‘The edge is where I’m from. It’s my home’.[1] From an autobiographical account of recovery containing encounters with representations of worlds considered as both real and only liminally so to the making of performance-oriented art forms. Preparing to see a performed adaptation of Amy Liptrot’s ‘The Outrun’ by reading the book.

Sometimes a memoir’s significance hangs on the ideas associated in wide networks with a single term and, in a sense, this is true of Amy Liptrot’s The Outrun, for the appropriate term is its title, a title that requires from the start an explanation, at least for the form of the term that is a noun. ‘Outrun’ as a verb has some sense – suggesting the act of running beyond the capabilities of someone else to catch one up. But the term here is a noun, and although we are told it can have generalised signification, at least in the Orkney Isles, where much of the memoir is set, it is the basis for reflection on the past and the present as it outruns that past and turns towards the future. But before even examining this, I want to stress that the potential meanings of ‘a’ or ‘the’ outrun, for we are often dealing with a specific instance of an outrun than outruns in generality its basic signification and often generates other terms or idioms.

The key one I will want to talk about is the idiomatic phrase ‘on the edge’, although, maybe, the thing about all ‘edges’ between things, whether physical things, states of being or borders of other kinds, edges often have a relationship to liminality, where events on the edge, or ‘cusp’ or ‘threshold’ to use other possible terms, become indeterminate and unfixed in definition, their own edges fuzzy.

This is deliberately so in Liptrot’s writing, which in itself often takes on the characteristics of differing generic types – including memoir, recovery narrative, reflective accounts of the real or imagined situation being faced such as those in nostos (homecoming) narratives, aggregation of global, folk or personal myths or retail of knowledge from domains considered ‘factual’. The latter include the study of eco-systems, eco-geographies, the interactions of climate and both physical systems and human manipulations thereof, addiction psychology or neuroscience, animal biology, sociology or urban sociology. Finding the dividing edge between such subjects is not made easy. In my view, anyway, it never should be for specialisation distorts truths and teplaces them with narrow accuracy.

The context for writing about the book is that on Thursday evening upcoming [tonight], I will see the Lyceum Theatre’s theatrical version of the book, using audio-visual additional material as well as the usual repertoire of theatrical illusion creation to tell the story in its own way. Imagining this, with the help of reviews already published, will happen later. Moreover, it will refer to the fact that in September 2024, the film of the same book will be released – a film already shown at this year’s Edinburgh Film Festival. But that for later. The thing for me is to imagine how a book of this kind lends itself to theatre and film, each in their different means and conventions. As a starting point, I thought it best to detail what I saw as the key characteristics of the book’ They are, and are dealt with in this order:

- FASCINATION WITH THE EDGE OF THINGS;

- THE NATURE OF ADDICTION NARRATIVES OR PERSONAL ACCOUNTS OF RECOVERY;

- THE PHYSICS AND PSYCHOLOGY OF DURABILITY OR FRAGILITY AS CONCEPTS (INCLUDING CONSERVATION & ENTROPY) & THE EPISTEMOLOGY OF REAL AND / OR IMAGINED ‘WORLDS’.

That these domains deal with abstractions is inevitable, for the issue with this book is precisely that it evades simple categorisation or undermines them. This is not new to literature. Perhaps the most persistent life-long study of the edge of real and imagined worlds, for instance, was that by Robert Browning, whose Bishop Blougram says to the journalist who interviews him, Gigadibs, and of the cognitive-emotional and sensual world he proceeds from:

You see one lad o'erstride a chimney-stack;

Him you must watch—he's sure to fall, yet stands!

Our interest's on the dangerous edge of things.

The honest thief, the tender murderer,

The superstitious atheist, demirep

That loves and saves her soul in new French books—

We watch while these in equilibrium keep

The giddy line midway: one step aside,

They're classed and done with.[2]

Of course, I do not say that Liptrot’s purpose is to ‘avoid being ‘classed and done with’. Her aim is to illustrate that this is the truth of the set of worlds in which we all live, a truth we often only glimpse when we accidentally, purposely, or by dint of some predetermination over which we have no or limited control, live in a manner that cannot be explicable except in terms of being, precisely, ‘on the dangerous edge of things’, where a step or fall either way might ensure ‘we’re done with’, explained and understood and trapped in the same reductive explanation and understanding. So, to start:

FASCINATION WITH THE EDGE OF THINGS

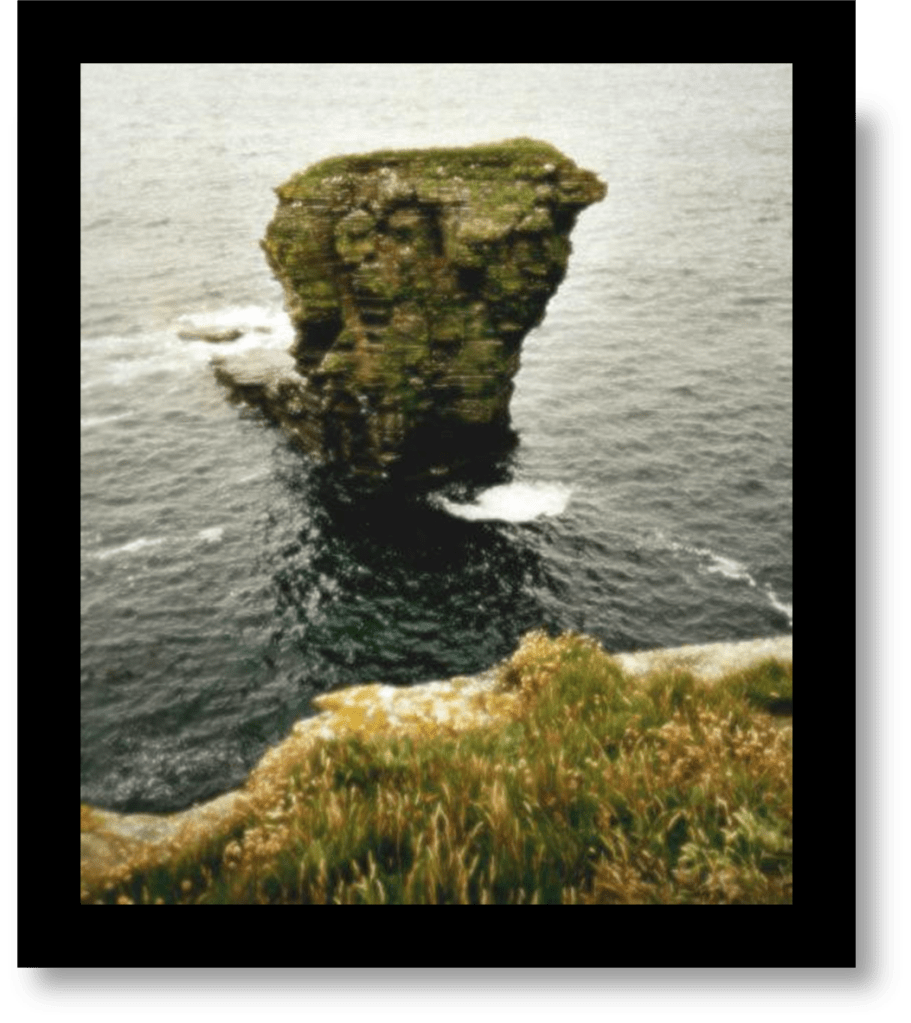

An outrun, even the one that was at the margin of her father’s farm, is a place where strange things happen, like the stranding of a large fishing boat on an outcrop of the cliff seen most clearly from the top at the cliff’s edge. ‘Something had happened at the Outrun’ is a sentence the starts Chapter 7 on the occurrences of coastal sea wrecks.[3] It doesn’t take long into the chapter for Liptrot to make analogy with this wreck to her own situation: ‘Almost twenty years later, like the boat, I was in a precarious position’.[4]

The confluence in this example of an outrun to a farm (uncertainly in the possession of the farmer that is her father), a sea coastal margin, a cliff and its edge is typical of the book as is the application of analogy to vulnerable lives, not least that of the memoirist. One of the clearest passages shows how these analogies are shaped from multiple associations between the circumstances of a life and its interior as well as external events:

I was born into dramatic scenes, lived in the landscape of shipwrecks and howling storms, with animal birth and death, religious visions, on the edge of chaos, with the possibility of something exciting happening at the same time as the threat of something going wrong. A part of me thinks that these widely swinging fluctuations are, if not normal, at least desirable, and I grew to expect and even seek the edge. The alternative, of balance, seems pale and limited. I seek sensation and want to be more alive.[5]

The literal edge of a cliff may be attractive, but it isn’t because, even to the boy in Bishop Blougram on a London rooftop, we love ‘balance’. At some point, the excitement needs to experience at least the imagination of a fall and the wreckage of hopes and sometimes body that would ensue. That is the excitement gained from the dangerous edge of a cliff, which needs to take seriously the potential fall into the chaos you see from its edge.

This analogy is so powerful in the novel that it fuels even the odd hidden metaphor of falling or diving. Much earlier, Amy talks about, as a child, loving to throw her ‘body from high rafters onto hay or wool bags’ on her father’s farm. ‘Later’, she continues, ‘I plunged myself into parties – alcohol, drugs, relationships, sex – wanting to taste the extremes, … and raging against those who warned me away from the edge’.[6] Other language for these psychological and physical, as well as imaginatively experienced states – even in imaginatively thin dead metaphors like ‘plunge’, are those of ‘heightened states’ (actually still evoking a cliff edge though via another dead metaphor) or the quality of being ‘impulsive’.[7]

Sometimes, the metaphors are similes, evoking how a state of mind resembles the physical circumstances of the Outrun and the unintelligibility of some of the liminal experiences met there. For instance, finding a starfish on the ‘top of a cliff’ may evoke explanation, but the explanation is not necessarily sufficient for the queerness also evoked. She describes how her mind works in walking as ‘free’ precisely because the body is ‘occupied’ in a way that liberated mind. And then Amy says: ‘Like the Outrun, there is more here than at first it may seem. I find a starfish at the top of the cliff; it must have been dropped by a bird’.[8]

The search for explanations yields supposed solutions but the solutions don’t dissolve the strangness of a sea creature at the wrong side of the border of its life-defining and enabling boundaries: high, not deep, on land, not sea, and so on. The strangeness enters into imaginary terms when the narrative pursues selkies, or stories of selkies, and not just in literary sources like Orkney poet, a favourite of mine too, George Mackay Brown. But of ‘selkies’, let’s talk later.

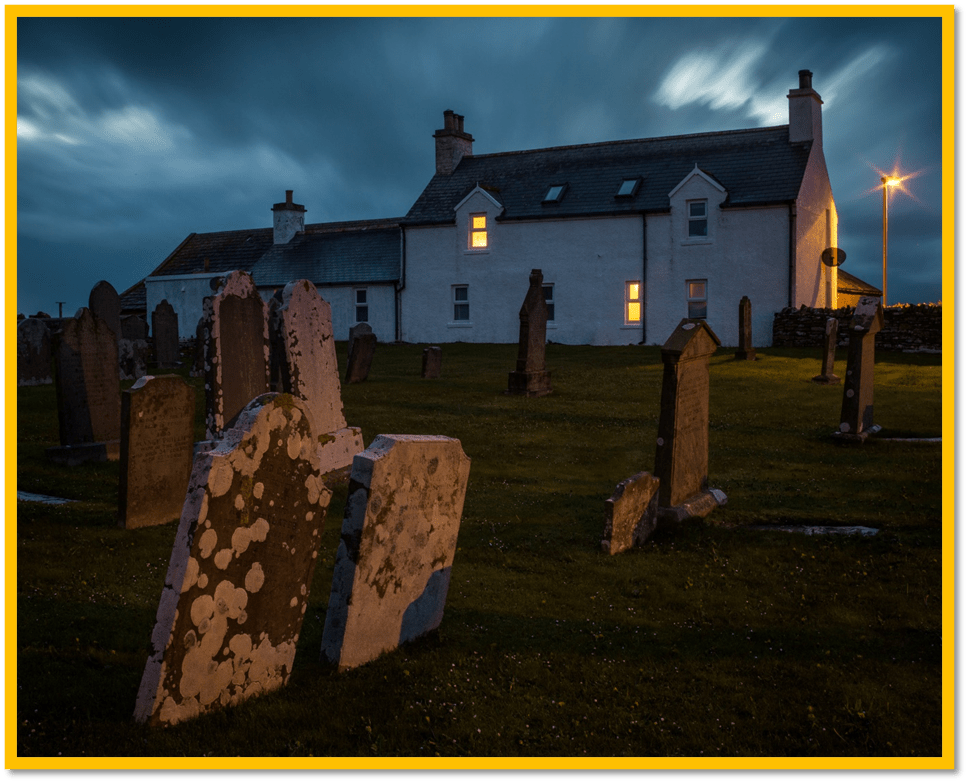

An ’outrun’ is claimed as an Orkney word and in Amy’s father’s farm it has the name, she calls ‘prosaic’ like all the field names (‘front field’ for instance), except that she names ‘Outrun’ alone with a capital ‘O’ .It is the name of the ‘largest of the fields’: ‘a stretch of coastland at the top of the farm where the grass is always short, pummelled by wind and sea-spray year-round’. The name derives, she tells us, from the divisions of agricultural ground recorded in historical plans wherein the ‘in-bye’ is ‘arable land, close to the farm’ stead, and the ‘out-bye’, or ‘outrun’, is ‘uncultivated rough grazing, further away, often in the hillsides’.

It is a name that ‘others’ the land and was once communal she suggests rather than privately owned, but is also ‘only semi-tamed, where domestic and wild animals coexist and humans don’t often visit so spirit people are free to roam’.[9] It is this quality of liminal identity on the wide boundary of the binaries it ought to serve to separate like land and sea, tame/domestic and wild, flesh and spirits which makes the outrun ideal for the memoir to see it as analogous to places, like London, where the untamed, and ‘spirits’ of a different set of substances have free play. Some get queer bodies in tje outrun – but again, that takes us to ‘selkies’, and that’s later. It is a place where appetites are tested and sometimes get out of control, on the outrun of addiction, of which more later.

But as in the Browning cited above, we are speaking of ‘the dangerous edge of things’. Living on the edge is dangerous even on a farm for the vulnerable and unhabituated. In her childhood, the danger is physical in the form of a cliff edge that bounded sea and outrun. She remembers : ‘We had a dog once that went over. The collie pup set off chasing rabbits in a gale, did not notice the drop, and was never seen again’.[10]

Even a ‘neighbour’s tractor’ is sent ‘driverless, … with unstoppable force, to plunge ‘over the edge of the field’.[11] One can become habituated to the edge like her father’s mature sheep and confident that because ‘geographical knowledge and foot-sureness,’ would be ‘bred into the bloodline’ there was no need to create fences on the cliff-edge, though in the early days she remembered that Dad ‘rescued ewes that got stuck on edges’ in the cliff-wall.

I think Amy therefore uses her absorption in the image of the Orkney Islands in all their variety to examine the realities of need (intellectual, emotional, sensual, or even spiritual if you like) for a sense of a Higher Power, a combination of the human body (individual and social), natural process and imaginative power that transcends it, at least in imagination and might, at its best equate with art. And nature in the Orkneys has all the lessons, especially if we take control and, simultaneously, let go of our need to dominate nature, giving it back in part to supernature, even selkies. For instance in her work on the conservation of threatened species this occurs a lot. She is aware of those in danger of extinction right from the beginning of the novel before we know that she has become dedicated to natural and environmental conservation, such as in her knowledge of ‘the great endangered bumble bee’ living in the ‘red clover’ on a cliff-face that is the home of Arctic terns near the beginning of the novel.

We should pause here to recall the fate of Gabriel Oak’s sheep in Far From The Madding Crowd, chased over a cliff-edge by a young collie, that destroys his living and puts him in the outrun, a potential wage-slave not a gentleman farmer, and the dog which had, by a farmer’s standard, to be shot, as was the fate of a canine outrunner run to the wild in its unregulated needs.

The cliffs are not the only edges and boundaries of the Outrun in Orkney physical and social geography. Amy knows the ‘broken-down and overgrown boundary dyke’ on her father’s land dated to Neolithic times that may contain a stone dropped on its way to form the mysterious Ring of Brodgar from a nearby quarry to that Outrun. The thing about the Outrun is that, though it may play dead in winter, it isn’t; it is instinct instead with the life that is the binary opposite of its current mask of dying. As Amy says, ‘the Outrun seems barren, but I know its secrets’.

And well that she does for it might have been better, she thinks, had she applied the analogy of this coastal phenomenon subsisting between two realities, one in its depth quite alien to us (unless we are a selkie), the other more hollow than it sometimes looks, as she reflects whilst watching seabirds nesting on a sea-stack, the Stack of Roo, whilst sitting right on a cliff-edge:

Hardy sea pinks grew at the cliff edge and I used to see white tails disappearing down rabbit holes where puffins nested. The ledge felt solid but, looking from another direction, you could see that it was overhanging. Unsettled in London, I felt as if I was dangerously suspended high above crashing waves.[12]

My experience and that of others in addiction is that addicts cling to the belief that the ground is ‘solid’ beneath them, rarely venturing to find another way of looking at it ‘from another direction’ or listening to the perspectives of those who see danger. Some, of course, crash into the waves, and my heart breaks to think of it in one case and makes me frame the next picture in black.

But liminal experience is sometimes that which we do not wish for but are born with, or acquire from a confluence of determinationsn not all in our control. That this has happened ought not to make us ashamed if it has occurred to us, and I think Amy learns to accept her father’s mental health states and his attempts like her for temporal recovery, even if with lapses into safer addiction types or controllable symptoms. Her Dad’s highs in bipolar illness are not unlike the cliff-fugues of the novel or of Amy’s own longing. She knows her Dad first discovered that high edges can be the friend, as well as the enemy, for it is a place as the memoir knows of contemplative suicide, of unregulated and probably unregulatable mental stress. Indeed, he teaches her this learning in facing fears and dangers directly and not hiding them under shallower risk assessments. The Outrun is, after all, a secret and private place:

The Outrun is tucked away behind a low hill and beside the coast, and in the right spot you can’t see any houses or be seen from the road Dad told me that when he was high, in a manic phase, he had slept out here. At the end of the day, crouched away from the wind , …, rolling a cigarette and eyeing the livestock, I have become my father.[13]

Only those in stress truly understand its meaning for others, too, which people say in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and mental health support groups. That includes its complex fears and drives. Hence what Dad says is a kind of breakthrough across a boundary of experience between child and parent, but it has another resonance, for the cliff-edge is also related to the experience of those oppressed by the norms of societies that shun difference.

Thinking of the narrowness in some respects of Orcadian culture, Amy remembers from when she was ‘little’ that ‘the only black kid at the secondary school went missing’: he was a boy living ‘near the cliffs of Yesnaby’. Observing the micro-aggressions of adults who see him pass, she allows us to infer the bullying he received at school. And, of course, the cliffs claim him: ‘A week or so later his body was found washed up at the beach. My playground experiences made me assume that racism had driven him to the cliff’. If the stress of oppression can lead to being ‘washed up’, it is a phrase too addicts use of themselves when abandoned by their highs. Amy uses it of her herself when she compares herself to a seal ‘carried by a huge wave’ from the sea onto dry land, behind a high fence; like it ‘I’ve washed up on this island again’.[14]

There are complexities in this too – in Amy’s explanation, for instance, of the assumption she encuntered that, as woman out of control, she deserved the rape she experienced. And, in stating this, we must confront the discussion in her book of addiction narratives and stories of personal recovery (from mental ill health, however caused. One cause is the experience of marginalisation and repression as in misogyny and racism) or addiction that she explores. The point is her account is nuanced by the experience of those people as also on an ‘edge’, one the person telling the story may not wish to renounce or soothe with lithium, as her father was once forced to, until he took personal control: at the end, almost in analogy with Amy he ‘doesn’t take any medication to control his manic depression and has not been seriously ill for years. He has found a way to deal with it himself, … to know the shifts and the lie of the ocean bed’.[15]

THE NATURE OF ADDICTION NARRATIVES OR PERSONAL ACCOUNTS OF RECOVERY

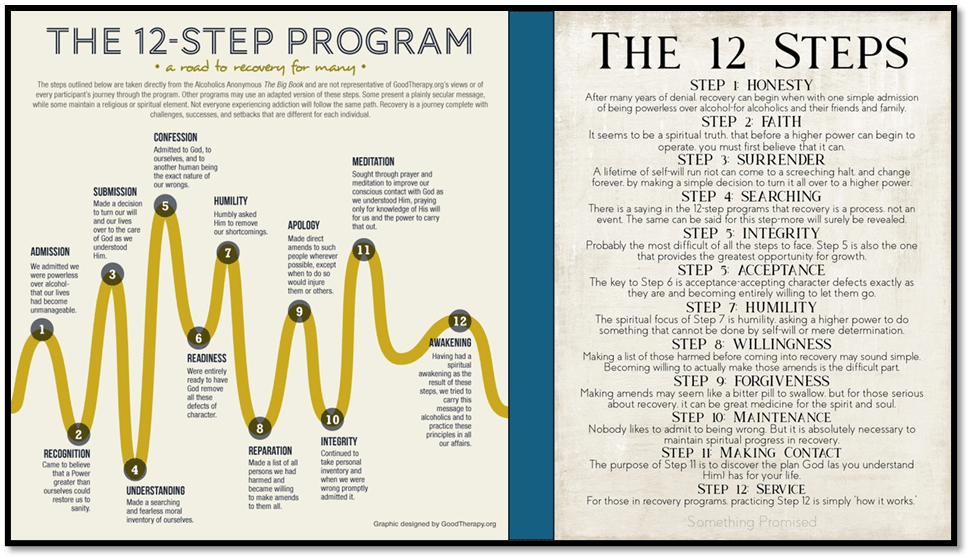

Addiction narratives and closely related personal accounts of recovery can have their own rules of generic construction, provided they are those of survivors. Non-survivor stories nearly always overdo the confidence in the power of the addict to take control of their own addiction, a trait often too near to the denial of there being an issue at all. Addiction narratives are based on an assumption that their narrator is an unreliable one, usually telling stories from the expectation of an ending they expect to have control over but rarely do. It is a characteristic according to Jung of the personalities who might fall to addiction, and in his view, those are narcissistic personalities, locked in their belief that their ego can and will take control eventually. In not being capable of ‘letting go’ of that belief, these storytellers tell of control as an eventual achievable goal that needs no more than the ego to achieve its goals. Jung’s thinking lies behind the Alcoholics Anonymous 12-Steps Model of Recovery.

Amy Liptrot references this programme throughout her narrative, even picking out the steps that usually trouble people who want entire and not limited freedom from dependency on either alcohol, drugs, or other narcissistic highs of ego stimulation. Like them, she ‘had a lot of prejudice against AA’, that, for instance, they would make her ‘relinquish intellectual control’.

For AA, there can only be a decision for total freedom of drugs – abstinence, however, that is attained. Anything else relies again on false beliefs in ego-strength and a failure to be ‘humble’ about that player’s capabilities and surrender to a ‘Higher Power’ outside yourself. These themes control her narrative too, becoming poles that pull it from ‘taking control’ of the direction of the narrative, and sometimes ‘letting go’ of that control in the name of supernature, some principle beyond the conservation of the natural to which she commits. It is the supernatural that allows in the imaginary in that supernature.

But in truth, distinguishing these is difficult. Working with Dee, an addict living on Orkney too, Amy and Dee ‘begin with a study of AA’s Big Book’, but Amy can’t decide ‘whether I’m taking control or letting go’. In AA terms, the two states are similar, even if the focus and agency of control is not God but submission to another Higher Power.à Belief in Higher Power is meeded in AA as a means of taking control away from the narcissistic ego, persuading that bighead to let go of control. It is a beautiful and nuanced thing, cognitively and emotionally.[16]

And this perspective alone can deal with the nuance in what Amy calls ‘cross-addiction’: ‘the idea that, in the absence of drink, alcoholics will transfer their addictive behaviour to something else’, citing food, exercise, shopping, gambling and perhaps even the internet. At its root is not an addictive personality, and here she breaks rank with Jung, but a kind of ‘emptiness’, something like hunger but not; instead a desperate search ‘for what I need to fill me up’, ‘trying to find the right thing to fill this hole’.’ When Amy says shortly after that she is ‘aware of ‘ her ‘addictive and obsessive tendencies’, it isn’t in a spirit of critique of herself or a personality ‘type’ to which she belongs, but to a recognition that a world regulated by the desirous demand of selfish egos alone is insufficient.[17]

Even the excretions of great endangered beasts is of value like the ambergris ‘produced in the stomachs of sperm whales, either vomited or excreted, and found floating on the sea or washed up on the shore’[18]. The major section dealing with this theme is that about the corncrake (or landrail) whose survival experience is studied by Liptrot when later employed by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB).[19] For the corncrake are on the ‘Red List of threatened species of the International Union for Conservation of Nature’, with Orkney populations reduced to ‘thirty-one calling males’ when Liptrot began her study of them, from the volumes islanders remembered in the past when a corncrake call ‘was once the sound of the countryside on summer nights’.[20]

But in nature there is something of the imagined supernatural for her, studying them as she does in the cusps of dusk and dawn, neither day nor night, but a transitional time, making her feel part of a familiar story of supernature, watching valley mists ‘as if I’ve climbed to the top of the beanstalk’. Such moments of something above nature criss-cross her descriptions and fit with the fact that she quotes John Claire in his poem The Landrail, who

describes the phenomenon of birds that can be heard but rarely seen as “like a fancy everywhere / A sort of living doubt”. I begin to doubt my belief in corncrakes.[21]

Like God, anything supernatural appeals not to the senses but a belief in the evidence we hear. That time when she hears corncrakes is replete with Norse supernaturalism – the imagined beauty of old folktales:

This time between sunset and sunrise is known as the ‘simmer dim’ or the ‘grimlins’, from the old Norse word Grimla, which means to ‘twinkle or glimmer’.

Nature stories and writing (and this book won an award for nature writing) can use two genres of writing and their styles – those of science or those of the imaginative evocation or even reference to myth. Liptrot uses all three, allowing them to interact, as in her retelling of her work with the corncrake, but she is at her best in this regard in telling stories of geological deep space and deep time. For life, too, does not stop when we enter the mineral world, for its dying forms are compacted into its soils and further hardened into its mineral deposits, and all play a part in this story.

If mineral erosion (even as a record of extinction of life forms and erasure), for instance, is a fact of nature and geology this does not erase the romance of the stories it tells, in nuanced ways that are both hopeful and sad, as in her narrative of the fate of the Stack o’ Roo, ‘felled by the same processes that shaped it’. ‘Life ‘is getter sadder, but more interesting, she insists’.

Geology has its own hollow ‘emptiness’, ‘tremors’ and collapses as well as beauty. The beauty is SOMETIMES in the very hollow things we explore in this book. Think of the story of Fisherman Douglas, who shows her that the subterranean water caves of the islands are beautiful and networked: ‘The hill is riddled and the ground beneath my feet is hollow’.[22] And knowing that can make you safer than thinking that it isn’t thus. In London, Amy describes the ‘hollow tang of teenage parties’, but in Orkney she learns that she can safely ‘snooze in a sheltered hollow’, that they are useful for ‘storing small boats’ and that ‘trowies are told to live in communities in mounds and hollows of the hills and there are tales of hillyans, little folk who emerge from the rough land …’.[23] Stories of supernature fill holes in reasoned accounts and accustom us to the fact that bad things sometimes happen (both trowies and hillyans bring mischief) for tbey come from the same hollows in our explanatory power and are sometimes beautiful and comforting. Both geology and nature tell us mixed stories after all that sometimes need to evoke supernature.

Liptrot names one chapter (Chapter 22 in fact’ ‘Personal Geology’, and in it she makes the analogy of self, human being, the life of flora and fauna and the mineral and shaped geologies of place and time analogous. If drinking alcohol is part of the a ‘secrets of the night’ , so are the walks and drives of a conservation worker across Orkney.[24] People and geologies have interesting formations that occur around fault lines and ‘damage and erosion’ happen to both in their development in positive and negative ways. Her breakthrough as an addict is also a product of being ‘stirred by the energy of the sea and wind’, in analogy with ‘watching the waves’.[25]

When she discovers a fault line in the form of a ‘rocky ridge’ she also finds that causal accounts of damage are less important than just recognizing that ‘powerlessness and unmanageability’ are both an aspect of geological and personal change.[26] The purpose of the chapter is to ‘study my personal geology’ and people can be so like the geological (Tennyson says so in In Memoriam). A ‘bruxist’ acts like the tectonic plates not because fault lines are immoral but because they exist and always will in faulty interaction with each other. Everything is life, self and others and the built environment is easier accepted and its consequences addressed when they are seen as action of nature, and, if you need that, a higher power but certainly not one in your control.

Imaginative stories too integrate with these narratives, like the story of Captain Ahab in Moby Dick, with whom Amy identifies in her searching for something to fill the holes in her life, which is sometimes why she pursues corncrakes just as she once chased booze: ‘storm-crazed Captain Ahab, but instead of a whale, I’m chasing an elusive bird’. … The corncrake is always just beyond me’.[27] And then there are ‘selkies’. George Mackay Brown once introduced a selkie into a children’s story (‘The Truant’) in his volume Picture In The Cave (I have a beloved signed first edition). Sigurd in it is a dreamer, not an achiever. He has an adventure, though, that changes him ‘in spite of the world’s disapproval’. I think Mackay Brown thought that ‘sea-magic’ made him a poetic storyteller and hate school, but many have since been convinced that he revealed a repressed longing for other boys in his youth. He meets a seal who talks to him, takes him to a magic cave, puts him right about how witches are represented in human stories, and:

Then an astonishing thing happened. As soon as the seal was clear of the water, it reared up and its skin slipped down to the sand. What had been a seal was a white-skinned boy. Sigurd had never seen such an enchanting face and such a lissom beautiful body.. … They laid wondering hands together, and smiled shyly, face into face, for a long time.[28]

Amy Liptrop’s selkies form a similar function. There is a reference to their knack of befriending, even though ‘selkie’ is merely the Orcadian word for ‘seal’. She cites Mackay Brown’s as ‘beautiful naked people ‘ in his novel Beside The Ocean of Time: “And the rocks were strewn with seal skins!” As with geology and nature, Amy borrows the selkie to tell the tale of her journey into a more healthy addiction – walking, and even more swimming, in the sea in the company of Orcadian seals:

By swimming in the sea I cross the normal boundaries. I’m no longer on land but part of the body of water making up all the oceans of the world, which moves, ebbing and flowing under and around me. Naked on the beach, I am a selkie slipped from its skin.[29]

What an addiction story becomes from all these modes of telling it is more than the usual story of ‘recovery’ and ‘survival’. It is about how the emptiness which prompts the imagination is then imaginatively filled with a purpose (environmental conservation in the context of accepted change). The use of fact and fiction in explicating and serving change and the socialising (or rather globalising) of needs is what this book beautifully does. This is not a book about no longer living on the ‘dangerous edge of things’ but of doing it in a way that channels neediness into the cycles of healthy ongoing life, continuous from and outrunning from mere individuals, whose death is acceptable when it comes because earned.

THE PHYSICS AND PSYCHOLOGY OF DURABILITY OR FRAGILITY AS CONCEPTS (INCLUDING CONSERVATION & ENTROPY) & THE EPISTEMOLOGY OF REAL AND / OR IMAGINED ‘WORLDS’.

Amy thinks one night that the ‘animal instinct’, that even took her to the arms of a lover who now despised her in London, was akin to ‘entropy, the concept behind the inevitable decline from order to disorder’, but that so was the way that human trash such as a disposed of ash-tray become half-pebble, and part of the mass of global mineral deposits.[30] She believes then that she has discovered her version of Higher Power in the 12-Steps Programme: ‘the forces I’ve grown up with, strong enough to smash up ships and carve islands’. Entropy is only, after all, a version of creative conservation that accepts the impersonal force of the world, even if it has to be turned into stories of the supernatural.

A person who suffers bodily tremors might understand their neutrality to simple ethics and simpler psychology by understanding the physics of the making of tremors in landscapes or the metaphysics implied in the stories we turn such processes into. In Chapter 2, ‘Tremors’, the experience of ‘tremors or booms’ in the Orkneys, which her father first heard of in supernatural stories of the ‘mythical Mester Muckle Stoorworm’ is detailed: ‘low echoes that seem strong enough to vibrate the whole island while at the same time being quiet enough to make them wonder if they imagined it’. [31] These occurrences have no pattern and the question of their being ‘geographical, man-made, even supernatural’ remains hanging, as does ‘if it happens at all’. Amy discovers its probable aetiology in the play of gales in the hollowness underneath Orcadian surface geology, but can’t be sure. She considers too the story of the Stoorworm and that the Orkney tremors are the ‘aftershocks of the monster’s death-throes’.[32] It is not a long leap from the mythical story of a dying monster that had dragged itself to the ‘edge of the earth’ to expire to the real horrors of global extinction and climatic disruption, because apocalypse needs to be scientifically imaginable if people are to work with it to heal rather than to collude. Likewise, supernature helps us to take in the terrible nuance of nature between its processes of creation and destruction and beautify them, such as the haar in Burray , a fog that ‘turns pink in the sunrise and I can hear seals, across the fields, down on the shore, howling like ghouls’.[33] For ghouls, too, get washed up on the shore of life, and sing in the hollows of the sea caves like selkies.

The imaginary is the manner in which we accept the unacceptable of global forces that are natural. Thus they become explicable, if complexly, but feel like a Higher Power, whose destructive forces we have to respect, as much as its creative power, and art is an amalgam of the knowledge and feel of both. Our notion of a land whose forces are out of conventional order is the stuff of myths, of the Fata Morgana that inverts the visible world, effects of light that queer both space and time shifts, and even a land we have to believe in and work for before it will appear and endure, such as the stories of Hether Blether which show how we might free the land from its spell.[34] Such ways of thinking and feeling are possible in Orkney, less in ‘mainland Britain’, ‘another realm. I’d crossed a boundary not just of sea but also of imagination’. [35] And shifts like this are necessary if we are to genuinely think of changing our ways in ways friendly to the earth we live on; shifts like starting:

… to think in decades and centuries rather than days and months. I think about the people who built the original dykes, … I have flitted and drifted but I want my wall to be permanent. / In the fading light, the farm is timeless, and two huge horses appear, like time travellers, out of the mist.’[36]

Is this fanciful regression or necessary conservation and methodology of sustainable survival. Sometimes we need the ‘enchantment’ of a Hether Blether to know that, one that accepts, if we are to get back we have to know ‘the idea of pollution creating something beautiful’ has to become likable so we know where we are and how we got there, and how it elides with natural phenomena whilst looking supernatural. Imagine taking our eyes away from a computer screen and sleep naturally awaking in the night to see the clarity of planets in apparent still against the motion of clouds. It is ‘a dream : my early-morning sleepwalk among the planets’.[37]

I think this differs from the ordinary recovery narrative because it invokes the necessity of sense perception, reasonable interpretation based on scientific research, and, imaginative action and acknowledgement of the purpose of myth as interactive processes all involved in successful recovery. Such recovery does not demonise the act of needing. It sees it everywhere and elides with natural forces that both destroy and create and work with it. It uses myth to animate the kinds of strength and durabiity required in humans on the edge and does not undermine the value of human desire for more; for that also is an addiction. In London Amy ‘wanted more’: ‘to run the city onto my skin’, ‘inhale the streets’.[38] It is not enough to ‘want nothing more than to stay sober’, [39] you ‘need to do more with’ (yourself) ‘than just not drinking’.[40]

Alone in Rose Cottage, the more she wants is about ‘becoming more interested’ in things outside herself even to the point of addiction.[41] In a small place she learns the need ‘to have more interaction with neighbours’ and knowing people more not because as in London they are ‘more and more like myself’ but accepting difference.[42] In these places, like the Outrun, there is ‘more here than there might seem’.[43] What Amy finds is that attention is key: ‘The more I take the time to look at things, the more rewards and complexity I find’.[44] Overcoming addiction is not about wanting less sensation that seemed to be promised only by the drug, but seeking ‘sensation and’ wanting ‘to be more alive’.[45]

The recovery narrative, as this work sees it, is defined late in the book’s structure. It is not about denying the search to fill a hole but a kind of recycling to increase resources: ‘making use of something once thought worthless’. And if we return to the experience of being ‘washed up’ we do so knowing ‘one can be renewed’. It seems necessary to still seek excitement and employ energy, but it has more use in searching for ‘elusive corncrakes’, and ‘rare cloud’ and the time-space illusions they promote. Perhaps too, it is the payoff from seeking excitement in ‘swimming in cold seas, running naked round stone circles, sailing to abandoned islands, … coming back home’.[46] Remember that Amy Liptrot does not give up living on the edge of things, for: ‘The edge is where I’m from. It’s my home’.[47]

So this is where I end, the night before I see the play at Church Hill Theatre, and probably more than a month until I see the film. The film sounds more conservative as a narrative – contrasting London and Orkney scenes from the one review I’ve read, but much will lie in the performance of it all.[48]

The play, though, will be innovative. I am hungry for it. Dominic Corr unfortunately says it : ‘while ambitious, feels rigid as the stone and granite, rather than a necessary emotional elasticity and enticement”.[49] That challenges me. In contrast, and the reviewer feels more like me than Dominic, Catherine Henry Lamm says: ‘The quality of this production is exceptional in every respect, from sound balance to lighting, subtle but remarkable set design, to the least movement’.[50]

My interest will be in how the features of the book are translated to those of film and theatre. There are obvious differences. The character of Amy becomes the fictional character Rona, played by Saoirse Ronan in the film. In the play we have neither a fictional character nor an attempt at characterising Liptrot herself. Instead we have ‘The Woman’. Is this ‘Everywoman’ of a morality play. It might work if it is, But let’s see.

See you later.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxx.

6 thoughts on “‘The edge is where I’m from. It’s my home’. Preparing to see a performed adaptation of Amy Liptrot’s ‘The Outrun’ by reading the book.”