The fratricidal protagonist of his novel ‘Falconer’ (the name of the prison setting of the novel), Ezekiel Farragut eventually leaves Falconer. Though a laundromat shop-front he examines the ‘bull’s eye windows of drying machines’ in which there are ‘clothes tossed and falling, always falling – falling heedlessly, it seemed, like falling souls or angels if their fall had ever been heedless’.[1] This blog is a comment on John Cheever (2014, first published 1977) ‘Falconer’.

I turned to read Falconer very recently. It is the first work I had read by John Cheever and I had been persuaded that I must read him by Ralf Webb’s new 2024 book, Strange Relations: Masculinity, Sexuality and Art in Mid-Century America (read my blog on the book at this link). In that blog I wrote:

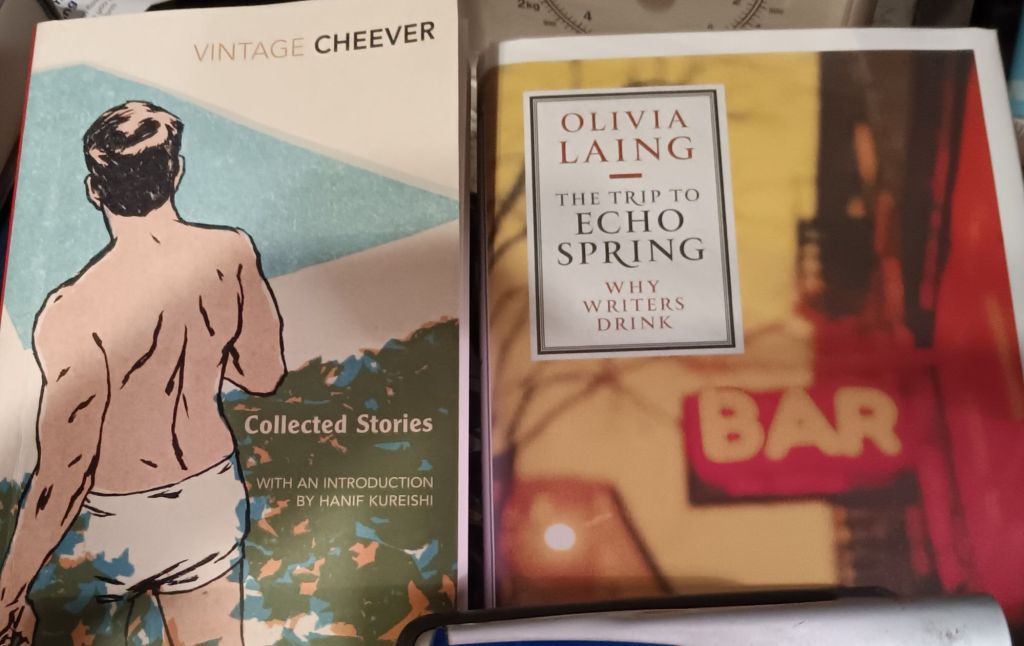

I have read no John Cheever, even though Olivia Laing’s book on his alcoholic literary adventurers once tempted me, but will now. In that way I needed some of the plot summaries Hughes finds dulling. They are not so exhaustive that they do not whet the appetite for the real thing, making it clear that behind the stories is a voice you need to try and hear as it speaks for itself. His case for the novel Franklin is underplayed, but makes me feel I should start with that.

Hence this is my attempt to begin to hear the voice of a novelist, or of his character / narrators, such as Farragut. The blog is mainly on thoughts about the way stories are told by Cheever, or at least as far as reading only Falconer (and now a couple of short stories) can begin a process of thinking about that question. I have returned to Olivia Laing’s 2013 book The Trip to Echo Springs: Why Writers Drink, to start off my thoughts for I remembered her saying, though I still did not read any Cheever, that ‘she would judge ‘The Swimmer ‘among the finest stories ever written’. What I had forgotten was that she thought so (it seemed to me then) merely because it ‘catches in its strange compressions the full arc of an alcoholic’s life’. [2] It was, she had already said ‘about alcohol, and what it can do to a man; how conclusively it can wipe out a life’. [3]

Those definitive descriptions outweighed the poor shoots of any interest in reading him more than would a whole ton of wet cement poured on a ‘darling bud of May’. But, having read Franklin I returned to the story – and what a fine story it is, without doubt, in my judgement too, one of the ‘finest stories’ I have ever read. Although about alcohol’s effects, it is so in quite a different way than any other story I have read – more innovatively so than Amy Liptrot’s The Outrun, about which I said something similar in my recent blog.

In it Neddy Merrill aims to swim the length of many pools in his neighbourhood via a serially connected watery path to his home from a party some miles away. Thematically, Laing rightly insists, it does tell the story of the arc of alcoholic decline over different time durations – a day, a life, a symbolic type – and does so from within the illusions themselves of the user of alcohol in order to capture its putative benefits and illusions as they inhabit human minds. Those are the imagined glories of omnipotence, self-admiration and transcendence of the everyday forms into which time and space are organised, especially those rituals that record and validate the reality of human aging and the physical decline of the body. In doing so, it also registers how those illusions become queried and fail, when they break their promises or threaten so to do.

The story is told in the third person but the point of view is intimately that of Neddy Merrill, and registers it the forms of the things it brings to our notice. Notably it emphasizes effects of time passing. Narcissists hope to see their time as a triumphant progress of the ‘legendary hero’ to whom the ‘day’ belongs, for after all, in prospect: ‘The day was beautiful and it seemed to him a long swim might enlarge and celebrate its beauty’.

That legendary hero has various forms but they are all in the end forms of the hero lauded by his peers and inferiors: ‘a pilgrim, an explorer, a man of destiny’ surrounded by those ‘friends’.[4] Adventurous beginnings seem to be ever ours in the illusion of an alcoholic, at least they are in the prospective story of his coming day that Ned believes in at first. Cheever’s prose makes it clear in a few stunning sentences that Ned finds it difficult to differentiate appearance from the reality of countable years of his actual age (he can acknowledge his age but discounts it having an effect on his capabilities or in the eyes of others):

He was a slender man – he seemed to have the especial slenderness of youth – and while he was far from young he had slid down the banister that morning and given the bronze backside of Aphrodite on the hall table a smack as he jogged toward the smell of coffee in his dining room. He might have been compared to a summer’s day, particularly the last hours of one, and while he lacked a tennis racket or a sail bag the impression was definitely one of youth, sport, and clement weather. [5]

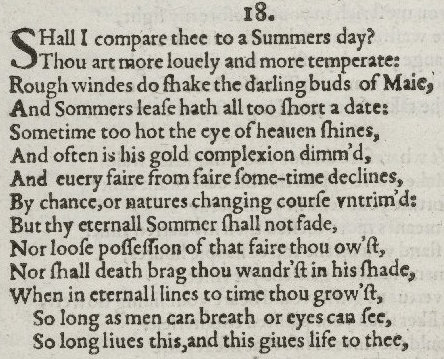

This is remarkable prose, whereby slenderness – which as thinness will become a more ambivalent trait in an older man – strains towards a critique of the masculinity that Ned aspires to. He strains to counter fleshly love (or its Goddess in female form at least) with a roguish smack on its bum as a sign of his superior right over the sexual body. Those superior ‘rights’ assumed by toxic masculinity however are increasingly less acknowledged as Ned becomes the more exposed to eyes and the mirror of his friends and acquaintances aging and remembered experience (for they seem increasingly to remember more about him than he himself does). A begged drink at each pool he swims in as he imaginatively creates the ‘River Lucinda’ has less and less rejuvenating effect and Ned is repeatedly the more exposed to humiliating reflections on the life he is in fact living. We readers realise that only very slowly and not in full till the last sentence of the story. But what made me see its brilliance most was the ironic use of the phrase from Shakespeare’s sonnets: ‘He might have been compared to a summer’s day’. Here is the source in Sonnet 18.

It is a wonderful poem, of course, addressed to a beautiful young man, but it makes it clear that similes belong to poets and that they are not always true comparisons – after all some ‘summer’s days’ are not just beautiful, they might be bothersome because ‘too hot’. Poets ought to know best it smugly sighs that days pass like other temporal units and that therefore if you are ‘like’ a summer’s day, so too will your beauty like ‘every faire’ pass away as every other of its type ‘some-times declines / By chance, or nature’s changing course untrim’d’.

It is only because I am an exceptional poet, says Shakespeare and am bound to persist through time, that the young man’s ‘eternall Sommer shall not fade’. It was a bold move of Cheever to invoke this Sonnet but a telling one. For Neddy Merrill too is exposed in the duration even of a very short story, to processes by which he well might ‘lose’ much of that he values, and might indeed have forgotten that he has already lost, ‘possession of that faire thou ows’t’. The last thing we know he loses is his ‘home’ (to which he thinks he’s heading), his children and wife. Returned like everything we mortgage on fslse promises, back to the cruel system which is the fallacy of progress along the arc of the ‘American Dream’.

The story continues in the increasing presence of environmentally physical markers of passing time showing the ‘summer’s day’ more declined (physically and ethically) than Merrill had thought. The light fades and the scenes he sees are dark, racked with polluting traffic and waste, disrespect for others and those who have become the ‘victim of foul play’: ‘Standing barefoot in the deposits of the highway – beer cans, rags, and blowout patches – exposed to all kinds of ridicule, he seemed pitiful’. [6} The decline of the daylight and the change of the conditions seem emotionally taut. The elderly Hallorans – their elective nudist bodies still preferring nudity even in older age – commiserate with his ‘misfortunes’: the selling of his home and the fate of his ‘poor children’, and now, as his trunks seem loose on him, he feels his body not ‘slender’ but depleted (age hangs behind the markers invoked but dare nor speak its name):

… he could have lost some weight. He was cold and he was tired and the naked Hallorans and their dark water had depressed him. The swim was too much for his strength …. His arms were lame. His legs felt rubbery and ached at the joints. The worst of it was the cold in his bones and the feeling that he might never be warm again. Leaves were falling down around him …’ [7]

Just as ‘slenderness’ is not youth, though it has this appearance, as Ned reaches nearer a home he in fact does not have in his possession any more and a realisation of his family’s fate, so does he physically accumulate signs of age WITH the ‘summer’s day’ fading into an undistinguished night. That leaves were falling suggests that summer too is ending – or that it might never have been a summer’s day at all, and that too was an illusion. And those falling leaves will resonate for me too in Falconer, though the metaphors there are newer and more genuinely frightening reflections on past literary motifs of the Fall of ‘Man’. Just as Ned Merrill’s story uses Shakespeare’s warning to a young man – that we all pass , our beauty first – the later novel will take Milton’s sense of what a generlised sense of ‘falling’ will mean to humanity.

Shakespeare suugests to the young man in his poem that instead of frail beauty he should take the proferred love of a poet instead who can hold illusions in the certainty of his endurance as a writer. Cheever in using Shakespeare thus was then, I realised, a highly ambitious writer. He may write of alcoholics and alcohol as a subject but his aim was to nail the time thing, like so much else in literature. And the same might be said of Ralf Webb’s preference for Cheever as a writer about queered masculinity. Great writing is never about a topic of socio-political discourse alone, wirhout placing it in the dtead maw of Time to test its durability.

In pasing on though it is worth citing that Hanif Kureishi, a very good writer, in his introduction to the Vintage edition of Cheever’s stories, says one of Cheever’s best is The Country Husband, which does indeed seem in its ironical structure to conclude silently, as Kureishi says, that it makes sense to say: ‘Where then, might a suffering person turn, if not to the bottle?’ [8]

Except that logic is the ‘logic’ of a drinker. Cheever was one such but he still, I think, knows writing might reveal in a glass darkly wonders alcohol cannot sustain. Francis Weed’s (the protagonist of the story) psychiatrist’s recommends the equally unsustainable object of ‘woodwork as a therapy’. There is great and mysterious play of the imagination in the end of that story (though it is more of an acquired taste than ‘The Swimmer’): ‘Then it is dark; it is a night where kings in golden suits ride elephants over mountains’. [9] The play in this sentence is of ‘imaginary heroes’ (as with Ned Merrill) again (although this one seems to be the romantic version of Hannibal of Carthage). Understanding the socialised male’s desire for such a romanticised masculine identity is precisely what Cheever’s writing might be about, and writing is a better way of arriving at such understanding than the illusions of booze.

This is where Ralf Webb almost takes us in his book. He sees Falconer as a deep ‘consideration of same-sex desire” and I think his interest is spot on in a parable told by one of the inmates of Falconer named The Cuckold (because he murdered his wife who had made him a ‘cuckold’) about his one love engagement with a man. The imagery of swimming is, as Webb shows more common in Cheever than its appearance in ‘The Swimmer’ (though I must take Webb’s word for that) but this is how The Cuckold speaks of Michael, the man he fell in love with:

Michael was so gentle and affectionate, he seemed to move through reality’like a swimmer through pure water’, and though the Cuckold had long believed there was something ‘strange and unnatural’ in the image of two men being affectionate with each other – embracing, kissing, having sex – after sleeping with Michael he concludes that this is not the case. the only strange and unnatural thing is for a man to be alone.

That is an appropriate conclusion but it does not connect to other issues about the treatment of same-sex love in stories that don’t get written, but by Farragut notionally in Falconer, notably that of the lonely sexual adventures of ‘the Valley’. That place is a space around a urinal trough where men masturbate alone but together in a group whilst obeying rules not to to touch each other, except the waist and shoulders of an immediate neighbour in line on the trough, and only very surreptitiously glancing at any one of these near neighbours. Webb thinks this an image ‘haunting, comical and beautiful at once’ but that is not I think what Farragut’s thinking tells us. [10] That thinking turned into Cheever’s writing, tells us that though there is no ‘remorse or shame’ in him or other men, the Valley is a symbol of the ‘utter poverty of erotic reasonableness’. For what is the ‘target’ of the erotic? The ‘target was the mysteriousness of the bonded spirit and flesh’. [11] This ‘bonding’ is precisely what the Valley (surely the Valley of Death) rules or regulates out in the name of the ‘masculine’.

I only know from Webb however that writing Falconer was based on Cheever’s decision to voluntarily (without pay that is) teach writing at the Sing-Sing Correctional Unit from September 1971, near the home (he called it Afterwhiles) of him and his wife, Mary. In his writing course, the aim would be “making sense of one’s life by putting down one’s experiences on a piece of paper”. He explains to his learners that ‘narrative is a synonym for life’. [12]. In my view, Cheever here explores how, even in prison, we might reach a target of ‘the mysteriousness of the bonded spirit and flesh’, the word made flesh in an imagined social eroticism embodied if only in prison writing, and making male-only experience that was not regulated by the prohibitive rules of an ideological masculinity and its ‘rules’. Social writing might replace the ‘iron’ of a trough from an embodied recipient of sexual exchange even if only enduringly in imaginative writing.

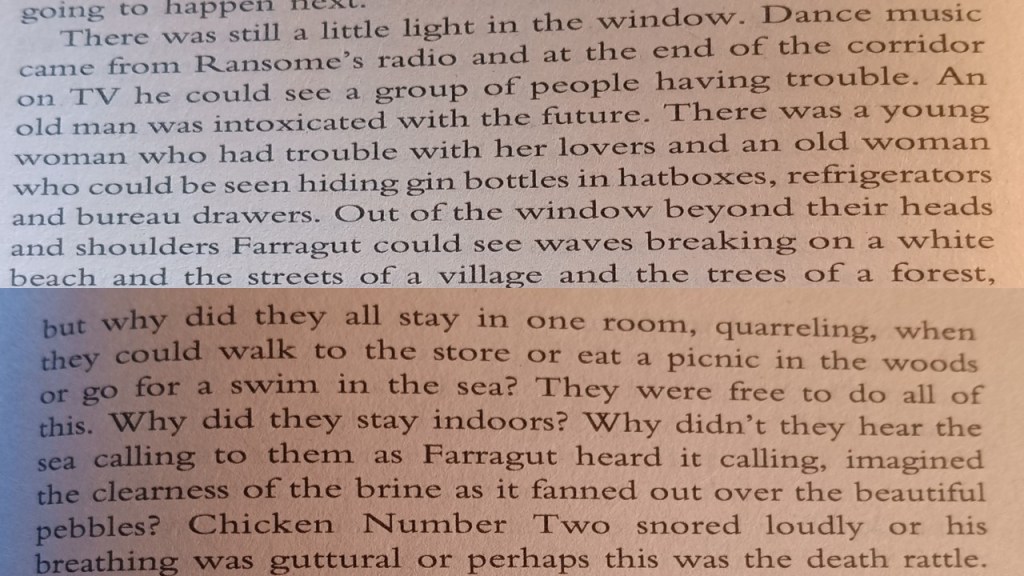

The writing in the novel about Farragut’s disappointment at the kind of sexual regulation chosen by inmates extends to their disembodied preference for communication of human stories by radio, tannoy or TV, which they ‘choose’ [or cooperate in having chosen for them] even when their limited choice becomes even more constricted, as in this stunning paragraph: [13]

What kind of prose is this? It comes from the scene where Chicken Number Two is dying, a death that Farragut will use to his advantage, but it relates to Farragut’s frustrated disappointment at a culture offered to the imprisoned, as perhaps modernity imprisons all of us metaphorically, in a world lived vicariously through an all-consuming media version of people’s lives that haunt radio, TV and (were Cheever alive now) the internet as social media. This culture stultifies bodies, minds and souls by keeping people inside (rooms, houses, institutions like work); even inside their own lives in not sharing them with others, This world is full of hoarders – of trouble, gin bottles and the enclosure of their own breath. What Farragut imagines is exercise and beauty outdoors – another version of the ‘bonding of spirit and flesh’ to which the rest of the world is like Chicken Number Two’s guttural breathing of his last breath – in another Valley of Death.

But such bonding only comes when experience is not allowed to pass and dissipate but its living colours are captured in writing. Hence the import of dreams in Falconer. If left to human indolence ‘the instant’ we wake, as Farragut ‘woke’ after one such dream, ‘the brightness of the dream’s colors were quenched by the greyness of Falconer’, That they survive is because they are written. This is allegorised in the dream. It takes place on a ‘cruise ship’, a place where he is ‘idle and a little uneasy with his idleness’, but where he plays deck games. The cruise ship crashes on a beach and burns beautifully. Farragut though is saved, for a schooner had come to take him off the ship, a schooner owned by nobody he knows. [14] That schooner is the distance required to write up his dream, a place to stand, witness and reflect – the very definition of writing.

The writing in Falconer is complex – reading it is not always easy. The shifts in the story, often guided by shifts in dialogue, throw up many symbols that are difficult to interpret but to which people, especially Farragut, give weight, such as the diamond he seeks from the prisoner Bumpo in order to construct a radio from the very idea of Marconi’s radio’s prototype. The diamond can cut through the ‘Gordian knot of communications’ that complicates the strategies of politics on either side of prison life. It will ‘save the world’ and Farragut wants that because he believes in the ‘inestimable richness of human life’. [15]

I don’t understand that symbolism and neither do those it is ‘communicated’ to in Falconer. My best guess is that they are there to show how meaning can be increased by reflective discourse, the thing that becomes writing and is the only alternative the imprisoned men have to merely staying in and loving prison life for its very meanness towards living. Chicken says staying in prison is the only sensible position because out ‘in the street everybody’s poor, everybody’s out of work and it rains all the time’. [16]

But Prison is a metaphor for death precisely because it robs men of the ability to stand up and be counted as amongst the living. Prison is a dark place like ‘some forest’ but on a winter’s afternoon’. It is at least when it is not it is merely grey. Farragut fantasises about it as like the diagonal light cut into by either iron bars or trees: it is a powerful visual image that emphasises not the sectioning of space but its mysterious largeness when all has become blank like a blank page: ‘where a succint message was promised but where nothing was spoken but the vastness’.

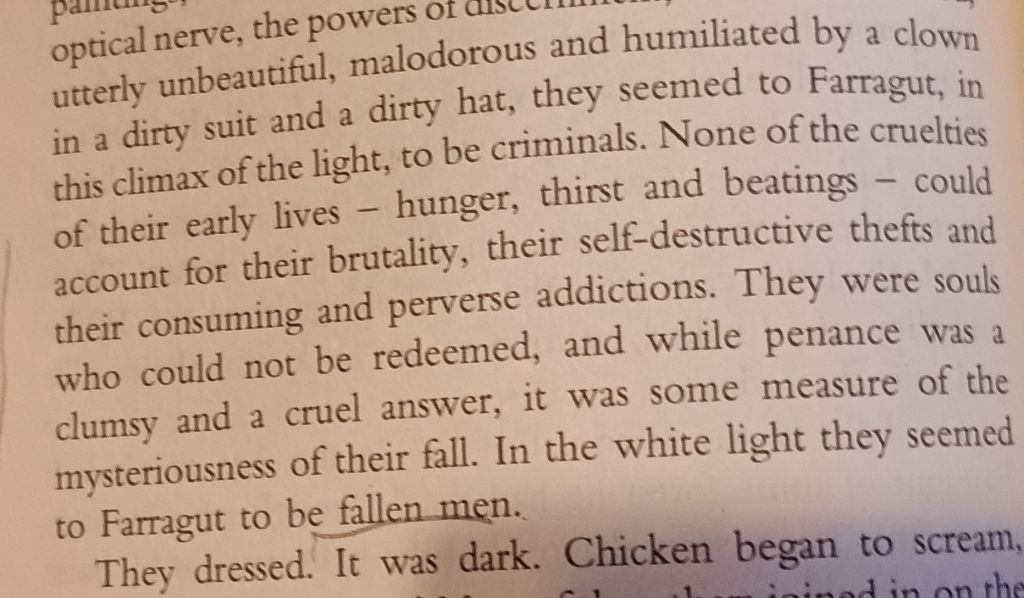

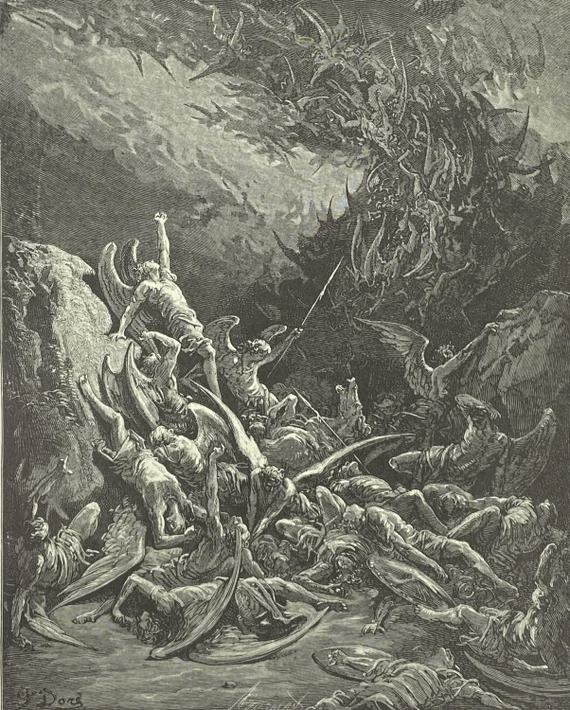

There is black and white in this space but no meaning, no writer of text and nothing but lies that govern a life so bounded by rules – from others or yourself as a group. Prisoners in a prison, that is like a dark forest , where the only communication is of lies are a version of Hell. It is a Hell like Sartre’s in Huis Clos where the prisoners contribute to the Hell made for them by another. It sings of Milton’s Hell. And maybe it is meant to. See this:

I shiver at phrases like ‘this climax of the light’. They lift the writing into the same empyrean as Milton and purposely. And like Paradise Lost, this work becomes sometimes a discourse on what it means to fall and keep falling. Dark and light, white and colours become confused and non-binary, for the reason any of us feel trapped is implicated in this work:

Why not read it in Milton himself, as Satan’s punishment and imprisonment is written there:

.... Him the Almighty Power

Hurld headlong flaming from th' Ethereal Skie

With hideous ruine and combustion down

To bottomless perdition, there to dwell

In Adamantine Chains and penal Fire,

Who durst defie th' Omnipotent to Arms.

Nine times the Space that measures Day and Night

To mortal men, he with his horrid crew

Lay vanquisht, rowling in the fiery Gulfe

Confounded though immortal: But his doom

Reserv'd him to more wrath; for now the thought

Both of lost happiness and lasting pain

Torments him; round he throws his baleful eyes

That witness'd huge affliction and dismay

Mixt with obdurate pride and stedfast hate:

At once as far as Angels kenn he views

The dismal Situation waste and wilde,

A Dungeon horrible, on all sides round

As one great Furnace flam'd, yet from those flames

No light, but rather darkness visible

Serv'd onely to discover sights of woe,

Regions of sorrow, doleful shades, where peace

And rest can never dwell, hope never comes

That comes to all; but torture without end

Still urges, and a fiery Deluge, fed

With ever-burning Sulphur unconsum'd:

Such place Eternal Justice had prepar'd

For those rebellious, here thir prison ordained

In utter darkness, and thir portion set

As far remov'd from God and light of Heav'n

As from the Center thrice to th' utmost Pole.

O how unlike the place from whence they fell!

There the companions of his fall, o'rewhelm'd

With Floods and Whirlwinds of tempestuous fire,

He soon discerns, and weltring by his side

One next himself in power, and next in crime,

Long after known in Palestine, and nam'd

Beelzebub. To whom th' Arch-Enemy,

And thence in Heav'n call'd Satan, with bold words

Breaking the horrid silence thus began.

If thou beest he; But O how fall'n! how chang'd

From him, who in the happy Realms of Light

Cloth'd with transcendent brightness didst out-shine

Myriads though bright:

‘Penal fire’ is telling. The prisoners in their ‘white light’ are ‘fallen men’ but the same urgencies apply to the writer elected to write about whether the apparently unredreemable can be redeemed and if so how to Cheever as to Milton. Falconer is a novel about forms of redemption, whether that be the man, Jody, Farragut lusted after and then longed for, freed without intention by a Cardinal but then raised up because he was not past giving the same Cardinal a good time or Farragut himself who takes on the role of a dead old man to be resurrected outside prison.

The novel ends with Farragut: ‘his head high, his back straight, and walked along nicely. Rejoice, he thought,rejoice’. [17] But that ending is very performative and the performative is suspect in this novel as here: ‘Farragut hurled himself onto his bunk and gave an impersonation of a man tortured by confinement, racked with stomach cramps and sexual backfires’. [18]

What I think does not pretend, although pretence may be our only redemption in the form of good fiction, is metaphor; rewriting metaphors from the past for our modern age. I used my favourite for my title in this blog. In this section Farragut is looking for the ‘way ahead of him’ and sees in it a ‘rectangle of pure white light’. This rectangle is a laundromat but it feels a little like Milton’s Hell:

It was a laundromat. Three men and two women of various ages and colors were waiting for their wash. The doors to most of the machines hung open like ovens. Opposite were the bull’s eye windows of drying machines, and in two he could see ‘clothes tossed and falling, always falling – falling heedlessly, it seemed, like falling souls or angels if their fall had ever been heedless. He stood at that window, this escaped and bloody convict, watching these strangers waiting for their clothes to be clean.[19]

But even in Hell people wait to be cleansed, if only through their clothes. Bing washed or smelling dirty is another powerful symbol in this novel. It just shows that old literature can be rewritten and its message. not revived but, renewed for our time. Hanif Kureishi says that Cheever said very little about his work in public but that in an edition of the Paris Review he does say ‘something significant’: Fiction is experimentation; when it ceases to be that, it ceases to be fiction. One never puts down a sentence without the feeling that it has never been put down before in such a way‘. [20]

In truth I will, I think, re-read these works and others I want to read too. As I read I know – for he is obviously a monumental writer – that I will sense that what I read ‘has never been put down before in such a way’. Please join me. Any feedback and /or chat in Cheever welcome. Or recommendations for next read!

With Love

Steve xxxxxxxxx

[1] John Cheever (2014: 181, first published 1977) Falconer London, Vintage, Random House.

[2] Olivia Laing'(2013: 7) book The Trip to Echo Springs: Why Writers Drink Edinburgh & London, Canongate.

[3] ibid: 3

[4] John Cheever (1990: 777f.) ‘The Swimmer’ in John Cheever Collected Stories London, Vintage, Random House, 776 – 788.

[5] ibid: 776

[6] ibid: 781

[7] ibid: 784

[8] Hanif Kureishi (1990: ix) ‘Introduction’ in John Cheever Collected Stories London, Vintage, Random House, vii-xi

[9] John Cheever (1990: 446) ‘The Country Husband’ in John Cheever Collected Stories London, Vintage, Random House, 420 – 446.

[10] Ralf Webb (2024: 214, 215 respectively) Strange Relations: Masculinity, Sexuality and Art in Mid-Century America, London, Hodder & Stoughton

[11] John Cheever (2014: 102, first published 1977) Falconer London, Vintage, Random House.

[12] Cheever cited in Ralf Webb, op.cit: 205f.

[13] photographic quotation from John Cheever (2014: 174f. first published 1977) Falconer London, Vintage, Random House.

[14] ibid: 151f.

[15] ibid: 144-146

[16] ibid: 147f.

[17] ibid: 184

[18] ibid: 136. See Chicken also on page 139.

[19] ibid: 180f.

[20] Hanif Kureishi, op. cit: x