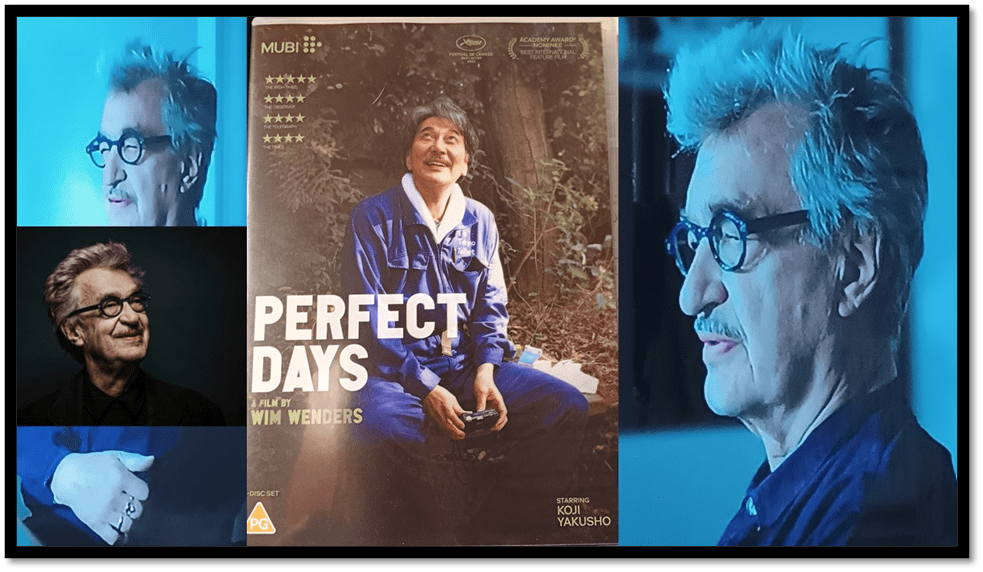

In interview available in the DVD version of this film, Wim Wenders says that ‘Too much story is a disaster’. That is because, as he suggests in an interview available with the recently published DVD, too obvious manipulation of plot interferes with the process of an audience being able to ‘enter into’ the filmic artists ‘propensity of seeing’. Wenders insists at the same time that art is about seeing ‘with a different kind of attention’ whether by the painter in visual art, by poets in words or by the filmic artist in the shared seeing and feeling of the dynamic interaction between images, sounds, words and rhythmic motion in movies. This blog is an attempt to understand what he might mean in relation to the film Perfect Days (2023), collaboratively produced with co-scripted by him and writer-director Takuma Takasaki and starring the wondrous Koji Yakusho.

For E.M Forster it was a obviousness that perhaps still surprised him, given the cultural weight he ascribed to art that was still a bit surprising:

There is a similar ambivalence if more weighted into an attack on the too obvious driving mechanism that a story can be in Wim Wenders discussion of his art in the film Perfect Days in the MUBI video version of the film ‘extras’. Wenders is insistent but not always able to clearly articulate, for it is a point intrinsically obscure, the double truth that though a film requires the framework of a story, the story should not appear to drive a film’s unfolding, or the unfolding of its characters’, or impose itself on the feeling an audience has that it is merely observing and ‘following’ the life of a person or group as in a documentary.

We know, of course, that a script pre-existed the film, and indeed, Wenders tell us that. Hence a manipulated story was there already – that much, we have to agree with Forster, is a sad necessity. We know, for instance, from this interview that before the film, Wenders imagined a backstory of the hero as an alcoholic businessman deeply unhappy with his life and interactions, even with his family, and that he did not cope with his father’s dementia. Wenders even imagined a past breakdown and suicide attempt, which led to the new life Hirayama lives now as a way out of his existential crisis. We know even, before the film went into production, that he imagined the main character as a secular ‘monk’, modelling him on Leonard Cohen.

However, Wenders insists that in direction of the film afterwards, the role henceforth of the producer-writer-directors was to make the events look as if they were mere accidents in the progression of a life otherwise running naturally along a river bed, or at least a road not obviously constructed for the purposes of knowing the character. And the run of roads and rivers are wondrously observed in this film, as it documents the Tokyo of its personae, as we shall see.

A story element that is too obvious, he goes on to say in the interview, is like an ‘elephant’ sitting in a room, put there by a storyteller whose manipulation of things is too obvious. The elephant embarrass an aware audience just as it does Wenders he thinks. At the least, story elements should be not gross like an elephant but compact of spirit and small, like an ‘elf’, as Wenders says it. Hence he insists he allowed Yakusho to improvise his character, adding elements that were merely filmed as if following a ‘real’ person in a documentary, even tricks relating to the cleaning of toilets. Only other characters being in a scene demanded ‘rehearsal’.

However clearly there were pointers in the script to this very relaxed view of narrative development as if like that of ‘natural’ events. A favourite scene of mine relates to Hirayama cycling through Tokyo with Niko. As they cross a bridge, Niko asks if the river below runs to the ocean and whether they could go and see. ‘Next time’ says Hirayama. But when is ‘next time’, the impetuous youth demands. There is no commitment in the answer, only a belief that things happen when it is natural they should and that to be in the ‘now’ is what matters:

The next time is the next time.

Now is now.

The pair ride off down the wide cycle path zigzagging across and repeating that mantra with joy.

A film succeeds Wenders thinks only when the filmmaker makes life appear as it does through the eyes and with the feeling of their shoes on your feet of a character who you assume to be real and to whom things happen in the course of an otherwise nearly predictable routine of life through its daily cycles. The Observer’s Wendy Ide noticed in the cinema without help from this Wenders interview, that this mastery owed much to a model in Japanese film-making. She says: ‘With its gentle rhythms, leisurely pacing and quiet profundity, this Tokyo toilet story has an obvious debt to the work of Yasujirō Ozu’.[1] According to Wenders, Yasujirō Ozu was a model precisely because of his ‘heightened attention’ to ‘things and scenes’. Within the Ide quotation above too we see that there is a wonder bound up in that this fact of attention to things rarely attended to in a heightened way is revealed for the source of the story’s routine framework is the cleaning of Tokyo’s public toilets. That Japanese public toilets command attention in their technologies and architecture though is a complicating factor in comparison to the lack of public pride in such institutions in the UK.

The main character, played by Koji Yakusho, Hirayama, is a toilet cleaner and we see him cleaning a series of the same toilets daily. The source of routine for his fictional character concerned Wenders too: ‘Who wants to see another person clean a toilet?’, he asks. And then says why that you could only want to do so in relation to the ‘attention’ the character gave to that task in order to feel what it was like to give such an unusual level of attention to a mundane task we prefer not to think about. For that reason we can bear even to see the very same toilet we saw cleaned before cleaned again but with a difference precisely, in order to keep us interested, in the level of attention.

This refocusing of an audience’s attention is achieved Wenders argues by the use of the narrative device available to film of ‘reverse angle’, wherein the camera cuts from the shot of the person, sometimes a close-up of their eyes indeed, to ‘see’ what their eyes are ‘seeing’. This is more obviously done, and is easier to talk about, in his attention to trees, whom his niece Niko believes might be his friends.(Wenders says it is also an ‘act saying thank you for the light’.) Niko may get that slightly askew. Are they friends or family (perception of them certainly fuses with both friends and family in his monochrome dreams)? Wenders further insists that a story that is elfin rather than elephantine in its story elements is like a family member turning up in your life without notice, as does his sister’s daughter, Niko, an event that draws in the most prominent and elephantine of characters, his sister.

She enters with a huge chauffeured car and from, in her words as reported by Niko, ‘another world’ of riches, privilege and stress. This sister says the words we were thinking but dare not say: ‘So you spend your life cleaning toilets’, and revealing that once Hirayama was part of a very different world living a very different life. So why should trees not be family. Why should you not foster heir seedlings as bonsai miniatures, in reverence but also in changing your relationship to them to something more permanently curatorial and perhaps possessively so. For if huge trees dominate you in mediating spreading light through their leaves, cannot you foster that dependence on them in bonsai form.

In my last observation about Hirayama, I sense that I see him differently from the newspaper critics and others I read, and perhaps from Wenders too. Wendy Ide sees him very differently, and much more simply, however and I cannot entirely justify my reading against hers, except that I feel there must be something more than a lesson in zen Buddhism and mindfulness of attention in Hirayama. Is it, as I sometimes think, a sense that the giving of lessons in attention is sometimes the imposing of attention, a kind of power that may not only be for good. Ide writes thus (I connect two of her ideas here by omitting some material):

There is a Japanese word, “komorebi”, which was the original title of the film. Literally translated, it means “sunlight leaking through trees”, but there’s more to it than that. It speaks of a profound connection with nature, and the necessity to pause, to take the time to absorb and appreciate the perfection of tiny, seemingly insignificant details. Hirayama has not only grasped all of this, he has made it the keystone of his essence. He sees all things, all people, as equally important, with an equal capacity for transcendence. …

Hirayama’s ascetic existence is stripped back to basics: …; a point-and-shoot film camera with which he captures the things that please him; the interplay between the sky and the trees. Trees, it seems, have a particular significance for Hirayama, something that he pays back by carefully rescuing fragile Japanese maple seedlings in order to nurture them in his apartment.

Nurturing is never anything other than complex,I believe, and in this I perhaps am more cynical than Ide. The claim to nurture is sometimes also a claim to power over the nurtured, and sometimes transposes care and control in the interest of ideologies like that of ‘giving care’ in ways that might control, although perhaps best if that is only in the control of tree growth through the methods of bonsai. If trees are Hirayama’s family, it might be useful to remember another pregnant phrase in the interview with Wenders I have been referring to: “Family is also a fiction”. And family changes according to the attention we give to each of its members, whether we are within that family or not.

I think that how you respond to the film’s demand to attend to the smallest things that might appear in it however is vital to whether you like the film or not and how much of either like or dislike it creates. It does create a world in Hirayama’s viewpoint that is purposely shut off from taint by others whilst it relishes them, finds beauty in them and helps them find beauty in themselves. Hirayama needs nobody, and once he has offered his vision of things to others, he can dispense with further responsibility or ongoing care of them as he does his father, or, like his Bonsai seedlings, effectively mentally miniaturise them in order to represent his joy in them without their being intrusive beyond the rituals of original care required. It means that he is unquestionably a good man, of course. For instance, he teaches a man who has terminal cancer to find joy, for instance, in interactions with others and their shadows in the environment through a game of tig with shadows, in which he differentiates how and why individuals cast them with apparent difference of ‘density’ or darkness.

Likewise, he shows his niece, Niko, that she can and must put up with her overbearing mother until she is old enough to live alone and make her own decisions. Yet, it is he, after all, who telephones his sister to allow her to pick her daughter up. It is the sister who reminds Hirayama that he has abandoned his father with Alzheimer’s and will not see him. And we know that he is unlikely to see the man with cancer again.

Hirayama is a complex man, fiction though he be. I see the purposeful shutting off from the world in the architecture Hirayama chooses for his abode as a kind of cloistered space behind and to the back of other houses, with an automatic coffee can dispensing machine we only see him ever using. It reeks of Mariana in the ‘moated grange’ on a superficial gaze:

The broken sheds look'd sad and strange:

Unlifted was the clinking latch; [2]

However Hirayama is no inclined to look at such evidence as justification for a ‘dreary’ life however unvisited or unattended to he may be, for his own attention to others is his secret. Nevertheless, the lighting and dilapidation might evocation dreariness from another even without the early morning routine of cleaning up in service to others:

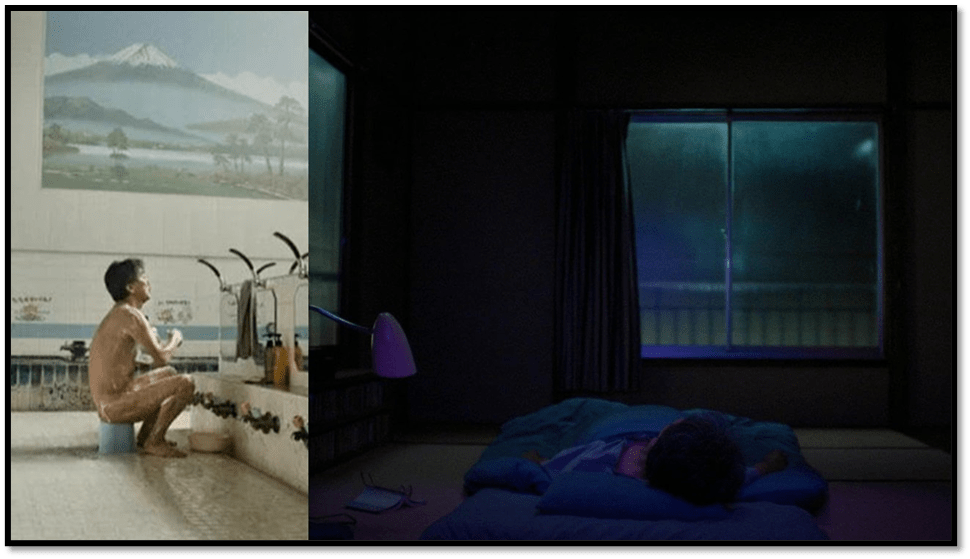

Unlike Mariana though, Hirayama embraces being alone. Though constantly noticing and attending to everything and everyone around him, the return of any attention from things and persons seems accidental or bound up with his habitual routine, such as the acquaintances in a cafe who might talk but not specifically to him. Early in the film he hears a young boy child crying for his mother; unable to get out of the toilet into which he had wandered when, presumably, his mother’s attention had wandered. He seeks to help the child only interrupted when the mother returns, calls the child away, chastising the child for what, after all, was her inattention, and. as as she does, walking away, barely looking at Hirayama and certainly not thanking him, perhaps even blaming him for crimes she imagines out of her guilt. In the bath-house he attends (left in the collage below) he sits alone, others laughing if with a friend (there are two charming older gentleman entering the cold dip pool on the last occasion we see, they ignore him. This is the way of the city.

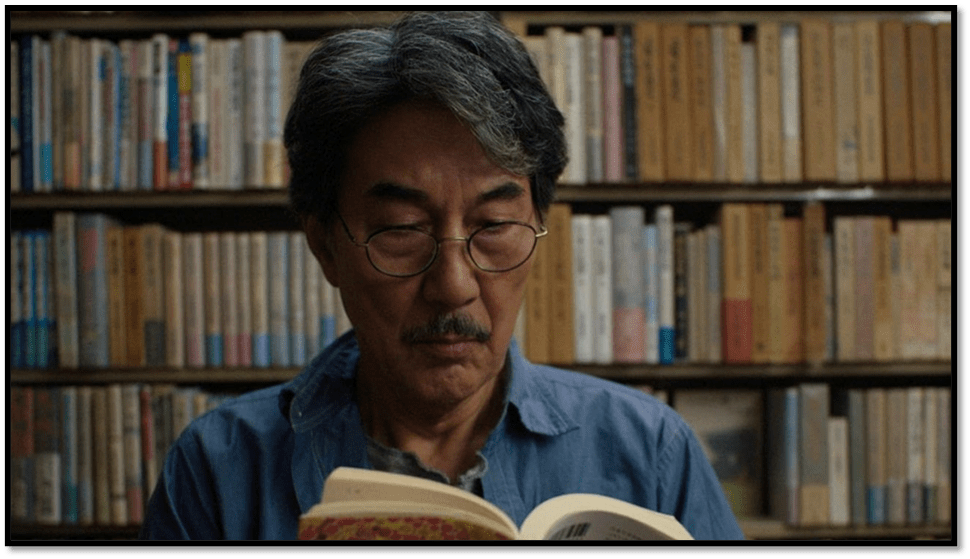

While other pedestrians ignore the vagrant who camps in a park, Hirayama watches in wonder as the man moves in his own dance of self-expression. And the toilets themselves, although humble in purpose, are architectural gems, as we have seen above. Once locked in his den home, Hirayama is alone with his routine – spraying his bonsai gently with water and reading where the light from his angle poise is good enough, his book then put aside next to his foldable futon mattress (which becomes a box seat in the corner of his small living and bedroom) – right below. He does not display boredom yet the blue colouring of the available light from street-lighting through his windows has a melancholy and somewhat ghostly feel.

Peter Bradshaw, with his usual brandishing of insensitivity as a critic, if it were the norm for that activity, ‘found something a little too subdued in this film’ , resting its success in ‘urban charm’ and in the splendid performance of Yakusho. Indeed he says in opening his critique, rather waspishly given the generally sloppiness of his response, that it is entirely:

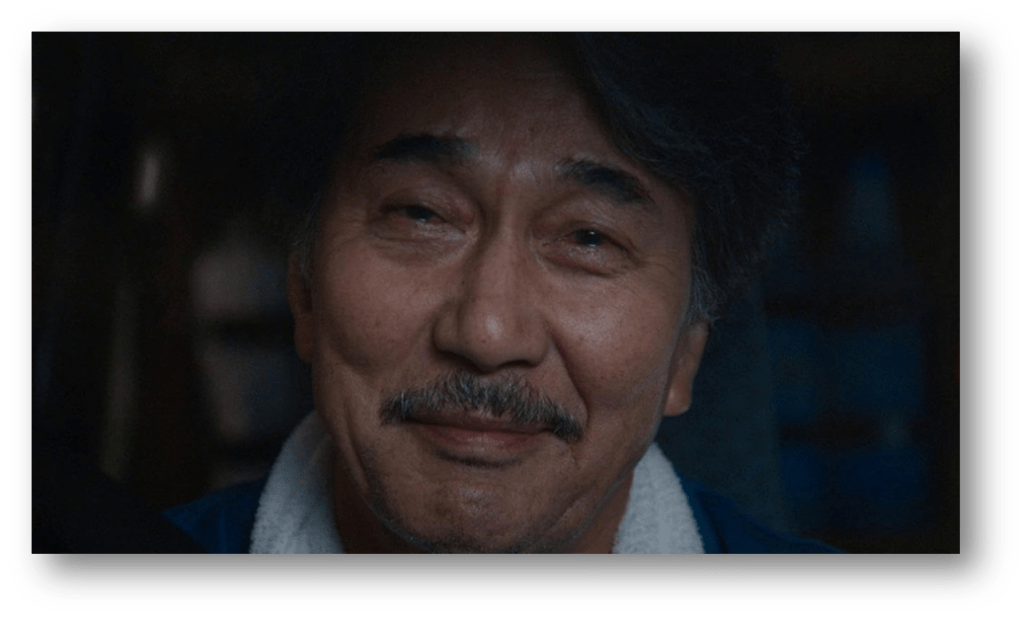

… a bittersweet quirky-Zen character study set in Tokyo which only comes fully to life in the final extended shot of the hero’s face, drifting back and forth between happiness and sadness. There are some lovely magic-hour scenes from cinematographer Franz Lustig, shooting in the boxy “Academy” frame.[3]

There is, by the way, a good explanation of the ‘Academy ratio’ in framing film by the BFI, which shows that Bradshaw is using appropriate critical language here (use this link). However, had I deliberately sought more words to diminish the achievement of a filmmaker while apparently praising lots going on in his work, I could not have done so as well as in these sentences. Bradshaw is correct in saying that that last long and lingering shot of Yakusho is wonderful, however.

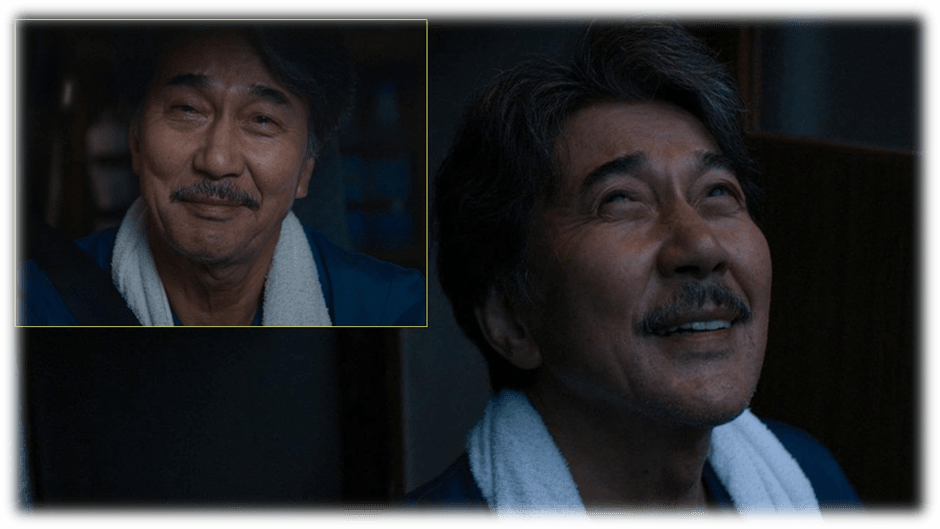

As we watch that sequence, at any moment, the actor’s face can be on the cusp of despair, actively melancholic or cheerfully breaking into the most beautiful of smiles that engages with something inwardly as if it were doing so outwardly in the public world – the way he actually does in the outside world with things, like the dawn, and people if anyone is attentive enough to him, which we feel the trees are. At the very end of the film, it is a sign that those who have learned how to attend to detail as Hirayama does, will be rewarded with the complexity in appearances that penetrates under surfaces and within the interior spaces of thought and feeling for find those complex cycles of intersecting feeling about the world that makes its contemplation significant. Below is one of the moments of transition worthy of study and full attention.

But it is nonsense to say the film only comes alive in this last long shot, for the meanings that play through the contemplation of that face itself contemplating an inner invisible world that interpenetrates the city we know he is also seeing outside his van window can only be as richly meaningful as it is because we have seen how it comes about through watching the film thus far. That close watching includes the ritual facial expression offered to the morning or in the attention given by a surprise, like a visit, t that surprise of seeing a thing in a new and different way from that which was familiar to him, like the trees, the river, and the beauty of the built city.

Hirayama teaches us to attend by the direction of the gaze and the responsiveness of faces that can mirror each other, as with Niko below (the inse picture I put there to show this process is still going on when the character is alone and he becomes an object to himself within his contemplative framework).

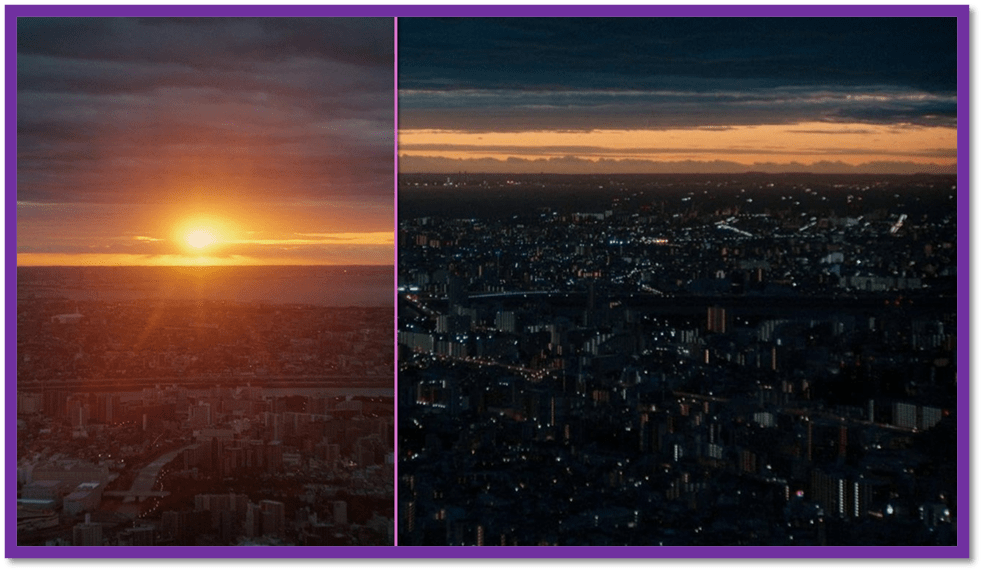

Surely the same is true of the brilliant cinematography, which is often offering a ‘reverse angle’ shot but from the perspective of a literally heightened imagined perspective we’ll above the city, perhaps from the Skytree Tower, which is such a feature for everyone in the film. Reverse angle your imagination from the building below then:

Imagine that and you get something like the beauty of the morning (left) and evening (right) shots over the city below in the collage – abstracted from the film where they are so much better objects of attention to light and reflection.

To see that last shot, as we should see it, we require the training of the attention and knowledge of the contents attended to during that training. Part of the education is to see that Hirayama actually often sees things, people, and the meaning of relationships with and through his heart as he does the deeds that make him engage with these when asked. Take the beautiful shot below, where he has lent his assistant, Takashi (Tokio Emoto) both money and his van.

The latter drives with his hoped-for girlfriend (the one blonded with her nose in her phone) next to them and with Hirayama in- between, gazing at both and ahead while they talk about his taciturn nature, and the oddness of his working life. Takashi says Hirayama is good but odd in that he has set himself with a repertoire of his own equipment including the van for the same pittance as other toilet-cleaner team leads have. These questions matter in one way and not in another. What does matter is that we learn that Hirayama has invested in his simple life of service from supposed riches from his past. We learn all this from attending to the dramatic play of eyes between the three which happens simultaneously. He is is imagining their inner lives and everyone knows that. So thoroughly does he enter the imagination of others that his presence acts like an epiphany on the girlfriend, who returns a tape Takashi put in her bag to him (who had not realised it ‘lost’) and kisses him in thanks for being different to other men.

The classic act of noticing in the film by Hirayama is of the man called simply in the film ‘Homeless’ (played by Min Tanaka) whose graceful motions in honour of something or nothing Wenders elaborate in a short film featuring the same actor in monochrome on the extras disc of the DVD version. Its name is Some Body Comes Into The Light. It is beautiful to watch in quite unconventional ways, for it does not rely on the beauty of the dancer’s face or body but in the pattern of movements made against light and shade, and in honour of the trees.

Min Tanaka in ‘Some Body Comes Into The Light’ (left) and (right) dancing in the city

Meanwhile, when attending to people, relationships, and objects, he attends to second-hand books he reads and collects in his room recommended by a lonely bookseller.

In his car and home, he listens to music. Wendy Ide describes the music thus:

Equally important in our understanding of Hirayama’s journey through the world is the choice of music. He listens to 60s and 70s American and British rock – the Velvet Underground, the Kinks, Otis Redding, Patti Smith – and Japanese folk from the same period. The song choices – in particular the Lou Reed track that gives the film its title and Nina Simone’s Feeling Good – are windows into his soul at any given moment. Hirayama has found harmony, although there are suggestions of a previous, more privileged life, in which this was not the case. This sense of peace and equanimity is a rare thing in the central character of a film – cinema, after all, thrives on conflict and discord. They don’t call it drama for nothing.

The soundtrack is not only right, its instruments being supposedly obsolete audio tapes have a role in the drama. Having ‘come back into fashion’ Takashi thinks he might up the quality of his love life if Hirayama sold the tapes, for 120 yen, and lent (effectively gave in fact) the money to him. Lou Reed is especially lucrative. This transaction does not have value to Hirayama, hence he keeps the tapes and gives enough money to Takashi anyway to allow him to seek another job and leave Hirayama in the lurch with a double shift of cleaning to do next day, although claiming he will eventually pay back the money.

One piece of music not spoken about by Bradshaw nor Ide is a rendition of a version of The Animal’s The House of the Rising Sun. It is adapted and sung by a middle-aged female coffee bar owner, divorced from the man Hirayama later befriends and who is dying of cancer mentioned above. She sings the song in words in the role of one of the women sex workers from the brothel rather than a male client of it as in the original. It builds a bond among the lonely older men in the café, a kind of melancholy brotherhood open to the sadness of the world as well as joy. It is so profoundly attended to in the story that it seems a kind of miracle of genre-bending.

Of course, it is clear that I can not recommend this film enough, though one thing worries me. If Wendy Ide and others are right about the film as being entirely positive about the way it insists, according to them, on life being good if only we see it differently enough, then it joins a tradition of art that includes pastoral narrative, which pretends that life is complex and stressful only for the rich and powerful and they alone have complex responsibility but not so for the lower classes employed by others in ‘simple’ tasks, like tending sheep or cleaning toilets. This is so far from a fundamental truth, of course, that I redeem my liking for the film only by thinking to myself that we do not have to be entirely positive about Hirayama’s redemption through Zen mindfulness, or positive psychology. In fact, Hirayama’s life is really simplified by the capital he brings with him from another life which enabled him to buy the resources which make his toilet cleaning so especially attentive, a van full of appliances as noted by Takashi.

But do see it. I find it wonderful and very beautiful.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxx

[1] Wendy Ide (2023 ) ‘Perfect Days review – Wim Wenders’s zen Japanese drama is his best feature film in years’ in The Observer (Sun 25 Feb 2024 08.00 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2024/feb/25/perfect-days-review-wim-wenders-koji-yakusho-tokyo-toilet-cleaner

[2] Tennyson ‘Mariana’ at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45365/mariana

[3] Peter Bradshaw (2023) ‘Review: Perfect Days review – Wim Wenders explores a quiet life in Tokyo’ In The Guardian (Thu 25 May 2023 17.03 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2023/may/25/perfect-days-review-wim-wenders-tokyo-toilet-cleaner

One thought on “This blog is an attempt to understand why Wim Wenders thinks ‘Too much story is a disaster’ in speaking of his film ‘Perfect Days’ (2023), starring the wondrous Koji Yakusho.”