“If you can get the balls in, you will”. Elisabeth Frink quoted her mother as saying to her of sculptural work to her official biographer, Stephen Gardiner. She used this to illustrate her love of symbolic and embodied passion, imagined as entirely male, that is quite ‘the opposite of passive … somebody who can be extraordinarily emotional, but one senses they are composed. They’ve got it in there and can unleash it if they like. … ‘.[1]How would we understand the sexual and gendered ethics of sculpture, if that is possible? This blog prepares to revisit Yorkshire Sculpture Park to resee their Frink collection after reading Stephen Gardiner (1998) Frink: The Official Biography of Elisabeth Frink, London, HarperCollins Publishers.

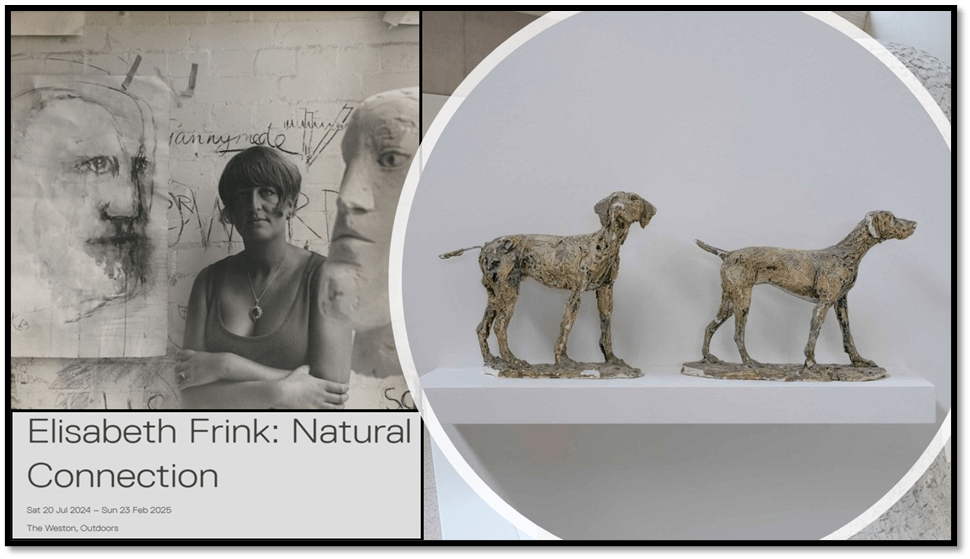

In an earlier blog based on seeing the small exhibition commemorating the receipt of new materials to add to their collection of Elisabeth Frink sculpture and graphic or plastic art studies, I said:

I have to do this blog to commemorate the enjoyment I felt in art about which I feel and am largely ignorant. Since seeing some of my errors I have ordered some reading on Elisabeth Frink to try and improve on current ignorance, but that is for the future rather than this blog.

This new blog serves a dual purpose:

- To revisit the sculptural art of Frink and to prepare to resee works I understood, beginning with those at The Yorkshire Sculpture Park, poorly when I saw them the first time. My hope is that reading Frink’s biography will have promoted more comprehension of how Frink saw culture as well as how she realised those perceptions.

- To build on perceptions of Frink’s mythicised grasp of sexual pleasure, identity and politics, especially around the ethics of male violence and the ungendered contrast between ruthlessness and pity in sculpture and life.

Approaching a rethink of Elisabeth Frink through biography has its limitations, particularly in the case of Elisabeth Frink, whose life is so contradictory. Born from a relatively wealthy rural army family, she was brought up in a world dominated by masculine country’ sports’, including fox hunting that she seemed to both hate and cherish with equal ardour. Even in her later homes, witnesses speak of the hunt gathering in front of her door, and her attraction therefore to horse and rider combinations cannot be reduced to her interest in symbolism alone. Stephen Gardiner is puzzled too that a woman who claimed such pity for the vulnerable, and acted upon it in charitable work, could also be so ruthless in the protection of her own interests as in her support for legal action of her friends, a couple known as the Crackanthorpes, because she thought better of selling off the flat they rented from her in France at a knock-down price originally suggested by her.

In that action, though, she never relented in pursuing her interests; continually expressing feelings of sorrow at the vulnerability the couple thus exposed to being homeless, especially when their daughter died amid the process of eviction.

There feels to be a tendency in her to hide behind the rather feral men who guided her, in the pursuit and eviction of her once dear friends from a flat they thought already sold to them by agreement. But she could be ruthless with these men too – inclined to fall in love easily and out of it, onto the next venture just as easily. In telling these stories, Gardiner seems to have no clear explanation of her shifts of love interests bedsides her undying professed interest in men and of sex with men, that even registered in the size of the phalli she gave her male figures reflecting her most recent man, on which she modelled her latest male figures, whilst professing the irrelevance of those features to her personally (sometimes – she laughingly told Gardiner – she liked men ‘big’).

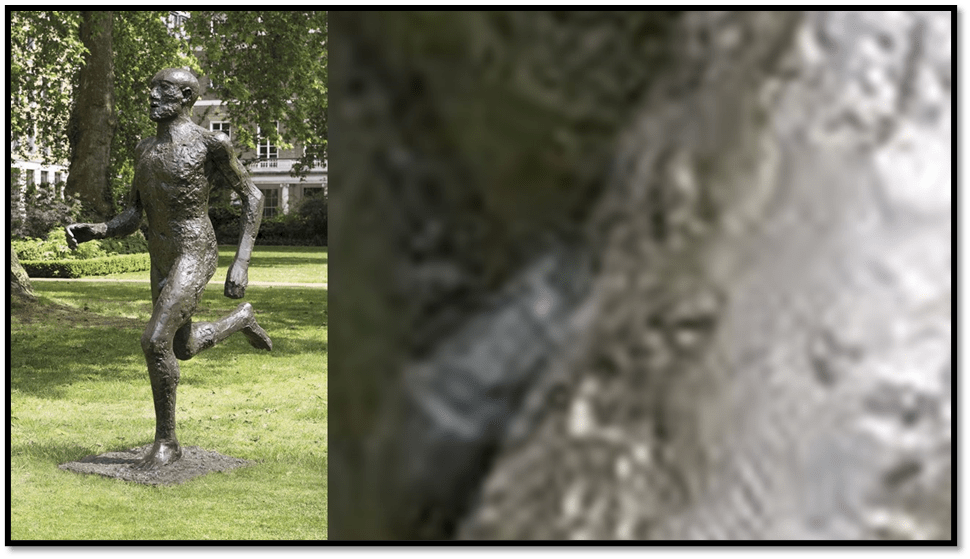

A strange debate emerged around the figure The Running Man (versions appeared from 1980) commissioned for and erected in Salisbury and representing an asylum seeker. This figure, Frink insisted, in rather angry response to the fascination with cock size in the newspapers, was “a tribute to human rights. It is a man running away from persecution”. To The Daily Mirror reporting of women both shocked and fascinated by that detail (‘I wish he was real. After all, who could say no to such a well-appointed man?’, they quoted one woman as saying) Frink said that ‘these women had got the wrong end of the stick’ and reminded them that with a husband and 22 year old son she need to omagine no fantasy men. [2]

The debate has the problem within it locked as if in a nut shell. Frink could say that : ‘My art is always about humans, and more and more I think about those who suffer’, though exploring this from animal-human hybrids.[3] At the same time she admires the sheer energy of the persecutor as well as the man underneath the vulnerability of a man turned chased down victim BUT ready to turn against him. Such men seemed to represent an energy she could not entirely condemn.

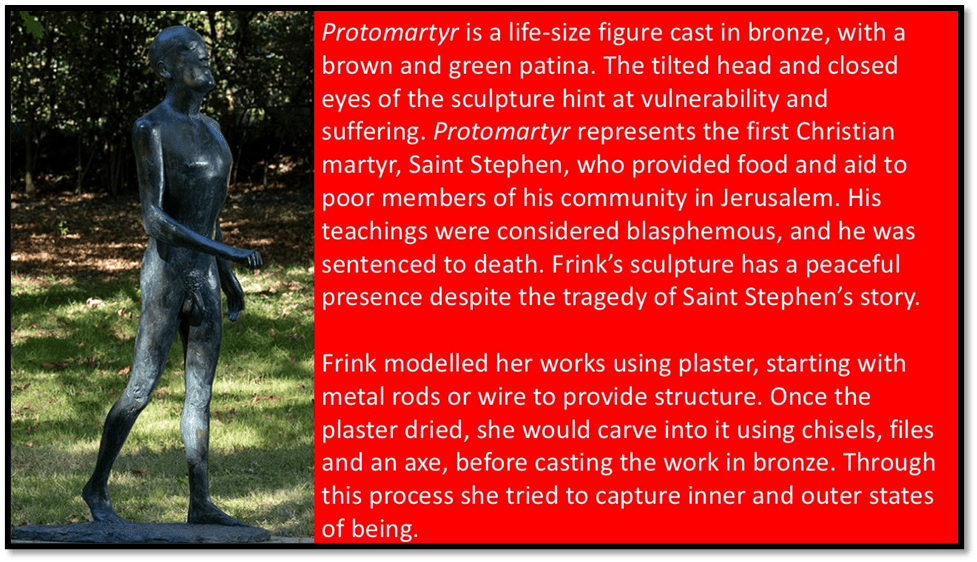

The persecuted man and the persecuted animal exist alongside a tolerance of fox-hunting and an acceptance that cruelty like it happens, though ugly, especially in war – second-hand experience she had of which in her father’s career and worries for him. At Yorkshire Sculpture Park (YSP), there is a piece I should see, called Protomartyr (see below) based on the story of Saint Stephen, stoned to death because of accusations of blasphemous preaching.

Protomartyr is naked too and endowed with noticeable genitals but Frink herself saw this male figure as something that failed to represent her idea of humanity because, although she stressed the figure, like Precursor from the same period, was ‘gentle’ and ‘slender’, as if she admired the qualities admired and demanded by her commissioners, Gardiner says ‘she didn’t like them much, thought them “weak”’, attuned to a period in her life – the parting from Ted Pool – where she needed to be “reinforced”. Once she was she decided to express her distaste for these over-feminised men (in her view) by wanting ‘to do more dynamic things, like the “running men”, for stance, which I started doing then’.

If we look again at The Running Man iconography, size of sexual parts aside, Gardiner is right to call these figures ‘strong and sinewy’ and some of them robust and heavy’. Though running away from something, in ‘battle’ as she sometimes suggested of these men, unlike protomartyr (destined to be an eternal victim such as Christianity venerated on earth at least, these are also men who can and will turn from being a victim, though they are victims in the precise moment captured from time.[4] It is as if Frink could only conceive vulnerability in men if that vulnerability was also something they could cause other people to feel once they were ‘reinforced’. I find this deeply disturbing and representative of system of binary thinking about sex / gender that almost eradicates women from the plot whilst pretending that the dominant side of the binary is representative of both.

In the end what we observe in Frink’s sculpture is something that preserves synaesthetically the ideas and feelings about maleness that characterised sex/gender politics of the period, especially that which resisted feminism or modified its application to the understanding of masculinity. There is more than meets the eye to Frink’s mother saying to her of her work, as cited in my title, “If you can get the balls in, you will”. The balls here are a metonymy for the whole male sexual apparatus of course, that shows little or no interest in female genitalia which become a mere absence, as they are largely in Frink’s work. That absence elides with what I see as a terrible ambivalence about the male as an instrument of female pleasure in the early 1970s.

Gardiner says of her illustrations to The Canterbury Tales in 1972 that they show too close an interest in the mechanics and equipment of the sex act and ‘touch off, as sex scenes in films can, the feeling one is a Peeping Tom’ and are so particular in their need to display the minutiae of male sex as an imposition so narrowly ‘they might have been drawing horses mating’.

But his point about this is combined with an anthropomorphic reading of the new form in which she sculpted horses at this period, as a source of energy – human horsepower as it were – that needs to be seen as in flight and fear of its power as well as erect in it. Gardiner moves onto her interest in hoses in a prone position, of which she says of the emotion involved in seeing a prone horse that: ‘It’s just the shape that’s so fantastically sensual. They’re so vulnerable’.[5] The maquettes in the Frink show currently on in YSP of these rolling and reclining horses make the point. The rolling, reclining horse is still a symbol of the phallus but of the phallus in submission and play that is no longer hard and male:

Immediately after treating of horses, Gardiner seems to suggest why these figures related to human sex as overly carnal in The Canterbury Tales illustrations. I give the quotation more fully, in which he plots the contiguity of the horse work and the pictures in the Tales in 1971. The rationale he gives was, summarising Frink, was that what attracted here was ‘to do with contained energy’.

That is what appeals to me more than anything. It appeals to me in people. Somebody who is entirely composed … entirely. Quite the opposite of passive … somebody who can be extraordinarily emotional, but one senses they are composed. They’ve got it in there and can unleash it if they like. I try to translate this into my figures, the last man has probably got what I want.’ (referring to Man of 1970) ‘My mother’s very good about the naked men. “Oh, If you can get the balls in, you will”. [6]

Balls rather than phallus, note, for the interest is not in the present energy but the contained energy ready for action, even whilst a horse, for instance, (or I’d say a phallus) is in relaxed state. So many of Frink’s earlier hybrid animal fantasy have the shape of a semi-relaxed phallus or one about to come into full power. Below I give some of the wonderful maquettes of birdmen in the present exhibition but see these illustrations too from Gardiner’s book:

Illustrations in between Stephen Gardiner, op.cit: 106f. (p, of the unnumbered glossy pages followed by maquettes from YSP).

Her the phallus shape is almost erect but its non-finito state is conveyed by the unsteady legs of the animal to which it is a body. The Birdman is the perfect picture of Frink’s belief that her birds represent the male aspiration to flight and regulated control of the air. Of course, she saw it not as male but human, but her figures are as identified as male nevertheless.

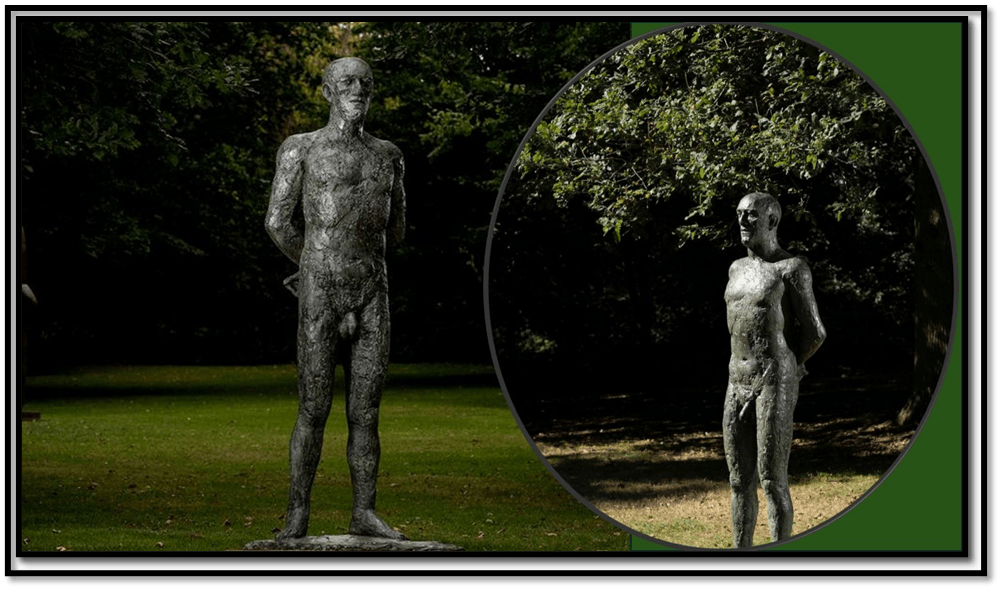

How will any of this help to re-see the Frinks at YSP? It would be best to concentrate on the later works, for (apart from the new maquettes in the exhibition – and not all of them) Bretton Hall (as YSP was then) was a late buyer of her work. The Standing Man is a magnificent but monstrous sized giant man – standing 6’ !0” tall – intended for W.H. Smiths in Swindon.

I have never seen it in the flesh at YSP. The text at the page at the YSP website follows through, however, from some of the themes I have addressed, implicitly linking the interest in contradictions between strength and vulnerability in the masculine to the hybrid animal / human forms of earlier work. But there is something new I think. Male strength is recreated as beautiful, but the more so in its relaxation in expectation of oncoming excitement, yet without shame at the full frontal nudity.

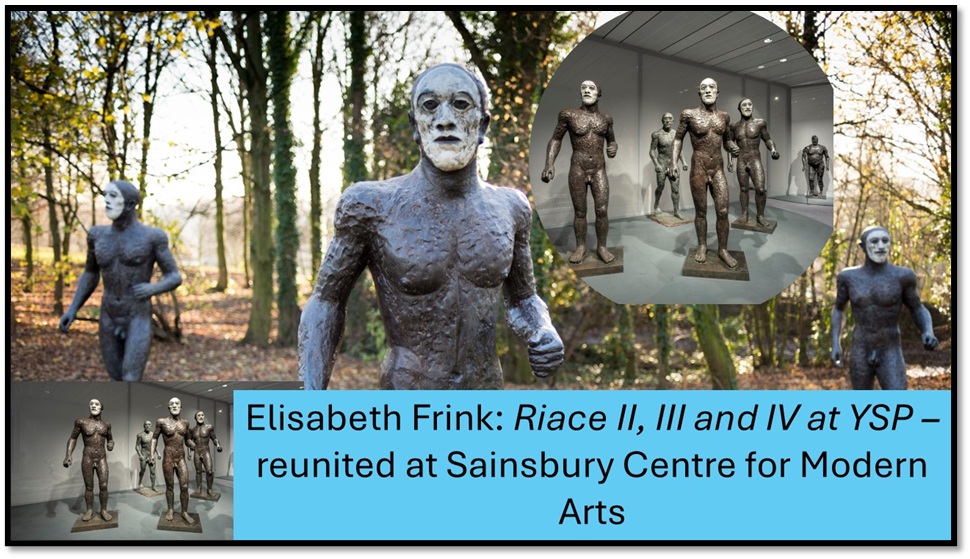

However, following on from the Riace figures (of which more later since YSP has most of them) there is something not only contained, because any containers holds (and holds back) energy stored within it but also contained because secreted. In the late works – many marriages later, usually seen as a reflection of her sexual appetite – men seem to be deceitful, masked. This went with the fact that the discovery of the figures near Riace, Reggio gave the first evidence that Greek sculpture was polychromatic – it was painted – in a way Winckelmann would have been shocked to register. The Riace figure were retrieved with the look of a mask over their faces and this (and the use of reflective goggles in The Goggle Heads) became a sign that masculinity not only contained pleasurable and positive energy but awfully dangerous energy for women. Again though the idea is better expressed in the ‘masked’ Riace Heads.

A nuanced example is The Seated Man, also at YSP, for he mask is not indicated by an obvious mask or paint as such but the clear indication that an expression has been set in the face, with almost a boundary between head and facial expression, that is incommunicative and sinister. The man may pose like Rodin’s The Thinker, but his intention is not only hard to discern, it raises suspicion that the intention is hidden for a good reason.

Even the beauty and agility of the body may be a mask for an ulterior motive. Such ideas must have been common in Frink’s extensive knowledge of men. This man was modelled on Alex, her last husband, an irascible man continually rubbing people up the wrong way and mercenary with money. He was behind Frink’s actions with the Crackanthorpes. The Seated Man was made in the early days of her third marriage (to Alex).

Gardiner makes the tension of this period clear. There were residual issues over Ted Pool, her second husband, whose love she treated, at first, as the beginning of an idyll. But the decision to move from being illicit lovers to marriage with Alex was also fraught. In making her decisions, Gardiner suggests that she adopted an ‘immature brutality’ in carrying them through usually thought of as male behaviour in relationships. Moreover, asked if she was dependent on men’ she said: ‘Oh, yes. Definitely. Emotionally. Physically. Every which way I’m totally dependent on men’.[7] Gardiner does not trace the tragic streak in this and the fact that her only identity posture for herself was a male one, its energy greater than any real man. She often referred this to an interest in myth. She described the statue as ‘Aztec’, though she never went to Mexico.[8]

Likewise, she only knew the Riace figures from photographs she saw in Sicily near the time of the retrieval from the sea, because the works themselves were in Florence on exhibition loan. What attracted her was not any abstruse idea of a new antiquity discovered but the fact that they brought to her concept of masculinity a new emotional perspective, describing them as ‘very sinister, but also very beautiful’.[9]

The example of these figures fed into the iconography that she had developed for the goggled heads in which a kind of calculating coldness was introduced by goggle covers to men’s eyes. Some male critics respond badly to them The very self-seeking critic of The Observer, William Feaver, who was to play many games in his relationship to Lucian Freud, was entirely unsympathetic to a female artist finding negative emotional material in men she still considered beautiful and still needed, even in their tendency to violent abuse.

She called the masked / goggled men a ‘statement on my part about the cruelty and stupidity of repressive regimes and of the men who operated them’. I am sure that she did not need the evidence of repressive régimes abroad to see this problem in male narcissism, even though she herself identified with it. To Feaver though they were merely “stupid, boring Goggle Heads”.[10]

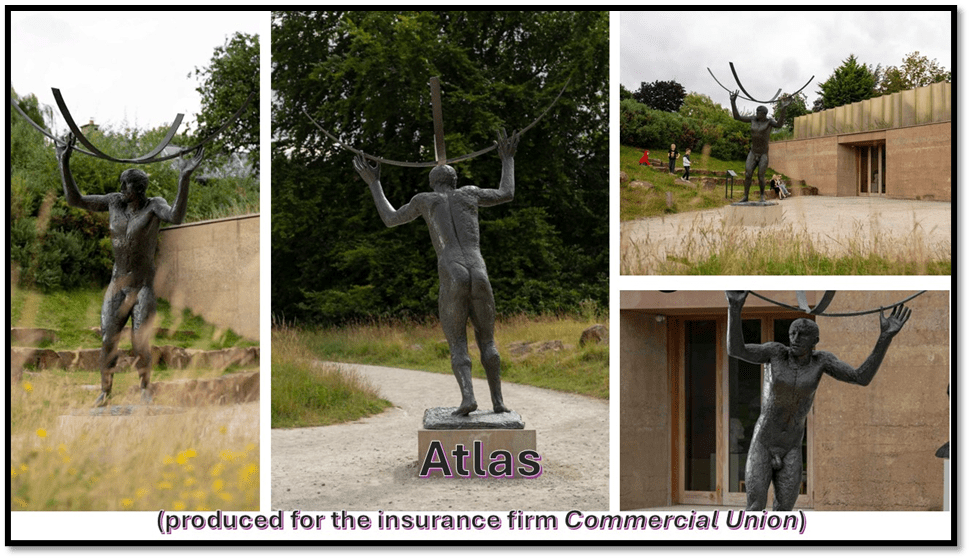

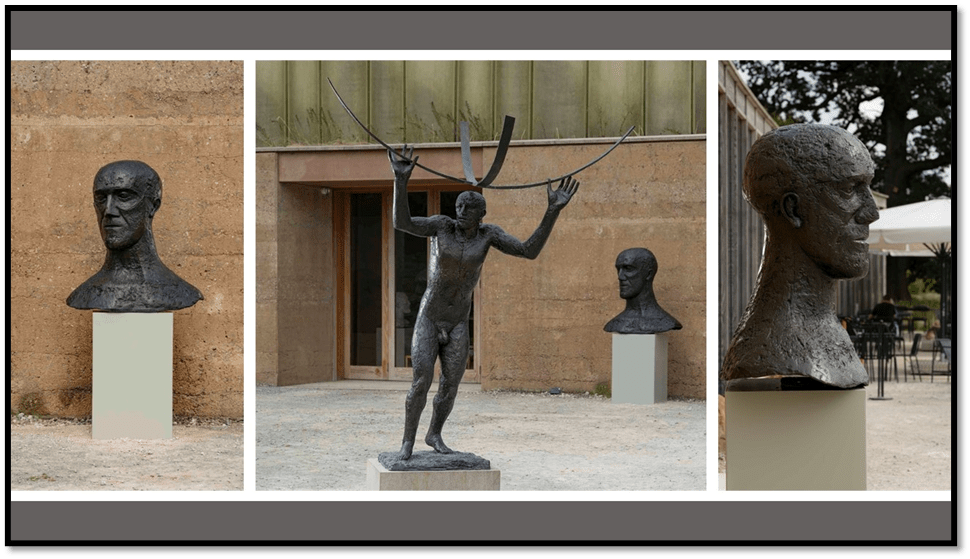

Commercial Union later commissioned as their logo Atlas but her Atlas too is a Frink man first, a myth second. As the YSP website shows Atlas has always been a motif for men bearing the primary responsibility for the administration of worlds. They point out that she adds vulnerability to the mix:

In Greek mythology, Atlas is a figure responsible for holding the heavens aloft. This sculpture combines several themes that Frink returned to throughout her career: strength and endurance alongside burden and vulnerability.

But her Atlas compares interestingly with the Baroque statue fountain, an extreme onparison of course, that she must have known at Castle Howard.

History of Castle Howard webpage picture: https://www.castlehoward.co.uk/visit-us/the-house/history-of-castle-howard

There is no joy in Frink’s Atlas. The world does not shower his ample body with fluid pleasures. He is beautiful but off-kilter, imprisoned by the world he bears which look too much like a straitjacket. He no longer is a man but in role. Was this what Frink saw in men by then? Well that and an insistence on the value of their heads over all other heads, especially female ones. Take the In Memorium II (sic. Frink’s spelling was ertatic) head at YSP, now glancing un-enviously at Atlas .These heads signify vulnerability by their marked skin surface. Her heads started off as Warrior Heads, became proto-fascistic Goggle-Heads and finally merely dissevered organs empty of capability in the body and blank of thought, even if, as everyone says of men whh think themselves superior, dignified.

The maquettes of these in the exhibition are typical. They have no focal point because their gaze is entirely internal, repressing that within that might shake that mask of dignity. They are varied in expression but disguise that, even the one with a beautiful curved upper lip. Their mouths are held tightly shut. They communicate as little as possible – but then, without a body, what is worth communicating, Frink might have thought.

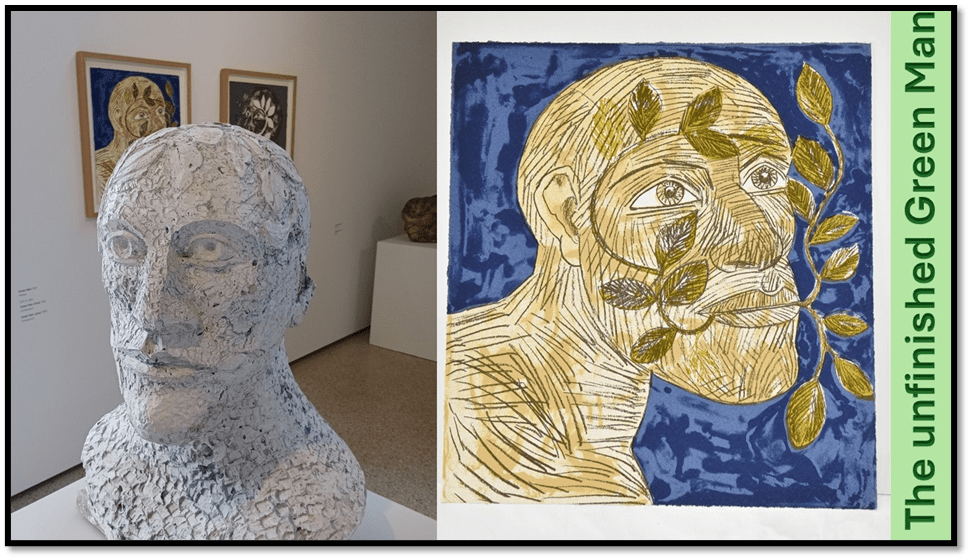

Indeed I suspect that is probably true of the unfinished Green Man.

Her early work revelled in the association of man with nature, mediated by animals of service to men – hawks, horse and dogs. Those dogs are so much better than the men of which they are extensions. Hence perhaps why Frink, despite hating to think of the death of a hunted fox, still supported hunting from her home.

Tomorrow for Danez Smith. I will report back if I visit the Frinks again soon. By the way, its attitudes bear the weight of history, but I loved the Frink biography.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxx

[1] Stephen Gardiner (1998: 177f.) Frink: The Official Biography of Elisabeth Frink, London, HarperCollins Publishers.

[2] Ibid: 218

[3] Ibid: 229

[4] Ibid: 222f.

[5] Ibid: 177

[6] ibid: 177f

[7] Ibid: 194

[8] Ibid: 250

[9] Ibid: 247

[10] Ibid: 157