This photograph of the book , from the review in the socialist newspaper, ‘The Morning Star’, puts the book not next to its author but to people listening ‘to speeches during the Miner’s strike 40th anniversary rally at Dodsworth Miners Welfare in Barnsley, March 2, 2024’. Are these the images we should recall in making an album of the meaning behind the theoretical work and documentation of the history of mining by John Berger. (1)

Since this is the only prompt I can use on my holiday from the heavy stuff and into my passing and naturally accumulated interests, I have to get out the dictionary again, for this question assumes that the word ‘album’is one denoting a collection of recorded songs and music , as indeed it is in most people’s vocabularies in the contemporary world. However, that resulting meaning was only finally arrived at by virtue of some various flips in the implied meaning in the word’s usage during its etymological history.

The older Berger and the posthumous book

As Vocabulary.com states, the word ‘album’ derives from the Latin for ‘white’, used symbolically to indicate a blank tablet upon which no mark has been made. From that beginning, and as the stylus and tablet are replaced by paper in public communication, album referred to a blank book. Such blank books have had various usages described as those of an ‘album’.

These usages have created specialised meanings of the word in various cultures and sub-cultures which describe their particular use of it – the definition in Vocabulary.com mentions the use by German academics to create a book containing autographs of others, a thing we often called, when they were fashionable ‘autograph books’. The most common usage in English and in the UK was for a blank book intended to contain photographs that were souvenirs of past events and of the people participating in them.

The smart phone camera with its apparent endless storage capacity has put a finish to that cultural artifact, though they will exist in most people’s stores of things no longer often consulted.

In interpreting the question for my use I have also ignored the intended meaning of ‘favourite’ as one that indicates the one example of a musical ‘album’ that I most ‘like’. If it works in my answer at all, which I doubt, my use would indicate the kind of album, or record of pictures from the past I most favour seeing. Endless photos of the same people on different holidays is what our family albums are for Geoff and I. We have a stash of these in the bedroom chest, somewhat whinnied away now but sometimes containing momentoes of the past that become poignant, including memories of people no longer living or for other reason, no longer accessible in person.

This is a piece on a book that acts as an ‘album’, it’s white space has given over to recalled words and images from The Miners Strike in the UK over the years of 1984-1985. But I think of it as an album because it is the kind of album I favour; given over as it is to epigram type reflections on the nature of lives under stress and protest against unnecessary oppression driven by top-down power. I have reminisced on that strike in a recent blog on a recent volume of poems called Strike by Sarah Wimbush (see it at this link).

Like a photograph album, this book has a special memory for me in that its introduction mentions an event at which I was present and about which I blogged (see the blog at this link). That event was a commemoration in 2019 at The Middlesborough Institute of Modern Art (MIMA) of the 1989 exhibition of the work of Knud and Solwei Stampe held by Cleveland Arts and for which Berger wrote a statement on ‘Miners’, shared at that event I attended in photocopy by Tom Overton and reproduced in this ‘album’.

The book acts like the perfect album for me as I will go on to show though albums rarely have an introduction. This one does. In it the book’s curators / editors, Tom Overton and Matthew Harle, explain what they are doing in this collection of aphorisms, essays and images that follows; namely these ‘Contents’:

- The piece ‘Miners’ is printed just as it was as it was handed out at the MIMA conference in 2019.

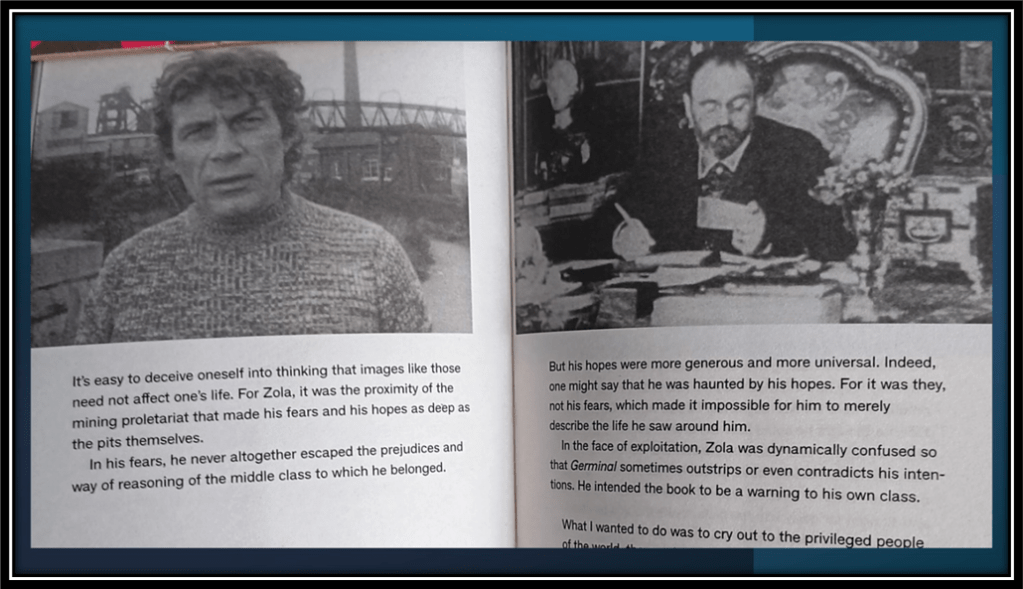

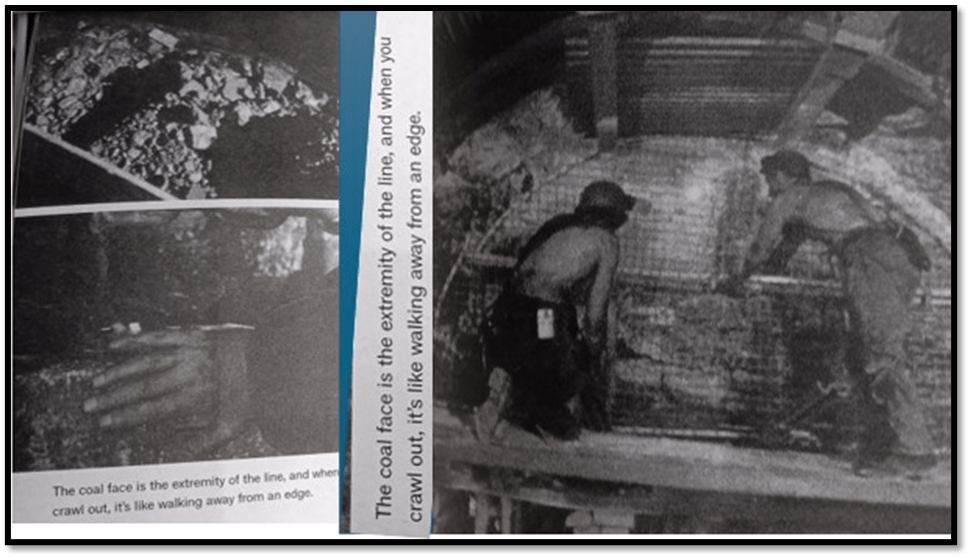

- The TV narrative play script (Berger’s voice-overs) for a documentary he did for the BBC and the Open University (OU), at the request of the Marxist literary critic, and then head of Literature studies at OU, Arnold Kettle. The documentary was meant to introduce OU students and BBC viewers to the issues in the study of Emile Zola’s novel on a mining strike, Germinal, using the BBC’s televised version as a jumping off point. It was filmed at Cresswell Mine, near Bolsover in Derbyshire. The text is accompanied fairly low-quality (by today’s standards) TV screen images with all the original grey grain in them of the time’s TV.

- An interview with a miner entitled Before My Time, in which Berger draws out a picture of the primitive conditions in many pits through the testimony of Joe Roberts. It remains a harrowing read.

- A theoretical essay by Berger on The Nature of Mass Demonstrations, in which he distinguishes different kinds of political protest that are less than revolution, or merely in preparation for it. Mass demonstration like the Miner’s Strike force the state to show its attitude to challenge the power of those in control of it. They will crush it and show their oppressive nature or give in and look weak. In both cases this is all preparatory, in Berger’s judgement, to just revolution.

The only review I found of the book was in the Marxist-socialist newspaper, The Morning Star, by Lynne Walsh (its opening photograph I use above). Walsh is obviously a fan of Berger but not necessarily of the editors of this book, especially Tom Overton, Berger’s biographer (the article says that biography, called Go Closer, will be out this year but it is difficult to find validation of this). She says quite uncharitably of the book that it ‘falls short’. She says further that the ‘slight volume may seek to dig deep, yet it barely scratches the surface’, that ‘the sum’ of its parts ‘manages to be less than the whole’.

Citing Matthew Harle, ‘who has co-edited the book’, Walsh then quotes his explanation of the book form version of the documentary: “Transforming the film into a narrated visual essay slows down an ephemeral work of broadcast into a political meditation.” But having said that she returns to the attack, saying that;

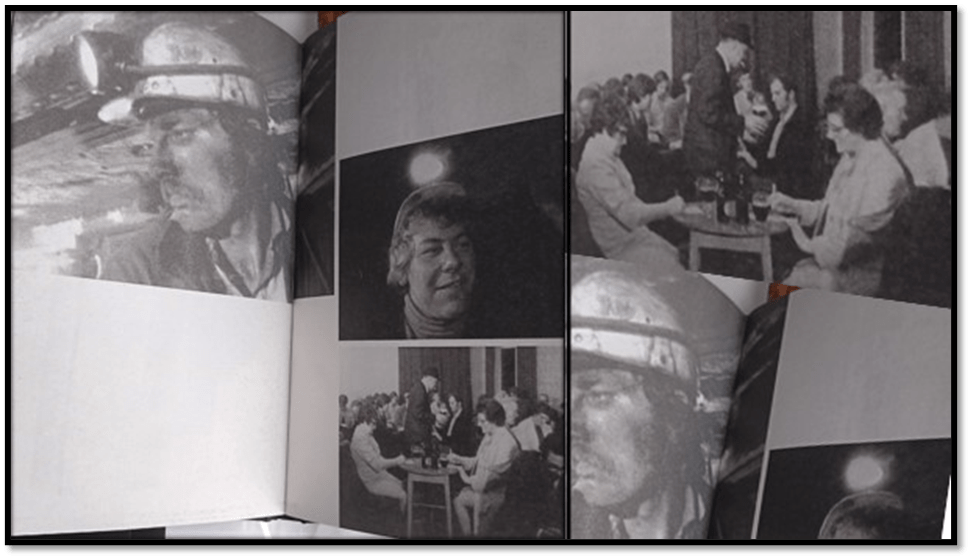

would have been more effective if the stills reproduced well. As it is, they simply do not do the film justice. The editing of images is rather poor, too, with a photo of exhausted miners, staring hollow-eyed into the distance, juxtaposed with a near-indiscernible snap of a social clu’. (2)

Walsh’s tough position may have truth behind it but lacks any sign that she has ever experienced tje world of albums aa working class people have. They do not experience their pazt through tasteful and technically petfect photography, forms that are commodified by the current standards of the media and its resources. They have always looked at their heroes and lost family members through grainier photographs than those in the book and value what the old medium so evident tells them of the fact that these historic heroes and loved ones, though passed away now, were of their time and only reproducible through the media of their time.

To say that we would be better off without the stills and the text in this book just because the images cannot be reproduced to modern standards is to put the commodity value of this book before its use as a prompt to folk and class memory and history. It is moreover an insult to the part of Berger’s oeuvre saved here from oblivion. And to the people who are Berger’s participant witnesses in them,

I am certain about this for every woeking claas ancestor of my own I have come across were or are experienced lookers at images of loved-ones from the past in less than good reproductions of their image. The quality of reproduction does not make them see the persons photographed as in themselves less than worthy subjects of art, as her description makes them sound: ‘exhausted miners, staring hollow-eyed into the distance, juxtaposed with a near-indiscernible snap of a social club’.

And this is why I want to see this book as the kind of album I favour: one that recalls life and makes it relive in its recall. We know it is living because suddenly we realise that we can interpret episodes in life that we thought we knew all about already, differently – we see the humour in its approach to tragedies and vice-versa. And we see the nobility in those thought ignoble, as I do my grandfather when I see him in photographs in a brick yard.

If we do this, this book is a joy; its textual voice-overs most rich in political wisdom and human love. The wisdom of miners themselves is venerated – their ability to neglect the weight of oppression above them in order to survive, whether that be physically in the mine or in a society that pushes them to the depths of misery and makes them bear the cost of the cycles of decline in capitalism. Look, for instance, at how the idea of being at ‘the bottom’ is used in the text below: and the irony in Berger’s face as he realises that tomorrow he will not be in the pit but the man next to him very definitely will.

But the miners he worked with for one day made him realise that, though they themselves made no overt differentiation between him and them, there would always be a gap between them; ‘a gap in terms of experience’. As a result a ‘large part of the miner’s life remains mysterious to me’. (3) But why does Berger say this. I think he felt affiliated to the working class even though his upbringing was far from working class experience – his father Stanley was undoubtedly middle-class. But the gap mattered to him because to forget it is to forget that he was an ‘outsider’ to miners. however hard he might try not to be. They knew their lives better than he.

Berger wanted OU students to realise that because he wanyed them to know that writers, especially middle-class writers, make mistakes if they do not see this gap in experierence. This is how he wanted them to think about Zola’s Germinal. Despite Zola’s sympathy with working people, the gap between he and them was even greater in the nineteenth-century than for Berger, a committed Marxist now in the twentieth. Here we see why Berger’s album had to use ancestral connection of a different sort than those miners allowed him to feel with them imaginatively. Hence Zola has to be an image in this album:

Note how Berger in his text worries out the differences not only between both writers on this page (him and Zola respectively) and the miners they respectively visited, and studied in their own different fashions, but between Zola and him as writers of their times committed to working-class aims for a true democracy in which workers had real executive power. For both of them going underground took them to a coalface they saw as an limit, ‘an edge’, of the experience they understood, And it was an edge they couldn’t get away from fast enough

Make no mistake, Zola would not have raised a pint in Cresswell Welfare Hall or even in the community he knew in Northern France, or seen his fun as gained in the way that Cresswell villagers did with their album pictures of fun events in their social club. He is alone in this page spread, shown looking away from the events in the club concert room, with the families and pets that were all part of the connection of each miner to each other, the pit and the entire community and its album of working-class memories wherein the ‘mine and its history is as familiar to them as the weather’.

And because the writer experiences a ‘gap’ between himself and the miners’ experiences of living day by day, their imaginative writing, in confronting the mysterious and unknown in that life, will reall, Berger asserts, spell out the equivalent of a dream. And this is how he wanted the students to think of Germinal. Of Zola he says that, despite ‘all his claims to be scientific, despite all his research, Germinal is essentially a book about a dream. A dream which is often a nightmare’.

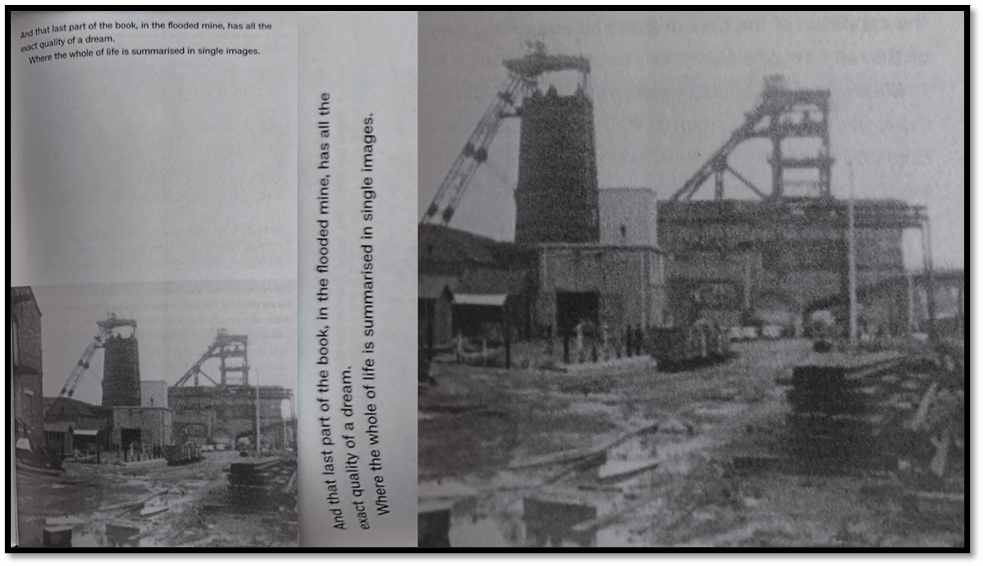

Hence some of the images of this book remain in the text with only an imaginable symbolic relationship to the scenes of pit life. The nightmare aspects were unreal and Berger lists these: ‘the spectre of the mob’, the ‘subsidiary spectre – anarchism’ (in the form of the character Souvarine) and the symbol of the ‘underground sea’ that eventually floods the mine, though it also puts out fires. The whole of the ‘last part of the book, in the flooded mine’ Berger says, ‘has all the exact quality of a dream’. I think even family albums are full of such mysterious unspoken spectres and nightmares , where the ‘whole of life is summarised in single images’.

But look at the picture of Cresswell above – poor reproduction as it is, and can you not see the underground sea seeping onto the pit surface, beginning to threaten it. And like Etienne and Souvarine, there is something of the alienated outsider about how the documentary, from the evidence of the stills of the book, captures Berger as a narrator who is an alienated dreamer who never really joins in with the community. Berger does not smile. He is not shown among friends, or even comfortable in his own skin, unlike the miner next to him and the community in the welfare club.

What Berger needed to insist in his programme is that the true cost of capitalism and its need to ensure the increasing returns that the added surplus value labour itself adds to their capital investment, is that Western capitalists give way to claims for higher wages and mechanised safety in Western mines, o ly because they know they havd the power to eventually close them down and shift capital to a location with cheaper labour, It exploits most in tneze zotuations labour amongst alienated colonial underclasses and/or pre-organised labour. However, images like that below are no longer current and can be misread as racist, although the analysis remains true.

But before we leave this lovely book, an album to favour, we might note that Lynne Walsh does save some praise for Overton and Harle as editors in the end. She finds it ‘rather beautiful’ in their joint introduction that they ”deftly weave Berger’s admiration for artist Josef Herman with his book on a country doctor immersed in the Forest of Dean community’. This is is because the book is also about the contradictions of being a progressive writer. Josef Herman lived the contradiction of being a European anti-Fascist and socialist expressionist adopting a mining community whilst they adopted him, but as a painter he survives only in his influence on others.

Joseph Herman (1953) ‘Three Miners‘

Likewise the tortured relation in A Fortunate Man between a country doctor and a working community leads the doctor to intense depression and, though outside the book, to suicide. In Overton’s view, though Walsh does not pick this up, these experiences and then the making of the Germinal-cum-Cresswell documentary actually led to his greatest work The Seventh Man.

The last-named work is in part about why migrants, and others destabilised by global capitalism,have to keep albums (even if it is only one family photograph) to remind them that life can only now be experienced in capitalism ONLY in a dream conjured up over an album or photo, as more whole and true than their life in a Europe that does not want them.

The Seventh Man is a bleak book – when I was teaching literature I taught it in a literary survey first-year course – and it is bleak not only because it finds wonderful disconnections within ‘the montage of text and image’ but in its building of those disconnections into a perception of global fractures: what were called then the ‘Third and the First World’, capital and labour, and alienation and imagined community in our ideas of communication and solidarity.

Do read this lovely little book.

All my love

Steven xxxxxx

_______________________________________________________

(1) See the article at: https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/john-berger-and-miners

(2) Lynne Walsh (2024) ‘Book Review: John Berger and the miners’ in The Morning Star online (Sunday June 16 2024) Available at: at: https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/john-berger-and-miners

(3) Tom Overton & Matthew Harle (ed.) [2024; 44] John Berger: The Underground Sea: Miners and the Miners’ Strike Edinburgh, Canongate Books.