It isn’t all that ‘crazy’ to experience a ‘time warp’ in a structure ‘shaped by time’. A novelist ‘obsessed by time as a structure’.[1] This is a blog on a beautiful, readable comedy of a transatlantic impossible meeting of ‘two sides of a single. A-side and B-side’.[2] Benjamin Myers (2024) Rare Singles London & Dublin, Bloomsbury Circus. BEWARE SPOILERS!

Some comedies are ‘problem plays’ it used to be insisted by the Shakespearian scholar F.S. Boas, who thought that the tone of comedy that is varied to include a remnant of the tragedies of mortality and the impossibility of wishful thinking (Measure for Measure is the canonical example) was the way a great artist registered the complex way of time passing was both sad and joyful, a pastime and a permanent loss of the unredeemable. When a novelist chooses for his model The Majestic Hotel in Scarborough. Yorkshire (a thinly disguised version of the real Grand Hotel) aa the venue for two peopld indergoing their own sort of life crisis, you can be sure if that novelist is Benjamin Myers that the ubiquity of the tensions of time as the source of pleasure and pain, comedy and tragedy will be present and perfect.

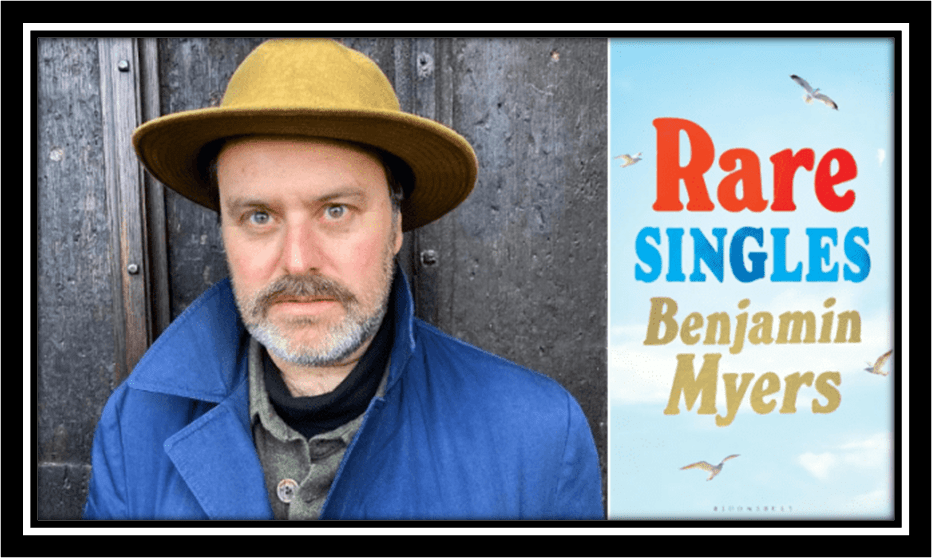

But I can’t help but contrast my feelings about the novel with some of the sterner reviews, especially that of the bugbear of bad critics of literature, Stuart Kelly, this time writing in The Spectator. Whilst others who do not read very deeply pass off their thin reading by talking about (did someone say ‘damning with faint praise’) the book’s charm, Kelly goes the whole hog by saying the novel is ‘deep-fried battered candyfloss, a slightly guilty and queasy pleasure. But a pleasure nonetheless’.[3] Clearly Kelly would have been in his element had the novel been set in Saltcoats and featured a ‘deep-fried Mars bar’.

The point is, I think, that no reader should commit to a reading of a novel unless they have at least tried to read what is in front of them, through some of its more problematic-to-stereotype passages.

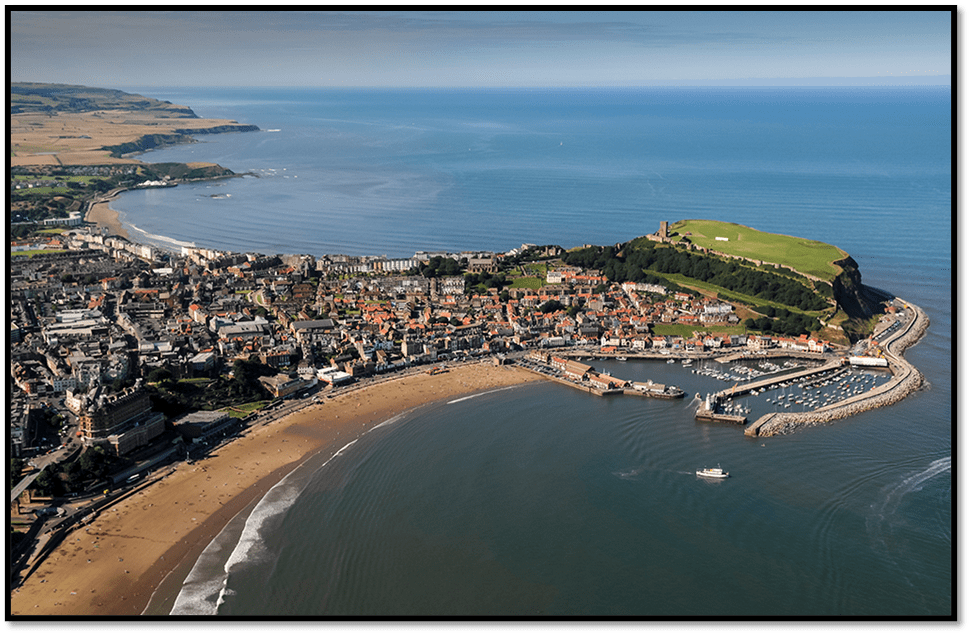

Scarborough, the setting for Benjamin Myers’s latest novel. [Getty Images]. North Bay is in the distance. South Bay Beach in the foreground from the Grand Hotel (Myers’ ‘Majestic’ – on the left) and the Castle on the peninsula that dissects the bays.

Yet most critics find this book a very different (and lesser) thing than Cuddy, Myers’ last novel, though few express the lessening effect on them as cattily as Kelly: ‘

Last year, the Proms had a ‘Northern Soul’ special concert; and Benjamin Myers won the Goldsmith’s Prize for Cuddy, his polyphonic novel about St Cuthbert’s afterlife. I do not think he will win the prize again this year for Rare Singles, his novel about Northern Soul.[4]

I think I agree if all this says is that Cuddy is a remarkable and towering work, but art works vary like that in any artist’s career: not all of their work will be as comprehensive or in the same register. Yet, in many ways this book takes up and sings in a different key themes about the human experience of time and mortality: similar themes to Cuddy, as Cuddy itself does with The Perfect Golden Circle, a point I tried to make in my blog on the former, that can be read at this link.

Some critics make a similar point but can’t help using authorial self-reference as a stick to beat the writer’s ego with, rather than allowing themselves the generous thought that authors modulate their tone in different works on similar themes because those themes are ones that require such treatment as they are returned to and replayed with difgerent nuance.. Thus Nick Duerden says, in an otherwise warm and full-of-praise review, that:

If occasionally (Myers) indulges himself by referencing his earlier work in the text – when a character gazes into the distance, he looks “out into the offing”, and when another is emotional, he “cries male tears”, a nod to the title of his 2021 short story collection – this is otherwise a wholly immersive story handled with great sensitivity.[5]

An even better critic, James Smart, makes reference to past works but this time in unmodified praise, saying that (though it could use Cuddy even more relevantly with regard to place – see my piece on how Myers made me see my home city Durham again at this link:

… like 2022’s The Perfect Golden Circle, it shares a deep sense of place with Myers’s previous works. Scarborough looms large, with its thriving seagulls, mostly downbeat inhabitants and “rugged, ragged” surroundings.[6]

The faded grandeur of the South Bay pleasure amenities (‘“rugged, ragged” surroundings’) In Scarborough (Photo: Getty)

I may be wrong but I don’t get the sense that James Smart actually visits Scarborough himself or would indeed do so to check the way Myer’s descriptions match it. Neither does he seem to realises how offensive it is to suggest that as a novelist Myers focuses on the town’s ‘mostly downbeat inhabitants’. Smart means of course the husband and son of Dinah, but there is no suggestion in Myers that these stereotypical substance-fuelled ‘down-and-outs’ typify East Yorkshire.

Likewise, I think Duerden, doesn’t quite get that Myers object is to break down stereotypes of the Northern ‘soul’, and not just in terms of a musical genre. Shabana’s role, and you hear mostly her Yorkshire accent, is to break down stereotypes of class, race and migrant status, although Duerden does state good evidence for such a view.

In the dilapidated hotel he has been put up in, he bonds with immigrant cleaner Shabana, who surprises him with her intellect. “Just because I carry a mop does not make me a cleaner for the rest of my life,” she tells him, “any more than you having legs makes you a table.”[7]

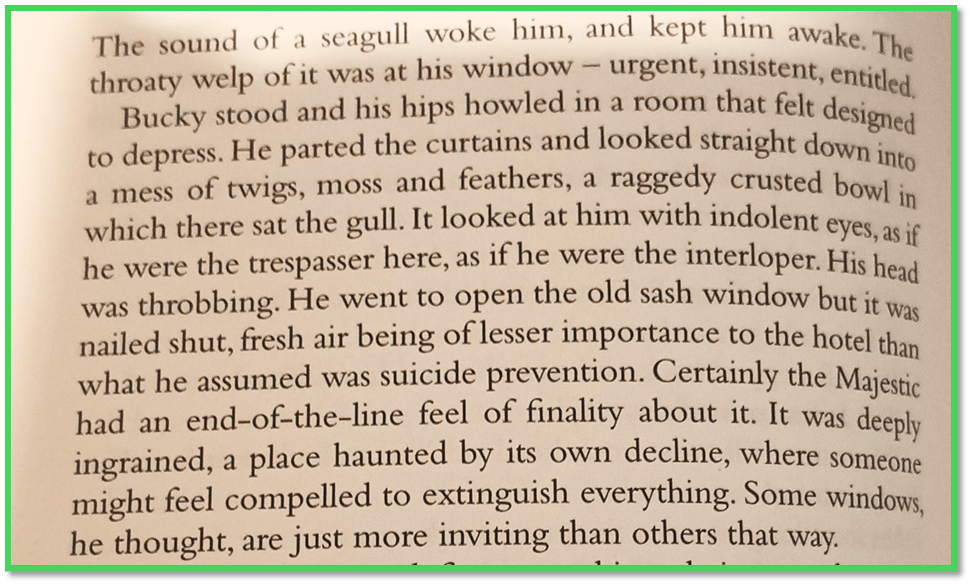

Most of all I guess (and again I may be wrong) that neither Smart nor Duerden would try out that ‘dilapidated hotel’ mentioned in the passage above, The Majestic Hotel. Myers has clearly tried the Grand Hotel, on which it is based, out by staying there, so accurate are his descriptions even down to the perpetually broken-down lifts, the nailed-shut wooden window-frames and the priority of residence given to seagulls of, at least, what this Hotel was like when I and my now dead parents stayed there. It is there we meet ‘downbeat inhabitants’ but this is meant to signify its reputation for cheap package deals for working class inland urban Yorkshire families, the cheap booze and torrid Northern working-men’s club entertainments. But it is precisely the passages that describe The Majestic Hotel (in the eyes of Shabana at least who cleans the vomit up in its huge entertainment arenas) where Myers revisits his primal themes (indeed basic human-animal themes) of survival across swathes of time and space). In my blog on Cuddy, I refer to the symbolic use of the built environment of the whole of Durham to capture themes of human enclosure and liberation as matters central to social and imagined spaces. Here is an example:

Seen from the [Durham] Cathedral tower, [Durham] prison is an ‘an enclosed space’ contrasted with the ‘total freedom’ of feeling a chilling winter wind at this built altitude.[2] This contrast of prison and cathedral is a false one however when seen from the perspective of the deliberately neglected dying Scottish teenage prisoners of Crowell’s Scottish wars (a fact of the once decommissioned Cathedral’s history that was recently unearthed) and is brought to life again in a brief play within the novel. In the play a voiceover (V/O) narrator is the Cathedral itself: ‘Cathedral (Voiceover): Thirty hundred bodies barred in; all of them Scots, my exits barricaded. … call me a coffin, a mausoleum for the many’.[3]

In this novel, The Majestic plays a similar role, not as merely an iconic old ‘dilapidated hotel’ , but as symbol of how space and time can be conceptualised and how the myths implicit in this conceptualisation can be queried.

Even the poor collage I have assembled will give you some sense of the accuracy of the exterior descriptions in capturing the Scarborough Grand Hotel if not quite of its sad interior as it was at least at the time of the novel’s setting, where the carpets are sticky with the alcohol you smell in its vaulted halls of empty air. Likewise the emotion of these books is, as in The Gallows Pole, such that it refuses to play the class games of the great tradition of the English novel (less the Scots novel if you exclude Stuart Kelly’s versions thereof) and thus is called by academically trained critics as ‘sentimentality’: ‘Sentimentality is not a bad thing per se, but it is a difficult genre to do well, and Myers doesn’t do it half badly’, says Kelly in a prose that like much he writes never avoids the nose-in-the-air sneer of a lover, without that author’s beautiful artistic vision and genuine empathy, of Henry James.[8] Thus, even though Kelly thinks he has captured the joke in the novel’s title by witing of Bucky Bronco as ‘an elderly American widower wracked by pain, whose musical career comprised two singles, one barely released and both largely forgotten’ misses the fact that ‘singles’ is an obviously ambiguous word, referring to persons who are humanly ‘single’ until they connect to others, after all Dinah says of herself that she ‘might as well be single’.[9] And Myers even employs unadvertised metaphysical wit (in the seventeenth-century sense applied to Donne and Marvell).

There is no closure in the relationship of Dinah and Bucky by the end of the novel, but there is a metaphysical wit in showing the tensions of a desire for closure (a nice ending) and the fact that such endings are rare in Myers’s use of a witty conceit, as good and contemporary as Donne’s use of compasses to describe his lovers, although Myers uses no teenage reference (as it is in our time and place) like Donne to ‘stiff’, erection or ‘come’ ambiguities.

If they be two, they are two so As stiff twin compasses are two; Thy soul, the fixed foot, makes no show To move, but doth, if the other do. And though it in the center sit, Yet when the other far doth roam, It leans and hearkens after it, And grows erect, as that comes home.[10]

Myers instead has his character, Dinah, refer to Bucky and her as potential lovers as ‘two sides of a single. A-side and B-side’.[11] The point of an A and B side on one record is that though they subsist in proximity to each other they can never just become assimilated, they are immutably separate things. Myer’s Majestic Hotel is similarly a kind of conceit of the novel’s themes, and hence I use it in my title to refer to larger intellectual, emotional and metaphysical (in the philosopher’s sense in querying concepts of time and space) themes of the novel. Shabans says of the hotel she cleans but which job does not define her, any more than her current class, ‘race’ (she is Afghan) or immigration status:

… it’s like stepping back into history. … I’m telling you, this place is crazy; it is a time warp, which is funny because the entire hotel is shaped by time. It is defined by the calendar. / … it seems the architect was obsessed by time as a structure’.[12]

She goes on to describe how the 4 towers symbolise the season, the 12 floors the months, the 52 chimneys the weeks, the 365 rooms the days in the Gregorian calendar year. Bucky equates the ‘numerical impulse’ implied to the discussion of numerology that flits through the novel too, variously articulating the themes not only of counted time, distance, accumulations (of amounts of money for instance) and repetitions (the number of ‘hits’ on a modern digitised recording of music) but also of mystical projections of the themes of divinatory meaning (Bucky is in Room 333 which Dinah sees as related to 666, the mark of the Beast at the Apocalypse). These are ‘witty’ games that emphasise the concern with space and time concepts – even those of the cyclical and/or sequential measurement of time are implicit in Bucky’s signature song from his past carer : Until the Wheels Fall Off, for time cycles in numbers until it meets with a fall and then, for some one at least, it ends unless we start counting it again in new circumstances. Bucky’s songs are all about time and human constructions of it, but then are so many songs, like Rufus Redwood’s Midnight is Just a Passing Moment (as it is referred to in the novel, though probably based on the song duet with Chaka Khan At Midnight (My Love Will Lift You Up). It is even more obvious in Bucky’s putative All the Way Through to the Morning.[13]

I ought to stop flogging the dead tractor (never would flog a horse) but Kelly even misses this point in magnifying his own ‘research’ for his critique on the novel:

Myers makes a wise call in not describing the actual songs and leaving them to the imagination, although, with my suddenly acquired expertise, I’d have thought there would be nods to the ‘three before eight’, for example.[14]

What Kelly means in the last phrase I barely care but the point is that the novelist gives us enough of his ‘soul artist’s’ words to capture the necessary theme, the response to time and space as it is manipulated through human emotion and connection to others or ‘another’. Indeed the novel even quotes lyrics in ways this critic thinks he doesn’t but does so in contexts where characters dialogue, as we all do all the time, on the effect of how time seems to move in our respective and differently paced contributions to conversation:

Here Shabana started singing a melody that was familiar to Bucky. It was the main melodic hook for his unreleased second single ‘All the Way Through to the Morning’ , but it followed a slightly different cadence. …

‘Wait a minute,’ said Bucky, taking a step back. ‘Hold up, just a minute. First of all, how in the hell do you know that song? No one apart from a few soul fans know of it. Also, it’s fifty-some years old and was never even released anyway. And, secondly, you’re a rapper?…

‘Well, firstly, only about a million kids know that line: You and me, we’re gonna be alright, because tonight we’re going to dance all the way through to the morning. And, secondly, hell yes, I’m a rapper’.[15]

It is not just that musical terms, like cadence for instance, always refer to the management of time in musical expression and rhythm, as a former music journalist like Myers knows so well, but that the Language here constantly refers to the count and feel of time, including beginnings and endings and the way that durations are constantly projected into longer phrases – for instance how does what happens through one night relate to what is likely to be the future we look forward to in time, but in circumstances of shared emotion it often does. Even more so do those references to time and the feel of time (so often a vacancy or ‘hole’) emerge here:

He startled himself with the snatches and snippets that he shouted out – ‘my soul has a hole as deep as history’, … – before he realised they were all fragments of his own songs, lyrics he had not uttered, never mind sung, since the last century.[16]

Duration, continuity, disruption and the sense of presence and absence in history all proceed from these ideas and feelings. How can Kelly get away with hearing himself say Myers is ‘not describing the actual songs and leaving them to the imagination’, unless he skip reads where it matters, as in those pieces I cite above. As I read every paragraph was replete with ambiguous and contradictory reflections on the feel of time and space in which one is present or absent, proximate or remote. Try this but read deep if you want to know why writers sometimes touch genius. It describes Bucky singing, at last, Until The Wheels Fall Off, whilst recalling its original recording by Sweet Chariot (itself a reference to a metaphor (though it is the name clearly of a music recording company) for time with complex references in Louis Armstrong’s version of the song to the call through time that brings freedom or death and may not distinguish either).

Adjectives, verbs and participles all reference time or sensations of pace in sound and vary the time perspectives at play – from the momentary expectations of something to beginning to the longue duréeof a memory ‘delivered from a past age’. The sense of the episodic and chronically regular play against each other, whilst the over-riding myth of Rip Van Winkle records a well-known absence from history. Idiom like ‘bounce him back’ chime with other time-based idioms we see elsewhere, like ‘step back’ that confound temporal with spatial concepts. This is writing whose triggers are concealed but will have an effect on reading.

And that is more so with other emblems of things in a ‘time warp’, not unlike The Majestic Hotel, which thought it had time covered by its own static assemblage of numerological motifs so that it decays the more obviously. Consider, for instance, Bucky’s reference to a mythic England that never existed, an ‘ancient kingdom’ or ‘land’ until Bucky remembers all lands are ‘ancient’, except not always in human configurations of them.[17] Travelling through villages in Yorkshire on arrival Bucky feels that: ‘Time peeled back its layers …’.[18] In a Scarborough curio shop feels the enormity of time and comparisons of pasts. That of Jesus compared to a ‘little louse that crawled the earth 4,500,000 centuries ago’, as he traps the trilobite in his palm, trapping it as it is trapped in non-progression: it ‘had had a heart. It still did now, calcified in stone and pressed between the pages of a story called time’.[19] The tenses of the verbs in this passage and around it do an immense amount of additional work as they are read, and perhaps not even consciously noticed. There are also no end of means of measuring time in numbers in this novel – many clocks and watches (some like those of Dali melt), as well as travelling schedules for transport, waiting lists for hospital for medical procedures such as Bucky’s arthritis.[20]

There are also different ways of USING time. People measure the business and ‘busy-ness’ (not always the same thing) by the sense of having time or no time to do things.[21] Others spend or consume it in being one of the ‘hardcore mainstays‘ in a pub or church or the Scarborough Spring Gardens show venue for instance, compared to those who merely ‘while away a few stray hours’. Some pub seats show time imprinted on them; time experienced as ‘routine, regularity, repetition (a Freudian alliteration to my mind like that of mourning in the great man’s mind).[22]

Even the body has a ‘clock’ that does not measure the same time as a watch, especially in the throes of addiction, or in the imagination of unknown ghosts.[23] The older life measures time differently from younger ones, whilst some do not move in it at all, but ‘stagnate’ like Dinah’s twenty-some year-old son. Time perspectives get mixed up so much sometimes, as most plainly here, where the future spoken of is the present in which the words are spoken: “We’re living in crazy times, Dina. No one ever told us the future would be this strange’. [24] The verb’s tense here, again, does a lot of work. Time is implicit in the work of journalism as the term ‘old news’ often reminds us, which is what Bucky thinks he is: ‘no record company, no website, no email address. Nor are you registered for publishing royalties’, and lot of consequences (and money) hang on this thought.[25] And sometimes time needs to be re-experienced as repetition in order to be ‘remembered, repeated and worked through’ to come to term with highly significant losses, like that of Bucky’s wife Maybellene and brother, Sess (Cecil),[26]

The burden of all this is that this novel, like Cuddy measures history’ against the felt sense of passing time in individuals and as the lever of good and bad relationships, in which stagnation and a sense of moving on matter. It applies to some of the discourse of aging and Death in the novel of course, as well as the meaning of ‘pain’. But it also talks about the function of memory and forgetting, repression and the return of the repressed. Sometimes the correct extended metaphor for the interplay of regression and projection and returns to the present is the contrast of land (a static hell) and sea (a fluid but fearsome and lonely means of escaping being trapped in time – why Dinah is a swimmer and why being with Russell feels like being anchored)[27] – most notably in this passage (I keep wondering if Kelly finds it ‘sentimental’), which I think (to Myers) is an image of a Sartrean Hell, like that in Huis Clos.

Hell.

And the sea itself was a shifting abyss, its charcoal water hot through with fins of silver light in a state of constant rearrangement and reconfiguration.

In that moment it felt like the loneliest place on earth, the sea, … for it suggested an existential desolation that was expansive.[28]

The word ‘existential’ is telling. Going in the sea involves immersing yourself in conscious choice rather following time set out and regulated by calendars, clocks and decaying ideas like the Hotel Majestic, where only the seagulls get its meaning. For Bucky coming to Britain means a kickback against a state thoroughly privatised into decay and a lack of empathy into what that state sees as ‘socialism’, though it means little more than a socialised health service.[29] To be stuck in the past, to be not living though alive as Bucky and Dinah are both has its own terrible image that of being neither alive nor dead but a remnant of waste, of being ‘excremental’.[30]

The redemptive image of the book of circus is the circle of time that returns as well as gets lost in a constant cycle or spiral. Wheels have that function as does the ‘circus’, which is a reminder three times, at least in the novel of the repeated thing you do not yet understand but must, for circles are ‘coming’ not ‘going’, they have a possible future like Dinah and Bucky at the novels end:

The same truck that Bucky had seen circulating that morning – that promised – threatened almost – that The Circus Is coming to Town! He couldn’t see who was driving it, and so its appearance felt spectral. It glided by, as if he were the only person to see it.[31]

The alternative to this continual recycling (‘circulating’) threat and promise of is a wasted ending – suicide – and this is a haunting presence of this novel, associated with The Majestic Hotel, and the ‘seagulls that threaten to become its only truly living inhabitants, as a sign of their ancient link to the past: ‘neat black claws, pre-historic looking. They spoke of attack, death, evisceration. Ancient times’.[32]

A Scarborough seagull eviscerates a stolen potato chip.

Coming to the decay of The majestic for the first time, Bucky realises that, were its windows not nailed down, it speaks of the finality of suicide in chorus with the urgent, insistent, entitled’ gull on his window’s external ledge:

This is good writing, though no doubt ‘sentimental’ to a person of Stuart Kelly’s refinement, because it projects the depression within Bucky in ways that feel to him he is introjecting – Melanie Klein called this ‘projective identification’. If the Majestic is no longer majestic except in some obviously parodic way, it not only bruits its ‘decline’ over time, and elsewhere ‘decay’, like excrement, but also its invitation to suicide , because some ‘windows, are just more inviting than others that way’. Compare this gentle allegory of despair to the similar situation of the ‘Redcrosse Knight’ in Book 1, Canto 9 of The Faerie Queene by Edmund Spenser wherein the allegorical figure of Despair is confronted: is there not an equivalence across time.

Stanza XXXV That darkesome cave they enter, where they find That cursed man, low sitting on the ground, Musing full sadly in his sullein mind; 310 His griesie lockes, long growen, and unbound, Disordred hong about his shoulders round, And hid his face; through which his hollow eyne Lookt deadly dull, and stared as astound; His raw-bone cheekes, through penurie and pine, 315 Were shronke into his jawes, as° he did never dine. ……… Stanza XLIV Then do no further goe, no further stray, But here lie downe, and to thy rest betake, 390 Th' ill to prevent, that life ensewen may. For what hath life, that may it loved make, And gives not rather cause it to forsake? Feare, sicknesse, age, losse, labour, sorrow, strife, Paine, hunger, cold, that makes the hart to quake; 395 And ever fickle fortune rageth rife, All which, and thousands mo do make a loathsome life.

‘Sentimental old Spenser’, sighs the semi-education of Stuart Kelly. I think we need to begin to think about reading again and divorce from the need in journalistic critics to find fault, for they have read the novels they declare sentence upon too few times, often not very closely to generalise about their value. I sometimes think that modern teaching encourages evaluation far too earlier before comprehension, deeper understanding and appreciation are there. So this is not really moaning about Stuart Kelly. He is one of many, but being fairer to writing, lest we fail to see just how good it is, despite its surface qualities. But let’s be fair. Kelly does find good composition – actually the arrangement of events in a time framework, and words. Sentences, paragraphs and chapters into atemporal rhythm, as here: ‘The third act is well-paced between flashbacks and the closure; and the whole has a pleasantly distinctive humour – ….’.[33] but the final phrase here diminishes the achievement it pretends to praise. The critic should have seen that the play with narrative method was part of the treatment of a Benjamin Myers theme (one he is making his own) and just appreciated it – and bowed to grateful READERS not exercise critical muscle.

Do read this BEAUTIFUL book

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Benjamin Myers (2024: 148f.) Rare Singles London & Dublin, Bloomsbury Circus

[2] Ibid: 206

[3] Stuart Kelly (2024) ‘An unlikely comeback: Rare Singles, by Benjamin Myers, reviewed’ in The Spectator (10 August 2024). Available at: https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/an-unlikely-comeback-rare-singles-by-benjamin-myers-reviewed/

[4] Kelly, op.cit.

[5] Nick Duerden (2024) ‘Rare Singles by Benjamin Myers is a novel I didn’t want to end’ in The i newspaper (July 27, 2024 6:00 am (Updated 6:01 am)) Available at: https://inews.co.uk/culture/books/rare-singles-benjamin-myers-review-novel-didnt-want-end-3179551

[6] James Smart (2024: 52) ‘Heart and soul’ in The Guardian Saturday Supplement (Sat. 03/08/24), 52f.

[7] Duerden, op.cit.

[8] Kelly op.cit.

[9] Myers 2024 op.cit: 86

[10] John Donne A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning.. For the complete poem see: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44131/a-valediction-forbidding-mourning

[11] Myers 2024 op.cit: 206

[12] ibid 148f.

[13] Ibid: 122f.

[14] Kelly, op.cit.

[15] Myers 2024 op.cit: 150.

[16] Ibid: 157

[17] Ibid: 4 & 134

[18] Ibid: 18

[19] Ibid: 129

[20] Ibid: 1 & 3 respectively

[21] For instance, ibid: 29, 124

[22] Ibid: 124

[23] Ibid: 70. A powerful passage. See also ibid: 92

[24] Ibid: 86

[25] Ibid: 94

[26] See ibid: 178

[27] Ibid: 60

[28] Ibid: 73

[29] Ibid: 4

[30] Ibid: 107, the italics are those of Myers

[31] Ibid: 47f. But see also, 27 & 131.

[32] Ibid: 80

[33] Kelly, op.cit.

One thought on “It isn’t all that ‘crazy’ to experience a ‘time warp’ in a structure ‘shaped by time’. A novelist ‘obsessed by time as a structure’. Benjamin Myers (2024) ‘Rare Singles’.”