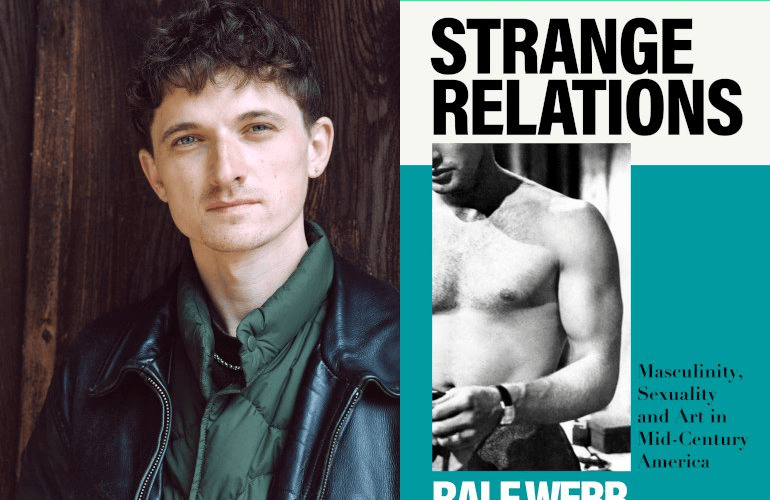

When Kathryn Hughes reviewed Ralf Webb’s (2024) Strange Relations: Masculinity, Sexuality and Art in Mid-Century America, London, Hodder & Stoughton in an otherwise highly positive review she picks out the necessary negative, in order to prove her credentials as a critic. She says that Webb ‘feels obliged to include chunks of plot summary’ (of the literary works treated) ‘that inevitably tend to drag’. Hence, she she suggests he ‘attempts to pick up the pace by deploying present tense – “Tennessee’s been through several weeks of hell” or “Cheever lifts a razor to his neck”‘. These attempts she says ‘feel contrived’.[1] Apart from the fact that Hughes first example does not use present tense at all, just an idiomatic continuous past tense ( for ‘Tennessee has been through’) Hughes is I think missing a point, that this retelling of related stories – oft demanded by publishers from writers in order not to exclude readers who do not know the story of certain works dealt with in literary-historical books – is part of the art of the book. It’s title is part of its propose and drive – It is a book that ‘relates’ to us already published stories, stories about their original writers and their thematic contents in a strange manner, in at least two ways – by revising and reviewing how we ‘relate’ a story and, in part to the same end, making ‘strange relations’ between these things and people, such that the queerness of the book lies in the relationships between its stories. In my reading of it, at least, this is its strength, though it is stronger in relating stories about the writers it concerns than of retelling narratives taken from their published writing, and in that sense Hughes might be correct in part.

But I think it is possible to feel put off from reading yet another book about ‘mid-century’ writing in the USA, which are numerous despite the relative paucity, as Webb points out, of work on John Cheever, and the increasing decline in interest in Carson McCullers. [2] In this book, the relationships – conceptual or based on real friendships or chance connections (the best of the latter is where James Baldwin speaks on the same platform as John Cheever at a literary conference) – are at the core of our concern. Of the real friendships, the choice to tell the story of Tennessee Williams and Carson McCullers in the same section prefaced by a photograph of them together, is the most revealing and vital way of queering their mutual stories around a shared concern about the nature of ‘masculinity’ as it was indeed spoken of and related to by others too in the mid-twentieth century in the USA.

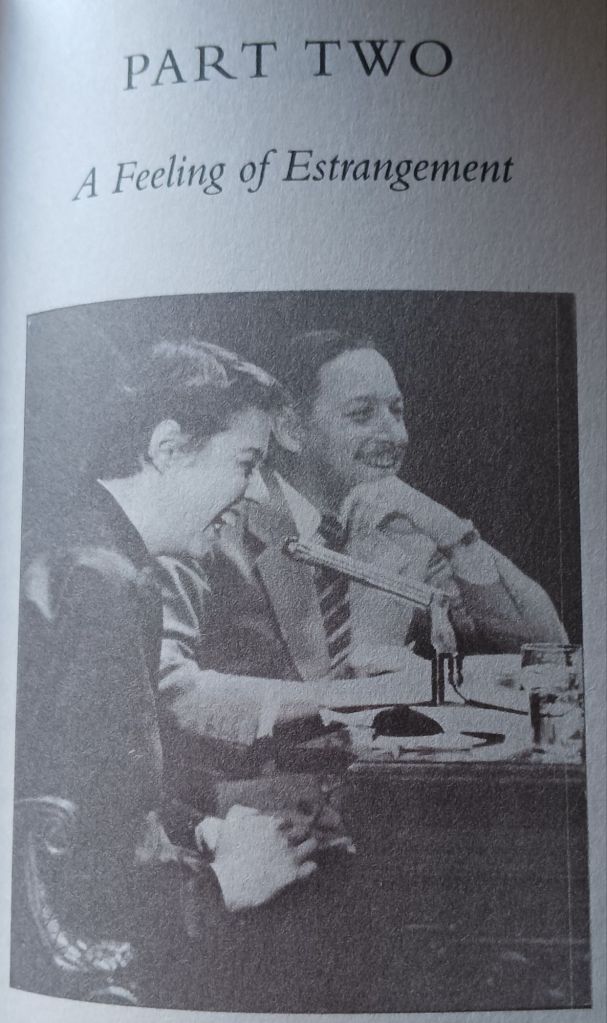

There is no attempt in this book to homogenise theories of sex / gender in its chosen period – and theories of androgyny (via McCullers devotion to Havelock Ellis) rub against articulated self-selection of sex/gender positions as well as psychosocial determinations, in Freud and others. Beautiful nuggets of data are thrown up in the process such that Freud was able to recommend that his queer patients read Havelock Ellis rather than himself to feel better and stronger about their chosen sexual identity, even though he knew better than most that their explanations of the ‘aetiology’ or ‘causation’ of homosexuality differed enormously. I loved the bracketing of Tennessee Williams and Carson McCullers as I have suggested already, for it prefigures the alliance of trans, gay liberation and queer theory at the nodes of its coming together later in history – the first two notably at Stonewall. Yet, it was perhaps the Stonewall generation of queer liberation that perhaps signaled the end of the huge reputation for bold discovery in the arena of sexuality of Carson McCullers (perhaps terminally) and Tennessee Williams, until recently.

Carson and Tennessee from Ralf Webb, op.cit: 69

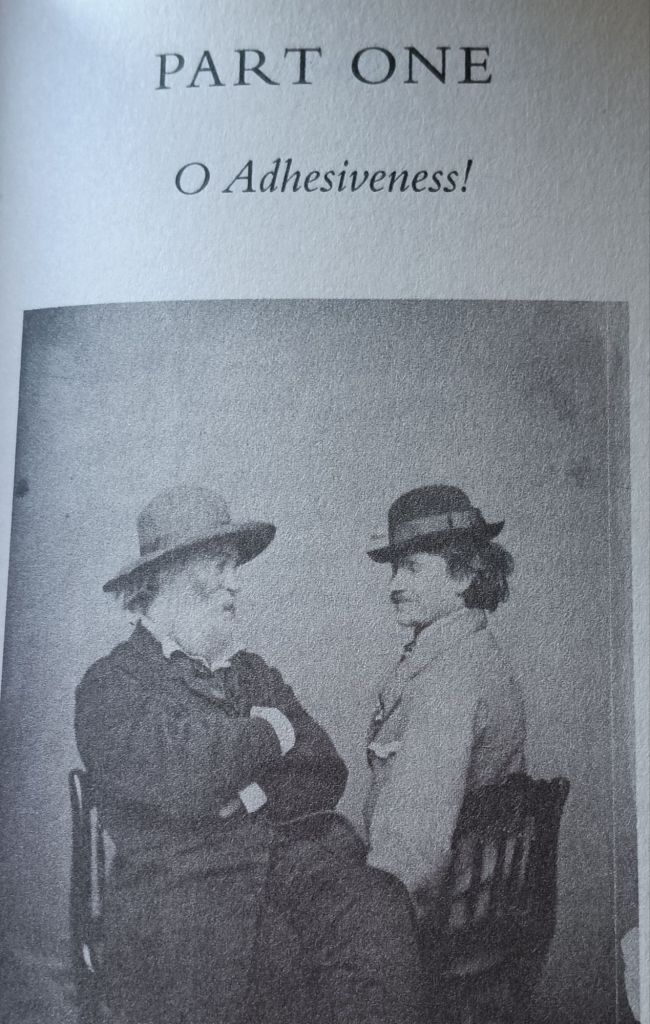

Perhaps though the boldest stroke in a book purportedly about mid-twentieth-century masculinity is to start the book with Whitman in another era, and with the relation of stories about a photograph in which the relation of two men is considered strange, so much so that the reaction of others in naming its strangeness of relationship convinced Whitman at some level of conviction of its strangeness to consider it a ‘strange relation’ too. when I say ‘at some level’ I mean mainly either as a public compliance or deeper statement of nuanced self-relationship. The photograph and the brilliant ‘analytic narratives’ it fosters for Webb to collect and re-relate are clearly more than tangential to the whole book, and shine as its heart of gold and silvered fault-line of rupture.

Walt Whitman and Peter Doyle – detail of Ralf Webb op.cit:17. The stories related about responses to it start on ibid: 22. Webb is brilliant on the theatrical proxemics of this photograph.

The glue (conveniently enough) to mend those ruptures is precisely one that Whitman used himself, and which Webb considers essential to his stories relating the subjects of his book right down to the radical belief in the need to rejuvenate a whole range of potential for love (not exclusively with a sexual potential in them) between men in James Baldwin, about whom Webb is brilliant. The concept in Whitman has that unfortunate fortuitousness (the latter for those who like sexualised associations) of being called by him ‘Adhesiveness‘. There is nothing new in the discovery, though the choices of story chosen and their connection is radically Webb’s own, of the import of the concept of ‘adhesiveness’ to any later formulation of male bonds that are not merely exclusionary homosocial ones designed to mask misogyny in hetero (- and homo -) normativity. What is new I will immediately repeat, in order to reinforce the point, is Webb’s selection, clustering and relating of the stories! Webb’s readings are so exquisite I can’t add to them and so won’t. Suffice to say, his Whitman is my Whitman, for some time to come.

Likewise I gasp at the rescue of Williams from the gay liberation critiques. I wish I had read him before I wrote about Thom Gunn (in the blog linked here) for what Webb shows us in the achievement of Williams is precisely what the radical masculinist perspective of Thom Gunn lacked, fractured as it became as he aged painfully and sadly, for that ideology had little room for aging or less than physically attractive men. There is, Webb shows me, something of beauty and novelty in the character of the poisonously misogynistic Big Daddy in Cat on A Hot Tin Roof, something more than hiding queer themes under gender-crossing (for supposed self-censorship purposes) in A Streetcar Named Desire. And beyond those obvious classics, I now know I will learn a lot from reading plays of his I have neglected like Summer and Smoke, Small Craft Warning and Camino Real.

I have read no John Cheever, even though Olivia Laing’s book on his alcoholic literary adventurers once tempted me, but will now. In that way I needed some of the plot summaries Hughes finds dulling. They are not so exhaustive that they do not whet the appetite for the real thing, making it clear that behind the stories is a voice you need to try and hear as it speaks for itself. His case for the novel Franklin is underplayed, but makes me feel I should start with that.

Of James Baldwin I could not get enough. I will read him again, when I have finished Colm Tóibín’s new book on him at least, but I am reading that NOW. Here books by Baldwin I read, at the time when they were culturally ‘hot’ like The Fire Next Time , I must read again for its contribution to the analysis of intersectionality is clearly seminal, arriving at a time before people even thought of intersectionality or queer theory. Moreover, it appears that Baldwin was not not merely fiery about his Black Movement politics and closeted about those for the gay movement (for instance the only thing ‘closeted’ about Giovanni’s Room is that the male queer characters are both White) but cautious about making over-easy analogies or simplistic theories of ‘double oppression’ because he realised that white queer men could be racist just as he knew for certain that Stokely Carmichael was misogynistic, homophobic but a necessary revolutionary force nevertheless.

Baldwin’s critique against Carmichael was that he was immature. For Baldwin, love and maturity mattered, Webb shows us, and, for Baldwin too, love and maturity enabled the crossing of boundaries, and the queering concepts of race and sexuality into some eventual equalities in diversities. He was wise and mature enough however to realise that none of that would happen without a revolution in thinking, especially about the capacity for love in male bonds. And this takes us back to ‘Adhesiveness’, with the capacity to lose the ugly word. The best formulation of it as a concept comes art the end of the treatment of Williams and McCullers. This is as beautiful a story and a piece of writing as in the writers themselves. Start reading from ‘These men are chained ….’.

Ralf Webb, op.cit: 152.

The dream of communion between men that is beautiful is not in this formulation misogynistic, nor homophobic or ‘homosexual’ as such, though it is queer. Nor is it ‘cis’, for McCullers saw themselves as one of these men we learn from the book. It is a beautiful dream but not in the Utopian sense, except in the idea of a revolution that is cognitive, affective and about the reevaluation of the necessity of distance from the senses has not yet finally been lost from our meaning of what we think it means to initiate a revolutionary programme of change.

Do read this book.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxx

______________________________________________

[1] Kathryn Hughes (2024:50) ‘Brave new queer world’ in The Guardian Supplement (Sat. 10.08.2024), 50.

[2] Ralf Webb (2024: 289f.) Strange Relations: Masculinity, Sexuality and Art in Mid-Century America, London, Hodder & Stoughton

4 thoughts on “I think a lot can be learned by just ‘relating’ stories. This is is a short blog on Ralf Webb (2024) ‘Strange Relations: Masculinity, Sexuality and Art in Mid-Century America’”