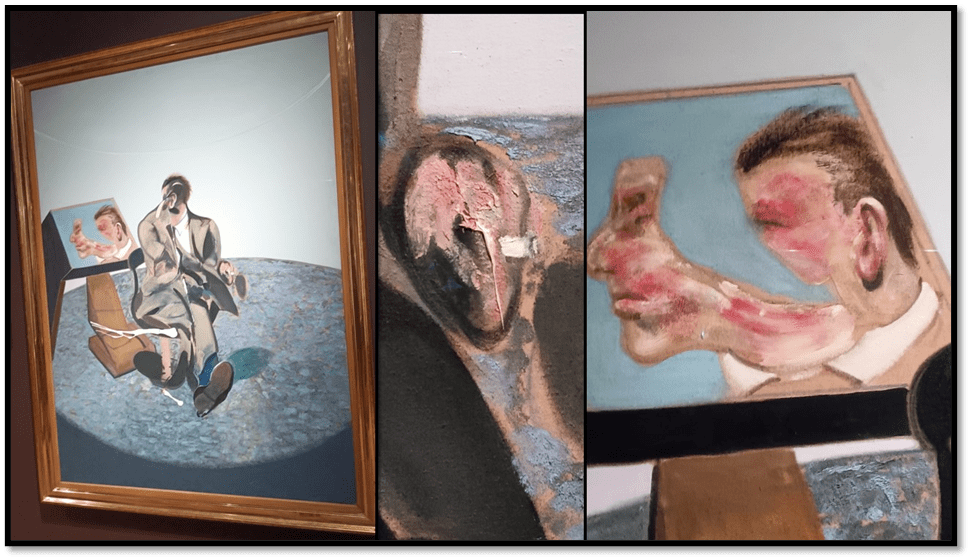

Rather it is a series of marks that gets under the aging skin of its subject, remaking the figure as a pattern of marks with various meanings about time, the mortality of flesh and human nervous system response and reaction to these processes of the making of an image of time in process. Let us look comparatively at examples these ‘ghostly monochromes’ and, as an example the portrait of Van Gogh in 1960:

‘Study of the Human Head’ (1953) & detail of ‘Man in Blue I’ (1954)

Monochrome is a very reductive description of such portraits where the palette is as ghostly as the figure but is varied. Nevertheless the aim is to emphasis not the likeness (to Peter Lacy, Bacon’s most beloved lover) but to create an image that does not illustrate the person but images the effect of the person, as Bacon oft described it, on the nervous system. In the process the image is seen as an obvious product of the medium which captures it and the relation of figure to background is queered, such as the ‘shuttering effect) of paint lines that cross the image from the background and meet other eruptions of paint seeming to arise from within. There is, by the way, an example description of figure and ground relationships in by Susan Abbott at this link which I highly recommend. Now see how Van Gogh is represented as part of the studies mentioned before:

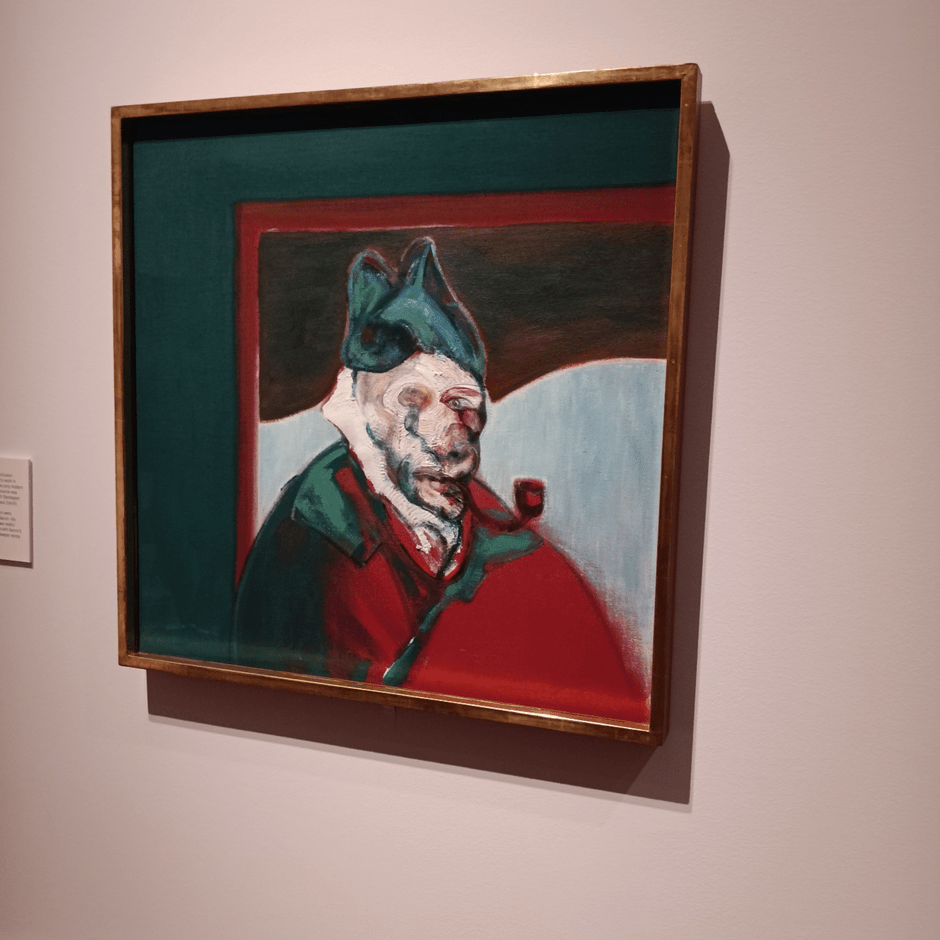

The colours mentioned by Broadley is of course what we notice first but the queering of Figure and ground is much more radical than in Broadley’s ‘monochromes’ and this is an even more important picture, Bacon emphasises the image qua image rather than likeness by distorting facial features and turning props used by the character represented (like the pipe) into obvious graphic simplifications of the thing represented. The image is triple framed and yet stands outside the painted frame inside the actual one (the dark greens of the figure’s clothing fading into the supposed ‘wall’ behind the painted frame that ought to contain the figure but does not do so – the figure spills over the interior frame without ceasing to be an image. Moreover, the face id deliberately different from that of known images of Van Gogh, insisting on the otherness of what is created. And this is the case with Miss Muriel Belcher as well, where the same effects apply (see above).

The point is that colour is in deed brought in as a feature of the portraits after the Van Gogh studies but in these and the Van Gogh studies themselves, this is not the primary learning from Van Gogh. Indeed the colour practice in the portraits (especially of Van Gogh and Belcher is quite unlike that of Van Gogh, using less varied multiplicity of colour markings in the ground and figures than the earlier painter did, and showing much more like, for example Gauguin as an ‘arbitrary colourist’. I hope this picture makes my point:

Laid on top of a reproduction of Van Gogh, The Painter on the Road to Tarascon, the eye is drawn to Van Gogh road and its magnitude and volume, quite unlike the colour spillages in Bacon’s studies, and even the straight colour contrasts are marked out as different from Van Gogh’s observed ones – the green and yellow vegetation is preserved in one but only seen from a different perspective and used to make it difficult to make figure / ground discrimination between the straw hat of the Painter figure and the straw colour in the field in the most greatly deconstructed version of the Painter figure.

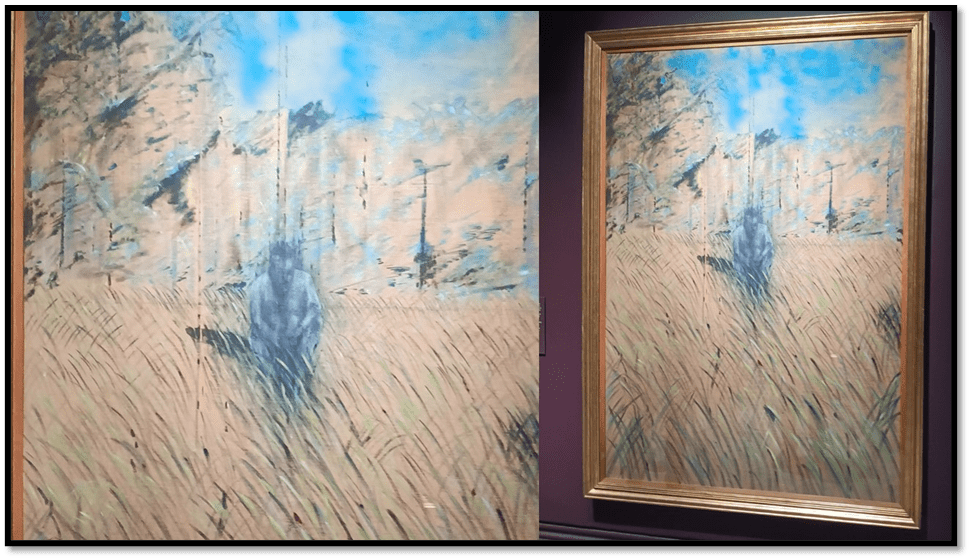

That latter painting is huge (see it here being viewed):

Yes, of course, the painting uses and comments on Van Gogh as a colourist, but it does not use his method, other than in expanding on Van Gogh’s use of a shadow to ‘double’ and problematise the image of the Painter and render it uncanny – as art should do producing in its figurations an image not a likeness. In Van Gogh, the shadow can still pass as that observed when we see a man walking in the heat of the sun, its distortions being that fluid effect captured. Bacon makes the shadow into the thing itself, as much the image as the coloured body id not having taken it over entirely.

The straw hat may fade into the colours of the straw field but the ‘man’ has already become the shadow, deliberately further deconstructed by web-like framing devises around it, such that the image is a dark spider in that web. This, in my view, is what Bacon took from Van Gogh and then took further. It is what he truly meant, in saying: ‘Van Gogh got very close to the real thing about art when he said … “What I do may be a lie … but it conveys reality more accurately”’.[1] And this is not, as a colourist Van Gogh did it. See my reading of the picture below, in my Van Gogh blog (at this link) regarding colour, figure, ground and the primacy of ‘image’ over observed reality in art.

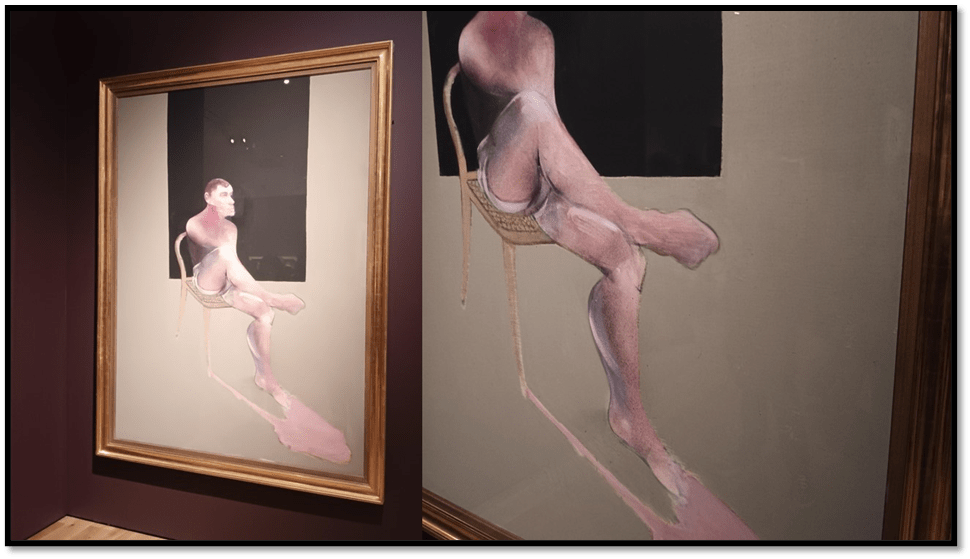

Take another example of the problematical idea in art of figure and ground. Here is Bacon’s 1952 (ought to be monochrome then) Study of a Figure in a Landscape (with a detail):

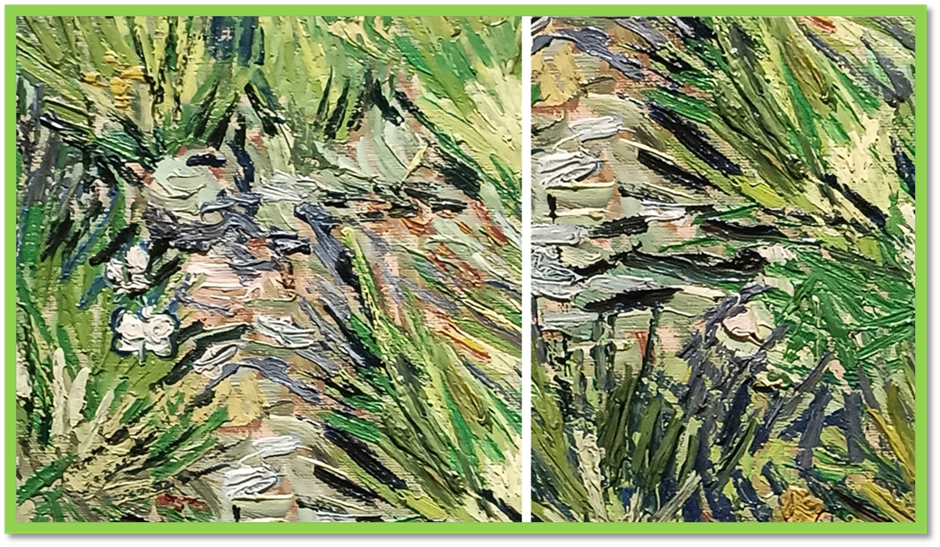

Of course the figure looks imposed on the ground he sits in, perhaps more of the sky his colouring rhymes with than the trees and field of long grasses. The figure-ground relationship is not obscured but rather made too obviously the thing to which to attend, as we close in on the feral in the face, and yet the vulnerability of the nudity (not like that of an unclothed animal). Van Gogh grass heads look similar but his Butterflies are differently related to the ground, rather becoming blossoms rather than differentiating themselves as figures in the detail below:

The method as a colourist could not be more UNLIKE Bacon, though the approach to the ‘lie’ that art might be is extremely close. Hence if you look at both exhibitions do not be guided on the relationship between the painters and portraitists by Broadley. But do consider how the shadow in The Painter On The Road to Tarascon is like a spillage from the figure,. This motif in shadow painting is taken very much further as in the famous painting of the late reluctant lover and heir of Bacon, John Edwards.

The identity of a painted image is truly a slick from the paint used. A shadow is both figure and ground. Bacon makes us see the image viscerally, although here he uses a quire different attitude to framing. I will say more about that in the final Bacon blog. Whether there is an ethical comment on the personality of the sitter is another matter. I am tempted to think this both about Edwards and Lucian Freud (see below):

In the diptych above, colour has meanings. I don’t dare here to name the ones I see. Colour, framing and figure ground are best done in paintings of George Dyer, my favourite of all. I will look at these in my blog on ‘splitting’ images in Bacon, but look at the complex relation of framing, distortion and ‘injury’ (for Dyer’s hand – the one ‘holding’ a cigarette) is severed off) in the painting blow> all of this needs something deeper than Broadley offers. I will but try. Dyer himself said to friends that Bacon’s paintings of him were ‘‘orrible’. I think they need investigating later in terms of horror, bodily viscerality and psychological splitting or ‘shadowing, as explored in the slightly impenetrable 2021 book Francis Bacon: Shadows by Martin Harrison and colleagues.

As ever this is not a matter of taking from Van Gogh a wider palette for the models offering that are legion, but understanding why the earlier artist celebrated that art was a lie – id a necessary one if it were ever to have something to say about the ‘real’ and ‘true’ world. Distortion is part of that – of colour and feature, figure and background and much of that is not done as Van Gogh did it,

Have I met my remit:

Van Gogh, the arbitrary colourist and the real debt of Francis Bacon to him and his shadows.

Bye for now,

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxx

_____________________________________________________

[1] Rosie Broadley (2024: 17 ‘Francis Bacon: Human presence’ in Rosie Broadley (ed.) Francis Bacon: Human Presence London, National Portrait Gallery Publications., 10 – 22.

[2] ibid: 18

One thought on “Bridging Gaps in Personal Learning No. 2 : This blog is based on thinking about the debt of influence of Francis Bacon to his painting hero, Vincent Van Gogh, as a portraitist.”