In the second part of my blog on my birthday visit to London, I predicted what I might write about when I wrote a second blog on it [the first is at this link] based on seeing the work ‘in the flesh’. Saying it was ‘almost certainly the strongest art exhibition I have ever seen’ I predicted rather gnomically that its subject might ‘about the shock of truly great colourist impasto, but it may not, for such work is the path to something much more than innovations in technique in a painter’. On reflection the use of impasto is as good a place as any to start with Van Gogh, for it a technique in which paint apes body, flesh and the mutations of skin and embodied layering of flesh-like coverings and openings. It is the only way to bridge the issue of whether we can talk about the symbolic vision of the imagined body in Van Gogh whilst not confusing him with Gauguin’s rejection of the need for painting ‘sur le motif’ as Cézanne called it or ‘en plein air’ as Van Gogh preferred, without the latter allowing that phrase to mean he was an Impressionist.

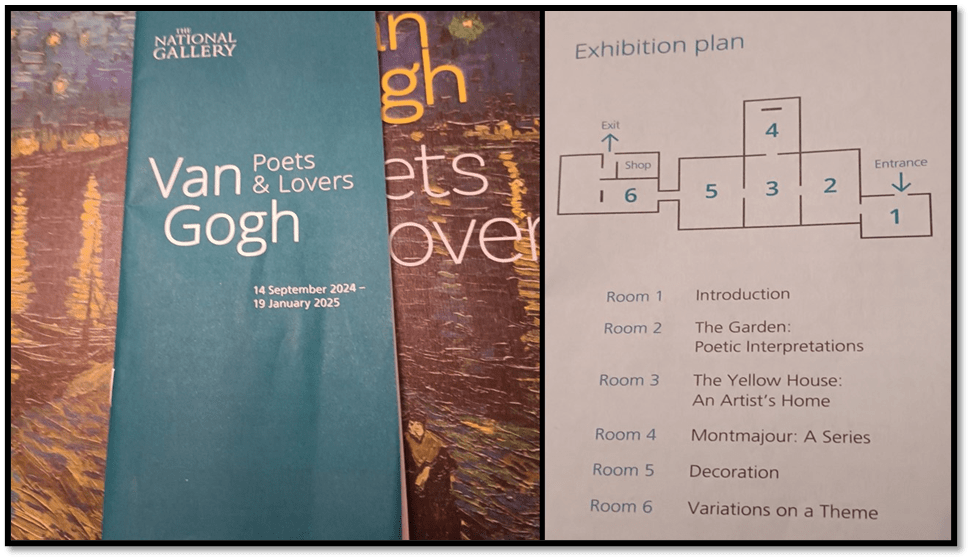

The basics of ‘almost certainly the strongest art exhibition I have ever seen’: the free guide sitting atop the catalogue already introduced in my first blog and the guide to the themed exhibition spaces at the National Gallery in the free guide. The thematic-historical curation of the pictures aims to introduce us to a way of seeing Van Gogh’s work as exemplified in Provence in particular, focusing on symbolic interpretation (focusing on gardens in particular) and utilising a sophisticated interpretation of Van Gogh’s view of décoration as a holistic view of art’s function.

Let’s start with a couple of details from the painting Long Grass with Butterflies (1890) for it is the painting that most caught my eye in the exhibition and I sent out one of these details to friends . It is a detail from a painting that I did not know previously but which amazed and surprised me in regard to Van Gogh’s treatment of natural flora and fauna. As I looked again and again, and refreshed my memory of the curators’ intentions, I found that the constant amazement and surprise throughout was in part because my eyes were open to Van Gogh as they had not been before.

In these details so much suggests the iconic forms of the finite in time and space (and in that sense these icons are symbols but ones that are determinately grounded in the observed ‘real’ forms that inhabit space ’en plein air’ and ‘sur le motif’ (terms in French painting very inadequately translated in English as ‘in fresh air’ or ‘on the spot’). Take the two most basic icons: grass – of which ‘all flesh’ is reducible in the Judaeo-Christian poetry of Ecclesiastes , and the short-lived butterfly, at once fragile in time and the evocation of Psyche (the unstable self of mythology added late to Graeco-Roman mythology). Both this and other signs of efflorescence and its waning are the motifs that Van Gogh hovers over.

These iconic images are stuffed into such densely-packed spaces that the desire to extend beyond, behind, below and within such framing into something we would feign call infinite and never-ending is evoked in the emotion of the painting irrespective of whether the icons therein are recognizable. The painting acknowledges the virtue of human desire alone that is prompting it, for human desire sees itself as a very powerful engine, able to move mountains to render them a form of dynamic energy and stillness – perhaps to both simultaneously.

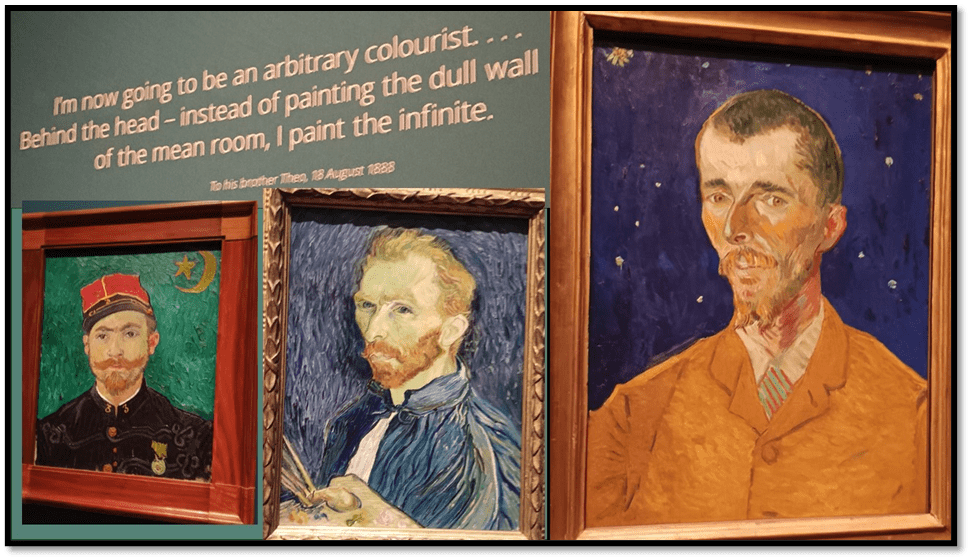

The power of the detail in these samples is locked in the layers of dynamic brushwork and the fusion within them of almost arbitrary colours. Was Van Gogh joking when in 1885 he wrote to his brother Theo that, in relation to the ground against which his portrait figures would stand, he will have become an ‘arbitrary colourist’.

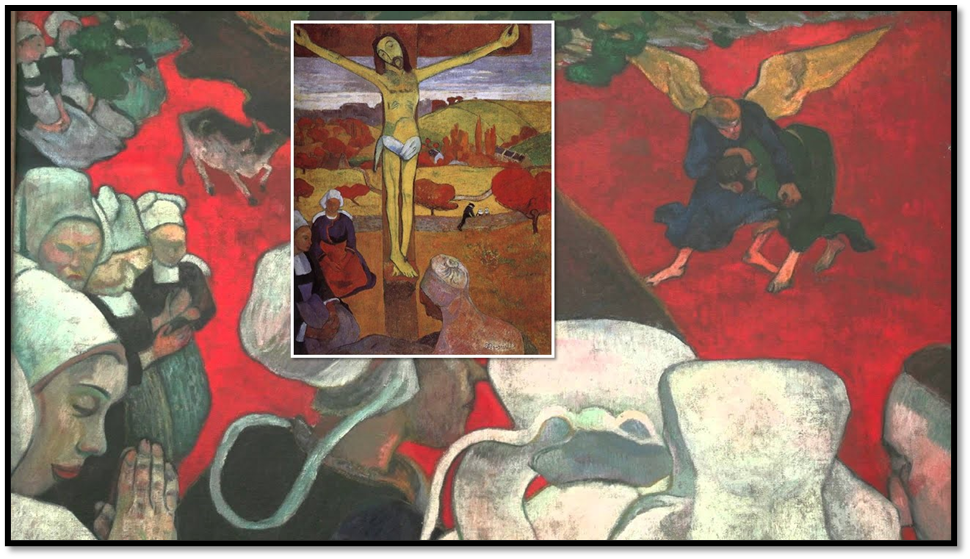

Certainly the ground in which these figures stand is highly imaginative and excitingly coloured but it wasn’t quite like the example of Emile Bernard and Gauguin as ‘arbitrary colourists’, with whom he was in correspondence, that he was evoking. After all ‘dull walls’ are often painted – nay decorated – imaginatively in the real world. The ‘arbitrary colourist’ might be expected in contrast to paint a field in arbitrary solid red patches to form a background to a ‘vision’ that is half dream, as in Gauguin’s The Vision at The Sermon or the figure of a body coloured bright yellow (in the same artist’s The Yellow Christ). In these cases, both Gauguin and Bernard used arbitrary colours to announce the supremacy of the imagined over the viewed landscape in the theory of painted art.

But Van Gogh achieves something that can equally be called arbitrary, for though we might assert i truth to accurate vision of observed realities, it both suggests the temperament framing the vision of observed nature and the thing itself seen with its sociocultural associations tied into it. These are real butterflies, unaware of their short being in space-time but illustrative of it, hovering lightly over grass where efflorescence passes like time itself into the melange of colours that interact and play with the hegemonic tones of green that in the whole pretend to be so much more than they are. The black strokes are particularly ominous and hard to tie down to a merely observed reality. Indeed, I sometimes feel they play a merely rhythmic music function like marks, indicating the frequency of beats in a piece of music. Look again:

That the butterflies could equally be blossoms is important. Likewise, the ground the grass inadequately covers is a multiply coloured richness of physical volumes of colour. Their very physicality bears the signs of the passage of the time taken by brushstrokes of differing pace and pressure. The visibility of that process of action in time is an admission of the artist’s facture without allowing it to dominate conceptually, as in Gauguin. This exhibition, but also a much earlier book makes much indeed of Van Gogh’s debt as a theorist in art, for that I am now convinced he was, to Emile Zola, his favourite author. Zola’s is an influence to which we must return often here if I complete my intended argument (for I read La Faute de l’abbé Mouret written in 1875 – in translation of course, as The Sin of Abbé Mouret translated by Valerie Minogue) over the time I was in London; thatvtranslation being on the recommendation of the curators of this exhibition (although the more shame then that they do not have a copy of it in their shop despite the presence of other Zola works).

In Martella Guzzoni’s book Vincent’s Books, she cites the painter’s comment to Theo on the treatment of light in The Potato-Eaters in 1885. He says l that Theo should not expect literal exactitude in his expression of light because ‘one sees nature through one’s temperament’ . This comment Guzzoni attributes to the influence of Vincent’s reading of Zola’s short essay in lieu of a treatise ’Le Moment Artistique’ in 1883 wherein Zola says that true creative art cannot be ‘réaliste’ and that ‘the word ‘realist’ means nothing to me, and I declare reality subordinate to temperament’.[1]

This is the Van Gogh who appeals to us to think of him differently in this exhibition – not as a loner but an artist deeply interested in communities of other artists and their influence on him – though never in the form of imitation of effects. For me the influence of Zola adds to Van Gogh’s trans-European taste in the written as well as painted art of his time and that extends into influence on his metaphysical politics of human empathy for outsiders that he found in Dickens too.

The organisation of the exhibition follows that of the essays in the catalogue but it economically introduces the exhibition through two pictures only: the first two of figures in which it is clear that Van Gogh looks beyond the person represented to some iconic role. There are several of these portraits throughout the rooms, but the introductory room makes use of two cognate ones that also encapsulate the title of this exhibition : first, the Lover, then the Poet.

The Lover is in fact a portrait of Lieutenant Milliet as a uniformed Zouave (a member of the infantry units linked to duty in North Africa). Successful as it is claimed Milliet was with the ladies of Arles, the painting strains in every way to capture Milliet not really as the seducer of young women he probably was (Van Gogh said that Milliet ‘makes love so easily that he almost has contempt for love’) but as a love magnet to the loving gaze that might in the end capture him and transform his cynical role as a sexual ‘lover’ of women into a true one, the man in whom love is embodied.

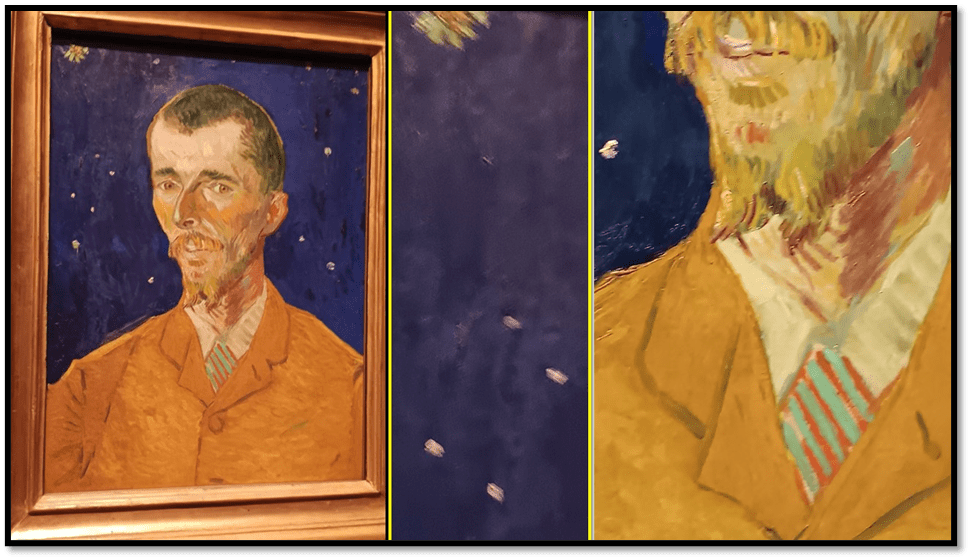

But my topic is impasto painting – the play of layers. And I think it is clear that the background of this painting is less one of a boasted arbitrary colour but of a colour turned dynamic by marks made upon it by something embodied, and witnessed in their absence now in these remaining marks (and perhaps never visible to the sitter). These marks are the marks of variously applied impasto that streak it with emotion. They make us see the raised eyebrow of the man as a sign of something superficial in him to the passions he invokes. The impasto effects are those by which something embodied has caressed the ground behind the figure, finger-marking it whilst fluid into a hardened spatial symbol of passion lost, where even symbols of war are transformed into something less hard and less easy to read. Is this why Van Gogh reverse the Zouave isignia of the star and crescent moon? Milliet resides in the pinks of his ears, nose and mouth (which reveal the strange green tinge in the skin) as thet mark the moment of recognition of another. The lively eyes are part of this too -– each of these features touched with fine impasto brushwork if less irregular than in the green velvet background.

Likewise ‘The Poet’ is a painting less interested in realising the face of the minor poet Eugène Boch, who is its topic than Dante, of whom Boch’s face reminded him. This poet may be surrounded in symbols of the infinite but his skin is also shadowed and marked by lines and patches of arbitrary colour.

Both were associated with Van Gogh’s iconic subject of this period, according to the curators, the garden. It is a garden in which lovers walk, but the roughest impasto of this painting is reserved for the paths which seem to break up any sense of sure footing for those lovers, barely walking in step and oozing distance from each other. The aim of impasto here is to make the dark shadows in the park as solid as scarred flesh.

Whatever this exhibitions sets out to prove about gardens as icons of time in Van Gogh, and whether it succeeds or not may hang I think on the recognition of the means that gardens are constructed and the use of impasto techniques matter throughout. Although I have collected many examples and spent hours making collages, because my husband is ill I have no energy to discuss them all, or perhaps any of them. If I had to hazard a guess at the import of impasto, I would say it is the path to a kind of synaesthetic approach to Van Gogh – the striations of the method conjuring up a mix of senses, especially in flora, as in the examples below:

In both light is approached through complex patterns of colour. To me they operate dynamically, a little like music and evoke a mixture of scents – like those that kill the character Albine in The Sins of Abbé Mouret, a novel oft evoked by Van Gogh to capture the art of Provence in his revision of it. Sometimes the energy of voluminous impasto passages break through the conventions of representation as below:

It is an effect already widely known in A Starry Night on the Rhône.

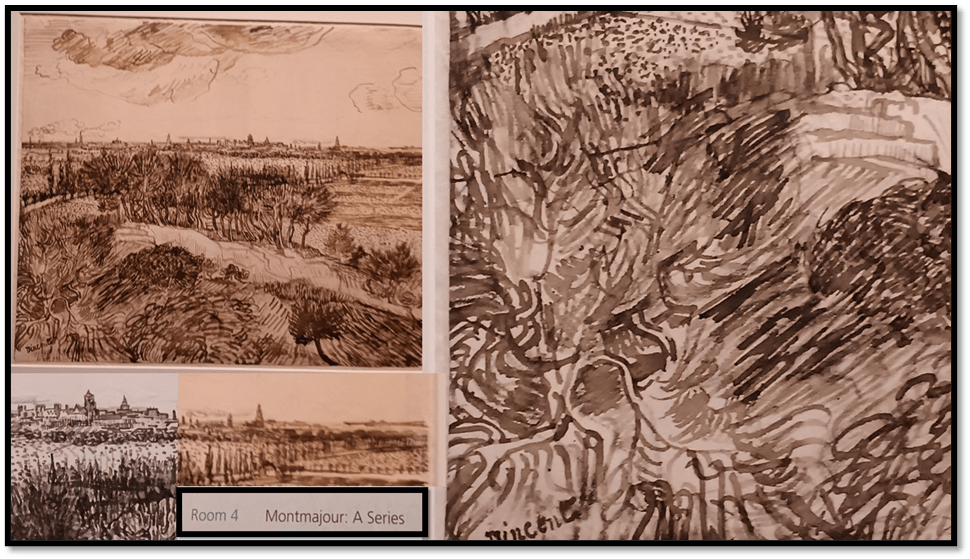

In drawn landscapes the energies are more conveyed in the marks made by a brisk pencil scarring or attempts to show the foreground of what could be a classical landscape in the depth of perspective heavily disordered.

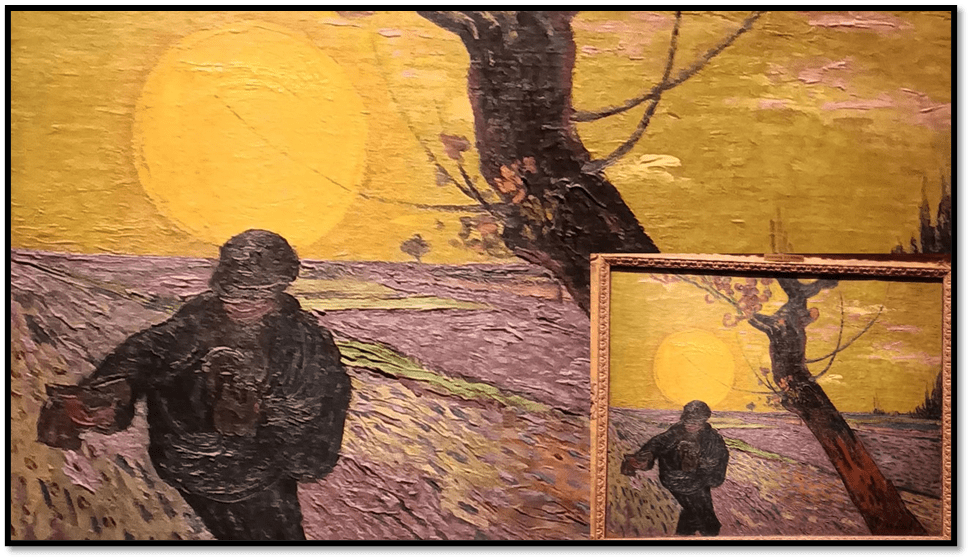

At other times iconic representation entirely takes over as in the representation of the sun in The Sower, which so evokes complex uses of that symbol in Zola’s novel set in this same region.

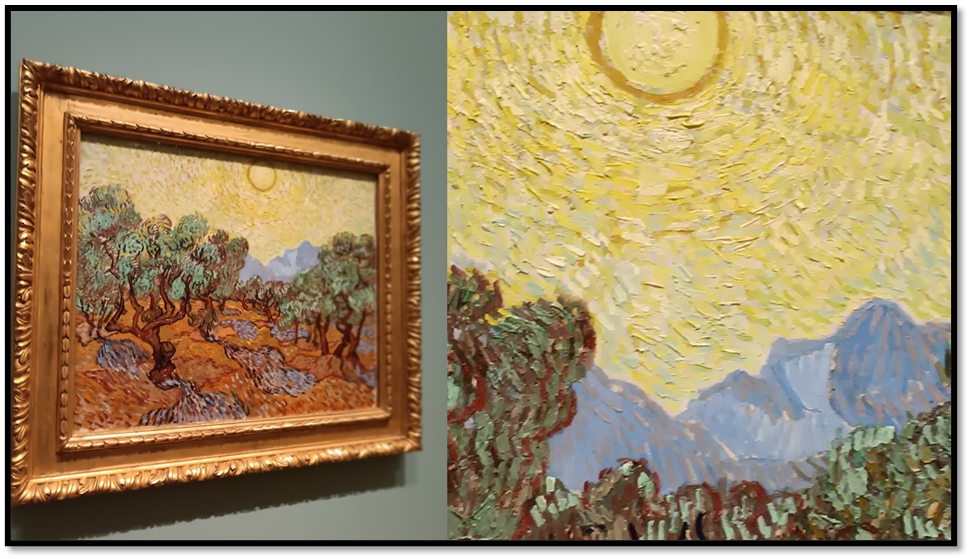

That sun is even more vibrant when set against an olive grove and mountains that it bakes with heat.

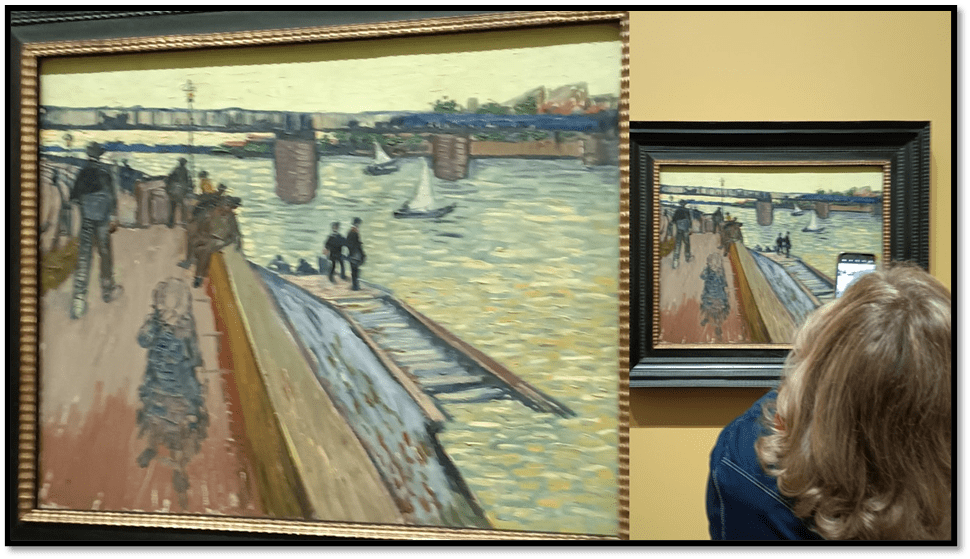

I spent a long time with the Tranquetaille Bridge, but feel no clearer than in my first blog, though here the use of impasto accompanies a kind of minimal approach to the representation of the young girl who is its focus, whose being is no more substantial than the marks coloured as she is periodically on the wall be her. For me this render the painting magical.

If you look at the marks carefully it is as if they register the very sombre tone of a footfall that walks by you neglecting your pain. Placed so near the boat launching slide with its spectral shape that almost make it into the water it runs into and echoes her fate- the picturing of disappearance from the register of human attention.

And then there are the backgrounds of the paired sunflower paintings. I forgot how haunting they are until seen in the flesh.

I had intended this piece to help me to penetrate the mysteries around Van Going in my mind, especially the link to Zola and the potential to what I was going to call naturalist iconography – a view of nature that combined the observed and the hypotheticals of science on the one hand and a link to the symbolic art of the past. It would have centred on the use of ‘Paradou’ (in Zola’s The Sins of Abbé Mouret) as a setting – this for Van Gogh was the place Montmajour, also a garden around an ancient dwelling, set away from the Arles, that he visited with The Lover, Milliet, and about which he wrote to Theo: ‘The two of us explored the old garden and we stole some figs there. If it had been bigger, it would make you think of Zola’s Paradou’. However Van Gogh was far too good a reader not to notice that Zola makes Paradou infinitely extensible to match the narcissism of his lovers in it. Below I link the quotation to an Arles Landscape that is not Montmajour (in the exhibition these are all wonderful sketches and drawings) but it gets the size-longing and passion right.

So let’s end with a drawing of Montmajour (he never drew the garden but rather the rocky rag around the ancient house.

What I have done in lieu of my ambition fails to be penetrating or new and the ambitious project won’t happen. Somehow my mind has collapsed with Geoff’s continuing illness. Let’s see if Bacon goes the same way. I hope not because I am hoping with all my might that Geoff is better soon.

All love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] Martella Guzzoni (2020: 62f.) Vincent’s Books: Van Gogh and the writers Who Inspired Him, London, Thames & Hudson Ltd.

One thought on “‘On reflection the use of impasto is as good a place as any to start with Van Gogh’. Random thoughts about the current National Gallery exhibition.”