At the heart of Rosie Broadley’s beautiful National Portrait Gallery catalogue is a brief essay by James Hall about artist’s studios as self –expression called ‘Corners of Filth & Fantasy’. Hall tells us that Bacon saw his studio as a ‘dump’, and this appears no exaggeration, quoting Bacon as saying: ‘I feel at home here in this chaos because the chaos suggests images to me’.[1] Even if ‘home’ is a place one wants to be it can, you can both hate ‘an homely atmosphere’ and feel that what you know of them is mainly, as Bacon says that of his upbringing was, an ‘atmosphere of threat’.[2] For him ‘intimacy’ is gained when the background of his images is, as opposed to what people may believe to be a ‘homely atmosphere’, instead is ‘very stark’ and the ‘image’ of the person is dislocated and translated from the flesh of the person into viscous paint.[3] That is because, he said, if he liked the subjects he was painting ‘I don’t want to practise before them the injury that I do them in my work. I would rather practise the injury in private’. [4] This blog prepares me for the first exhibition of Bacon devoted solely to the concept of portraiturewith the help of Rosie Broadley (ed.) [2024] Francis Bacon: Human Presence London, National Portrait Gallery Publications.

This blog is part of a series preparing myself for my birthday treatment of art available only in London. Here is the final schedule thereof:

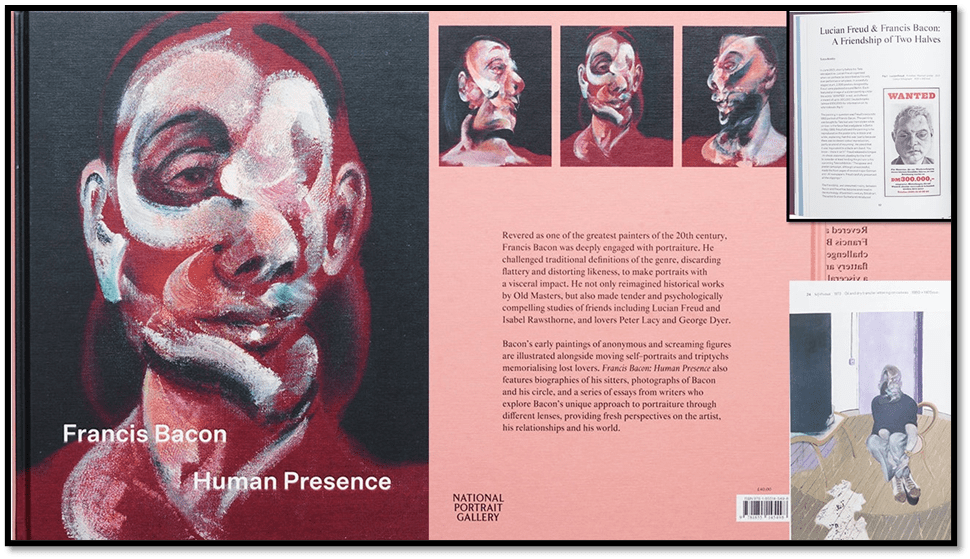

The catalogue for this show may lack the scholarly brilliance and freshness in some of its essays of the Van Gogh one I described in my first blog of this London birthday series (use link to access the blog) but it has better printing finish and clarity of the text of its brief essays, helped by the huge printing font used for the text. Mostly the material is new and informative, and on medical matters truly enlightening, though I thought Gregory Salter’s essay on the meaning of Bacon’s images of ‘queer attachment’ thin and unthoughtful, to say the least, and addressing an imaginary queer audience of the time who actually received Bacon’s images with much more varied reaction and response than the vague pointing to how ‘queer audiences have remade themselves’ in relation to two pictures in particular (the Two Figures (or The Buggers as Lucian Freud knew it) and the images of George Dyer, Bacon’s greatest attachment figure if not his greatest love.[5]

As for the former picture, it was hung in the home of Lucian Freud, who bought it cheap, until Freud’s death, for he refused to allow it to be seen in public, possibly as resistance to the associations to himself it might raise but, as he claimed for its safety (his own famous portrait of Bacon was stolen in Berlin when it was on loan). In the David Dawson photograph below it sits behind Freud, like the promise of a physical violence of attachment that must have strangely on Freud’s self-consciousness as the friend Bacon was lost to some obscure cause and his own indecipherably masked sexual being, even as a ‘heterosexual’ and father of many children to many women.

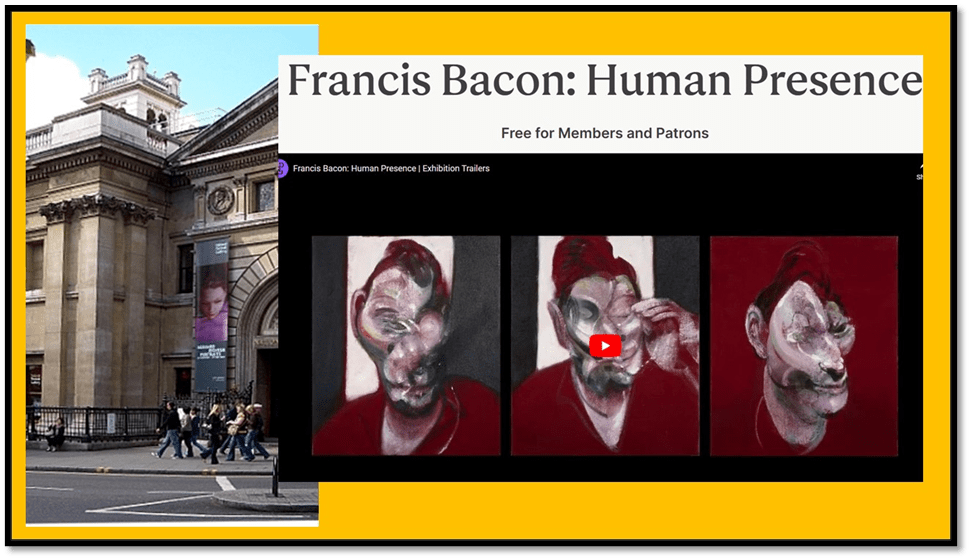

Freud in front of ‘The Buggers’ (his name for it).

As a source of materials – painting reproductions, photographs of Bacon, or ones of others used by Bacon and bearing the crumples and tears of being in his ‘dump’ of a studio) or ones like the above that oft tell their own story, the book is not only beautiful it is essential to any serious collector of books about Bacon, not least the cinephile’s delight that is John Maybury’s essay of filming Bacon’s story, starring Derek Jacobi and Daniel Craig in a luscious bed scene (as Bacon and George Dyer respectively, which also tells the story of how Maybury was mistaken in the Colony Club for Daniel Farson’s rent-boy.[6] I have the video but I would love to see it contextualised in the exhibition. So much then for the beautiful book in itself:

I can’t say that it alone has moulded my expectations for the show, though universally ‘liked’ has raised rather huge differences of interpretation of its value in the current moment. Nancy Durrant in The Evening Standard had been dreading ‘all those screaming heads and contorted bodies in one place – there are more than 50 works on display – but somehow, despite its darker moments, it is oddly uplifting’.[7] Eddy Frankel, the straight-hitting iconoclast of Time Out twice in his reviews states both there ought to be no need for such an exhibition given the over-exposure to Bacon in London recently (he refers to the Royal Academy exhibition Man and Beast I saw two years ago and blogged upon – at this link) and twice rebuffs it by the fact that he is as absorbed in all the old fleshly themes of the painter as ever:

Do we need another show of this major artist’s work? Absolutely not. Could you argue that almost all of Bacon’s work is portraiture, making this show a little pointless? Totally. / But it’s Francis Bacon; you know the deal. It’s full of viscerality, the anguish of existence, the torment of love, etc etc etc, over and over. It’s great.[8]

He had used the ‘etc. etc. etc.’ when he last made the point as representative of so much official art historical ‘blah-blah’ but the first time he said more than ‘it’s great’ in rebuff. He clearly thinks it is, though offering nothing new. I think though there is a need not to keep reproducing the same old thrill for though ars may be’ longa’, I am conscious, or will be the day after my 70th, of my ‘vita’ being more ‘brevis’. Hence I think I relished the fact that a critic I rarely like, and have only grudging respect for, Jonathan Jones of The Guardian said it was, and I have never before heard him say anything like this,

The National Portrait Gallery has assembled a truly biting show of Bacon’s portraits and meditations on portraiture. Not only is it the best Bacon show I have ever seen, it also answers all questions about his greatness. Was he a genius or a showman, a seer or sensationalist?[9]

You would go a long way (I am going a long way) to a show that did this for Jones even though other critics were either a bit playful about the virtue of the project like Frankel or asked less interesting questions of art like looking for where the canvas is ‘full of feeling, soaked in volatile emotion’, like Durrant, or more fulsomely but with no greater understanding of how to name queer emotional content his by Claudia Pritchard of the i newspaper.

It is as if he takes all the pulp and churn of human organs and slaps them on the outside, displaying the essence – the presence – of a being. His portraits, like our internal workings, are terribly vulnerable, but disarmingly complex.[10]

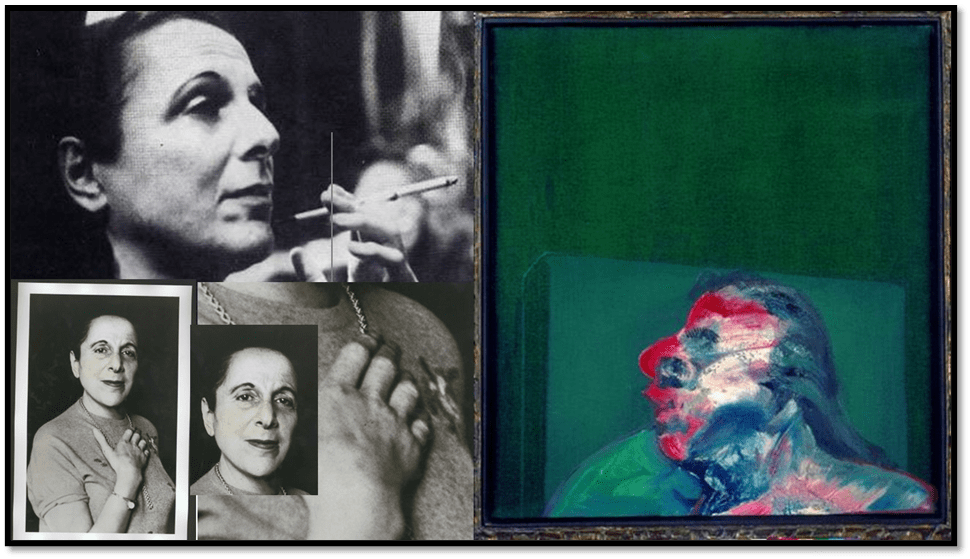

In fact Pritchard’s review is very comprehensive, although I get nowhere with its summation above, for it is so easy to label something complex without detailing the complexity in its contradictions and variety. In my long-form title I pick out various sayings about and by Bacon about the relation of Figure and Ground, a good place to start, because of the conventional interest in it as a mode of discussing portrait, where no assumption is made about the ground being other than a space in the design of the painting that is NOT the figure itself. The excellent catalogue actually makes it clear that this relation changed dramatically for Bacon following his study and then use of motifs from Van Gogh where colour or ‘colourist’ patterning (using rhyming and dissonance between colours) in the painting created more dialogue between figure and ground. As Broadley puts it ‘mostly monochromes of the early 1950s made way for brilliant reds, yellows and greens, which he also incorporated into portraits such as Miss Muriel Belcher (1959). These patterns deepened and complicated the sense of what Bacon meant by an ‘image’ as opposed to’ likeness’ of the person, both of which should be there and both in tension with each other.

In the portrait above, Belcher is receded into a ground that appears both to contain her figurative image and trap her, that entrapments and recession both being a characteristic Bacon is persuading us to see in Belcher. If Broadley is correct that studying Van Gogh changed Bacon’s colour palette entirely I cannot see that as related only to technique. All of the critics except for Frankel miss out the Van Gogh section of the show entirely in commentary, perhaps agreeing with the latter in his summary here:

There are some rare, strange Bacons here. There’s a twisted multicoloured head in sunglasses that’s as psychedelic as it is morbid, a weird, sickly green homage to Van Gogh that looks like a terminally ill Christmas elf, …. two riffs on Van Gogh’s The Painter on the Road to Tarascon that reduce the main figure to an angry mess of shadows. Neither of those last two works is that great.

I had seen the Van Gogh ‘riff’ before in a wonderful show on Van Gogh and Britain at Tate Modern in 2019 (see the very short note on it at this link). Therein I said of that earlier exhibition:

Of course to end the show with Francis Bacon’s very great Van Gogh portrait figures in landscape is a stroke of genius – however obvious it seems in retrospect. Here a very great painter sees into another’s subject, forms, compositional and stylistic innovations. What emerges is incomparable because great on another parallel, whereas strangely my other favourite modern, Bomberg, is great in the exact same line, despite lack of evidence for acknowledged influence in this latter case.[11]

The point is missed by Frankel, ignored by the others. Just as Van Gogh begins to analyse the relation of object and subject forms in a figure, by the traditional use of a shadow self at first and then allowing a comparison of self with external motifs like road, field, tree and their colouration, so Bacon invites the shadow to live in and outside his figure, multiply the different forms in which he is seen, just as the yellow of field and hat merge one into another as if Van Gogh’s self was melting out into the ground of the painting (an even more obvious symbol later) and separating off into alienated forms – like the patch of shadow om the left. By the time of the second riff the Van Gogh figure has become entirely fractally, and less regularly fragmented and dispersed into road, field margin and trees, and perhaps a flow of blood red on the road.

However, Claudia Pritchard’s words are useful as a way of considering in other ways the handling of ground (literally background in her treatment) to figures, which Bacon usually calls ‘images’. Pritchard says:

Bacon turned his back on interior design: his subjects float inside voids, cages and booths. He would only paint people he knew well, and would not contemplate making the portraits of strangers. “It wouldn’t interest me to try to … unless I had seen a lot of them, watched their contours, watched the way they behaved,” he told art critic David Sylvester. A fascinating extract from a television interview with Sylvester punctuates the exhibition. Bacon preferred to paint from photographs, finding burdensome the effort of keeping his models diverted over many hours and sheepish about the “injury” they might endure in his interpretation of their look.

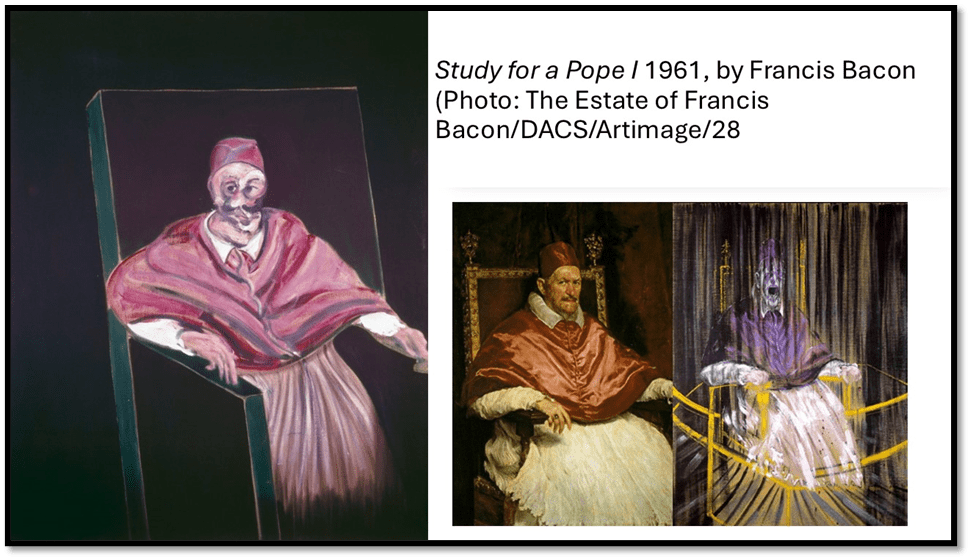

The choice of ‘interior design’ to set against the voids and so on is unfortunate here because I would say Bacon’s intention precisely in the design of cusps between interior and exterior across a number of comparisons. In his paintings, especially the Screaming Popes, figures sit inside a box frame often that is also inside another kind of structure (recognisable or not) as well as inside the true frame of the painted image as a whole. Clearly that may start with the perception of framing devices used by a Baroque Master like Diego Velázquez such as a chair frame on which limbs may be draped. That is all the 1961 Pope I uses (it is a picture that Frankel thinks very strange) but that is only the beginning – for clothing, facial features and shadow all begin to play framing games with this Pope, disturbing his margins, even those of his face, where crevices and orifices open up that Bacon will in later work use much more skillfully, as in the example next to Velázquez’s Innocent X portrait in the centre of my collage. In the much later, and more famed Pope, Bacon uses the ‘shuttering effect to create a slatted external surface over his figure and falling into the image’s deep ground.

The entire issue in the painting is the analysis of what lies inside and what outside, and not just in the obvious way in which bloody viscera usually internal to the body are seen outside the skin. In the 1959 Belcher portrait the reds on the cusp of the figure are truly ambivalent. And this is, as Bacon insists actually what we should, at least in the twentieth century, be seeing in other Great Masters. Jonathan Jones is excited that this show makes genuine connection to older paintings and demonstrates them by having the master and Bacon’s riff there on site (as he show does with Van Gogh too). Jones says brilliantly:

(Bacon) counterpoints modern horror with a grand, heroic sense of the human condition he gets from baroque art. This expresses itself in his big, generous canvases, framed in gold, that situate the vulnerable figure in theatrical, ceremonial space. This exhibition deals brilliantly with his feel for the history of painting. There’s not only the illustration of Innocent X by Velàzquez that inspired his Popes but an original Rembrandt self-portrait he loved.

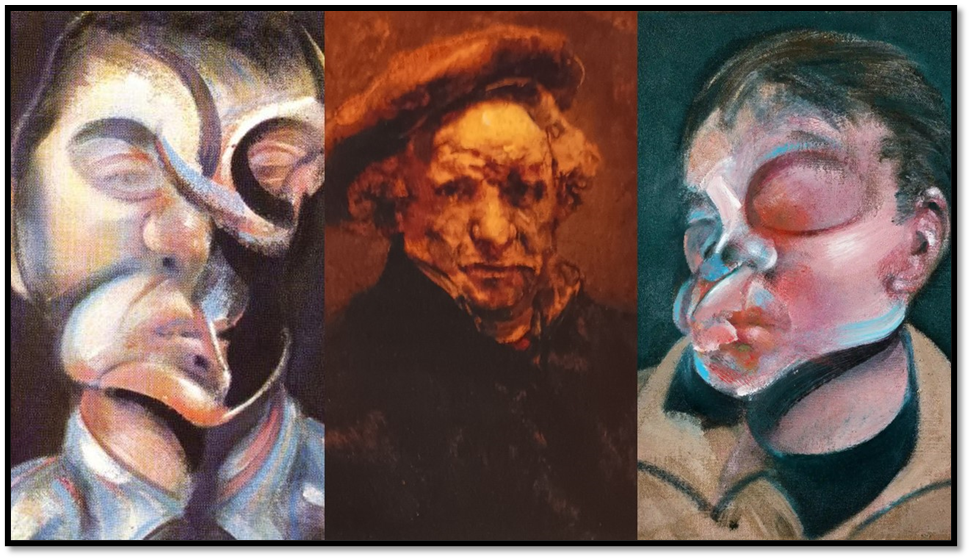

Let’s see it next to two Bacon self-portraits. The distortion in Bacon is different – of course it is.

That is not just because distortion of conventional form was a means of expressing inner form, though it is in Expressionist painters and other, but because the truths one might want to create marks in paint to signify are not unlike the marks real life makes on skin and features. The point about the Rembrandt self-portrait is that close examination reveals fragments of brush strokes put together to form the feel of an expressed whole image, with the contrasts of light and shade, surface and depth and volume and flat passages f reflected light all in interplay with each other and their signification as the detail of a ‘likeness’ or the suggestion of a symbolic painting of an interior thought or feeling by the sitter or about him.

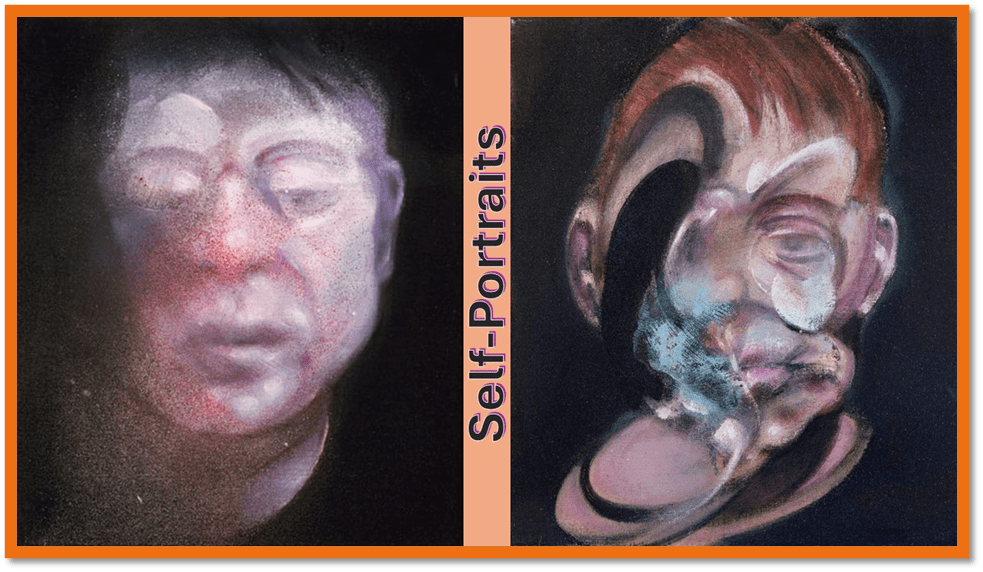

On the right Bacon’s eye bears the bruises he often accrued from the rough play he encouraged in his lovers, once having his eye detached by one (Peter Lacy) but also the interplay of beauty and terror, softness and hardness, understanding and its opposite that faces indeed evoke. None of this yields a simple or straightforward reading of the symbols as a meaningful story, or at least one meaningful story. There are many simultaneous stories – some involving physical interaction, the others not, like the ambiguities of Two Figures between wrestling, sado-masochistic sex and gentle foreplay. See the Self-Portraits below that use what seem extremely different figure-ground relationships and distortions and internal / external mixes of imagery elements – such as holes and absences, shade or darkness, distortion and correction, erasure and restoration.

Left: Self-Portrait, 1987. Photograph: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. Private Collection, NYC/© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2024 / Right: ‘Self-Portrait’, 1973, 1973 by Francis Bacon (Photo: The Estate of Francis Bacon/DACS/Artimage 2024/ Prudence Cuming Associates/Private collection)

And as we talk about interiors we can return to that beautiful essay by James Hall on the role of studio interiors, which contain things buried under filth, mess and clutter, as Bacon’s studio (12 Reece Mews is now reproduced in Ireland) . What is mess and what is truth is partly a question asked by portraits including self-portraits. Again Jones is brilliant here in his discussion of portraiture as likeness or, in Bacon’s term ‘image’. Here is the opening of his review:

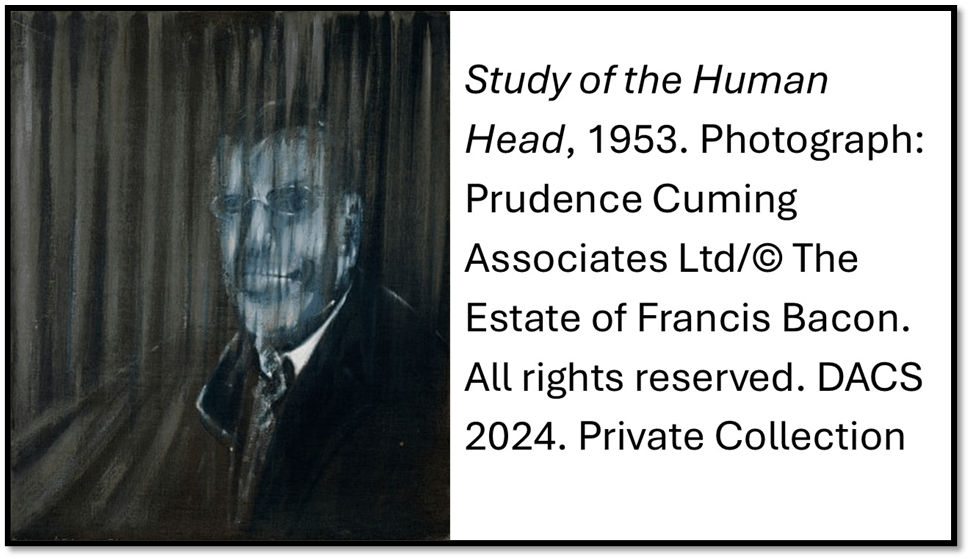

Teeth. We all have them, or start out with them. We’re supposed to take care of them, so we can flash a smile. But for Francis Bacon, they are a glimpse of death in a living human face, a white hardness that will persist when all our soft matter is gone. In Study of the Human Head, a man in a dark jacket smiles out with perfect teeth. Then you realise Bacon has superimposed an x-ray image of the human head on to this living man. It is the grin of a skull.

… The critic John Berger accused him of “horror with connivance”. Fans of fellow artist Lucian Freud still sniff that his friend Bacon was a slapdash, melodramatic artist. And they’d be right – but only if the definition of a great portrait was a recognisable depiction.

This exhibition is a whirligig of horrors without a shred of connivance. …. / The cruelty, you realise, is not Bacon’s. When this British-Irish artist, who was born in 1909, painted his hollow men screaming in transparent boxes after the second world war, there were so many new dead in the world that millions went graveless. The reason trainload after trainload of Jews could be taken to Auschwitz, as the historian Timothy Snyder shows in his book Bloodlands, was that the pace of human destruction in the death factory was unimaginable.

The point about tension between the expectation of handsomeness and the sight of death beneath the skin is brilliant. It recalls Bacon’s favourite Anglo-American poet, T.S. Eliot and his Whispers of Immortality:

Webster was much possessed by death And saw the skull beneath the skin; And breastless creatures under ground Leaned backward with a lipless grin. Daffodil bulbs instead of balls Stared from the sockets of the eyes! He knew that thought clings round dead limbs Tightening its lusts and luxuries.[12]

Bacon too saw war, sex and death in this interplay with modern civility and the Appearance of surface beauty. Of course Lacy was a sadist and he a masochist but that cannot explain the wonderful paintings such as Study of the Human Head (1953), one of those early monochromes with shuttering and teeth that are either on display or being forced out from under the smooth skin by the grin of a dry skull without meaning attached.

But this is all the more intriguing when war is not at issue but merely (‘merely’ he says) the play between love, dependence and death. All of the critics pick out the portraits of Bacon’s male lovers (apart from a sort of playful imitation of Giacometti attached him to the latter’s past mistress, the artist Isabel Rawsthorne. Maybe my view of all this will change (I hope it does) when I see the show but for now it is George Dyer that I want to see and know more about – feel him, as it were, from within. Frankel says:

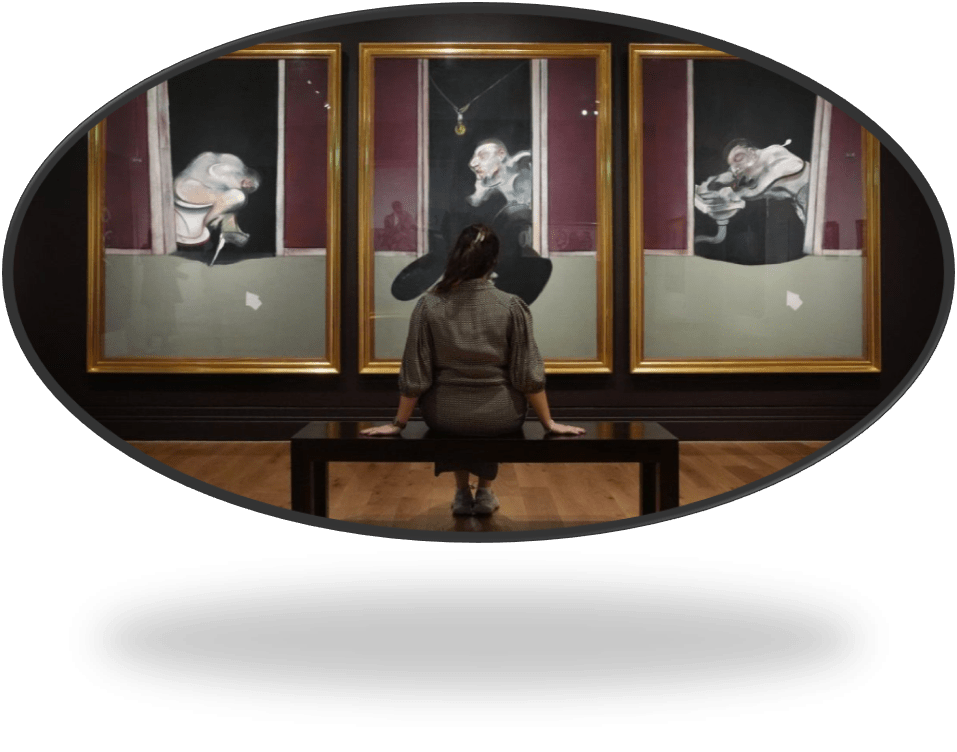

But it’s the portraits of his lovers that hold the most tension and power. Peter Lacy is a large, imposing but fractured presence, while his last partner John Edwards is all smooth, young and pink. And then there’s George Dyer, the gangster boyfriend with whom he had a famously violent relationship. Dyer melts into a puddle of blood on a staircase, he wobbles dangerously on a barely balanced bike, and in the final triptych (depicting his final moments after overdosing in a hotel bathroom in Paris) he curls sickeningly around a toilet, nude and broken and sickly. It’s brutal, painful, too bare, too full of pain.

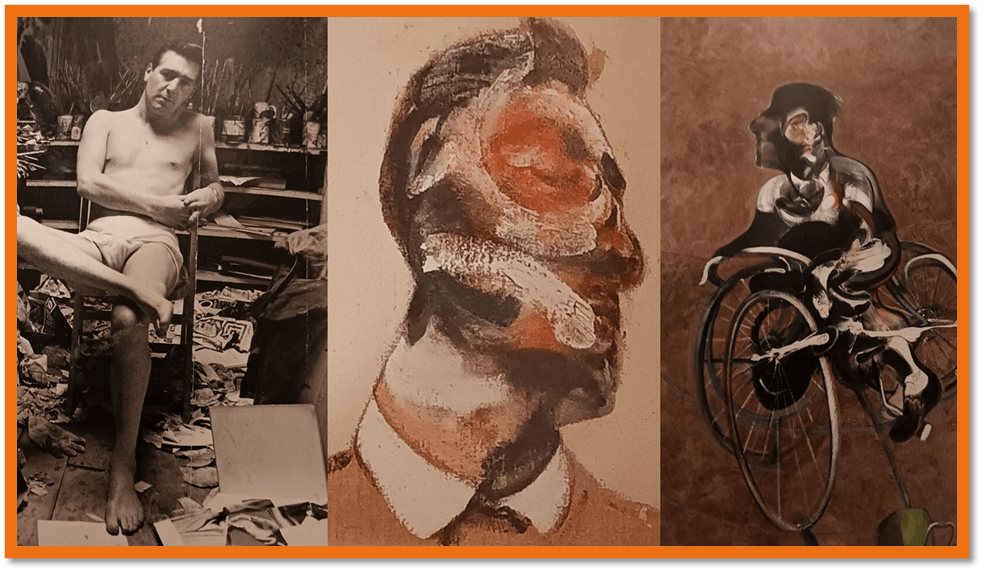

That’s rather good description and I want to see what I shall see in comparison, but that will do for preview purposes. Here are some of the images. However I have also added one of the photograph images by George Deakin of Dyer sitting in the mess of the 12 Reece Mews studio.

I do this because art historians often desexualise queer imagery. In the picture of George Bacon’s want and need of his admirable body, by the standards of the period this was admirable, and the pose that emphasised the crotch of his lover. The apocryphal story is that George was burgling Reece Mews when bacon negotiated that if George went to bed with him, he would not call the police. In fact it appears George first saw Francis at Muriel Belcher’s Colony Room (see my blog on this drinking club at this link). But George is not a mere sex symbol in the example paintings I show here. The picture of George on a bicycle so confounds figure, machine and ground that we struggle to capture an image of George, as if the intense and overlarge central facial detail in skin tones were an image locked inside either the image or its perceiver as a memory of a man going by who is otherwise overlarge for his bike and in peril of the loss of control of it.

One of the wheels (the image is full of shadowed repeats is already buckled as if after an accident, actual or merely foreseen. The age of the figure shifts from a kind of cartoon of a boy with overlarge and generalised features to a more closely observed eye catching yours. The semi-circles on the ground seem to force George into a motive track not of his choosing but he goes anyway. We feel the front wheel turning as we see the head and face turn. I need to see this painting.

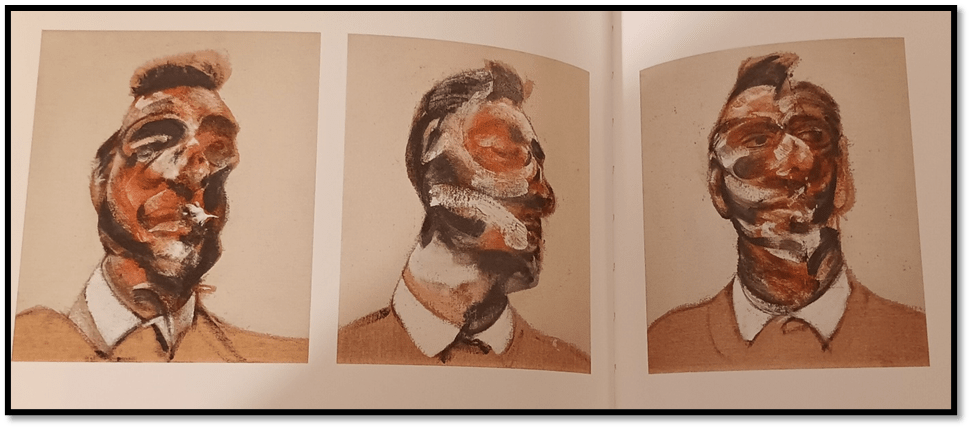

The study of a head (the central image in my collage) is one of three and is, I think the most complex. It bears the marks of ither bruises or the sign of the passion of the viewer circling on his eyes, nose and mouth – which we see both in profile and fully frontal. I find it extremely beautiful where distortion serves that purpose born in the gaze of the viewer rather than some sly intention perhaps suggested by others in the triptych. George appears in these as a man of humour, passion, some readiness to deceit but also as a man Bacon found beautiful and with whom, sometimes despite himself, he was in love.

There is much more me to ponder on my visit. Not least its final images – the triptych picturing the death of George Dyer that Francis did not see but which haunted him Still my beating heart. I really mean that. I have only seen these images in reproduction before.

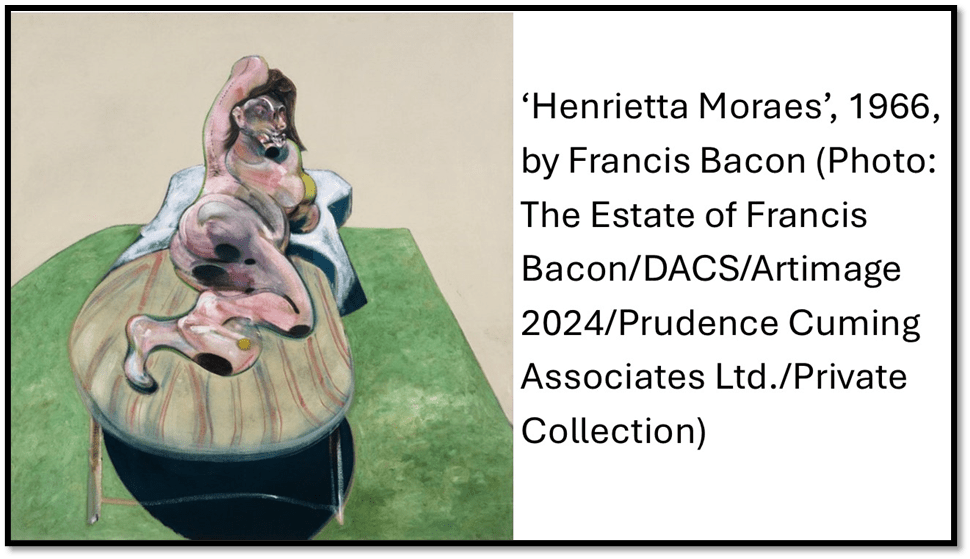

I can only apologise that the impression leave of the important friends and subjects of his painting is so sketchy. It will remain for now at the level of picking out a picture of each Henrietta Moraes and Isabel Rawsthorne. Moraes picture is anyway the nearest we get to the nude, especially the reclining nude of tradition (Henry Moore’s subject) is sculpted to show the softness and vulnerability of flesh. Henrietta’s body is bruised apparently, her body full of cavities into darkness or from which darkness is exuding. I need to think more about this.

The Rawsthorne picture I choose shows three modes of Rawsthorne – as a stilled but bizarre Gothic mask, a woman seeking entry from the dark surreptitiously and a figure who uses a key to open up things (doors of course (but to or from what) without regard to what is loosed. I have never seen either picture in the flesh.

One picture I want to see too is the Head of Boy from 1960 for to me this is probably the one that I saw in the book that most intrigues me to ponder. Its use of green in figure and ground reminds of Belcher the year before , but this is a picture of extraordinary attraction I think, unlike any other Bacon I have seen in its tendency to pull the viewer into the spaces and feel of the face, as if to touch an ear or chin was to be absorbed into the green fabric the boy wears. The moth is deeply sexual but threatening as you ponder perhaps. It is a face that one suspects as one eye pondering, the other pulled into its orbit of attractive offering of itself.

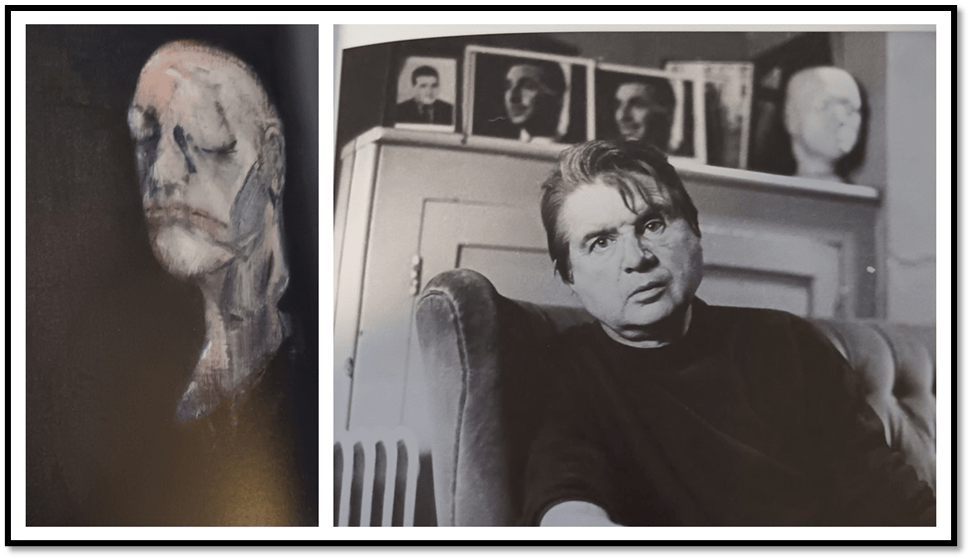

Until I see it for real I can say no more. But I want to finish, with the material the catalogue stars with. A photograph of Bacon with a cheap plaster replica bust of the death mask of William Blake behind him on a shelf and a detail of the painting he made of it in 1955.

Again I want to see it (for the first time) but it seems to me both far from simple and far from monochrome. It plays with the idea of boundaries between outside and inside, flesh again against sculpted form, as much as other pieces but to what purpose I yet have no guess about, though the catalogue is full of suggestions about a tradition of ‘close-up heads’ in still photography and moving film that I need to consider in situ, especially the work of Helmar Lerski about whom I have more to learn but well-illustrated in a scholarly brief essay by Richard Calvocoressi. One piece of this essay is especially suggestive as the author writes of Lerski using ‘multiple views of the same face evoking an existential idea of human identity was fluctuating and contingent’.[13] And there I have to challenge Frankel again who says quite without cause in his review: The self-portraits are maybe the least successful things here, other than that Van Gogh painting.‘ What Frankel misses is a point oft made in the catalogue – that Bacon often merges likenesses of self and other (or others) in his portraits that the concept of ‘self-portrait’ might itself be a little dubious. It would appear that this event will be exciting, challenging and so fulfilling. Let it come.

So that’s my final event pre-blogged. Now to wait for Friday, starting would you believe with my anti-shingles jab at the local GP surgery for which I become eligible on Thursday.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] James Hall (2024: 73f.) ‘Corners of Filth & Fantasy: Francis Bacon’s Studios as Self –Expression’ in Rosie Broadley (ed.) Francis Bacon: Human Presence London, National Portrait Gallery Publications, 68 – 74.

[2] Rosie Broadley (2024: 13) ‘Francis Bacon: Human presence’ in Rosie Broadley ( ed.) op.cit., 10 – 22.

[3] Rosie Broadley ( ed.) op.cit.: 39 (editorial material)

[4] Rosie Broadley (2024: 17) ‘Francis Bacon: Human presence’ in Rosie Broadley ( ed.) op.cit., 10 – 22.

[5] Gregory Salter (2024: 51) ‘Queer Attachments to Francis Bacon’ in Rosie Broadley ( ed.) op.cit: 48 – 51.

[6] John Maybury (2024) ‘Ghosts in the Glass: Filming Francis Bacon’ in Rosie Broadley (ed.) op.cit: 174 – 180.

[7] Nancy Durrant (2024) ‘Francis Bacon at the NPG review: a gut punch of a show that’s oddly uplifting despite all the darkness’ In The Evening Standard (9 October 2024)available at: https://www.standard.co.uk/culture/exhibitions/francis-bacon-at-the-national-portrait-gallery-review-b1186664.html

[8] Eddy Frankel (2024) ‘Francis Bacon: ‘Human Presence’: Anguished, tormented portrait by the guy who basically invented anguished torment’ in Time Out (Wednesday 9 October 2024) Available at: https://www.timeout.com/london/art/francis-bacon-human-presence

[9] Jonathan Jones (2024) ‘Francis Bacon: Human Presence review – ‘This whirligig of horrors is the best Bacon show I’ve ever seen’ in The Guardian (Wed 9 Oct 2024 00.01 BST) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2024/oct/09/francis-bacon-human-presence-review-national-portrait-gallery-london

[10] Claudia Pritchard (2024) ‘Francis Bacon, Human Presence review: Explicit and exhilarating’ in the i newspaper (October 9, 2024 12:01 am(Updated 2:50 pm) Available at: https://inews.co.uk/culture/arts/francis-bacon-human-presence-review-3312374

[11] THE EY ‘Van Gogh & Britain’ Exhibition: Tate Britain Seen 02/05/2019 – Steve_Bamlett_blog at: https://livesteven.com/2019/05/06/the-ey-van-gogh-britain-exhibition-tate-britain-seen-02-05-2019/?_gl=1*1p56o29*_gcl_au*OTg1MjkwNDQxLjE3MjYwNDY4NDI.

[12] T.S. Eliot Whispers of Immortality | The Poetry Foundation available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/52563/whispers-of-immortality

[13] Richard Calvocoressi (2024: 36 – 38) ‘ Francis Bacon’s Close-Up Heads: An Overlooked Source’ in Broadley (ed.) op.cit: 32 – 38.

2 thoughts on “This blog prepares me for the first exhibition of Bacon devoted solely to the concept of portraiture with the help of Rosie Broadley (ed.) [2024] ‘Francis Bacon: Human Presence’.”