Yesterday, I was in Edinburgh, and I loved the things I did [see my blog at this link]. However, if I want to give an instance of that nervous exhilaration you might refer to as stand alone and apparently ‘unmotivated’ excitement, it was pushing through the crowds on High Street; stopping behind the backs of others to glance at an act performed from the top of an unsupported ladder, seeing the smiles of people looking free in all of their diversities.

Trips on my own are both exciting and sometimes fearsome when you, for a moment, recognise some kind of paradoxical isolation whilst still being in a crowd. This can be exciting too. In the instance below, it was an anxious moment.

For some reason, whilst walking along a pavement and, in an attempt to keep my balance, I swerved irregularly across the pavement and fell heavily against the soft (thankfully) wall of a construction site. I must have looked drunk because the crowd veered around me, not looking at me and apparently keen on not getting involved. In a rare moment like that, you realise the loneliness of being an unknown factor in the eyes of others, a stranger in a crowd.

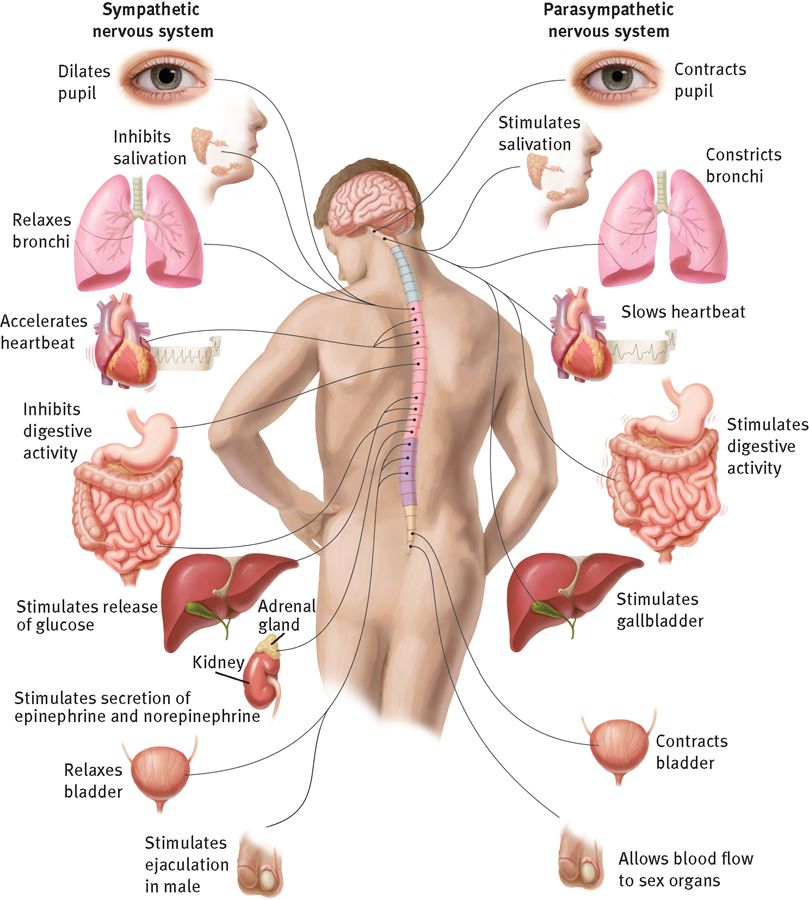

As I think about the closeness of the internal neurological processes of fear, flight, and the frolic of excitement [the processes of autonomic arousal], a memory came to me ratner randomly of watching a film in the exhibition of Norman Cornish and L.S Lowry paintings at the Bowes Museum at Barnard Castle.

That is because Lowry spoke, quite openly and without the self-consciousness, and hint of guilt, usually associated with such ‘confessions’,as being a lonely and rather unhappy man. Asked about his interest in peopled and / or crowded landscapes, he spoke of merely painting what he saw, making clear that what he saw was in fact an interpretation of the outer world in his inner and imagined sight.

My husband has just got me a book on lampposts and lamps in Lowry by Richard Mawson and I am looking forward to reading it, although I have already gathered from it that Mawsin has noticed the ubiquity of lamps as a symbol in Lowry’s art of his feelings of loneliness inside urban spaces.

In the exhibition, I looked for lamps, but they were neither ubiquitous nor obvious most of the time, except for the one drawing below in an unpeopled scene in which a double house front stands by a lamppost, each addressing a kind of emptiness.

That feeling is emphasised by the upward looking perspective as if the viewer were shrunk down into the street by the power of the symbols of emptiness.

Of course, we think of Lowry’s people, industrial and urban landscapes, as populous not lonely. But there are similarities in some, as in, for instance, the scene below where a tenement building looms over the ‘crowd’. The entrance anyway of the gaze of a viewer is obstructed by neglected, broken, but rather frightening, decaying fencework. Trees are winter-naked, and the people are less crowded together than being individuals merely aggregated, with few communicating to each other

Of course, there are exceptions. In the detail below, outside the factory gates, which sill consume the people waiting, we see at least three people conversing together, though at a tangible distance. Nevertheless, the personal space is less protected there, unlike the passing traffic of persons to their left.

Even in a political meeting, there is no apparent togetherness other than of a highly regulated ordered kind. Otherwise, people are a crowd of isolated individuals.

You need, as a result, only a few figures to suggest a populated space.But part of the purpose of these few going about their day is to emphasise that the masses are inside the smoking factories behind them. Yet the mood of the painting is covered by isolated telegraph poles, supposedly connected and networked but standing alone.

Maybe, though people can come together in holidays from work. In the picture below, we see a possible break from work as the means of their sole congregation for one group of people, although the factory still smokes behind the peopled scene. But this is not some kind of holiday. The interactions between children prompt others that involve adults, but largely women and older or disabled adults. I think this piece is still about work. It is the cause in all probability of the disabilities we see in its adults, but their presence possibly also infers that those who can work are further cut off from others in non-functional sociability.

There are smiles on the faces of people otherwise severely disadvantaged, such as the man who wheels himself along on a board, his legs gone. Speaking to a child, he is most happy. Yet there are families here, too. It is a most mixed experience, differing from the scenes above. Does it merely celebrate the excitement of a crowd for various reasons, freed from work slavery. I wonder.

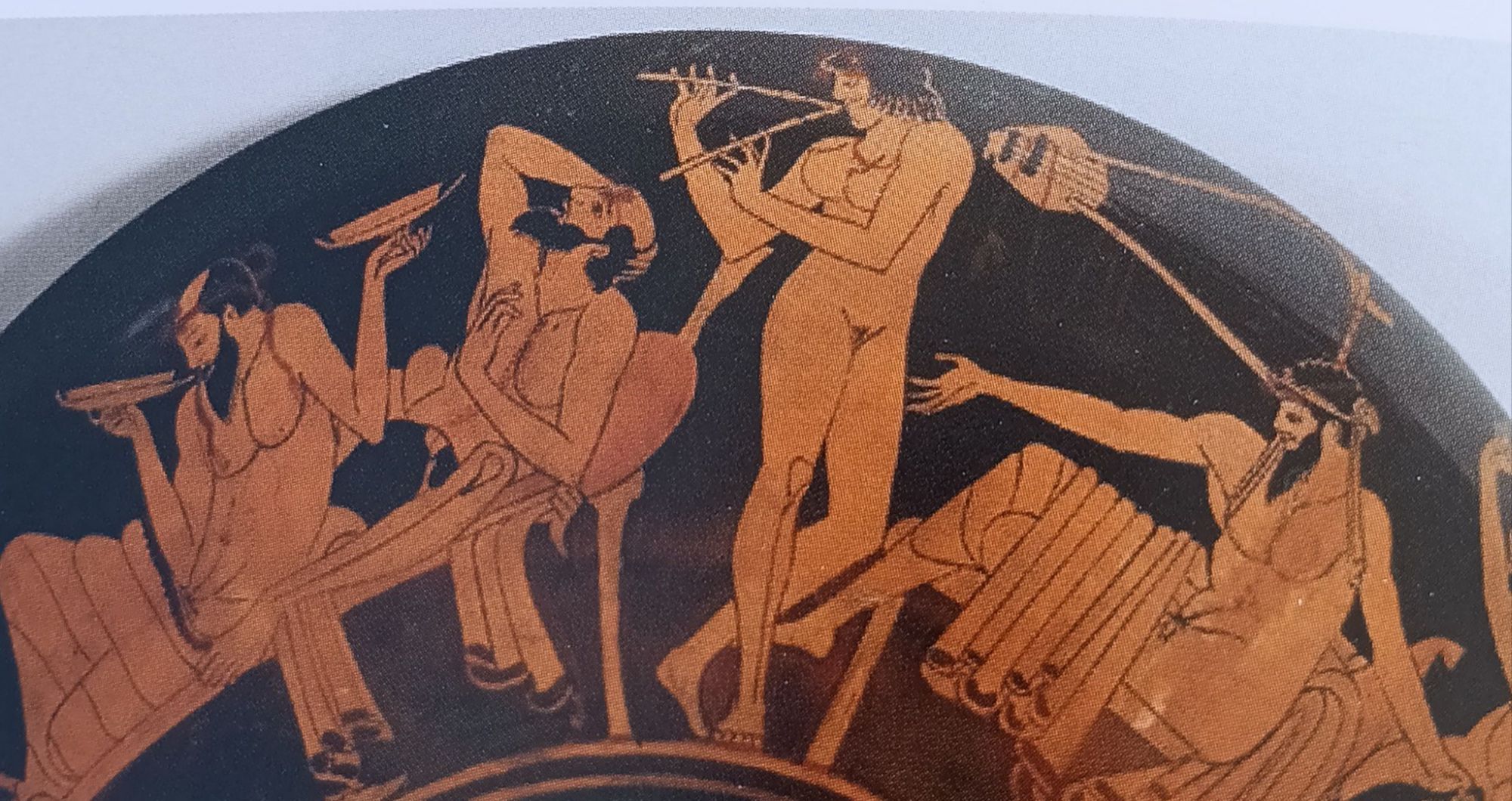

Joy in crowds for the Ancient ‘Classical period’ Greeks was more often joy fuelled by the fact citizens usually had slaves to do the real manual work, and even.provide the entertainment and sexual ex itement, as below. But it is not the excitement of a crowd but a regulated gathering.

Next week I will go to Edinburgh again. I will think about it again.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxx