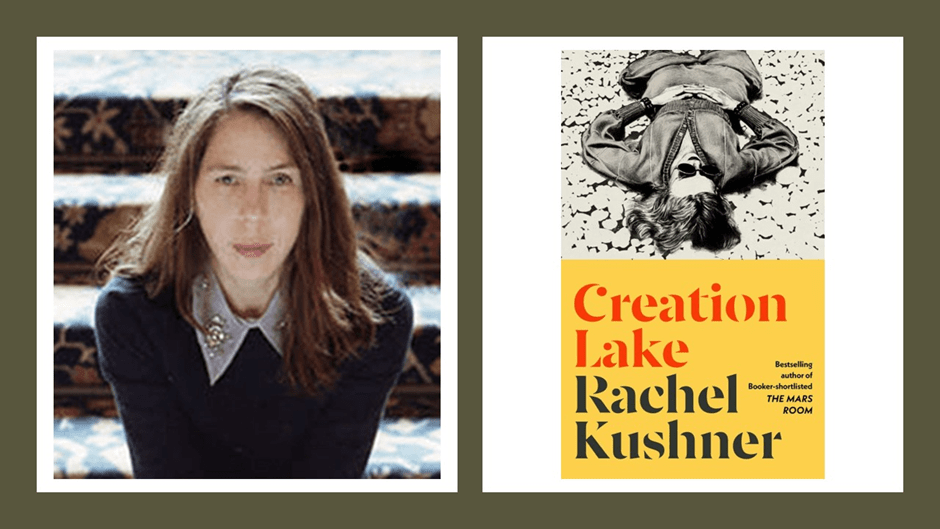

Creation Lake “was the most fun I’ve ever had doing anything in my life” said Rachel Kushner in a recent interview with Lisa Allardice. [1] This is not a review: ‘Close in the name of jesting! / Lie thou there, / for here comes the trout that must be caught with tickling. / — Maria, from Twelfth Night’.

Close in the name of jesting! Lie thou there, for here comes the trout that must be caught with tickling. -- Maria, from Twelfth Night’.

The words above are not really a quotation from Rachel Kushner’s Creation Lake, but it is the novel’s epigram. It comes from Act 2, Scene V of Twelfth Night, which opens with the comic aristocratic brothel-haunting ‘character-drunks’, Sir Toby Belch and Sir Andrew Aguecheek. Aristocratic roughs down on their luck with alcohol waiting to raise a laugh to fill empty lives in this play pan a ‘sport’ or ‘jest’ to entrap Malvolio. The latter is a stuck – up narcissist, no more than a chief servant after all, in class terms.

The English court liked to see plebeians reduced to a laughing stock, for ‘they’ were ‘not of of us’ however high they rose, like Cardinal Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell alike, they thought. The ‘sport’ the feckless aristocrats set up is to leave a letter for Malvolio to see, in fact written by Maria (described as ‘Olivia’s gentlewoman’ so no ordinary servant – a person herself of aristocrat origin) that pretends to be one of love from Olivia and asking to see the servant ‘cross-gartered’, in a livery aping the ‘greatness’ (of social status) that we all know Malvolio wrongly sees in himself and thinks now ‘thrust upon’ him though not ‘born’ in it. The quotation above is, in the play text, interrupted by the stage direction where, after sending the rogue knights into hiding, Maria places the letter for Malvolio to see. The whole point is to put the lower-class snob back into his lowly place. I have never liked Twelfth Night in truth, because to me it has always seemed a play about pretension in aristocrats, jesting with the lowly, putting them in their place.

Maria and Sir Toby plotting

Shakespeare was intent sometimes on pleasing the court of the queen (he was circumspect with James I later) by mirroring its values and this play does that par excellence. In contrast, I do not think that Rachel Kushner aims for us to see Twelfth Night in such a light by using this epigram, even though, in an interview with Lisa Allardice in The Guardian, prior to publication, she says: ‘Creation Lake was the most fun I’ve ever had doing anything in my life’, and her view of the values of the present is something that ought to furnish a tragedy rather than this comedy of errors.

Kushner, from the evidence of the interview, is a hard nut to squash into a category anyway; clearly from a privileged academic background (her parents were academic scientists), her tendency has to been to use the social entitlement she has to explore different kinds of alternative lives – from fast motorbikes to vintage cars, and now drag-racing with her son, Remy, for whom she bought a 1969 Dodge Charger for his 16th birthday. There is serious money behind such a lifestyle.

Kushner has strong Liberal (not neoliberal) political opinions in ways that don’t seem attached to party as such and although intensely liberal in the US tradition she understands why some Republicans love Trump and tries to change the subject when they talk politics rather than drop the people making this preference. She also has, bless her, strong opinions against the Biden alliance with Israel and a belief that rich economies need take a step back from the digital revolution into a less growth-conscious tool-crafted society, where people work with their hands. Sustained work making things manually, she tells Allardice, brings ‘a form of richness to our life that people who just scroll phones and use modern computer technology are lacking’. [1]

A valley in south-west France, where Kushner’s latest novel is set. Photograph: Photographer Chris Archinet/Getty Images in Lisa Allardice (2024) ‘Interview: ‘Writing this book was like a drug high’: Rachel Kushner on her Booker-listed novel’ in The Guardian (supplement) [Sat 31 Aug 2024 09.00 BST] available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/article/2024/aug/31/writing-this-book-was-like-a-drug-high-rachel-kushner-on-her-booker-listed-novel

She also tells Allardice that she prefers the politics of the French valley, the area in which the novel is set and in which she now lives with her artist husband Jason Smith. He is attached to the ArtCenter College of Design. Reticent about political dialogue, she believes America needs to learn lessons from the French turn to ‘what Kushner calls “nativism for want of a better word”, ans versions of the same across Europe, although Allardice does not push her to say in what way we learn from it or what her definition of it is. For most ‘nativism’ is the rise of movements that some feel a better word for is ‘fascism’, or at least revived European-style ‘nationalism’.

Yet, the politics she focuses on in Creation Lake is another rather Utopian form of nativism based on very fancy ideas about forgotten, suppressed and repressed native cultures to which we should return – those of a putative form of the many varieties of a Neanderthal species of human (Thals in the book) – or some fusion of that race within homo sapiens from the time when they collaborated, lived and loved together.

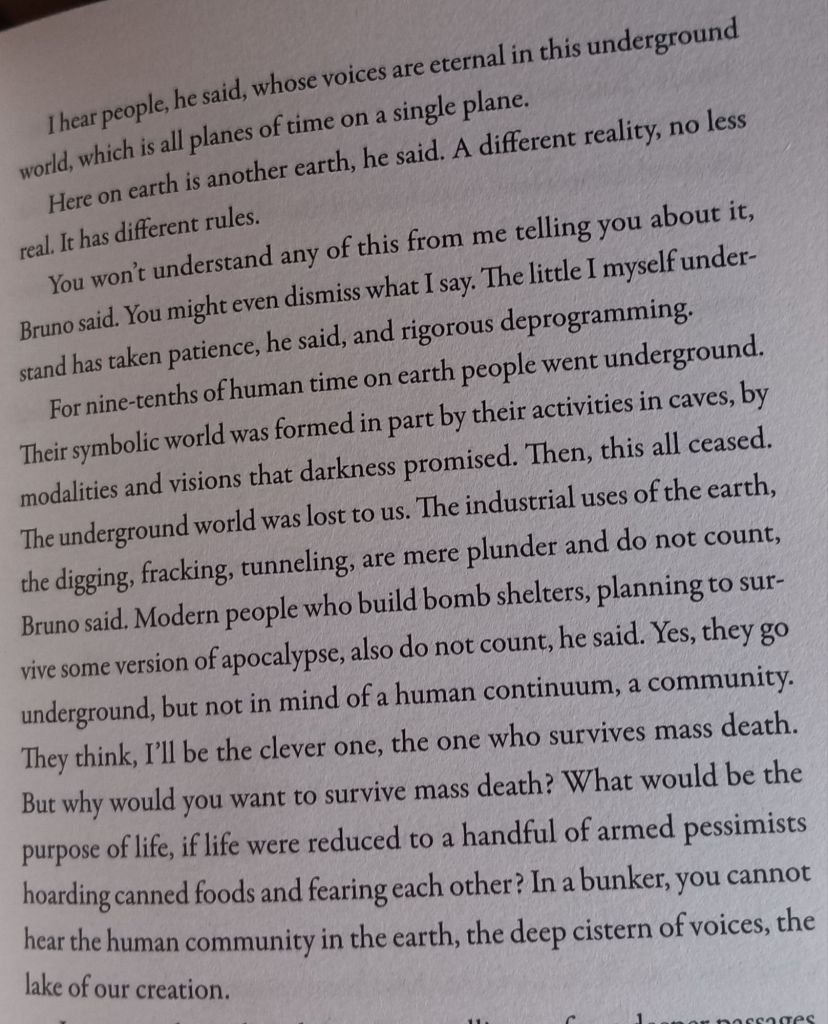

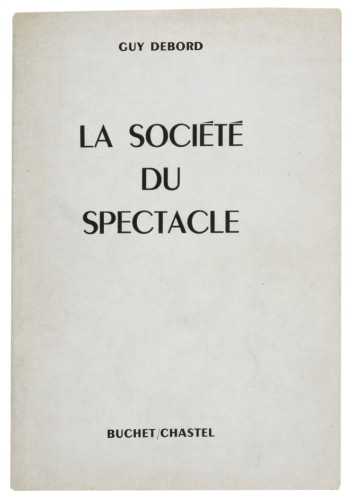

The whole ideological structure is imagined as a creation of left intellectuals from the Paris Revolution of May 1968, especially the situationist Marxist Guy Debord, whose fictive colleagues, Bruno Lacombe and a character who seems a whole lot like John Berger in his turn to the French peasant as the focus of a modern politics, features as a central stimulus in the novel. These are putative ‘nativists’ of a radical environmentally conscious kind. Here is a wonderful passage on Lacombe:

Kushner, op.cit: from page 113

The title of the novel seems taken from these musings. Bruno sits in caves developing his theories from underground evidence of an older suppressed native culture that had been suppressed by the Homo Sapiens, obsessed with technological spectacle and competitive killing wars.

The caves are possibly based on the experience of Kushner’s son Remy, who currently works as a guide in the cave system of the area in which the family live. He is in touch with the ‘human community in the earth, the deep cistern of voices, the lake of our creation’. It is a fabulous politics in the true sense of the word – one pregnant with fable and parable, though that image of a cistern troubles me, recalling not natural lakes but the collected water reserves (‘underground reservoirs’ in effect) beneath the great cities of the East: Constantinople perhaps.

But even here Kushner knows her stuff for the cistern appears to originate from the Bronze Age, though a Homo Sapien historical stage of development in traditional histories) in the hot and dry conditions of ancient Palestine. That Bruno knows that we won’t ‘understand any of this from me telling you’, the rhetoric of its explanation is still beautiful, like that of a refined philosophy, like Debord’s. Take Thesis 17 for insistence of The Society of the Spectacle, whose beauty and irreducibility is induced by members of the Moulinard movement (an invented name) in this book.

Cover of the first edition of ‘The Society of the Spectacle ‘(1967).

The first stage of the economy’s domination of social life brought about an evident degradation of being into having – human fulfillment was no longer equated with what one was, but with what one possessed. The present stage, in which social life has become completely occupied by the accumulated productions of the economy, is bringing about a general shift from having to appearing-all “having” must now derive its immediate prestige and its ultimate purpose from appearances. At the same time all individual reality has become social, in the sense that it is shaped by social forces and is directly dependent on them. Individual reality is allowed to appear only insofar as it is not actually real.

Situationism is now associated with psycho-geography, and psycho-geographical this novel actually is, wherein the geographical is deep vertically as well as on the surface, and socio-geological. Kushner is, you will have guessed, committed to both the intellectual and philosophical representation of scientific knowledge and the history of left politics after the decline of classic Marxism and projections of how best to defeat capitalism and its war machines. In a way, its ambition is much like that of H.G. Wells in that a Fabian left kind of history (and the power to predict differing futures – as in the Time Machine) hangs on a reading of historical origins. But given all that why does Kushner say she had ‘the most fun I’ve ever had doing anything in my life’ in writing it.

Allardice says: ‘A novel about prehistory, “the ultimate love-story of the coming together of the Homo Sapiens and the Neanderthal”, as Kushner puts it, might not sound like everyone’s idea of fun’. We have to take into account, the critic continues, that Kushner tells the story through a genre-mix which puts the historical novel in touch with the ‘noirish’ political spy thriller and has the spy, actually more than that a paid agent provocateur who once worked with the FBI, and bearing the name Sadie Smith for this plot assignment. Her ambivalence and sexual adventures, for the novel comes out of the scandal about how placed security officers often so masked themselves as ‘subversives’ that they formed long relationships with members of what were largely environmentalist groups. Agents provocateurs of course aim to make groups act in a more radical way in order to make them identifiable as criminal and thus more easily eliminated. So even the other story has its dark and serious political side. Allardice cites Kushner, who sounds even more like H.G. Wells here, saying that:

“I wanted to write an ideas novel that’s not boring, an ideas novel that someone can read and read,” she explains. The idea at the heart of Creation Lake is nothing less than “where we came from and where we are going”, she says simply. It couldn’t be more urgent. As Bruno has it: “Currently, we are headed toward extinction in a shiny, driverless car, and the question is: how do we exit the car?”

Attempting to write “a page-turner with long disquisitions on the nature of human history”, was, as Kushner concedes, a bit of “a magic trick”. But it is one she feels she has pulled off, and the judges for this year’s Booker prize agree, putting Creation Lake on the longlist ….

But let’s put the longlist aside, for I share this judgement of the novel’s absolute quality with Booker judges, Allardice and Kushner herself, for I still need to explain why I can’t really review this novel and it relates to Kushner’s literary ambition. It is a page-turner and that is helped by its short ‘propulsive chapters’ as I read somewhere but can’t remember where, but I could not lose the feeling that sometimes its examination of left-green commune lifestyle, the ideas of situationism, the history of medieval Cagot communities (linked to Thals it is argued), cave geology and so on where shifts of register too soon and too often, and could be sustainable only if we believed that the woman behind the mask of Sadie Smith was as widely read and a profound essay writer, somewhat like Rachel Kushner. M John Harrison reviewing the novel in yesterday’s The Guardian says something similar, but he uses it as a means of praising the novel though cheekily adding that we gain the ‘suspicion that Sadie might be a long-form journalist, or that spies and long-form journalists might share some qualities’. It makes for ‘an excitingly complex and fascinating narrator’ he concludes.[2]

My conclusion as I got to about page 310 was that the character-narrator was so ill distinguished from all of the things that were also the novel’s author, apart from the low political ethics and history of turning movements that were in truth progressive (even if socio-economically regressive) into criminals to be picked off by the state. As I read, I felt I was too often shifted from this very unreliable narrator with massive faults readable merely from the text in which she was realised wonderfully into something like the reports she might send her employers (the French government in this narrative), which is believable, to philosophical disquisitions which isn’t. I enjoyed all the elements in this recipe but I found moving on through felt like walking through a mud-slide sometimes, as fast paced narration gave way to essay style. So I skim read the rest. If it gets on the shortlist (out on the 16th September) I will try again but slow up my reading.

But I still have not yet explained the main reason this is not a novel that appeals to me though it is quite self-evidently brilliantly conceived as a narrative and wonderfully written. It has to do with the epigram that I cited on starting. The plotting of Maria, Toby Belch and Andrew Aguecheek is a kind of trifle. The plotting of Sadie Smith is not. It is deadly and, in the end, at the root of all the evils of the modern neoliberal capitalist work. And yet there is something of art considered as ‘sport’ or ‘jest’ in the joy of the novel, and though this mode of addressing the serious has its defenders (it reminds me of George Meredith who defended it in a long essay on On Comedy and the Comic Spirit).. After all using comedy to address themes that are at base deeply tragic – such as the triumph of deceit and appearances over Debordian substance of community, social injustice and ecological extinction – might well be the best means of forcing us to look at these themes in the face. But this novel plays a lot of jests – the sexy and beautiful character to whom Sadie gives a blowjob, Remy, has the name of Kushner’s son, the cave-guide. It all makes me uncomfortable.

And yet how fine is the thinking. Here is a thought I have often had but ‘ne’er so well express’d‘: Well, we can’t all be Alexander Pope or Rachel Kushner. But like Pope, Kushner revels in wit and intelligence, circling round the tragic and almost falling into the vortex of that whirlpool but cannot convince us that emotion that drives change is a thing except amongst the bizarrely eccentric like Bruno Lacombe.

But here is that wisdom, it comes when Kushner speaks of the differences between French, Occitan and the ‘older languages of the Languedoc’:

Did we always have language? We don’t know the answer to this. Linguists try to chart what they call “glotto-chronologies,. they picture language like a tree, with a trunk, The first language, at the base of the trunk being simple and common, what some call “nostratic”. This is a fantasy. But who can refute them? They cannot escape the chains of their telos, the sad idea that they are the logical outcome, the advanced form of human speech, and that what came before must have been simple and crude.

It takes many years of education to learn that the past was not simpler and cruder than the present and that the future will not be less complex nor crude than the present. In fact some people never learn this and begin to treat even their parents as simpler beings than themselves well into middle-age. There is tragedy in this but also comdy, and Kushner knows that too. Hence with me ’tis oft these words get said:

But that this is not the novel for me, or at least yet – I may try again – do not thionk it will not be for the you. The story of Sadie Smith is morally compelling to say the least, and yes, can get you turning those pages.

With love

Steve xxxxxxxxxxxx

________________________________________________________

[1] Lisa Allardice (2024) ‘Interview: ‘Writing this book was like a drug high’: Rachel Kushner on her Booker-listed novel’ in The Guardian (supplement) [Sat 31 Aug 2024 09.00 BST] available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/article/2024/aug/31/writing-this-book-was-like-a-drug-high-rachel-kushner-on-her-booker-listed-novel

[2] John M. Harrison (2024: 51) ‘Deep cover’ in The Guardian Saturday supplement, Sat. 07.09.2024, 51.

2 thoughts on “‘Creation Lake’ “was the most fun I’ve ever had doing anything in my life” said Rachel Kushner in a recent interview with Lisa Allardice. This is not a review: ‘Close in the name of jesting! / Lie thou there, / for here comes the trout that must be caught with tickling. / — Maria, from ‘Twelfth Night’’.”