List 30 things that make you happy.

In Michael Nott’s 2024 biography of the poet Thom Gunn, the man closest to him throughout his life, Mike Kitay, is quoted as saying of Thom first that, ‘He was probably depressed but he would never say that to anyone. He would never act depressed. He would always be cheerful, dancing around the house in his big clompy boots’. Some time later Mike expressed himself more directly about Thom: ‘He needed people to think he was happy, … And mostly he appeared happy, even manic. But sometimes, when no one else was around, he’d lean against the kitchen sink and bow his head and moan, “I’m old!, I’m old!”‘ [1]

There must be many reasons why Thom Gunn, whatever he might also be feeling, thought he needed to know that other people thought him to be happy. The pressure is often heavy or thought to be on males, and queer or gay men in particular, in the light of the pathologisation of the thing that got medicalised by the name ‘homosexuality’. I grew up aware of Gunn but, like him, I felt the pressure to think perform in a way others thought ‘happy’, lest the unhappiness be seen as a symptom of the fact that my attractions romantically were to men and not, romantically or sexually, to women.

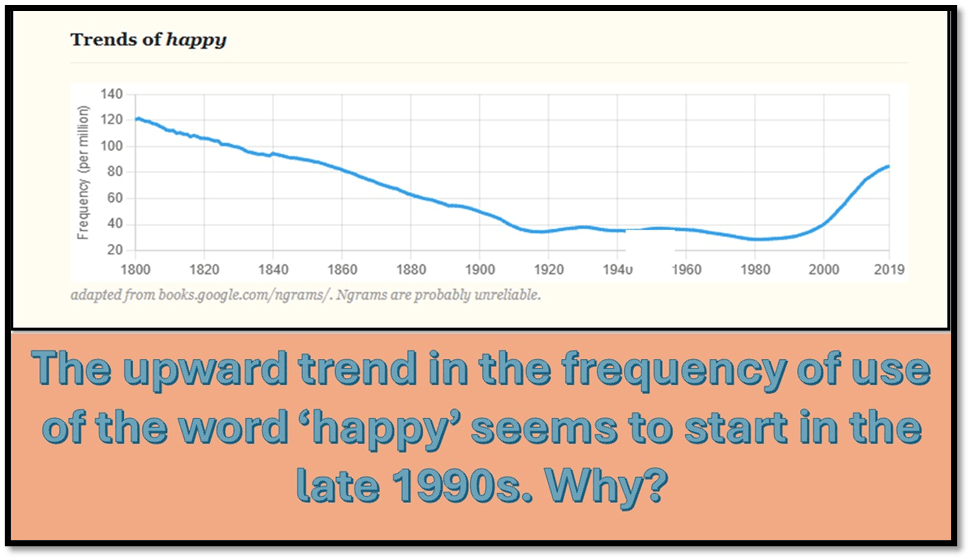

But that is another issue, and one I might take up when I blog later on Nott’s brilliant biography of how queer lives were constructed and reconstructed during the period of Gunn’s life. For now I want just to reflect on the word ‘happy’ and why there is an Anglo-American stress on it that produces prompt questions like this one, which promotes the responsibility of being, and if you can be, looking and acting happy. In the end, performance is all that is expected, although cognitive-behavioural and ‘positive’ psychology argues that if you ‘act happy’, there is no difference in effect, with constant practice thereof, from actually being happy. The word ‘happy’ rises in frequency of use in the 1990s in English corpuses of language use that are examined in Google ngrams. After that, it rises more sharply into the new millennium.

In the 1990s in particular there was an increasing stress on the promotion of positive thinking, feeling and action, in brief a bias towards ‘happiness’ as the only reasonable and healthy response to the world. In social and health care it induced a pressure to ‘enforced cheerfulness’ and government began to be pressured in the USA and the UK to promote ‘happiness’ as policy. Tony Blair’s government in particular was heavily influenced by the thought of Richard Layard, sometimes known as the ‘happiness guru’, who championed the duty of governments to actively promote the happiness of their citizens.

The NHS Plan of 2000 aimed to integrate services, especially at primary care level including early integrated interventions in physical and mental health care seen as a unit, and including young people. Never fully funded, it still implemented the role of Primary Care Mental Health Workers, of whom I was one of the first tranche trained in universities and in primary care in the theory and practice of increasing human well-being through trusted and tried therapies. For Layard, the aim always was the implementation of a plan for happiness not just based on physical and social change – in incomes, housing, or employment, although it included these initiatives. The aim was to increase human demand for happiness over material success as a goal. It was, if you like, the theory behind our prompt question – although now handed over to the private sector and informal structures for increasing well-being. Government took a back-step after later, right-wing, governments began to boast that the happiness of the many was no concern of theirs, ‘happiness’ being a private thing..

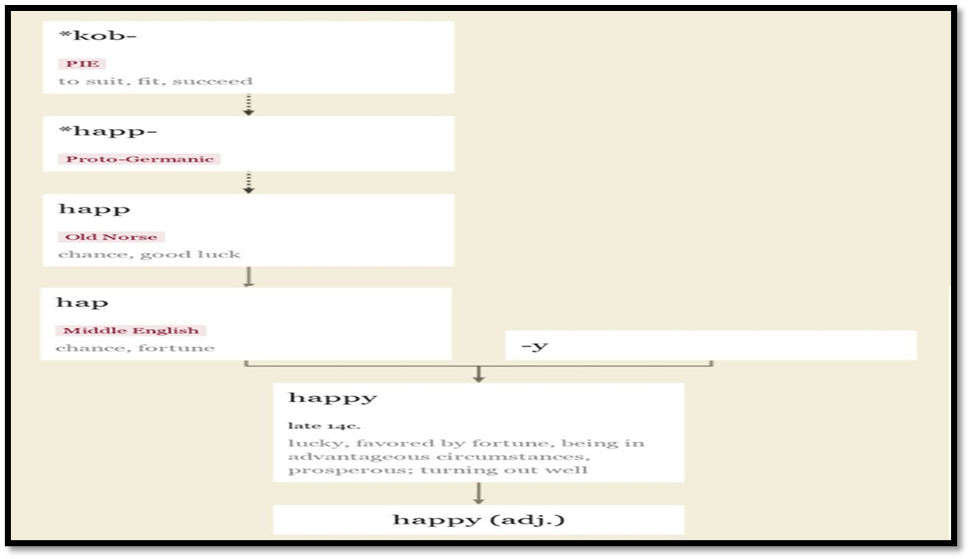

But I think there is a problem in the state pursuit of happiness or its triggers, whether a list of thirty or less. The word happy has an interesting etymology, reproduced below from etymonline.com.

The text from the same source is as follows, attributing the English etymology to borrowinngs from other languages and only adding the fact that ‘haps’ meant good things, things that make you ‘happy’ in the late 14th century (1300s) and only surely so in the sixteenth century (1500s). The old English term was the root of our modern archaism, ‘blithe’ – from bliðe – as in Shelley‘s poem “To a Skylark“, (“Hail to thee, blithe Spirit! / Bird thou never wert“).

Late 14c., “lucky, favored by fortune, being in advantageous circumstances, prosperous;” of events, “turning out well,” from hap (n.) “chance, fortune” + -y. Sense of “very glad” first recorded late 14c. Meaning “greatly pleased and content” is from 1520s. Old English had eadig (from ead “wealth, riches”) and gesælig, which has become silly. Old English bliðe “happy” survives as blithe. From Greek to Irish, a great majority of the European words for “happy” at first meant “lucky.” An exception is Welsh, where the word used first meant “wise.”

However, I sense an earlier history is important since the root ‘hap’ is also fundamental to the word, happen, happening and mishap. The late fourteenth century etymology forces this root to associate with ‘good fortune’ or ‘positive event’, yet examples of hap from the thirteenth century stress chance, fortune, fate, do not imply that these things are necessarily and always positive in effective – here again Etymonline.come on hap from the word mishap.

c. 1200, “chance, a person’s luck, fortune, fate;” also “unforeseen occurrence,” from Old Norse happ “chance, good luck,” from Proto-Germanic *hap- (source of Old English gehæp “convenient, fit”), from PIE *kob- “to suit, fit, succeed” (source also of Sanskrit kob “good omen; congratulations, good wishes,” Old Irish cob “victory,” Norwegian heppa “lucky, favorable, propitious,” Old Church Slavonic kobu “fate, foreboding, omen”). Meaning “good fortune” in English is from early 13c. Old Norse seems to have had the word only in positive senses.

Of course somehow human beings like to stress events that turn out well, but a positive ‘hap’ does not exclude that possibility that some ‘haps’ are ‘mishaps’, examples of bad or poor or unlucky fortune. The word ‘happenstance’ does not imply that accidental events that turn up in our life are always good ones for our fate is nuanced by varying events, sometimes with mixed advantages and disadvantages. Yet it appears to be the Vikings that forced the positive association.

So I cannot name 30 ‘haps’ that make me ‘happy’, only things that have an effect on my fortune colouring it one way or another and sometimes in a mixed ways’ Hence I answer this prompt in verse, My 30 ‘haps’ (unforeseen occurrences)” being only and precisely that: 30 ‘haps’, their value yet unassessed but changing me..

I’ll try my luck and test my fate, in maps Drawing the chance events I will attempt: Haps, haps, haps, haps, haps, haps, haps, haps, and haps Name nine of them, one more hap will exempt Me from a longer line but requires more Haps, haps, haps, haps, haps, haps, haps, haps, and haps. One more hap will add to my mounting score Making twenty. Yet to thirty I’ll soar: Haps, haps, haps, haps, haps, haps, haps, haps, and haps, One hap lacking , adding now. The crowds roar ‘He is happy now!’ – ‘No! Changed perhaps’.

Make your experience add up to too, but don’t expect it all to be positive. For that’s the way to a poor lived life, restricted in events. Believe me!

With love

Steven

_______________________________________________

[1] Michael Nott (2024: 513) Thom Gunn: A

One thought on “In Michael Nott’s 2024 biography of the poet Thom Gunn, the man closest to him throughout his life is quoted as saying of Thom, “He needed people to think he was happy. … But sometimes, when no one else was around, ….”.”